Pediatric acquired brain injury

Pediatric acquired brain injury (PABI) is the number one cause of death and disability for children and young adults in the United States." and effects most children ages (6-10) and adolescent ages (11-17) around the world. The injury can be traumatic or non-traumatic in nature, and most patients never return to normal after suffering from the injury.

There are many different symptoms such as amnesia, anhedonia, and apraxia. Currently there isn’t a cure for the injury. PABI effects the family of the patient also, because the families of the patient will need to adapt to the new changes they will experience in their child. It is recommended that the families decide to gain as much information as they can about the injury and what to expect by going to different program events and meetings.

Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury

The term "pediatric" in this case encompasses brain injuries sustained from birth up to age 25, since the developing brain does not finish maturing until that time. An acquired brain injury (ABI) can be sustained from traumatic brain injury (TBI) such as falls, motor vehicle incidents, sports concussions, blast injuries from war, assaults/child abuse, gunshot wounds, etc.) and non-traumatic brain injury (i.e. stroke, brain tumors, infection, poisoning, hypoxia, ischemia, encephalopathy or substance abuse).

Pathophysiology of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury

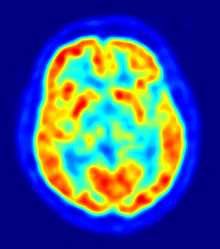

The pediatric brain undergoes dramatic changes and significant pruning of neural networks throughout development. Whereby the areas for primary senses and motor skills are mostly developed by age 4, other areas, like the frontal cortices involved in higher level reasoning, decision-making, emotion, and impulsivity continue to develop well into the late teens to early 20's. Therefore, the patient’s age and brain developmental state influence what neuronal systems become most affected post-injury.[1] Key structural features of the pediatric brain make the brain tissue more susceptible to the mechanical injury during TBI than the adult brain: a larger water content in the brain tissue and reduced myelination results in diminished shear resistance after injury. It has also been shown that more immature brains have an enlarged extracellular space volume and a decreased expression of glial aquaporin 4 leading to an increased incidence of brain swelling after TBI.[2] Along with a delayed decrease in cerebral blood flow, these unique features of the developing brain can mediate further secondary damage, through hypoxia, excitotoxicity, free radical damage, and neuroinflammation after the primary injury.[1][2] Even properties of these secondary events differ between the developing brain and the adult brain: (1) in the developing brain, the overexpression and activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R) leads to an increased calcium influx and an increased capacity for excitoxicity when compared to the adult brain and (2) the developing brain has lower glutathione peroxidase activity and a decreased ability to maintain stores of glutathione peroxidase, therefore the developing brain is more vulnerable to oxidative stress than the adult brain.[2] Damage to the developing brain, by any of the above mechanisms, can disturb neuronal maturation, leading to neuronal loss, axonal destruction, and demyelination.[3]

Neurocognitive Problems in Children After Traumatic Brain Injury

Delayed physiological responses post-TBI can lead to neurodegeneration in various parts of the brain in both chronic and severe cases in children. The parts of the brain that have been proven to be affected include: the hippocampus, amygdala, globus pallidus, thalamus, periventricular white matter, cerebellum, and brainstem.[4] As a result, this can lead to behavioral and cognitive problems in child development. Behavioral changes have been characterized as "externalizing" and "internalizing" problems.[5] Externalizing problems include different forms of aggression, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. The most common of these problems result from changes in attention and focus, such as ADHD.[6] Internalizing issues include psychiatric problems such as short-term and long-term depression, anxiety, personality disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Several variables can determine the outcome of behavioral problems in children post-TBI. For example, children that are already suffer from behavioral issues before injury are more likely to develop long-term cognitive problems.[7] Another important factor is the severity of the injury, which can be a predictor of how long behavioral symptoms last and if they will increase over time.

Statistically about 54% to 63% of children develop novel psychiatric disorders about 24 months after severe TBI, and 10% to 21% after mild or moderate TBI, the most common of which is personality change due to TBI. The symptoms may last for 6 to 24 months on average.[8] Development of PTSD is common (68%) in the first few weeks post-injury with a decline in the course of 2 years. In cases of severe TBI about one third of children develop depressive disorder.[8] Children with severe TBI also have some effects on working memory, visual immediate memory, and more prominent consequences in intellectual functioning, executive functioning (including speed processing and attention), and verbal immediate and delayed memory. Some recovery is observed during the first 2 years post-injury.[9] Children with moderate TBI only show some decline in attention and problem solving, but larger effects in visual immediate memory.[9] The superior frontal lesions correlate with the type of outcome, but more importantly, subcortical network damage may affect the recovery due to the lesions in white matter tracts.[8] Children with severe TBI are at higher risk for not achieving developmentally appropriate gains and not catching up with peers at school due to the crucial stage of learning at which their neural networks are disrupted by the injury.[9]

Behavior of Those Suffering from Pediatric Brain Injury

In children and adolescents that have an acquired brain injury, the cognitive and emotional difficulties that come about from their injury can negatively impact their level of participation in home, school and other social situations. This puts the patient at a disadvantage because they won’t nearly as social, or able to participate in a school setting as an ordinary child would. Involvement in social situations is important for the normal development of children as a means of gaining an understanding of how to effectively work together with others. Group work is a huge factor is academics today, and the child’s ability to work within groups will be ineffective. Furthermore, young people with an acquired brain injury are often reported as having insufficient problem solving skills. This has the potential to hinder their performance in various academic and social settings further. It is important for rehabilitation programs to deal with these challenges specific to children who have not fully developed at the time of their injury.

Symptoms

Some symptoms that result from an acquired brain injury are amnesia, anhedonia, and apraxia.

Amnesia

"Childhood amnesia is the inability to remember one’s own childhood." Researchers found that some everyday activities such as speaking, running, or playing a guitar, cannot be described or remembered.

Anhedonia

A child that is diagnosed with anhedonia would lack interest in some usual activities, such as hobbies, playing sports, or engaging with friends. It’s very essential for a child to be able to enjoy fun childhood activities because it can help them build a social life, and easily interact with others. Not being able to do these things at a young age will only make it harder to adapt as the child gets older.

Apraxia

"Apraxia is the inability to execute learned purposeful movements, despite having the desire and the physical capacity to perform the movements." In this case, the child could have still have the memory of doing a usual activity such as riding a bike, but still not be able to accomplish the movement.

Training

There are many different ways to "train" the children diagnosed with Pediatric Brain Injury. The training mainly tests their brain, to see exactly what’s wrong with the patient, and what areas need to be focused on for improvement.

AIM Program

"AIM is a 10-week, computerized treatment program that incorporates goal setting, the use of metacognitive strategies, and computer-based exercises designed to improve various aspects of attention."[10] "During the initial meeting with the child, the computer program leads the clinician through an intake procedure that assists in identifying the nature and severity of the child’s attention difficulties and then facilitates the selection of attention training tasks and metacognitive strategies tailored to the needs of the child." The clinician’s role is to select the specific, presenting mental areas that are impaired, as well as to modify the tasks and strategies in response to improvements of the patients’ overtime.[10] This is a helpful way to figure out what problems the child/adolescent is facing, while also helping them to gradually improve their injury.

Parent’s Assistance for Patients

"Investigators have established that interventions for pediatric BI should target the family because changes in one family member will affect the entire family system."[11] "During rehabilitation, caregivers often receive skills training to improve their ability to care for their child after their brain injury.[11] Family realignment and adjusting the child’s environment are two major ways parents can make the distresses of the injury easier on their child. Some beneficial ways parents can realign their household are applying consequences to minimize problem behaviors, increasing the amount of positive communication between parents and child with injury, and establishing positive routines that will instill meaning into the child’s day-to-day life.[11]

The Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury Community Outreach Program (PABICOP)

The team includes several members: a pediatric neurologist, a community outreach coordinator, school liaison personnel, an occupational therapist, and a speech language pathologist."[12]

"The philosophy of the comprehensive acquired brain injury program for children/youth is that it be holistic, and parent and family centered, and that it incorporate and involve the community at large in the ongoing care and management of the child/youth with acquired brain injury while supporting the family. It also includes the ideas of continuity, accessibility, knowledge, collaboration, empowerment, and advocacy""[12]

The program also provides families with information about PABI, and what they should expect over the following couple of months. The PABICOP provides the families with packages of how to cope with the different symptoms the child may display, and some useful suggestions. Unfortunately, sometimes program leaders give parents the heart-breaking news that their child may never return to how they were before in some aspects. "The Pediatric Acquired Brain Injury Community Outreach Program (PABICOP) – An innovative comprehensive model of care for children and youth with an acquired brain injury"[12]

References

- 1 2 Toledo, E; Lebel, A; Becerra, L; Minster, A; Linnman, C; Maleki, N; Dodick, DW; Borsook, D (July 2012). "The young brain and concussion: imaging as a biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis.". Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 36 (6): 1510–31. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.007. PMC 3372677

. PMID 22476089.

. PMID 22476089. - 1 2 3 Bauer, R; Fritz, H (October 2004). "Pathophysiology of traumatic injury in the developing brain: an introduction and short update.". Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 56 (1-2): 65–73. doi:10.1016/j.etp.2004.04.002. PMID 15581277.

- ↑ Keightley, ML; Sinopoli, KJ; Davis, KD; Mikulis, DJ; Wennberg, R; Tartaglia, MC; Chen, JK; Tator, CH (2014). "Is there evidence for neurodegenerative change following traumatic brain injury in children and youth? A scoping review.". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 139. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00139. PMID 24678292.

- ↑ Keightley, Michelle (March 2014). "Is there evidence for neurodegenerative change following Traumatic Brain Injury in children and youth? A scoping review". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8 (139): 1=6. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00139. PMID 24678292.

- ↑ Li, Liu (January 2013). "The effect of pediatric traumatic brain injury on behavioral outcomes: a systematic review". Dev Med Child Neurol. 55 (1): 37=45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04414.x. PMID 22998525.

- ↑ Bloom, DR (May 2001). "Lifetime and novel psychiatric disorders after pediatric traumatic brain injury". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 40 (5): 572=579. doi:10.1097/00004583-200105000-00017. PMID 11349702.

- ↑ Yeates, KO (June 2005). "Long-term attention problems in children with traumatic brain injury". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 44 (6): 574=584. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000159947.50523.64. PMID 15908840.

- 1 2 3 Max JE (January 2014). "Neuropsychiatry of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury". Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 37 (1): 125–140. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2013.11.003.

- 1 2 3 Babikian T, Asarnow R (May 2009). "Neurocognitive outcomes and recovery after pediatric TBI: meta-analytic review of the literature". Neuropsychology. 23 (3): 283–96. doi:10.1037/a0015268. PMC 4064005

. PMID 19413443.

. PMID 19413443. - 1 2 Sohlberg, Mckay; MacPherson, Holly; Wade, Shari (2014). "A Pilot Study Evaluating Attention And Strategy Training Following Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury": 2, 5, 6, 7.

- 1 2 3 Cole, Wesley; Paulos, Stephanie (2009). "A Review of Family Intervention Guidelines for Pediatric Acquired Brain Injuries": 2, 5, 6.

- 1 2 3 Gillett, Jane (2004). "The Pediatri Acquired Brain Injury Community Outreach Program (PABICOP)": 3, 4.