Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), describes a technique widely used in biochemistry, forensics, genetics, molecular biology and biotechnology to separate biological macromolecules, usually proteins or nucleic acids, according to their electrophoretic mobility. Mobility is a function of the length, conformation and charge of the molecule.

As with all forms of gel electrophoresis, molecules may be run in their native state, preserving the molecules' higher-order structure, or a chemical denaturant may be added to remove this structure and turn the molecule into an unstructured linear chain whose mobility depends only on its length and mass-to-charge ratio. For nucleic acids, urea is the most commonly used denaturant. For proteins, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is an anionic detergent applied to protein samples to linearize proteins and to impart a negative charge to linearized proteins. This procedure is called SDS-PAGE. In most proteins, the binding of SDS to the polypeptide chain imparts an even distribution of charge per unit mass, thereby resulting in a fractionation by approximate size during electrophoresis. Proteins that have a greater hydrophobic content, for instance many membrane proteins, and those that interact with surfactants in their native environment, are intrinsically harder to treat accurately using this method, due to the greater variability in the ratio of bound SDS.[1]

Procedure

Sample preparation

Samples may be any material containing proteins or nucleic acids. These may be biologically derived, for example from prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells, tissues, viruses, environmental samples, or purified proteins. In the case of solid tissues or cells, these are often first broken down mechanically using a blender (for larger sample volumes), using a homogenizer (smaller volumes), by sonicator or by using cycling of high pressure, and a combination of biochemical and mechanical techniques – including various types of filtration and centrifugation – may be used to separate different cell compartments and organelles prior to electrophoresis. Synthetic biomolecules such as oligonucleotides may also be used as analytes.

The sample to analyze is optionally mixed with a chemical denaturant if so desired, usually SDS for proteins or urea for nucleic acids. SDS is an anionic detergent that denatures secondary and non–disulfide–linked tertiary structures, and additionally applies a negative charge to each protein in proportion to its mass. Urea breaks the hydrogen bonds between the base pairs of the nucleic acid, causing the constituent strands to separate. Heating the samples to at least 60 °C further promotes denaturation.[2][3][4][5]

In addition to SDS, proteins may optionally be briefly heated to near boiling in the presence of a reducing agent, such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or 2-mercaptoethanol (beta-mercaptoethanol/BME), which further denatures the proteins by reducing disulfide linkages, thus overcoming some forms of tertiary protein folding, and breaking up quaternary protein structure (oligomeric subunits). This is known as reducing SDS-PAGE.

A tracking dye may be added to the solution. This typically has a higher electrophoretic mobility than the analytes to allow the experimenter to track the progress of the solution through the gel during the electrophoretic run.

Preparing acrylamide gels

The gels typically consist of acrylamide, bisacrylamide, the optional denaturant (SDS or urea), and a buffer with an adjusted pH. The solution may be degassed under a vacuum to prevent the formation of air bubbles during polymerization. Alternatively, butanol may be added to the resolving gel (for proteins) after it is poured, as butanol removes bubbles and makes the surface smooth. [6] A source of free radicals and a stabilizer, such as ammonium persulfate and TEMED are added to initiate polymerization.[7] The polymerization reaction creates a gel because of the added bisacrylamide, which can form cross-links between two acrylamide molecules. The ratio of bisacrylamide to acrylamide can be varied for special purposes, but is generally about 1 part in 35. The acrylamide concentration of the gel can also be varied, generally in the range from 5% to 25%. Lower percentage gels are better for resolving very high molecular weight molecules, while much higher percentages are needed to resolve smaller proteins.

Gels are usually polymerized between two glass plates in a gel caster, with a comb inserted at the top to create the sample wells. After the gel is polymerized the comb can be removed and the gel is ready for electrophoresis.

Electrophoresis

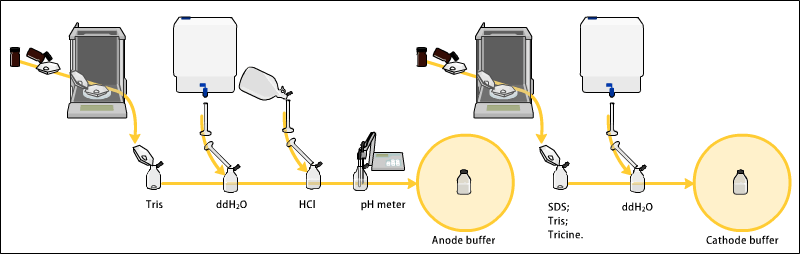

Various buffer systems are used in PAGE depending on the nature of the sample and the experimental objective. The buffers used at the anode and cathode may be the same or different.[8][9] [10]

An electric field is applied across the gel, causing the negatively charged proteins or nucleic acids to migrate across the gel away from the negative electrode (which is the cathode being that this is an electrolytic rather than galvanic cell) and towards the positive electrode (the anode). Depending on their size, each biomolecule moves differently through the gel matrix: small molecules more easily fit through the pores in the gel, while larger ones have more difficulty. The gel is run usually for a few hours, though this depends on the voltage applied across the gel; migration occurs more quickly at higher voltages, but these results are typically less accurate than at those at lower voltages. After the set amount of time, the biomolecules have migrated different distances based on their size. Smaller biomolecules travel farther down the gel, while larger ones remain closer to the point of origin. Biomolecules may therefore be separated roughly according to size, which depends mainly on molecular weight under denaturing conditions, but also depends on higher-order conformation under native conditions. However, certain glycoproteins behave anomalously on SDS gels.

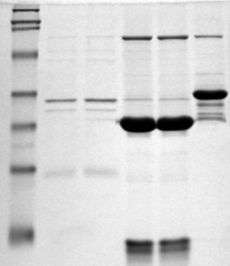

Further processing

Following electrophoresis, the gel may be stained (for proteins, most commonly with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250; for nucleic acids, ethidium bromide; or for either, silver stain), allowing visualization of the separated proteins, or processed further (e.g. Western blot). After staining, different species biomolecules appear as distinct bands within the gel. It is common to run molecular weight size markers of known molecular weight in a separate lane in the gel to calibrate the gel and determine the approximate molecular mass of unknown biomolecules by comparing the distance traveled relative to the marker.

For proteins, SDS-PAGE is usually the first choice as an assay of purity due to its reliability and ease. The presence of SDS and the denaturing step make proteins separate, approximately based on size, but aberrant migration of some proteins may occur. Different proteins may also stain differently, which interferes with quantification by staining. PAGE may also be used as a preparative technique for the purification of proteins. For example, quantitative preparative native continuous polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (QPNC-PAGE) is a method for separating native metalloproteins in complex biological matrices.

Chemical ingredients and their roles

Polyacrylamide gel (PAG) had been known as a potential embedding medium for sectioning tissues as early as 1964, and two independent groups employed PAG in electrophoresis in 1959.[11][12] It possesses several electrophoretically desirable features that make it a versatile medium. It is a synthetic, thermo-stable, transparent, strong, chemically relatively inert gel, and can be prepared with a wide range of average pore sizes.[13] The pore size of a gel is determined by two factors, the total amount of acrylamide present (%T) (T = Total concentration of acrylamide and bisacrylamide monomer) and the amount of cross-linker (%C) (C = bisacrylamide concentration). Pore size decreases with increasing %T; with cross-linking, 5%C gives the smallest pore size. Any increase or decrease in %C from 5% increases the pore size, as pore size with respect to %C is a parabolic function with vertex as 5%C. This appears to be because of non-homogeneous bundling of polymer strands within the gel. This gel material can also withstand high voltage gradients, is amenable to various staining and destaining procedures, and can be digested to extract separated fractions or dried for autoradiography and permanent recording.

Components

- Chemical buffer Stabilizes the pH value to the desired value within the gel itself and in the electrophoresis buffer. The choice of buffer also affects the electrophoretic mobility of the buffer counterions and thereby the resolution of the gel. The buffer should also be unreactive and not modify or react with most proteins. Different buffers may be used as cathode and anode buffers, respectively, depending on the application. Multiple pH values may be used within a single gel, for example in DISC electrophoresis. Common buffers in PAGE include Tris, Bis-Tris, or imidazole.

- Counterion balance the intrinsic charge of the buffer ion and also affect the electric field strength during electrophoresis. Highly charged and mobile ions are often avoided in SDS-PAGE cathode buffers, but may be included in the gel itself, where it migrates ahead of the protein. In applications such as DISC SDS-PAGE the pH values within the gel may vary to change the average charge of the counterions during the run to improve resolution. Popular counterions are glycine and tricine. Glycine has been used as the source of trailing ion or slow ion because its pKa is 9.69 and mobility of glycinate are such that the effective mobility can be set at a value below that of the slowest known proteins of net negative charge in the pH range. The minimum pH of this range is approximately 8.0.

- Acrylamide (C3H5NO; mW: 71.08). When dissolved in water, slow, spontaneous autopolymerization of acrylamide takes place, joining molecules together by head on tail fashion to form long single-chain polymers. The presence of a free radical-generating system greatly accelerates polymerization. This kind of reaction is known as Vinyl addition polymerisation. A solution of these polymer chains becomes viscous but does not form a gel, because the chains simply slide over one another. Gel formation requires linking various chains together. Acrylamide is carcinogenic,[14] a neurotoxin, and a reproductive toxin.[15] It is also essential to store acrylamide in a cool dark and dry place to reduce autopolymerisation and hydrolysis.

- Bisacrylamide (N,N′-Methylenebisacrylamide) (C7H10N2O2; mW: 154.17). Bisacrylamide is the most frequently used cross linking agent for polyacrylamide gels. Chemically it can be thought of as two acrylamide molecules coupled head to head at their non-reactive ends. Bisacrylamide can crosslink two polyacrylamide chains to one another, thereby resulting in a gel.

- Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) (C12H25NaO4S; mW: 288.38). (only used in denaturing protein gels) SDS is a strong detergent agent used to denature native proteins to unfolded, individual polypeptides. When a protein mixture is heated to 100 °C in presence of SDS, the detergent wraps around the polypeptide backbone. It binds to polypeptides in a constant weight ratio of 1.4 g SDS/g of polypeptide. In this process, the intrinsic charges of polypeptides become negligible when compared to the negative charges contributed by SDS. Thus polypeptides after treatment become rod-like structures possessing a uniform charge density, that is same net negative charge per unit weight. The electrophoretic mobilities of these proteins is a linear function of the logarithms of their molecular weights.

- Without SDS, different proteins with similar molecular weights would migrate differently due to differences in mass-charge ratio, as each protein has an isoelectric point and molecular weight particular to its primary structure. This is known as Native PAGE. Adding SDS solves this problem, as it binds to and unfolds the protein, giving a near uniform negative charge along the length of the polypeptide.

- Urea (CO(NH2)2; mW: 60.06). Urea is a chaotropic agent that increases the entropy of the system by interfering with intramolecular interactions mediated by non-covalent forces such as hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces. Macromolecular structure is dependent on the net effect of these forces, therefore it follows that an increase in chaotropic solutes denatures macromolecules,

- Ammonium persulfate (APS) (N2H8S2O8; mW: 228.2). APS is a source of free radicals and is often used as an initiator for gel formation. An alternative source of free radicals is riboflavin, which generated free radicals in a photochemical reaction.

- TEMED (N, N, N′, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine) (C6H16N2; mW: 116.21). TEMED stabilizes free radicals and improves polymerization. The rate of polymerisation and the properties of the resulting gel depend on the concentrations of free radicals. Increasing the amount of free radicals results in a decrease in the average polymer chain length, an increase in gel turbidity and a decrease in gel elasticity. Decreasing the amount shows the reverse effect. The lowest catalytic concentrations that allow polymerisation in a reasonable period of time should be used. APS and TEMED are typically used at approximately equimolar concentrations in the range of 1 to 10 mM.

Chemicals for processing and visualization

The following chemicals and procedures are used for processing of the gel and the protein samples visualized in it:

- Tracking dye. As proteins and nucleic acids are mostly colorless, their progress through the gel during electrophoresis cannot be easily followed. Anionic dyes of a known electrophoretic mobility are therefore usually included in the PAGE sample buffer. A very common tracking dye is Bromophenol blue (BPB, 3',3",5',5" tetrabromophenolsulfonphthalein). This dye is coloured at alkali and neutral pH and is a small negatively charged molecule that moves towards the anode. Being a highly mobile molecule it moves ahead of most proteins. As it reaches the anodic end of the electrophoresis medium electrophoresis is stopped. It can weakly bind to some proteins and impart a blue colour. Other common tracking dyes are xylene cyanol, which has lower mobility, and Orange G, which has a higher mobility.

- Loading aids. Most PAGE systems are loaded from the top into wells within the gel. To ensure that the sample sinks to the bottom of the gel, sample buffer is supplemented with additives that increase the density of the sample. These additives should be non-ionic and non-reactive towards proteins to avoid interfering with electrophoresis. Common additives are glycerol and sucrose.

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (CBB)(C45H44N3NaO7S2; mW: 825.97). CBB is the most popular protein stain. It is an anionic dye, which non-specifically binds to proteins. The structure of CBB is predominantly non-polar, and it is usually used in methanolic solution acidified with acetic acid. Proteins in the gel are fixed by acetic acid and simultaneously stained. The excess dye incorporated into the gel can be removed by destaining with the same solution without the dye. The proteins are detected as blue bands on a clear background. As SDS is also anionic, it may interfere with staining process. Therefore, large volume of staining solution is recommended, at least ten times the volume of the gel.

- Ethidium bromide (EtBr) is the traditionally most popular nucleic acid stain.

- Silver staining. Silver staining is used when more sensitive method for detection is needed, as classical Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining can usually detect a 50 ng protein band, Silver staining increases the sensitivity typically 50 times. The exact chemical mechanism by which this happens is still largely unknown.[16] Silver staining was introduced by Kerenyi and Gallyas as a sensitive procedure to detect trace amounts of proteins in gels.[17] The technique has been extended to the study of other biological macromolecules that have been separated in a variety of supports.[18] Many variables can influence the colour intensity and every protein has its own staining characteristics; clean glassware, pure reagents and water of highest purity are the key points to successful staining.[19] Silver staining was developed in the 14th century for colouring the surface of glass. It has been used extensively for this purpose since the 16th century. The colour produced by the early silver stains ranged between light yellow and an orange-red. Camillo Golgi perfected the silver staining for the study of the nervous system. Golgi's method stains a limited number of cells at random in their entirety.[20]

- Western blotting is a process by which proteins separated in the acrylamide gel are electrophoretically transferred to a stable, manipulable membrane such as a nitrocellulose, nylon, or PVDF membrane. It is then possible to apply immunochemical techniques to visualise the transferred proteins, as well as accurately identify relative increases or decreases of the protein of interest. For more, see Western blot.

See also

- Capillary electrophoresis

- DNA electrophoresis

- Eastern blotting

- Electroblotting

- Electrophoresis

- Fast parallel proteolysis (FASTpp) [21]

- Gel electrophoresis

- History of electrophoresis

- Isoelectric focusing

- Isotachophoresis

- Native Gel Electrophoresis

- Northern blotting

- Protein electrophoresis

- Southern blotting

- Two dimensional SDS-PAGE

- Western blotting

- Zymography

References

- ↑ Rath, Arianna and Glibowicka, Mira and Nadeau, Vincent G. and Chen, Gong and Deber, Charles M. (2009). "Detergent binding explains anomalous SDS-PAGE migration of membrane proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (6): 1760–1765. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813167106.

- ↑ Shapiro AL; Viñuela E; Maizel JV Jr. (September 1967). "Molecular weight estimation of polypeptide chains by electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels.". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 28 (5): 815–820. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(67)90391-9. PMID 4861258.

- ↑ Weber K, Osborn M (August 1969). "The reliability of molecular weight determinations by dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.". J Biol Chem. 244 (16): 4406–4412. PMID 5806584.

- ↑ Laemmli UK (August 1970). "Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4". Nature. 227 (5259): 680–685. doi:10.1038/227680a0. PMID 5432063.

- ↑ Caprette, David. "SDS-PAGE". Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ↑ "What is the meaning of de -gas the acrylamide gel mix?". Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ↑ "SDS-PAGE". Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ↑ Laemmli UK (August 1970). "Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4". Nature. 227 (5259): 680–685. doi:10.1038/227680a0. PMID 5432063.

- ↑ Schägger H, von Jagow G (Nov 1987). "Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa". Anal Biochem. 166 (2): 368–379. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. PMID 2449095.

- ↑ Andrews. "SDS-PAGE". Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ↑ Davis BJ, Ornstein L (1959). "A new high resolution electrophoresis method.". Delivered at the Society for the Study of Blood at the New York Academy of Medicine.

- ↑ Raymond S, Weintraub L (1959). "Acrylamide gel as a supporting medium for zone electrophoresis.". Science. 130 (3377): 711. doi:10.1126/science.130.3377.711. PMID 14436634.

- ↑ Rüchel R, Steere RL, Erbe EF (1978). "Transmission-electron microscopic observations of freeze-etched polyacrylamide gels". J Chromatogr. 166 (2): 563–575. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)95641-3.

- ↑ Tareke, E; Rydberg, P; Eriksson, S; Törnqvist, M (2000). "Acrylamide: a cooking carcinogen?". Chemical research in toxicology. 13 (6): 517–522. doi:10.1021/tx9901938.

- ↑ LoPachin, Richard (2004). "The changing view of acrylamide neurotoxicity". Neurotoxicology. 25 (4): 617–630. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2004.01.004.

- ↑ Golgi C (1873). "Sulla struttura della sostanza grigia del cervello". Gazzetta Medica Italiana (Lombardia). 33: 244–246.

- ↑ Kerenyi L, Gallyas F (1973). "Über Probleme der quantitiven Auswertung der mit physikalischer Entwicklung versilberten Agarelektrophoretogramme". Clin. Chim. Acta. 47 (3): 425–436. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(73)90276-3. PMID 4744834.

- ↑ Switzer RC 3rd, Merril CR, Shifrin S (Sep 1979). "A highly sensitive silver stain for detecting proteins and peptides in polyacrylamide gels". Anal. Biochem. 98 (1): 231–237. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(79)90732-2. PMID 94518.

- ↑ Hempelmann E, Schulze M, Götze O (1984). "Free SH-groups are important for the polychromatic staining of proteins with silver nitrat". Neuhof V (ed)Electrophoresis '84 , Verlag Chemie Weinheim 1984: 328–330.

- ↑ Grant G (Oct 2007). "How the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared between Golgi and Cajal". Brain Res Rev. 55 (2): 490–498. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.004. PMID 17306375.

- ↑ Minde DP (2012). "Determining biophysical protein stability in lysates by a fast proteolysis assay, FASTpp". PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e46147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046147. PMC 3463568

. PMID 23056252.

. PMID 23056252.

External links

| Library resources about Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

- SDS-PAGE: How it Works

- SDS-PAGE Video Protocol

- Demystifying SDS-PAGE Video

- Demystifying SDS-PAGE

- SDS-PAGE Calculator for customised recipes for TRIS Urea gels.

- 2-Dimensional Protein Gelelectrophoresis

- Hempelmann E. SDS-Protein PAGE and Proteindetection by Silverstaining and Immunoblotting of Plasmodium falciparum proteins. in: Moll K, Ljungström J, Perlmann H, Scherf A, Wahlgren M (eds) Methods in Malaria Research, 5th edition, 2008, 263-266