Photorespiration

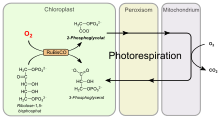

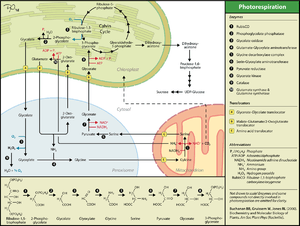

Photorespiration (also known as the oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle, or C2 photosynthesis) refers to a process in plant metabolism where the enzyme RuBisCO oxygenates RuBP, causing some of the energy produced by photosynthesis to be wasted. The desired reaction is the addition of carbon dioxide to RuBP (carboxylation), a key step in the Calvin–Benson cycle, however approximately 25% of reactions by RuBisCO instead add oxygen to RuBP (oxygenation), creating a product that cannot be used within the Calvin–Benson cycle. This process reduces the efficiency of photosynthesis, potentially reducing photosynthetic output by 25% in C3 plants.[1] Photorespiration involves a complex network of enzyme reactions that exchange metabolites between chloroplasts, leaf peroxisomes and mitochondria.

The oxygenation reaction of RuBisCO is a wasteful process because 3-phosphoglycerate is created at a reduced rate and higher metabolic cost compared with RuBP carboxylase activity. While photorespiratory carbon cycling results in the formation of G3P eventually, there is still a net loss of carbon (around 25% of carbon fixed by photosynthesis is re-released as CO2)[2] and nitrogen, as ammonia. Ammonia must be detoxified at a substantial cost to the cell. Photorespiration also incurs a direct cost of one ATP and one NAD(P)H.

While it is common to refer to the entire process as photorespiration, technically the term refers only to the metabolic network which acts to rescue the products of the oxygenation reaction (phosphoglycolate).

Photorespiratory reactions

Addition of molecular oxygen to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate produces 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA) and 2-phosphoglycolate (2PG, or PG). PGA is the normal product of carboxylation, and productively enters the Calvin cycle. Phosphoglycolate, however, inhibits certain enzymes involved in photosynthetic carbon fixation (hence is often said to be an 'inhibitor of photosynthesis').[3] It is also relatively difficult to recycle: in higher plants it is salvaged by a series of reactions in the peroxisome, mitochondria, and again in the peroxisome where it is converted into glycerate. Glycerate reenters the chloroplast and by the same transporter that exports glycolate. A cost of 1 ATP is associated with conversion to 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA) (Phosphorylation), within the chloroplast, which is then free to re-enter the Calvin cycle.

There are several costs associated with this metabolic pathway; one being the production of hydrogen peroxide in the peroxisome (associated with the conversion of glycolate to glyoxylate). Hydrogen peroxide is a dangerously strong oxidant which must be immediately broken down into water and oxygen by the enzyme catalase. The conversion of 2x 2Carbon glycine to 1 C3 serine in the mitochondria by the enzyme glycine-decarboxylase is a key step, which releases CO2, NH3, and reduces NAD to NADH. Thus, 1 CO

2 molecule is produced for every 3 molecules of O

2 (two deriving from the activity of RuBisCO, the third from peroxisomal oxidations).

The assimilation of NH3 occurs via the GS-GOGAT cycle, at a cost of one ATP and one NADPH.

Cyanobacteria have three possible pathways through which they can metabolise 2-phosphoglycolate. They are unable to grow if all three pathways are knocked out, despite having a carbon concentrating mechanism that should dramatically reduce the rate of photorespiration (see below).[4]

Substrate specificity of RuBisCO

The oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle reaction is catalyzed by RuBP oxygenase activity:

- RuBP + O

2 → Phosphoglycolate + 3-phosphoglycerate + 2H+

During the catalysis by RuBisCO, an 'activated' intermediate is formed (an enediol intermediate) in the RuBisCO active site. This intermediate is able to react with either CO

2 or O

2. It has been demonstrated that the specific shape of the RuBisCO active site acts to encourage reactions with CO

2. Although there is a significant "failure" rate (~25% of reactions are oxygenation rather than carboxylation), this represents significant favouring of CO

2, when the relative abundance of the two gasses is taken into account: in the current atmosphere, O

2 is approximately 500 times more abundant, and in solution O

2 is 25X more abundant than CO

2.[5]

The ability of RuBisCO to specify between the two gasses is known as its selectivity factor (or Srel), and it varies between species,[5] with angiosperms more efficient than other plants, but with little variation among the vascular plants.[6]

A suggested explanation into RuBisCO's inability to discriminate completely between CO

2 and O

2 is that it is an evolutionary relic: The early atmosphere in which primitive plants originated contained very little oxygen, the early evolution of RuBisCO was not influenced by its ability to discriminate between O

2 and CO

2.[6]

Conditions which increase photorespiration

Photorespiration rates are increased by:

Altered substrate availability: lowered CO2 or increased O2

Factors which influence this include the atmospheric abundance of the two gases, the supply of the gases to the site of fixation (i.e. in land plants: whether the stomata are open or closed), the length of the liquid phase (how far these gases have to diffuse through water in order to reach the reaction site). For example, when the stomata are closed to prevent water loss during drought: this limits the CO2 supply, while O

2 production within the leaf will continue. In algae (and plants which photosynthesise underwater); gases have to diffuse significant distances through water, which results in a decrease in the availability of CO2 relative to O

2. It has been predicted that the increase in ambient CO2 concentrations predicted over the next 100 years may reduce the rate of photorespiration in most plants by around 50%.

Increased temperature

At higher temperatures RuBisCO is less able to discriminate between CO2 and O

2. This is because the enediol intermediate is less stable. Increasing temperatures also reduce the solubility of CO2, thus reducing the concentration of CO2 relative to O

2 in the chloroplast.

Biological adaptation to minimize photorespiration

Certain species of plants or algae have mechanisms to reduce uptake of molecular oxygen by RuBisCO. These are commonly referred to as Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs), as they increase the concentration of CO

2 so that RuBisCO is less likely to produce glycolate through reaction with O

2.

Biochemical carbon concentrating mechanisms

Biochemical CCMs concentrate carbon dioxide in one temporal or spatial region, through metabolite exchange. C4 and CAM photosynthesis both use the enzyme Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) to add CO

2 to a 3-Carbon sugar. PEPC is faster than RuBisCO, and more selective for CO

2.

C4

C4 plants capture carbon dioxide in their mesophyll cells (using an enzyme called Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase which catalyzes the combination of carbon dioxide with a compound called Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)), forming oxaloacetate. This oxaloacetate is then converted to malate and is transported into the bundle sheath cells (site of carbon dioxide fixation by RuBisCO) where oxygen concentration is low to avoid photorespiration. Here, carbon dioxide is removed from the malate and combined with RuBP by RuBisCO in the usual way, and the Calvin cycle proceeds as normal. The CO

2 concentrations in the Bundle Sheath are approximately 10-20 fold higher than the concentration in the mesophyll cells.[6]

This ability to avoid photorespiration makes these plants more hardy than other plants in dry and hot environments, wherein stomata are closed and internal carbon dioxide levels are low. Under these conditions, photorespiration does occur in C4 plants, but at a much reduced level compared with C3 plants in the same conditions. C4 plants include sugar cane, corn (maize), and sorghum.

CAM (Crassulacean acid metabolism)

CAM plants, such as cacti and succulent plants, also use the enzyme PEP carboxylase to capture carbon dioxide, but only at night. Crassulacean acid metabolism allows plants to conduct most of their gas exchange in the cooler night-time air, sequestering carbon in 4 carbon sugars which can be released to the photosynthesizing cells during the day. This allows CAM plants to reduce water loss (transpiration) by maintaining closed stomata during the day. CAM plants usually display other water-saving characteristics, such as thick cuticles, stomata with small apertures, and typically lose around 1/3 of the amount of water per CO

2 fixed.[7]

Algae

There have been some reports of algae operating a biochemical CCM: shuttling metabolites within single cells to concentrate CO2 in one area. This process is not fully understood.[8]

Biophysical carbon-concentrating mechanisms

This type of carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM) relies on a contained compartment within the cell into which CO2 is shuttled, and where RuBisCO is highly expressed. In many species, biophysical CCMs are only induced under low carbon dioxide concentrations. Biophysical CCMs are more evolutionarily ancient than biochemical CCMs. There is some debate as to when biophysical CCMs first evolved, but it is likely to have been during a period of low carbon dioxide, after the Great Oxygenation Event (2.4 billion years ago). Low CO

2 periods occurred around 750, 650, and 320-270 million years ago.[9]

Eukaryotic algae

In nearly all species of eukaryotic algae (Chloromonas being one notable exception), upon induction of the CCM, ~95% of RuBisCO is densely packed into a single subcellular compartment: the pyrenoid. Carbon dioxide is concentrated in this compartment using a combination of CO2 pumps, bicarbonate pumps, and carbonic anhydrases. The pyrenoid is not a membrane bound compartment, but is found within the chloroplast, often surrounded by a starch sheath (which is not thought to serve a function in the CCM).[10]

Hornworts

Certain species of hornwort are the only land plants which are known to have a biophysical CCM involving concentration of carbon dioxide within pyrenoids in their chloroplasts.

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacterial CCMs are similar in principle to those found in eukaryotic algae and hornworts, but the compartment into which carbon dioxide is concentrated has several structural differences. Instead of the pyrenoid, cyanobacteria contain carboxysomes, which have a protein shell, and linker proteins packing RuBisCO inside with a very regular structure. Cyanobacterial CCMs are much better understood than those found in eukaryotes, partly due to the ease of genetic manipulation of prokaryotes.

Possible purpose of photorespiration

Reducing photorespiration may not result in increased growth rates for plants. Photorespiration may be necessary for the assimilation of nitrate from soil. Thus, a reduction in photorespiration by genetic engineering or because of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide due to fossil fuel burning may not benefit plants as has been proposed.[11] Several physiological processes may be responsible for linking photorespiration and nitrogen assimilation. Photorespiration increases availability of NADH, which is required for the conversion of nitrate to nitrite. Certain nitrite transporters also transport bicarbonate, and elevated CO2 has been shown to suppress nitrite transport into chloroplasts.[12]

Although photorespiration is greatly reduced in C4 species, it is still an essential pathway - mutants without functioning 2-phosphoglycolate metabolism cannot grow in normal conditions. One mutant was shown to rapidly accumulate glycolate.[13]

Although the functions of photorespiration remain controversial,[14] it is widely accepted that this pathway influences a wide range of processes from bioenergetics, photosystem II function, and carbon metabolism to nitrogen assimilation and respiration. The photorespiratory pathway is a major source of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) in photosynthetic cells. Through H

2O

2 production and pyridine nucleotide interactions, photorespiration makes a key contribution to cellular redox homeostasis. In so doing, it influences multiple signalling pathways, in particular, those that govern plant hormonal responses controlling growth, environmental and defense responses, and programmed cell death.[14]

Another theory postulates that it may function as a "safety valve",[15] preventing the excess of reductive potential coming from an overreduced NADPH-pool from reacting with oxygen and producing free radicals, as these can damage the metabolic functions of the cell by subsequent oxidation of membrane lipids, proteins or nucleotides.

See also

References

- ↑ Sharkey, Thomas (1988). "Estimating the rate of photorespiration in leaves". Physiologia Plantarum. 73 (1): 147–152. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1988.tb09205.x.

- ↑ Leegood, R. C. (2007). A welcome diversion from photorespiration. Nature Biotechnology, 25(5), 539–540.

- ↑ Peterhansel, C.; Krause, K.; Braun, H. -P.; Espie, G. S.; Fernie, A. R.; Hanson, D. T.; Keech, O.; Maurino, V. G.; Mielewczik, M.; Sage, R. F. (2012). "Engineering photorespiration: Current state and future possibilities". Plant Biology. 15 (4): n/a. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00681.x.

- ↑ Eisenhut, M.; Ruth, W.; Haimovich, M.; Bauwe, H.; Kaplan, A.; Hagemann, M. (2008). "The photorespiratory glycolate metabolism is essential for cyanobacteria and might have been conveyed endosymbiontically to plants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (44): 17199. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807043105.

- 1 2 Griffiths, H. (2006). Designs on Rubisco" Nature 441(7096), 940–941. Retrieved from http://www.rsbs.anu.edu.au/profiles/graham_farquhar/documents/233TcherkezPNASNaturecommentary.pdf

- 1 2 3 Ehleringer, J. R.; Sage, R. F.; Flanagan, L. B.; Pearcy, R. W. (1991). "Climate change and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 6 (3): 95–99. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(91)90183-x.

- ↑ Plant Physiology, Fifth Edition - Sinauer Associates, Inc. Taiz and Zeiger. 2010. Chapter 8, Page 222

- ↑ Giordano, Mario; Beardall, John; Raven, John A. (June 2005). "CO2 CONCENTRATING MECHANISMS IN ALGAE: Mechanisms, Environmental Modulation, and Evolution". Annual Review of Plant Biology. Annual Reviews. 56 (1): 99–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144052. PMID 15862091. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Raven, J. A.; Giordano, M.; Beardall, J.; Maberly, S. C. (2012). "Algal evolution in relation to atmospheric CO2: Carboxylases, carbon-concentrating mechanisms and carbon oxidation cycles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1588): 493. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0212.

- ↑ Villarejo, A.; Martinez, F.; Pino Plumed, M.; Ramazanov, Z. (1996). "The induction of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in a starch-less mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii". Physiologia Plantarum. 98 (4): 798. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb06687.x.

- ↑ Rachmilevitch S, Cousins AB, Bloom AJ (August 2004). "Nitrate assimilation in plant shoots depends on photorespiration". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (31): 11506–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404388101. PMC 509230

. PMID 15272076.

. PMID 15272076. - ↑ Bloom, A. J.; Burger, M.; Asensio, J. S. R.; Cousins, A. B. (2010). "Carbon Dioxide Enrichment Inhibits Nitrate Assimilation in Wheat and Arabidopsis". Science. 328 (5980): 899–903. doi:10.1126/science.1186440. PMID 20466933.

- ↑ Zabaleta, E.; Martin, M. V.; Braun, H. P. (2012). "A basal carbon concentrating mechanism in plants?". Plant Science. 187: 97–104. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.02.001. PMID 22404837.

- 1 2 Foyer, C. H.; Bloom, A. J.; Queval, G.; Noctor, G. (2009). "Photorespiratory Metabolism: Genes, Mutants, Energetics, and Redox Signaling". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 60 (1): 455–484. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.091948. PMID 19575589.

- ↑ Stuhlfauth, t.; Scheuermann, R; Fock, H. P. (1990). "Light Energy Dissipation under Water Stress Conditions". Plant Physiology. 92 (4): 1053–1061. doi:10.1104/pp.92.4.1053. PMC 1062415

. PMID 16667370.

. PMID 16667370.

- Stern, Kingsley (2003). Introductory Plant Biology. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-290941-2.

- Siedow, James N.; Day, David (2000). "14. Respiration and Photorespiration". Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants. American Society of Plant Physiologists.

.svg.png)