Penny dreadful

Penny dreadful is a pejorative term used to refer to cheap popular serial literature produced during the nineteenth century in the United Kingdom. The term is roughly interchangeable with penny horrible, penny awful,[1] and penny blood.[2] The term typically referred to a story published in weekly parts, each costing one penny. The subject matter of these stories was typically sensational, focusing on the exploits of detectives, criminals, or supernatural entities. While the term "penny dreadful" was originally used in reference to a specific type of literature circulating in mid-Victorian Britain, it came to encompass a variety of publications that featured cheap sensational fiction, such as story papers and booklet "libraries". The penny dreadfuls were printed on cheap wood pulp paper and were aimed at young working class males.[3]

Origins

Victorian Era Britain experienced social changes that resulted in increased literacy rates. With the rise of capitalism and industrialisation, people began to spend more money on entertainment, contributing to the popularisation of the novel. Improvements in printing resulted in newspapers such as Joseph Addison’s The Spectator and Richard Steele’s The Tatler, and England's more fully recognizing the singular concept of reading as a form of leisure; it was, of itself, a new industry. Other significant changes included industrialisation and an increased capacity for travel via the invention of tracks, engines, and the corresponding railway distribution.

These changes created both a market for cheap popular literature, and the ability for it to be circulated on a large scale. The first penny serials were published in the 1830s to meet this demand.[4] The serials were priced to be affordable to working-class readers, and were considerably cheaper than the serialised novels of authors such as Charles Dickens, which cost a shilling [twelve pennies] per part.

Subject matter

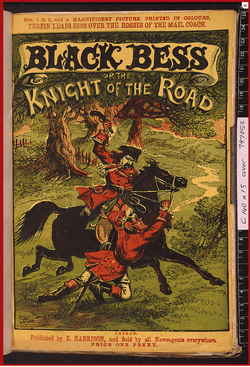

The stories themselves were reprints, or sometimes rewrites, of Gothic thrillers such as The Monk or The Castle of Otranto, as well as new stories about famous criminals. Some of the most famous of these penny part-stories were The String of Pearls: A Romance (introducing Sweeney Todd),[5] The Mysteries of London (inspired by the French serial The Mysteries of Paris), and Varney the Vampire. Highwaymen were popular heroes; Black Bess or the Knight of the Road, outlining the largely imaginary exploits of real-life English highwayman Dick Turpin, continued for 254 episodes. Other serials were thinly-disguised plagiarisms of popular contemporary literature. The publisher Edward Lloyd, for instance, published a number of penny serials derived from the works of Dickens entitled Oliver Twiss, Nickelas Nicklebery, and Martin Guzzlewit.[6]

Working class boys who could not afford a penny a week often formed clubs that would share the cost, passing the flimsy booklets from reader to reader. Other enterprising youngsters would collect a number of consecutive parts, then rent the volume out to friends.

In 1866, Boys of England was introduced as a new type of publication, an eight-page magazine that featured serial stories as well as articles and shorts of interest. It was printed on the same cheap paper, though it sported a larger format than the penny parts.

Numerous competitors quickly followed, with such titles as Boys' Leisure Hour, Boys' Standard, Young Men of Great Britain, etc. As the price and quality of other types of fiction works were the same, these also fell under the general definition of penny dreadfuls.

American dime novels were edited and rewritten for a British audience. These appeared in booklet form, such as the Boy's First Rate Pocket Library. Frank Reade, Buffalo Bill, and Deadwood Dick were all popular with the penny dreadful audience.

The penny dreadfuls were influential since they were, in the words of one commentator, “the most alluring and low-priced form of escapist reading available to ordinary youth, until the advent in the early 1890s of future newspaper magnate Alfred Harmsworth’s price-cutting ‘halfpenny dreadfuller’”[7]

In reality, the serial novels were overdramatic and sensational, but generally harmless. If anything, the penny dreadfuls, although obviously not the most enlightening or inspiring of literary selections, resulted in increasingly literate youth in the Industrial period. The wide circulation of this sensationalist literature, however, contributed to an ever greater fear of crime in mid-Victorian Britain.[8]

Decline

The popularity of penny dreadfuls was challenged, in the 1890s, by the rise of competing literature. Leading the challenge were popular periodicals published by Alfred Harmsworth. Priced at one half-penny, Harmsworth's story papers were cheaper and, at least initially, were more respectable than the competition. Harmsworth claimed to be motivated by a wish to challenge the pernicious influence of penny dreadfuls. In an editorial in the first number of The Half-penny Marvel in 1893 it was stated that:

It is almost a daily occurrence with magistrates to have before them boys who, having read a number of 'dreadfuls', followed the examples set forth in such publications, robbed their employers, bought revolvers with the proceeds, and finished by running away from home, and installing themselves in the back streets as 'highwaymen'. This and many other evils the 'penny dreadful' is responsible for. It makes thieves of the coming generation, and so helps fill our gaols.[9]

The Half-penny Marvel was soon followed by a number of other Harmsworth half-penny periodicals, such as The Union Jack and Pluck. At first the stories were high-minded moral tales, reportedly based on true experiences, but it was not long before these papers started using the same kind of material as the publications they competed against. A.A. Milne once said, "Harmsworth killed the penny dreadful by the simple process of producing the ha'penny dreadfuller." The quality of the Harmsworth/Amalgamated Press papers began to improve throughout the early 20th century, however. By the time of the First World War, papers such as Union Jack dominated the market.[10]

Legacy

Two popular characters to come out of the penny dreadfuls were Jack Harkaway, introduced in the Boys of England in 1871, and Sexton Blake, who began in the Half-penny Marvel in 1893. In 1904, the Union Jack became "Sexton Blake's own paper", and he appeared in every issue thereafter, up until the paper's demise in 1933. In total, Blake appeared in roughly 4,000 adventures, right up into the 1970s, a record exceeded only by Nick Carter and Dixon Hawke. Harkaway was also popular in America and had many imitators.

The fictional Sweeney Todd, the subject of both a successful musical by Stephen Sondheim and a feature film by Tim Burton, also first appeared in an 1846/1847 penny dreadful titled The String of Pearls: A Romance.

Over time, the penny dreadfuls evolved into the British comic magazines. Owing to their cheap production, their perceived lack of value, and such hazards as war-time paper drives, the penny dreadfuls, particularly the earliest ones, are fairly rare today.

Some items that have been named after this topic include a song called "Penny Dreadfuls" by Animal Collective, the Irish literary magazine The Penny Dreadful[11] and a Showtime horror television series set in Victorian England titled Penny Dreadful.

See also

References

- ↑ Zimmer, Ben. "Horribles and terribles", Language Log, accessed 4 June 2011

- ↑ Many people use the term "penny blood" interchangeably with "penny dreadful". Sally Powell distinguishes between these terms, however, and designates "penny bloods" as cheap sensational literature written largely for working-class adults. Powell, p. 46

- ↑ James, Louis (1974). Fiction for the Working Man, 1830-50. Harmondsworth: Penguin University Books. ISBN 0-14-060037-X. p.20

- ↑ Turner, E. S. (1975). Boys Will be Boys. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-004116-8. p.20

- ↑ "Penny Dreadful: From True Crime to Fiction > Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street in Concert". KQED-TV. Archived from the original on February 21, 2003. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ↑ Turner, E. S. (1975). Boys Will be Boys. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-004116-8. p.20

- ↑ Springhall, John (1994). "Disseminating Impure Literature': The 'Penny Dreadful' Publishing Business Since 1860". Economic Historical Review. 47 (3).

- ↑ Casey, Christopher (Winter 2011). "Common Misperceptions: The Press and Victorian Views of Crime". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 41 (3).

- ↑ Springhall, John, Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, p.75

- ↑ Editorials in early issues of papers such as the Union Jack or Boys' Friend make frequent references to "the blood and thunders", but as time went on the mentions disappeared. Letters sent in by parents or teachers were frequently printed, praising the papers for putting the "trash" out of business.

- ↑ "From Zine to Magazine. About, The Penny Dreadful, New Irish Writers". Thepennydreadful.org. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

Sources

- Anglo, Michael (1977). Penny Dreadfuls and Other Victorian Horrors. London: Jupiter. ISBN 0-904041-59-X.

- Carpenter, Kevin (1983). Penny Dreadfuls and comics : English periodicals for children from Victorian times to the present day. London: Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood. ISBN 0-905209-47-8.

- Casey, Christopher (2010). "Common Misperceptions: The Press and Victorian Views of Crime". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. Cambridge: MIT Press. 41 (3 - Winter 2011): 367–391. doi:10.1162/JINH_a_00106. PMID 21141651.

- Chesterton, G. K. (1901). A Defence of Penny Dreadfuls. London: The Daily News.

- Haining, Peter (1975). The Penny dreadful: or, Strange, horrid and sensational tales!. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-01779-1.

- James, Louis (1963). Fiction for the working man 1830–50. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140600377.

- Powell, Sally (2004). "Black Markets and Cadaverous Pies: The Corpse, Urban Trade and Industrial Consumption in the Penny Blood". In Andrew Maunder and Grace Moore (ed.). Victorian Crime Madness and Sensation. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-4060-4.

External links

| Look up penny dreadful in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Penny dreadfuls. |

- Black Bess or, The knight of the road. A tale of the good old times

- British Library collection of images from penny dreadfuls

- Marie Léger-St-Jean. "Price One Penny: Cheap Literature, 1837-1860". University of Cambridge. (Bibliographic database of early Victorian penny fiction)