Color difference

The difference or distance between two colors is a metric of interest in color science. It allows quantified examination of a notion that formerly could only be described with adjectives. Quantification of these properties is of great importance to those whose work is color critical. Common definitions make use of the Euclidean distance in a device independent color space.

Delta E

The International Commission on Illumination (CIE) calls their distance metric ΔE*ab (also called ΔE*, dE*, dE, or "Delta E") where delta is a Greek letter often used to denote difference, and E stands for Empfindung; German for "sensation". Use of this term can be traced back to the influential Hermann von Helmholtz and Ewald Hering.[1][2]

Different studies have proposed different ΔE values that have a JND (just noticeable difference). Unempirically, a value of '1.0' is often mentioned, but in a recent study, Mahy et al. (1994) assessed a JND of 2.3 ΔE. However, perceptual non-uniformities in the underlying CIELAB color space prevent this and have led to the CIE's refining their definition over the years, leading to the superior (as recommended by the CIE) 1994 and 2000 formulas.[3] These non-uniformities are important because the human eye is more sensitive to certain colors than others. A good metric should take this into account in order for the notion of a "just noticeable difference" to have meaning. Otherwise, a certain ΔE that may be insignificant between two colors that the eye is insensitive to may be conspicuous in another part of the spectrum.[4]

CIE76

The 1976 formula is the first color-difference formula that related a measured to a known set of CIELAB coordinates. This formula has been succeeded by the 1994 and 2000 formulas because the CIELAB space turned out to be not as perceptually uniform as intended, especially in the saturated regions. This means that this formula rates these colors too highly as opposed to other colors.

Using and , two colors in L*a*b*:

corresponds to a JND (just noticeable difference).[5]

CIE94

The 1976 definition was extended to address perceptual non-uniformities, while retaining the L*a*b* color space, by the introduction of application-specific weights derived from an automotive paint test's tolerance data.[6]

ΔE (1994) is defined in the L*C*h* color space with differences in lightness, chroma and hue calculated from L*a*b* coordinates. Given a reference color[7] and another color , the difference is:[8][9][10]

where:

and where kC and kH are usually both unity and the weighting factors kL, K1 and K2 depend on the application:

| graphic arts | textiles | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| 0.045 | 0.048 | |

| 0.015 | 0.014 |

Geometrically, the quantity corresponds to the arithmetic mean of the chord lengths of the equal chroma circles of the two colors. [11]

CIEDE2000

Since the 1994 definition did not adequately resolve the perceptual uniformity issue, the CIE refined their definition, adding five corrections:[12][13]

- A hue rotation term (RT), to deal with the problematic blue region (hue angles in the neighborhood of 275°):[14]

- Compensation for neutral colors (the primed values in the L*C*h differences)

- Compensation for lightness (SL)

- Compensation for chroma (SC)

- Compensation for hue (SH)

- Note: The formulae below should use degrees rather than radians; the issue is significant for RT.

- The kL, kC, and kH are usually unity.

-

- Note: The inverse tangent (tan−1) can be computed using a common library routine

atan2(b, a′)which usually has a range from −π to π radians; color specifications are given in 0 to 360 degrees, so some adjustment is needed. The inverse tangent is indeterminate if both a′ and b are zero (which also means that the corresponding C′ is zero); in that case, set the hue angle to zero. See Sharma 2005, eqn. 7.

- Note: The inverse tangent (tan−1) can be computed using a common library routine

-

- Note: When either C′1 or C′2 is zero, then Δh′ is irrelevant and may be set to zero. See Sharma 2005, eqn. 10.

-

- Note: When either C′1 or C′2 is zero, then H′ is h′1+h′2 (no divide by 2; essentially, if one angle is indeterminate, then use the other angle as the average; relies on indeterminate angle being set to zero). See Sharma 2005, eqn. 7 and p. 23 stating most implementations on the internet at the time had "an error in the computation of average hue".

CMC l:c (1984)

In 1984, the Colour Measurement Committee of the Society of Dyers and Colourists defined a difference measure, also based on the L*C*h color model. Named after the developing committee, their metric is called CMC l:c. The quasimetric has two parameters: lightness (l) and chroma (c), allowing the users to weight the difference based on the ratio of l:c that is deemed appropriate for the application. Commonly used values are 2:1[15] for acceptability and 1:1 for the threshold of imperceptibility.

The distance of a color to a reference is:[16]

CMC l:c is designed to be used with D65 and the CIE Supplementary Observer.[17]

Tolerance

Tolerancing concerns the question "What is a set of colors that are imperceptibly/acceptably close to a given reference?" If the distance measure is perceptually uniform, then the answer is simply "the set of points whose distance to the reference is less than the just-noticeable-difference (JND) threshold." This requires a perceptually uniform metric in order for the threshold to be constant throughout the gamut (range of colors). Otherwise, the threshold will be a function of the reference color—cumbersome as a practical guide.

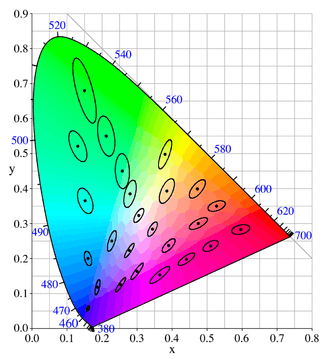

In the CIE 1931 color space, for example, the tolerance contours are defined by the MacAdam ellipse, which holds L* (lightness) fixed. As can be observed on the diagram on the right, the ellipses denoting the tolerance contours vary in size. It is partly this non-uniformity that led to the creation of CIELUV and CIELAB.

More generally, if the lightness is allowed to vary, then we find the tolerance set to be ellipsoidal. Increasing the weighting factor in the aforementioned distance expressions has the effect of increasing the size of the ellipsoid along the respective axis.[18]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Backhaus, W.; Kliegl, R.; Werner, J. S. (1998). Color Vision: Perspectives from Different Disciplines. Walter de Gruyter. p. 188. ISBN 9783110154313. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- ↑ Valberg, A. (2005). Light Vision Color. Wiley. p. 278. ISBN 9780470849026. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- ↑ Real World Color Management, Second Edition (Bruce Fraser)

- ↑ Evaluation of the CIE Color Difference Formulas

- ↑ Sharma, Gaurav (2003). Digital Color Imaging Handbook (1.7.2 ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0900-X.

- ↑ "Delta E: The Color Difference". Colorwiki.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ Called such because the operator is not commutative. This makes it a quasimetric.

- ↑ Lindbloom, Bruce Justin. "Delta E (CIE 1994)". Brucelindbloom.com. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ↑ "Colour Difference Software by David Heggie". Colorpro.com. 1995-12-19. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ "CIE 1976 L*a*b* Colour space draft standard" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ↑ Klein, Georg A. Industrial Color Physics. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4419-1196-4.

- ↑ Sharma, Gaurav; Wu, Wencheng; Dalal, Edul N. (2005). "The CIEDE2000 color-difference formula: Implementation notes, supplementary test data, and mathematical observations" (PDF). Color Research & Applications. Wiley Interscience. 30 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1002/col.20070.

- ↑ Lindbloom, Bruce Justin. "Delta E (CIE 2000)". Brucelindbloom.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ The "Blue Turns Purple" Problem, Bruce Lindbloom

- ↑ Meaning that the lightness contributes half as much to the difference (or, identically, is allowed twice the tolerance) as the chroma

- ↑ Lindbloom, Bruce Justin. "Delta E (CMC)". Brucelindbloom.com. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ↑ CMC

- ↑ Susan Hughes (14 January 1998). "A guide to Understanding Color Tolerancing" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-12-02.

Further reading

- Robertson, Alan R. (1990). "Historical development of CIE recommended color difference equations". Color Research & Application. 15 (3): 167–170. doi:10.1002/col.5080150308.

- Melgosa, M.; Quesada, J. J.; Hita, E. (December 1994). "Uniformity of some recent color metrics tested with an accurate color-difference tolerance dataset". Applied Optics. 33 (34): 8069–8077. doi:10.1364/AO.33.008069. PMID 20963027.

- McDonald, Roderick, ed. (1997). Colour Physics for Industry (second ed.). Society of Dyers and Colourists. ISBN 0-901956-70-8.

External links

- Bruce Lindbloom's color difference calculator. Uses all metrics defined herein.

- The CIEDE2000 Color-Difference Formula, by Gaurav Sharma. Implementations in MATLAB and Excel.