Paris Commune

| Paris Commune | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A barricade on Rue Voltaire, after its capture by the regular army during the Bloody Week | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 170,000[1] | On paper, 200,000; in reality, probably between 25,000 and 50,000 actual combatants[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 877 killed, 6,454 wounded, and 183 missing[3] | 6,667 confirmed killed and buried.[4] Unconfirmed estimates between 10,000[5] and 20,000[6] killed | ||||||

The Paris Commune (French: La Commune de Paris, IPA: [la kɔmyn də paʁi]) was a radical socialist and revolutionary government that ruled Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871. Following the defeat of Emperor Napoleon III in September 1870, the French Second Empire swiftly collapsed. In its stead rose a Third Republic at war with Prussia, which laid siege to Paris for four months. A hotbed of working-class radicalism, France's capital was primarily defended during this time by the often politicized and radical troops of the National Guard rather than regular Army troops. In February 1871 Adolphe Thiers, the new chief executive of the French national government, signed an armistice with Prussia that disarmed the Army but not the National Guard.

Soldiers of the Commune's National Guard killed two French army generals, and the Commune refused to accept the authority of the French government. The regular French Army suppressed the Commune during "La semaine sanglante" ("The Bloody Week") beginning on 21 May 1871.[7] Debates over the policies and outcome of the Commune had significant influence on the ideas of Karl Marx, who described it as an example of the "dictatorship of the proletariat".[8]

Prelude

On 2 September 1870, after France's unexpected defeat at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War, Emperor Napoleon III surrendered to the Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. When the news reached Paris the next day, shocked and angry crowds came out into the streets. Empress Eugénie de Montijo, the Emperor's regent, fled the city, and the Government of the Second Empire swiftly collapsed. Republican and radical deputies of the National Assembly went to the Hôtel de Ville, proclaimed the new French Republic, and formed a Government of National Defense. Though the Emperor and the French Army had been defeated at Sedan, the war continued. The German army marched swiftly toward Paris.

Demographics

In 1871 France was deeply divided between the large rural, Catholic and conservative population of the French countryside and the more republican and radical cities of Paris, Marseille, Lyon and a few others. In the first round of the 1869 parliamentary elections held under the French Empire, 4,438,000 had voted for the Bonapartist candidates supporting Louis Napoleon III, while 3,350,000 had voted for the republican opposition. In Paris, however, the republican candidates dominated, winning 234,000 votes against 77,000 for the Bonapartists.[9]

Of the 2 million people in Paris in 1869, according to the official census, there were about 500,000 industrial workers, or fifteen percent of all the industrial workers in France, plus another 300,000-400,000 workers in other enterprises. Only about 40,000 were employed in factories and large enterprises; most were employed in small industries in textiles, furniture and construction. There were also 115,000 servants and 45,000 concierges. In addition to the native French population, there were about 100,000 immigrant workers and political refugees, the largest number being from Italy and Poland.[9]

During the war and the siege of Paris, various members of the middle- and upper-classes departed the city; at the same time there was an influx of refugees from parts of France occupied by the Germans. The working class and immigrants suffered the most from the lack of industrial activity due to the war and the siege; they formed the bedrock of the Commune's popular support.[9]

Radicalization of the Paris workers

The Commune resulted in part from growing discontent among the Paris workers.[10] This discontent can be traced to the first worker uprisings, the Canut Revolts, in Lyon and Paris in the 1830s[11] (a Canut was a Lyonnais silk worker, often working on Jacquard looms). Many Parisians, especially workers and the lower-middle classes, supported a democratic republic. A specific demand was that Paris should be self-governing with its own elected council, something enjoyed by smaller French towns but denied to Paris by a national government wary of the capital's unruly populace. They also wanted a more "just" way of managing the economy, if not necessarily socialist, summed up in the popular appeal for "la république démocratique et sociale!" ("the democratic and social republic!").

Socialist movements, such as the First International, had been growing in influence with hundreds of societies affiliated to it across France. In early 1867, Parisian employers of bronze-workers attempted to de-unionize their workers. This was defeated by a strike organized by the International. Later in 1867, an illegal public demonstration in Paris was answered by the legal dissolution of its executive committee and the leadership being fined. Tensions escalated: Internationalists elected a new committee and put forth a more radical program, the authorities imprisoned their leaders, and a more revolutionary perspective was taken to the International's 1868 Brussels Congress. The International had considerable influence even among unaffiliated French workers, particularly in Paris and the big towns.[12]

The killing of journalist Victor Noir incensed Parisians, and the arrests of journalists critical of the Emperor did nothing to quiet the city. A coup was attempted in early 1870, but tensions eased significantly after the plebiscite in May. The war with Prussia, initiated by Napoleon III in July, was initially met with patriotic fervour.[13]

Radicals and revolutionaries

Paris is the traditional home of French radical movements. Revolutionaries had gone into the streets to oppose their governments during the 1789 French Revolution, the popular uprisings of July 1830 and June 1848; all were violently repressed by the government.

Of the radical and revolutionary groups in Paris at the time of the Commune, the most conservative were the "radical republicans". This group included the young doctor and future Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, who was a member of the National Assembly and Mayor of the 18th arrondissement. Clemenceau tried to negotiate a compromise between the Commune and the government, but neither side trusted him; he was considered extremely radical by the provincial deputies of rural France, but too moderate by the leaders of the Commune.

The most extreme revolutionaries in Paris were the followers of Louis Auguste Blanqui, a charismatic professional revolutionary who had spent most of his adult life in prison. He had about a thousand followers, many of them armed and organized into cells of ten persons each. Each cell operated independently and was unaware of the members of the other groups, communicating only with their leaders by code. Blanqui had written a manual on revolution, Instructions for an Armed Uprising, to give guidance to his followers. Though their numbers were small, the Blanquists provided many of the most disciplined soldiers and several of the senior leaders of the Commune.

Defenders of Paris

By 20 September 1870, the German army had surrounded Paris and was camped just 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) from the French front lines. The regular French Army in Paris, under General Trochu's command, had only 50,000 professional soldiers of the line; the majority of the French first-line soldiers were prisoners of war, or trapped in Metz, surrounded by Germans. The regulars were thus supported by around 5,000 firemen, 3,000 gendarmes, and 15,000 sailors.[14] The regulars were also supported by the Garde Mobile, new recruits with little training or experience. 17,000 of them were Parisian, and 73,000 from the provinces. These included twenty battalions of men from Brittany, who spoke little French.[14]

The largest armed force in Paris was the Garde Nationale, or National Guard, numbering about 300,000 men. They also had very little training or experience. They were organized by neighborhoods; those from the upper- and middle-class arrondissements tended to support the national government, while those from the working-class neighborhoods were far more radical and politicized. Guardsmen from many units were known for their lack of discipline; some units refused to wear uniforms, often refused to obey orders without discussing them, and demanded the right to elect their own officers. The members of the National Guard from working-class neighborhoods became the main armed force of the Commune.[14]

Siege of Paris; first demonstrations

As the Germans surrounded the city, radical groups saw that the Government of National Defense had few soldiers to defend itself, and launched the first demonstrations against it. On 19 September, National Guard units from the main working-class neighborhoods—Belleville, Menilmontant, La Villette, Montrouge, the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and the Faubourg du Temple—marched to the centre of the city and demanded that a new government, a Commune, be elected. They were met by regular army units loyal to the Government of National Defense, and the demonstrators eventually dispersed peacefully. On 5 October, 5,000 protesters marched from Belleville to the Hotel de Ville, demanding immediate municipal elections and rifles. On 8 October, several thousand soldiers from the National Guard, led by Eugène Varlin of the First International, marched to the centre chanting 'Long Live the Commune!", but they also dispersed without incident.

Later in October, General Louis Jules Trochu launched a series of armed attacks to break the German siege, with heavy losses and no success. The telegraph line connecting Paris with the rest of France had been cut by the Germans on 27 September. On 6 October, Defense Minister Léon Gambetta departed the city by balloon to try to organise national resistance against the Germans.[15]

Uprising of 31 October

On 28 October, the news arrived in Paris that the 160,000 soldiers of the French army at Metz, which had been surrounded by the Germans since August, had surrendered. The news arrived the same day of the failure of another attempt by the French army to break the siege of Paris at Bourget, with heavy losses. On 31 October, the leaders of the main revolutionary groups in Paris, including Blanqui, Félix Pyat and Louis Charles Delescluze, called new demonstrations at the Hotel de Ville against General Trochu and the government. Fifteen thousand demonstrators, some of them armed, gathered in front of the Hôtel de Ville in pouring rain, calling for the resignation of Trochu and the proclamation of a commune. Shots were fired from the Hôtel de Ville, one narrowly missing Trochu, and the demonstrators crowded into the building, demanding the creation of a new government, and making lists of its proposed members.[16]

Blanqui, the leader of the most radical faction, established his own headquarters at the nearby Prefecture of the Seine, issuing orders and decrees to his followers, intent upon establishing his own government. While the formation of the new government was taking place inside the Hôtel de Ville, however, units of the National Guard and Garde Mobile loyal to General Trochu arrived and recaptured the building without violence. By three o'clock, the demonstrators had been given safe passage and left, and the brief uprising was over.[16]

On 3 November, city authorities organized a plebiscite of Parisian voters, asking if they had confidence in the Government of National Defense. "Yes" votes totalled 557,996, while 62,638 voted "no". Two days later, municipal councils in each of the twenty arrondissements of Paris voted to elect mayors; five councils elected radical opposition candidates, including Delescluze and a young Montmartrean doctor, Georges Clemenceau.[17]

Negotiations with the Germans; continued war

In September and October Adolphe Thiers, the leader of the National Assembly conservatives, had toured Europe, consulting with the foreign ministers of Britain, Russia, and Austria, and found that none of them were willing to support France against the Germans. He reported to the Government that there was no alternative to negotiating an armistice. He travelled to German-occupied Tours and met with Bismarck on 1 November. The Chancellor demanded the cession of all of Alsace, parts of Lorraine, and enormous reparations. The Government of National Defense decided to continue the war and raise a new army to fight the Germans. The newly organized French armies won a single victory at Coulmiers on 10 November, but an attempt by General Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot on 29 November at Villiers to break out of Paris was defeated with a loss of 4,000 soldiers, compared with 1,700 German casualties.

Everyday life for Parisians became increasingly difficult during the siege. In December temperatures dropped to −15 °C (5 °F), and the Seine froze for three weeks. Parisians suffered shortages of food, firewood, coal and medicine. The city was almost completely dark at night. The only communication with the outside world was by balloon, carrier pigeon, or letters packed in iron balls floated down the Seine. Rumors and conspiracy theories abounded. Because supplies of ordinary food ran out, starving denizens ate most of the city zoo's animals, and then having eaten those, Parisians resorted to feeding on rats.

By early January 1871, Bismarck and the Germans themselves were tired of the prolonged siege. They installed seventy-two 120- and 150-mm artillery pieces in the forts around Paris and on 5 January began to bombard the city day and night. Between 300 and 600 shells hit the center of the city every day.[18]

Uprising and armistice

Between 11 and 19 January 1871, the French armies had been defeated on four fronts and Paris was facing a famine. General Trochu received reports from the prefect of Paris that agitation against the government and military leaders was increasing in the political clubs and in the National Guard of Belleville, La Chapelle, Montmartre, and Gros-Caillou.

At midday on 22 January, three or four hundred National Guards and members of radical groups – mostly Blanquists – gathered outside the Hôtel de Ville. A battalion of Gardes Mobiles from Brittany was inside the building to defend it in case of an assault. The demonstrators presented their demands that the military be placed under civil control, and that there be an immediate election of a commune. The atmosphere was tense, and in the middle of the afternoon, gunfire broke out between the two sides; each side blamed the other for firing first. Six demonstrators were killed, and the army cleared the square. The government quickly banned two publications, Le Reveil of Delescluze and Le Combat of Pyat, and arrested 83 revolutionaries.

At the same time as the demonstration in Paris, the leaders of the Government of National Defense in Bordeaux, had concluded that the war could not continue. On 26 January, they signed a ceasefire and armistice, with special conditions for Paris. The city would not be occupied by the Germans. Regular soldiers would give up their arms, but would not be taken into captivity. Paris would pay an indemnity of 200 million francs. At Jules Favre's request, Bismarck agreed not to disarm the National Guard, so that order could be maintained in the city.

Adolphe Thiers; parliamentary elections of 1871

The national government in Bordeaux called for national elections at the end of January, held just ten days later on 8 February. Most electors in France were rural, Catholic and conservative, and this was reflected in the results; of the 645 deputies assembled in Bordeaux on February, about 400 favoured a constitutional monarchy under either Henri, Count of Chambord (grandson of Charles X) or Prince Philippe, Count of Paris (grandson of Louis Philippe).[19]

Of the 200 republicans in the new parliament, 80 were former Orleanists (Henri's supporters) and moderately conservative. They were led by Adolphe Thiers, who was elected in 26 departments, the most of any candidate. There were an equal number of more radical republicans, including Jules Favre and Jules Ferry, who wanted a republic without a monarch, and who felt that signing the peace treaty was unavoidable. Finally, on the extreme left, there were the radical republicans and socialists, a group that included Louis Blanc, Léon Gambetta and Georges Clemenceau. This group was dominant in Paris, where they won 37 of the 42 seats.[20]

On 17 February the new Parliament elected the 74-year-old Thiers as chief executive of the French Third Republic. He was considered to be the candidate most likely to bring peace and to restore order. For long an opponent of the Prussian war, Thiers persuaded Parliament that peace was necessary. He travelled to Versailles, where Bismarck and the German King were waiting, and on 24 February the armistice was signed.

Establishment

Dispute over cannons of Paris

At the end of the war 400 obsolete muzzle-loading bronze cannons, partly paid for by the Paris public via a subscription, remained in the city. The new Central Committee of the National Guard, now dominated by radicals, decided to put the cannons in parks in the working-class neighborhoods of Belleville, Buttes-Chaumont and Montmartre, to keep them away from the regular army and to defend the city against any attack by the national government. Thiers was equally determined to bring the cannons under national-government control.

Clemenceau, a friend of several revolutionaries, tried to negotiate a compromise; some cannons would remain in Paris and the rest go to the army. However, Thiers and the National Assembly did not accept his proposals. The chief executive wanted to restore order and national authority in Paris as quickly as possible, and the cannons became a symbol of that authority. The Assembly also refused to prolong the moratorium on debt collections imposed during the war; and suspended two radical newspapers, Le Cri du Peuple of Jules Valles and Le Mot d'Ordre of Henri Rochefort, which further inflamed Parisian radical opinion. Thiers also decided to move the National Assembly and government from Bordeaux to Versailles, rather than to Paris, to be farther away from the pressure of demonstrations, which further enraged the National Guard and the radical political clubs.[21]

On 17 March 1871, there was a meeting of Thiers and his cabinet, who were joined by Paris mayor Jules Ferry, National Guard commander General D'Aurelle de Paladines and General Joseph Vinoy, commander of the regular army units in Paris. Thiers announced a plan to send the army the next day to take charge of the cannons. The plan was initially opposed by War Minister Adolphe Le Flô, D'Aurelle de Paladines, and Vinoy, who argued that the move was premature, because the army had too few soldiers, was undisciplined and demoralized, and that many units had become politicized and were unreliable. Vinoy urged that they wait until Germany had released the French prisoners of war, and the army returned to full strength. Thiers insisted that the planned operation must go ahead as quickly as possible, to have the element of surprise. If the seizure of the cannon was not successful, the government would withdraw from the center of Paris, build up its forces, and then attack with overwhelming force, as they had done during the uprising of June 1848. The Council accepted his decision, and Vinoy gave orders for the operation to begin the next day.[22]

Failed seizure attempt and government retreat

.jpg)

Early in the morning of 18 March, two brigades of soldiers climbed the butte of Montmartre, where the largest collection of cannons, 170 in number, were located. A small group of revolutionary national guardsmen were already there, and there was a brief confrontation between the brigade led by General Claude Lecomte, and the National Guard; one guardsman, named Turpin, was shot dead. Word of the shooting spread quickly, and members of the National Guard from all over the neighborhood, including Clemenceau, hurried to the site to confront the soldiers.

Elsewhere in Paris, the Army had succeeded in securing the cannons at Belleville and Buttes-Chaumont and other strategic points; but a crowd gathered and continued to grow, and the situation grew increasingly tense at Montmartre. The horses that were needed to move the cannon away did not arrive, and the army units were immobilized. As the soldiers were surrounded by the crowd, they began to break ranks and join the crowd. General Lecomte tried to withdraw, and then ordered his soldiers to load their weapons and fix bayonets. He thrice ordered them to fire, but the soldiers refused. Some of the officers were disarmed and taken to the city hall of Montmartre, under the protection of Clemenceau. General Lecomte and the officers of his staff were seized by the guardsmen and his mutinous soldiers and taken to the local headquarters of the National Guard at the ballroom of the Chateau-Rouge. The officers were pelted with rocks, struck, threatened, and insulted by the crowd. In the middle of the afternoon Lecomte and the other officers were taken to 6 Rue des Rosiers by members of a group calling themselves The Committee of Vigilance of the 18th arrondissement, who demanded that they be tried and executed.[23]

At 5:00 in the afternoon, the National Guard had captured another important prisoner: General Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas. An ardent republican and fierce disciplinarian, he had helped suppress the armed uprising of June 1848 against the Second Republic. Because of his republican beliefs, he had been arrested by Napoleon III and exiled, and had only returned to France after the downfall of the Empire. He was particularly hated by the national guardsmen of Montmartre and Belleville because of the severe discipline he imposed during the siege of Paris.[24] Earlier that day, dressed in civilian clothes, he had been trying to find out what was going on, when he was recognized by a soldier and arrested, and brought to the building at Rue des Rosiers. At about 5:30 on 18 March, the angry crowd of national guardsmen and deserters from Lecomte's regiment at Rue des Rosiers seized Clément-Thomas, beat him with rifle butts, pushed him into the garden, and shot him repeatedly. A few minutes later, they did the same to General Lecomte. Doctor Guyon, who examined the bodies shortly afterwards, found forty balls in the body of Clément-Thomas and nine balls in the back of Lecomte.[25][26] By late morning, the operation to recapture the cannons had failed, and crowds and barricades were appearing in all the working-class neighborhoods of Paris. General Vinoy ordered the army to pull back to the Seine, and Thiers began to organise a withdrawal to Versailles, where he could gather enough troops to take back Paris.

On the afternoon of 18 March, following the government's failed attempt to seize the cannons at Montmartre, the Central Committee of the National Guard ordered the three battalions to seize the Hôtel de Ville, where they believed the government was located. They were not aware that Thiers, the government, and the military commanders were at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where the gates were open and there were few guards. They were also unaware that Marshal Patrice MacMahon, the future commander of the forces against the Commune, had just arrived at his home in Paris, having just been released from imprisonment in Germany. As soon as he heard the news of the uprising, he made his way to the train station, where national guardsmen were already stopping and checking the identity of departing passengers. A sympathetic station manager hid him in his office and helped him board a train, and he escaped the city. While he was at the train station, national guardsmen sent by the Central Committee arrived at his house looking for him.[27][28]

On the advice of General Vinoy, Thiers ordered the evacuation to Versailles of all the regular forces in Paris, some forty thousand soldiers, including the soldiers in the fortresses around the city; the regrouping of all the army units in Versailles; and the departure of all government ministries from the city.

National Guard takes power

In February, while the national government had been organising in Bordeaux, a new rival government had been organized in Paris. The National Guard had not been disarmed as per the armistice, and had on paper 260 battalions of 1,500 men each, a total of 390,000 men.[29] Between 15 and 24 February, some 500 delegates elected by the National Guard began meeting in Paris. On 15 March, just before the confrontation between the National Guard and the regular army over the cannons, 1,325 delegates of the federation of organizations created by the National Guard elected a leader, Giuseppe Garibaldi (who was in Italy and respectfully declined the title), and created a Central Committee of 38 members, which made its headquarters in a school on the Rue Basfroi, between Place de la Bastille and La Roquette. The first vote of the new Central Committee was to refuse to recognise the authority of General D'Aurelle de Paladines, the official commander of the National Guard appointed by Thiers, or of General Vinoy, the Military Governor of Paris.[30]

Late on 18 March, when they learned that the regular army was leaving Paris, units of the National Guard moved quickly to take control of the city. The first to take action were the followers of Blanqui, who went quickly to the Latin Quarter and took charge of the gunpowder stored in the Pantheon, and to the Orleans train station. Four battalions crossed the Seine and captured the prefecture of police, while other units occupied the former headquarters of the National Guard at the Place Vendôme, as well as the Ministry of Justice. That night, the National Guard occupied the offices vacated by the government; they quickly took over the Ministries of Finance, the Interior, and War. At eight in the morning the next day, the Central Committee was meeting in the Hôtel de Ville. By the end of the day, 20,000 national guardsmen camped in triumph in the square in front of the Hôtel de Ville, with several dozen cannons. A red flag was hoisted over the building.[31]

The extreme-left members of the Central Committee, led by the Blanquists, demanded an immediate march on Versailles, to disperse the Thiers government and to impose their authority on all of France; but the majority first wanted to establish a more solid base of legal authority in Paris. The Committee officially lifted the state of siege, named commissions to administer the government, and called elections for 23 March. They also sent a delegation of mayors of the Paris arrondissements, led by Clemenceau, to negotiate with Thiers in Versailles to obtain a special independent status for Paris.

Council elections

In Paris, hostility was growing between the elected republican mayors, including Clemenceau, who believed that they were legitimate leaders of Paris, and the Central Committee of the National Guard.[32] On 22 March, the day before the elections, the Central Committee declared that it, not the mayors, was the legitimate government of Paris.[33] It declared that Clemenceau was no longer the Mayor of Montmartre, and seized the city hall there, as well as the city halls of the 1st and 2nd arrondissements, which were occupied by more radical national guardsmen. "We are caught between two bands of crazy people," Clemenceau complained, "those sitting in Versailles and those in Paris."

The elections of 26 March elected a Commune council of 92 members, one for every twenty thousand residents. Ahead of the elections, the Central Committee and the leaders of the International gave out their lists of candidates; mostly belonging to the extreme left. The candidates had only a few days to campaign. Thiers' government in Versailles urged Parisians to abstain from voting. When the voting was finished, 233,000 Parisians had voted, out of 485,000 registered voters, or forty-eight percent. In upper-class neighborhoods many abstained from voting: 77 percent of voters in the 7th and 8th arrondissements; 68 percent in the 15th, 66 percent in the 16th, and 62 percent in the 6th and 9th. But in the working-class neighborhoods, turnout was high: 76 percent in the 20th arrondissement, 65 percent in the 19th, and 55 to 60 percent in the 10th, 11th, and 12th.[34]

A few candidates, including Blanqui (who had been arrested when outside Paris, and was in prison in Brittany), won in several arrondissements. Other candidates who were elected, including about twenty moderate republicans and five radicals, refused to take their seats. In the end, the Council had just 60 members. Nine of the winners were Blanquists (some of whom were also from the International); twenty-five, including Delescluze and Pyat, classified themselves as "Independent Revolutionaries"; about fifteen were from the International; the rest were from a variety of radical groups. One of the best-known candidates, George Clemenceau, received only 752 votes. The professions represented in the council were 33 workers; five small businessmen; 19 clerks, accountants and other office staff; twelve journalists; and a selection of workers in the liberal arts. All were men; women were not allowed to vote.[35] The winners were announced on 27 March, and a large ceremony and parade by the National Guard was held the next day in front of the Hôtel de Ville, decorated with red flags.

Organization and early work

The new Commune held its first meeting on 28 March in a euphoric mood. The members adopted a dozen proposals, including an honorary presidency for Blanqui; the abolition of the death penalty; the abolition of military conscription; a proposal to send delegates to other cities to help launch communes there; and a resolution declaring that membership in the Paris Commune was incompatible with being a member of the National Assembly. This was aimed particularly at Pierre Tirard, the republican mayor of the 2nd arrondissement, who had been elected to both Commune and National Assembly. Seeing the more radical political direction of the new Commune, Tirard and some twenty republicans decided it was wisest to resign from the Commune. A resolution was also passed, after a long debate, that the deliberations of the Council were to be secret, since the Commune was effectively at war with the government in Versailles and should not make its intentions known to the enemy.[36]

Following the model proposed by the more radical members, the new government had no president, no mayor, and no commander in chief. The Commune began by establishing nine commissions, similar to those of the National Assembly, to manage the affairs of Paris. The commissions in turn reported to an Executive Commission. One of the first measures passed declared that military conscription was abolished, that no military force other than the National Guard could be formed or introduced into the capital, and that all healthy male citizens were members of the National Guard. The new system had one important weakness: the National Guard now had two different commanders. They reported to both the Central Committee of the National Guard and to the Executive Commission, and it was not clear which one was in charge of the inevitable war with Thiers' government.[37]

Administration and actions

Program

The Commune adopted the discarded French Republican Calendar during its brief existence and used the socialist red flag rather than the republican tricolor. Despite internal differences, the Council began to organise the public services essential for a city of two million residents. It also reached a consensus on certain policies that tended towards a progressive, secular, and highly democratic social democracy. Because the Commune met on fewer than sixty days in all, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included:

- separation of church and state;

- remission of rents owed for the entire period of the siege (during which payment had been suspended);

- abolition of night work in bakeries;

- granting of pensions to the unmarried companions and children of national guardsmen killed in active service;

- free return by pawnshops, of all workmen's tools and household items, valued up to 20 francs, pledged during the siege;

- postponement of commercial debt obligations, and the abolition of interest on the debts;

- right of employees to take over and run an enterprise if it were deserted by its owner; the Commune, nonetheless, recognized the previous owner's right to compensation;

- prohibition of fines imposed by employers on their workmen.[38]

The decrees separated the church from the state, appropriated all church property to public property, and excluded the practice of religion from schools. In theory, the churches were allowed to continue their religious activity only if they kept their doors open for public political meetings during the evenings. In practice, many churches were closed, and many priests were arrested and held as hostages, in the hope of trading them for Blanqui, imprisoned in Brittany since 17 March.[39]

The workload of the Commune leaders was usually enormous. The Council members (who were not "representatives" but delegates, subject in theory to immediate recall by their electors) were expected to carry out many executive and military functions as well as their legislative ones. Numerous organizations were set up during the siege in the localities (quartiers) to meet social needs, such as canteens and first-aid stations. For example, in the 3rd arrondissement, school materials were provided free, three parochial schools were "laicised", and an orphanage was established. In the 20th arrondissement, schoolchildren were provided with free clothing and food. At the same time, these local assemblies pursued their own goals, usually under the direction of local workers. Despite the moderate reformism of the Commune council, the composition of the Commune as a whole was much more revolutionary. Revolutionary factions included Proudhonists (an early form of moderate anarchism), members of the international socialists, Blanquists, and more libertarian republicans.

Feminist initiatives

Women played an important role in both the initiation and the governance of the Commune, including active participation in building barricades and caring for wounded fighters.[40] Joséphine Marchias, a washer woman, picked up a gun during the battles of May 22-23rd and said, "You cowardly crew! Go and Fight! If I'm killed it will be because I've done some killing first!" She was arrested as an incendiary, but there is no documentation that she was a pétroleuse (female incendiary). She worked as a vivandiére with the Enfants Perdus. While carrying back the laundry she was given by the guardsmen, she carried away the body of her lover, Jean Guy, who was a butcher's apprentice.[40][41] There were reports in various newspapers of pétroleuses but evidence remains weak. The Paris Journal reported that soldiers arrested 13 women who allegedly threw petrol into houses. There were rumors that pétroleuses were paid 10 francs per house. While clear that Communards set some of the fires, the reports of women participating in it was overly exaggerated at the time.[42] Several women and children threw themselves between Thiers' army and the cannons they were attempting to confiscate from Montmartre. Despite orders from their commanders, some soldiers refused to fire on their own people.

Some women organized a feminist movement, following earlier attempts in 1789 and 1848. Thus, Nathalie Lemel, a socialist bookbinder, and Élisabeth Dmitrieff, a young Russian exile and member of the Russian section of the First International, created the Women's Union for the Defense of Paris and Care of the Wounded on 11 April 1871. The feminist writer André Léo, a friend of Paule Minck, was also active in the Women's Union. Believing that their struggle against patriarchy could only be pursued through a global struggle against capitalism, the association demanded gender and wage equality, the right of divorce for women, the right to secular education, and professional education for girls. They also demanded suppression of the distinction between married women and concubines, and between legitimate and illegitimate children. They advocated the abolition of prostitution (obtaining the closing of the maisons de tolérance, or legal brothels). The Women's Union also participated in several municipal commissions and organized cooperative workshops.[43] Along with Eugène Varlin, Nathalie Le Mel created the cooperative restaurant La Marmite, which served free food for indigents, and then fought during the Bloody Week on the barricades.[44]

Paule Minck opened a free school in the Church of Saint Pierre de Montmartre and animated the Club Saint-Sulpice on the Left Bank.[44] The Russian Anne Jaclard, who declined to marry Dostoyevsky and finally became the wife of Blanquist activist Victor Jaclard, founded the newspaper Paris Commune with André Léo. She was also a member of the Comité de vigilance de Montmartre, along with Louise Michel and Paule Minck, as well as of the Russian section of the First International. Victorine Brocher, close to the IWA activists, and founder of a cooperative bakery in 1867, also fought during the Commune and the Bloody Week.[44] Famous figures such as Louise Michel, the "Red Virgin of Montmartre", who joined the National Guard and would later be sent to New Caledonia, symbolized the active participation of a small number of women in the insurrectionary events. A female battalion from the National Guard defended the Place Blanche during the repression.

Bank of France

The Commune named Francis Jourde as the head of the Commission of Finance. A former clerk of a notary, accountant in a bank and employee of the city's bridges and roads department, Jourde maintained the Commune's accounts with prudence. Paris's tax receipts amounted to 20 million francs, with another 6 million seized at the Hotel de Ville. The expenses of the Commune were 42 million, the largest part going to pay the daily salary of the National Guard. Jourde first obtained a loan from the Rothschild Bank, then paid the bills from the city account, which was soon exhausted.

The gold reserves of the Bank of France had been moved out of Paris for safety in August 1870, but its vaults contained 88 million francs in gold coins and 166 million francs in banknotes. When the Thiers government left Paris in March, they did not have the time or the reliable soldiers to take the money with them. The reserves were guarded by 500 national guardsmen who were themselves Bank of France employees. Some Communards wanted to appropriate the bank's reserves to fund social projects, but Jourde resisted, explaining that without the gold reserves the currency would collapse and all the money of the Commune would be worthless. The Commune appointed Charles Beslay as the Commissaire of the Bank of France, and he arranged for the Bank to loan the Commune 400,000 francs a day. This was approved by Thiers, who felt that to negotiate a future peace treaty the Germans were demanding war reparations of five billion francs; the gold reserves would be needed to keep the franc stable and pay the indemnity. Jourde's prudence was later condemned by Karl Marx and other Marxists, who felt the Commune should have confiscated the bank's reserves and spent all the money immediately.[45]

Press

From 21 March, the Central Committee of the National Guard banned the major pro-Versailles newspapers, Le Gaulois and Le Figaro. Their offices were invaded and closed by crowds of the Commune's supporters. After 18 April other newspapers sympathetic to Versailles were also closed. The Versailles government, in turn, imposed strict censorship and prohibited any publication in favour of the Commune.

At the same time, the number of pro-Commune newspapers and magazines published in Paris during the Commune expanded exponentially. The most popular of the pro-Commune newspapers was Le Cri du Peuple, published by Jules Valles, which was published from 22 February until 23 May. Another highly popular publication was Le Père Duchêne, inspired by a similar paper of the same name published from 1790 until 1794; after its first issue on 6 March, it was briefly closed by General Vinoy, but it reappeared until 23 May. It specialized in humour, vulgarity and extreme abuse against the opponents of the Commune.[46]

A republican press also flourished, including such papers as Le Mot d'Ordre of Henri Rochefort, which was both violently anti-Versailles and critical of the faults and excesses of the Commune. The most popular republican paper was Le Rappel, which condemned both Thiers and the killing of generals Lecomte and Clement-Thomas by the Communards. Its editor Auguste Vacquerie was close to Victor Hugo, whose son wrote for the paper. The editors wrote, "We are against the National Assembly, but we are not for the Commune. That which we defend, that which we love, that which we admire, is Paris."[47]

Catholic Church

From the beginning, the Commune had a tense relationship with the Catholic Church. On 2 April, soon after the Commune was established, it voted a decree accusing the Catholic Church of "complicity in the crimes of the monarchy." The decree declared the separation of church and state, confiscated the state funds allotted to the Church, seized the property of religious congregations, and ordered that Catholic schools cease religious education and become secular. Over the next seven weeks, some two hundred priests, nuns and monks were arrested, and twenty-six churches were closed to the public. At the urging of the more radical newspapers, National Guard units searched the basements of churches, looking for evidence of alleged sadism and criminal practices. More extreme elements of the National Guard carried out mock religious processions and parodies of religious services. Early in May, some of the political clubs began to demand the immediate execution of Archbishop Darboy and the other priests in the prison. The Archbishop and a number of priests were executed during Bloody Week, in retaliation for the execution of Commune soldiers by the regular army.[48]

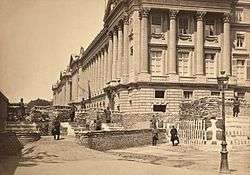

Destruction of the Vendôme Column

The destruction of the Vendôme Column honouring the victories of Napoleon I, topped by a statue of the Emperor, was one of the most prominent civic events during the Commune. It was voted on 12 April by the executive committee of the Commune, which declared that the column was "a monument of barbarism" and a "symbol of brute force and false pride." The idea had originally come from the painter Gustave Courbet, who had written to the Government of National Defense on 4 September calling for the demolition of the column. In October, he had called for a new column, made of melted-down German cannons, "the column of peoples, the column of Germany and France, forever federated." Courbet was elected to the Council of the Commune on 16 April, after the decision to tear down the column had already been made. The ceremonial destruction took place on 16 May. In the presence of two battalions of the National Guard and the leaders of the Commune, a band played "La Marseillaise" and the "Chant du Départ". The first effort to pull down the column failed, but at 5:30 in the afternoon the column broke from its base and shattered into three pieces. The pedestal was draped with red flags, and pieces of the statue were taken to be melted down and made into coins.[49]

On 12 May another civic event took place: the destruction of Thiers' home on Place Saint-Georges. Proposed by Henri Rochefort, editor of the Le Mot d'Ordre, on 6 April, it had not been voted upon by the Commune until 10 May. According to the decree of the Commune, the works of art were to be donated to the Louvre (which refused them) and the furniture was to be sold, the money to be given to widows and orphans of the fighting. The house was emptied and destroyed on 12 May.[50]

War with the national government

Failure of the march on Versailles

In Versailles, Thiers had estimated that he needed 150,000 men to recapture Paris, and that he had only about 20,000 reliable first-line soldiers, plus about 5,000 gendarmes. He worked rapidly to assemble a new and reliable regular army. Most of the soldiers were prisoners of war who had just been released by the Germans, following the terms of the armistice. Others were sent from military units in all of the provinces. To command the new army, Thiers chose Patrice MacMahon, who had won fame fighting the Austrians in Italy under Napoleon III, and who had been seriously wounded at the Battle of Sedan. He was highly popular both within the army and in the country. By 30 March, less than two weeks after the Army's Montmartre rout, it began skirmishing with the National Guard in the outskirts of Paris.

In Paris, members of the Military Commission and the Executive Committee of the Commune, as well as the Central Committee of the National Guard, met on 1 April. They decided to launch an offensive against the Army in Versailles within five days. The attack was first launched on the morning of 2 April by five battalions who crossed the Seine at the Pont de Neuilly. The National Guard troops were quickly repulsed by the Army, with a loss of about twelve soldiers. One officer of the Versailles army, a surgeon from the medical corps, was killed; the National Guardsmen had mistaken his uniform for that of a gendarme. Five national guardsmen were captured by the regulars; two were Army deserters and two were caught with their weapons in their hands. General Vinoy, the commander of the Paris Military District, had ordered any prisoners who were deserters from the Army to be shot. The commander of the regular forces, Colonel Georges Ernest Boulanger, went further and ordered that all four prisoners be summarily shot. The practice of shooting prisoners captured with weapons became common in the bitter fighting in the weeks ahead.[51]

Despite this first failure, Commune leaders were still convinced that, as at Montmartre, French army soldiers would refuse to fire on national guardsmen. They prepared a massive offensive of 27,000 national guardsmen who would advance in three columns. They were expected to converge at the end of 24 hours at the gates of the Palace of Versailles. They advanced on the morning of 3 April—without cavalry to protect the flanks, without artillery, without stores of food and ammunition, and without ambulances—confident of rapid success. They passed by the line of forts outside the city, believing them to be occupied by national guardsmen. In fact the army had re-occupied the abandoned forts on 28 March. The National Guard soon came under heavy artillery and rifle fire; they broke ranks and fled back to Paris. Once again national guardsmen captured with weapons were routinely shot by army units.[52]

Decree on Hostages

Commune leaders responded to the execution of prisoners by the Army by passing a new order on 5 April—the Decree on Hostages. Under the decree, any person accused of complicity with the Versailles government could be immediately arrested, imprisoned and tried by a special jury of accusation. Those convicted by the jury would become "hostages of the people of Paris." Article 5 stated, "Every execution of a prisoner of war or of a partisan of the government of the Commune of Paris will be immediately followed by the execution of a triple number of hostages held by virtue of article four." Prisoners of war would be brought before a jury, which would decide if they would be released or held as hostages.[53]

Under the new decree, a number of prominent religious leaders were promptly arrested, including the Abbé Deguerry, the curé of the Madeleine church, and the archbishop of Paris Georges Darboy, who was confined at the Mazas prison. The National Assembly in Versailles responded to the decree the next day; it passed a law allowing military tribunals to judge and punish suspects within 24 hours. Émile Zola wrote, "Thus we citizens of Paris are placed between two terrible laws; the law of suspects brought back by the Commune and the law on rapid executions which will certainly be approved by the Assembly. They are not fighting with cannon shots, they are slaughtering each other with decrees."[54]

Radicalization

By April, as MacMahon's forces steadily approached Paris, divisions arose within the Commune about whether to give absolute priority to military defense, or to political and social freedoms and reforms. The majority, including the Blanquists and the more radical revolutionaries, supported by Le Vengeur of Pyat and Le Père Duchesne of Vermersch, supported giving the military priority. The publications La Commune, La Justice and Valles' Le Cri du Peuple feared that a more authoritarian government would destroy the kind of social republic they wanted to achieve. Soon, the Council of the Commune voted, with strong opposition, for the creation of a Committee of Public Safety, modelled on the eponymous Committee that carried out the Reign of Terror (1793–94). Because of the implications carried by its name, many members of the Commune opposed the Committee of Public Safety's creation.

The Committee was given extensive powers to hunt down and imprison enemies of the Commune. Led by Raoul Rigault, it began to make several arrests, usually on suspicion of treason, intelligence with the enemy, or insults to the Commune. Those arrested included General de Martimprey—almost 80 years old, the governor of the Invalides, alleged to having caused the assassination of revolutionaries in December 1851—as well as more recent commanders of the National Guard, including Cluseret. High religious officials had been arrested: Archbishop Darboy, the Vicar General Abbé Lagarde, and the Curé of the Madeleine Abbé Deguerry. The policy of holding hostages for possible reprisals was denounced by some defenders of the Commune, including Victor Hugo, in a poem entitled "No Reprisals" published in Brussels on 21 April.[55] On 12 April, Rigault proposed to exchange Archbishop Darboy and several other priests for the imprisoned Blanqui. Thiers refused the proposal. On 14 May, Rigault proposed to exchange 70 hostages for the extreme-left leader, and Thiers again refused.[56]

Composition of the National Guard

Since every able-bodied man in Paris was obliged to be a member of the National Guard, the Commune on paper had an army of about 200,000 men on 6 May; the actual number was much lower, probably between 25,000 and 50,000 men. At the beginning of May, 20 percent of the National Guard was reported absent without leave. The National Guard had hundreds of cannons and thousands of rifles in its arsenal, but only half of the cannons and two-thirds of the rifles were ever used. There were heavy naval cannons mounted on the ramparts of Paris, but few national guardsmen were trained to use them. Between the end of April and 20 May, the number of trained artillerymen fell from 5,445 to 2,340.[2]

The officers of the National Guard were elected by the soldiers, and their leadership qualities and military skills varied widely. Gustave Clusaret, the commander of the National Guard until his dismissal on 1 May, had tried to impose more discipline in the army, disbanding many unreliable units and making soldiers live in barracks instead of at home. He recruited officers with military experience, particularly Polish officers who had fled to France in 1863, after Russians crushed the January Uprising; they played a prominent role in the last days of the Commune.[57] One of these officers was General Jaroslav Dombrowski, a former Imperial Russian Army officer, who was appointed commander of the Commune forces on the right bank of the Seine. On 5 May, he was appointed commander of the Commune's whole army. Dombrowski held this position until 23 May, when he was killed while defending the city barricades.[58]

Capture of Fort Issy

One of the key strategic points around Paris was Fort Issy, south of the city near the Porte de Versailles, which blocked the route of the Army into Paris. The fort's garrison was commanded by Leon Megy, a former mechanic and a militant Blanquist, who had been sentenced to 20 years hard labour for killing a policeman. After being freed he had led the takeover of the prefecture of Marseille by militant revolutionaries. When he came back to Paris, he was given the rank of colonel by the Central Committee of the National Guard, and the command of Fort Issy on 13 April.

The army commander, General Ernest de Cissey, began a systematic siege and a heavy bombardment of the fort that lasted three days and three nights. At the same time Cissey sent a message to Colonel Megy, with the permission of Marshal MacMahon, offering to spare the lives of the fort's defenders, and let them return to Paris with their belongings and weapons, if they surrendered the fort. Colonel Megy gave the order, and during the night of 29–30 April, most of the soldiers evacuated the fort and returned to Paris. But news of the evacuation reached the Central Committee of the National Guard and the Commune. Before General Cissey and the Versailles army could occupy the fort, the National Guard rushed reinforcements there and re-occupied all the positions. General Cluseret, commander of the National Guard, was dismissed and put in prison. General Cissey resumed the intense bombardment of the fort. The defenders resisted until the night of 7–8 May, when the remaining national guardsmen in the fort, unable to withstand further attacks, decided to withdraw. The new commander of the National Guard, Louis Rossel, issued a terse bulletin: "The tricolor flag flies over the fort of Issy, abandoned yesterday by the garrison." The abandonment of the fort led the Commune to dismiss Rossel, and replace him with Delescluze, a fervent Communard but a journalist with no military experience.[59]

Bitter fighting followed, as MacMahon's army worked their way systematically forward to the walls of Paris. On 20 May, MacMahon's artillery batteries at Montretout, Mont-Valerian, Boulogne, Issy, and Vanves opened fire on the western neighborhoods of the city—Auteuil, Passy, and the Trocadero—with shells falling close to l'Étoile. Dombrowski reported that the soldiers he had sent to defend the ramparts of the city between Point du Jour and Porte d'Auteuil had retreated to the city; he had only 4,000 soldiers left at la Muette, 2,000 at Neuilly, and 200 at Asnieres and Saint Ouen. "I lack artillerymen and workers to hold off the catastrophe."[60] On 19 May, while the Commune executive committee was meeting to judge the former military commander Clauseret for the loss of the Issy fortress, it received word that the forces of Marshal MacMahon were within the fortifications of Paris.

"Bloody Week"

21 May: Army enters Paris

The final offensive on Paris by MacMahon's army began early in the morning on Sunday, 21 May. On the front line, soldiers learned from a sympathiser inside the walls that the National Guard had withdrawn from one section of the city wall at Point-du-Jour, and the fortifications were undefended. An army engineer crossed the moat and inspected the empty fortifications, and immediately telegraphed the news to Marshal MacMahon, who was with Thiers at Fort Mont-Valérien. MacMahon immediately gave orders, and two battalions passed through the fortifications without meeting anyone, and occupied the Porte de Saint-Cloud and the Porte de Versailles. By four o'clock in the morning, sixty thousand soldiers had passed into the city and occupied Auteuil and Passy.[61]

Once the fighting began inside Paris, the strong neighborhood loyalties that had been an advantage of the Commune became something of a disadvantage: instead of an overall planned defense, each "quartier" fought desperately for its survival, and each was overcome in turn. The webs of narrow streets that made entire districts nearly impregnable in earlier Parisian revolutions had in the center been replaced by wide boulevards during Haussmann's renovation of Paris. The Versailles forces enjoyed a centralized command and had superior numbers. They had learned the tactics of street fighting and simply tunnelled through the walls of houses to outflank the Communards' barricades.

The trial of Gustave Cluseret, the former commander, was still going on at the Commune when they received the message from General Dombrowski that the army was inside the city. He asked for reinforcements and proposed an immediate counterattack. "Remain calm," he wrote, "and everything will be saved. We must not be defeated!".[62] When they had received this news, the members of the Commune executive returned to their deliberations on the fate of Cluseret, which continued until eight o'clock that evening.

The first reaction of many of the National Guard was to find someone to blame, and Dombrowski was the first to be accused. Rumors circulated that he had accepted a million francs to give up the city. He was deeply offended by the rumors. They stopped when Dombrowski died two days later from wounds received on the barricades. His last reported words were: "Do they still say I was a traitor?"[63]

22 May: Barricades, first street battles

On the morning of 22 May, bells rang around the city, and Delescluze, as delegate for war of the Commune, issued a proclamation, posted all over Paris:

In the name of this glorious France, mother of all the popular revolutions, permanent home of the ideas of justice and solidarity which should be and will be the laws of the world, march at the enemy, and may your revolutionary energy show him that someone can sell Paris, but no one can give it up, or conquer it! The Commune counts on you, count on the Commune![64]

The Committee of Public Safety issued its own decree:

TO ARMS! That Paris be bristling with barricades, and that, behind these improvised ramparts, it will hurl again its cry of war, its cry of pride, its cry of defiance, but its cry of victory; because Paris, with its barricades, is undefeatable ...That revolutionary Paris, that Paris of great days, does its duty; the Commune and the Committee of Public Safety will do theirs![65]

Despite the appeals, only fifteen to twenty thousand persons, including many women and children, responded. The forces of the Commune were outnumbered five-to-one by the army of Marshal MacMahon.[66]

On the morning of 22 May, the regular army occupied a large area from the Porte Dauphine; to the Champs-de-Mars and the École Militaire, where general Cissey established his headquarters; to the Porte de Vanves. In a short time the 5th corps of the army advanced toward Parc Monceau and Place Clichy, while General Douay occupied the Place de l'Étoile and General Clichant occupied the Gare Saint-Lazaire. Little resistance was encountered in the west of Paris, but the army moved forward slowly and cautiously, in no hurry.

No one had expected the army to enter the city, so only a few large barricades were already in place, on the Rue Saint-Florentin and Rue de l'Opéra, and the Rue de Rivoli. Barricades had not been prepared in advance; some nine hundred barricades were built hurriedly out of paving stones and sacks of earth. Many other people prepared shelters in the cellars. The first serious fighting took place in the afternoon of the 22nd, an artillery duel between regular army batteries on the Quai d'Orsay, and the Madeleine, and National Guard batteries on the terrace of the Tuileries Palace. On the same day, the first executions of National Guard soldiers by the regular army inside Paris took place; some sixteen prisoners captured on the Rue du Bac were given a summary hearing, and then shot.[67]

23 May: Battle for Montmartre; burning of Tuileries Palace

On 23 May the next objective of the army was the butte of Montmartre, where the uprising had begun. The National Guard had built and manned a circle of barricades and makeshift forts around the base of the butte. The garrison of one barricade, at Chaussee Clignancourt, was defended in part by a battalion of about thirty women, including Louise Michelle, the celebrated "Red Virgin of Montmartre", who had already participated in many battles outside the city. She was seized by regular soldiers and thrown into the trench in front of the barricade and left for dead. She escaped and soon afterwards surrendered to the army, to prevent the arrest of her mother. The battalions of the National Guard were no match for the army; by midday on the 23rd the regular soldiers were at the top of Montmartre, and the tricolor flag was raised over the Solferino tower. The soldiers captured 42 guardsmen and several women, took them to the same house on Rue Rosier where generals Clement-Thomas and Lecomte had been executed, and shot them. On the Rue Royale, soldiers seized the formidable barricade around the Madeleine church; 300 prisoners captured with their weapons were shot there, the largest of the mass executions of prisoners.[63]

On the same day, having had little success fighting the army, units of national guardsmen began to take revenge by burning public buildings symbolising the government. The guardsmen led by Paul Brunel, one of the original leaders of the Commune, took cans of oil and set fire to buildings near the Rue Royale and the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Following the example set by Brunel, guardsmen set fire to dozens of other buildings on Rue Saint-Florentin, Rue de Rivoli, Rue de Bac, Rue de Lille, and other streets.

The Tuileries Palace, which had been the residence of most of the monarchs of France from Henry IV to Napoleon III, was defended by a garrison of some three hundred National Guard with thirty cannon placed in the garden. They had been engaged in a day-long artillery duel with the regular army. At about seven in the evening, the commander of the garrison, Jules Bergeret, gave the order to burn the palace. The walls, floors, drapes and woodwork were soaked with oil and turpentine, and barrels of gunpowder were placed at the foot of the grand staircase and in the courtyard, then the fires were set. The fire lasted 48 hours and gutted the palace, except for the southernmost part, the Pavillon de Flore.[68] Bergeret sent a message to the Hotel de Ville: "The last vestiges of royalty have just disappeared. I wish that the same will happen to all the monuments of Paris."[69]

The Richelieu library of the Louvre, connected to the Tuileries, was also set on fire and entirely destroyed. The rest of the Louvre was saved by the efforts of the museum curators and fire brigades.[70] Defenders of the Commune later claimed that many of the fires were caused by artillery from the French army.[71]

Besides public buildings, the National Guard also burned the homes of several people associated with the regime of Napoleon III, such as the home of the playwright Prosper Merimee, the author of Carmen''.[72]

24 May: Burning of Hotel de Ville; executions of Communards, the Archbishop and hostages

At two in the morning on 24 May, Brunel and his men went to the Hotel de Ville, which was still the headquarters of the Commune and of its chief executive, Delescluze. Wounded men were being tended in the halls, and some of the National Guard officers and Commune members were changing from their uniforms into civilian clothes and shaving their beards, preparing to escape from the city. Delescluze ordered everyone to leave the building, and Brunel's men set it on fire.[73]

The battles resumed at daylight on 24 May, under a sky black with smoke from the burning palaces and ministries. There was no co-ordination or central direction on the Commune side; each neighborhood fought on its own. The National Guard disintegrated, with many soldiers changing into civilian clothes and fleeing the city, leaving between 10,000 and 15,000 Communards to defend the barricades. Delescluze moved his headquarters from the Hotel de Ville to the city hall of the 11th arrondissement. More public buildings were set afire, including the Palais de Justice, the Prefecture de Police, the theatres of Chatelet and Porte-Saint-Martin, and the Church of Saint-Eustache.

As the army continued its methodical advance, the summary executions of captured Communard soldiers by the army continued. Informal military courts were established at the École Polytechnique, Chatelet, the Luxembourg Palace, Parc Monceau, and other locations around Paris. The hands of captured prisoners were examined to see if they had fired weapons. The prisoners gave their identity, sentence was pronounced by a court of two or three gendarme officers, the prisoners were taken out and sentences immediately carried out.[74]

Amid the news of the growing number of executions carried out by the army in different parts of the city, the Communards carried out their own executions as a desperate and futile attempt at retaliation. Raoul Rigaut, the chairman of the Committee of Public Safety, without getting the authorization of the Commune, executed one group of four prisoners, before he himself was captured and shot by an army patrol. On 24 May, a delegation of national guardsmen and Gustave Genton, a member of the Committee of Public Safety, came to the new headquarters of the Commune at the city hall of the 11th arrondissment and demanded the immediate execution of the hostages held at the prison of La Roquette. The new prosecutor of the Commune, Théophile Ferré, hesitated and then wrote a note: "Order to the Citizen Director of La Roquette to execute six hostages." Genton asked for volunteers to serve as a firing squad, and went to the La Roquette prison, where many of the hostages were being held. Genton was given a list of hostages and selected six names, including Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris and three priests. The governor of the prison, M. François, refused to give up the Archbishop without a specific order from the Commune. Genton sent a deputy back to the Prosecutor, who wrote "and especially the archbishop" on the bottom of his note. Archbishop Darboy and five other hostages were promptly taken out into the courtyard of the prison, lined up against the wall, and shot.[75]

25 May: Death of Delescluze

By the end of 24 May, the regular army had cleared most of the Latin Quarter barricades, and held three-fifths of Paris. MacMahon had his headquarters at the Quai d'Orsay. The insurgents held only the 11th, 12th, 19th and 20th arrondissements, and parts of the 3rd, 5th, and 13th. Delescluze and the remaining leaders of the Commune, about 20 in all, were at the city hall of the 13th arrondissement on Place Voltaire. A bitter battle took place between about 1,500 national guardsmen from the 13th arrondissement and the Mouffetard district, commanded by Walery Wroblowski, a Polish exile who had participated in the uprising against the Russians, against three brigades commanded by General de Cissey.[76]

During the course of the 25th the insurgents lost the city hall of the 13th arrondissement and moved to a barricade on Place Jeanne-d'Arc, where 700 were taken prisoner. Wroblowski and some of his men escaped to the city hall of the 11th arrondissement, where he met Delescluze, the chief executive of the Commune. Several of the other Commune leaders, including Brunel, were wounded, and Pyat had disappeared. Delescluze offered Wroblowski the command of the Commune forces, which he declined, saying that he preferred to fight as a private soldier. At about seven-thirty Delescluze put on his red sash of office, walked unarmed to the barricade on the Place du Château-d'Eau, climbed to the top and showed himself to the soldiers, and was promptly shot dead.[77]

26 May: Capture of Place de la Bastille; more executions

On the afternoon of 26 May, after six hours of heavy fighting, the regular army captured the Place de la Bastille. The National Guard still held parts of the 3rd arrondissment, from the Carreau du Temple to the Arts-et-Metiers, and the National Guard still had artillery at their strong points at the Buttes-Chaumont and Père-Lachaise, from which they continued to bombard the regular army forces along the Canal Saint-Martin.[78]

As the executions of hundreds of prisoners by the army continued, a contingent of several dozen national guardsmen led by Antoine Clavier, a commissaire and Emile Gois, a colonel of the National Guard, arrived at La Roquette prison and demanded, at gunpoint, the remaining hostages there: ten priests, thirty-five policemen and gendarmes, and two civilians. They took them first to the city hall of the 20th arrondissement; the Commune leader of that district refused to allow his city hall to be used as a place of execution. Clavier and Gois took them instead to Rue Haxo. The procession of hostages was joined by a large and furious crowd of national guardsmen and civilians who insulted, spat upon, and struck the hostages. Arriving at an open yard, they were lined up against a wall and shot in groups of ten. National guardsmen in the crowd opened fire along with the firing squad. The hostages were shot from all directions, then beaten with rifle butts and stabbed with bayonets.[79] According to Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, a defender of the Commune, a total of 63 people were executed by the Commune during the bloody week.[6]

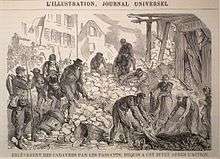

27–28 May: Final battles; massacre at Père-Lachaise Cemetery

On the morning of 27 May, the regular army soldiers of Generals Grenier, Ladmirault and Montaudon launched an attack on the National Guard artillery on the heights of the Buttes-Chaumont. The heights were captured at the end of the afternoon by the first regiment of the French Foreign Legion. The last remaining strongpoint of the National Guard was the cemetery of Père-Lachaise, defended by about 200 men. At 6:00 in the evening, the army used cannon to demolish the gates and the First Regiment of naval infantry stormed into the cemetery. Savage fighting followed around the tombs until nightfall, when the last 150 guardsmen, many of them wounded, were surrounded; and surrendered. The captured guardsmen were taken to the wall of the cemetery, known today as the Communards' Wall, and shot.[80]

On 28 May, the regular army captured the last remaining positions of the Commune, which offered little resistance. In the morning the regular army captured La Roquette prison and freed the remaining 170 hostages. The army took 1,500 prisoners at the National Guard position on Rue Haxo, and 2,000 more at Derroja, near Père-Lachaise. A handful of barricades at Rue Ramponneau and Rue de Tourville held out into the middle of the afternoon, when all resistance ceased.[81]

Communard prisoners and casualities

Prisoners and exiles

Hundreds of prisoners who had been captured with weapons in their hands or gunpowder on their hands had been shot immediately. Others were taken to the main barracks of the army in Paris and after summary trials, were executed there. They were buried in mass graves in parks and squares. Not all prisoners were shot immediately; the French Army officially recorded the capture of 43,522 prisoners during and immediately after Bloody Week. Of these, 1,054 were women, and 615 were under the age of 16. They were marched in groups of 150 or 200, escorted by cavalrymen, to Versailles or the Camp de Satory where they were held in extremely crowded and unsanitary conditions until they could be tried. More than half of the prisoners, 22,727 to be exact, were released before trial for extenuating circumstances or on humanitarian grounds. Since Paris had been officially under a state of siege during the Commune, the prisoners were tried by military tribunals. Trials were held for 15,895 prisoners, of whom 13,500 were found guilty. Ninety-five were sentenced to death; 251 to forced labour; 1,169 to deportation, usually to New Caledonia; 3,147 to simple deportation; 1,257 to reclusion; 1,305 to prison for more than a year; and 2,054 to prison for less than a year.[82]

A separate and more formal trial was held beginning 7 August for the Commune leaders who survived and had been captured, including Théophile Ferré, who had signed the death warrant for the hostages, and the painter Gustave Courbet, who had proposed the destruction of the column in Place Vendôme. They were tried by a panel of seven senior army officers. Ferré was sentenced to death, and Courbet was sentenced to six months in prison, and later ordered to pay the cost of rebuilding the column. He went into exile in Switzerland and died before making a single payment. Five women were also put on trial for participation in the Commune, including the "Red Virgin" Louise Michel. She demanded the death penalty, but was instead deported to New Caledonia.

In October 1871 a commission of the National Assembly reviewed the sentences; 310 of those convicted were pardoned, 286 had their sentences reduced, and 1,295 commuted. Of the 270 condemned to death—175 in their absence—25 were shot, including Ferré and Gustave Genton, who had selected the hostages for execution.[83] Thousands of Communards, including leaders such as Felix Pyat, succeeded in slipping out of Paris before the end of the battle, and went into exile; some 3,500 going to England, 2,000–3,000 to Belgium, and 1,000 to Switzerland.[84] A partial amnesty was granted on 3 March 1879, allowing 400 of the 600 deportees sent to New Caledonia to return, and 2,000 of the 2,400 prisoners sentenced in their absence. A general amnesty was granted on 11 July 1880, allowing the remaining 543 condemned prisoners, and 262 sentenced in their absence, to return to France.[85]

Casualties

Participants and historians have long debated the number of Communards killed during Bloody Week. The official army report by General Félix Antoine Appert mentioned only Army casualties, which amounted, from April through May, to 877 killed, 6,454 wounded, and 183 missing. The report assessed information about Communard casualties only as "very incomplete".[3] The issue of casualties during the Bloody Week arose at a National Assembly hearing on 28 August 1871, when Marshal MacMahon testified. Deputy M. Vacherot told him, "A general has told me that the number killed in combat, on the barricades, or after the combat, was as many as 17,000 men." MacMahon responded, "I don't know what that estimate is based upon; it seems exaggerated to me. All I can say is that the insurgents lost a lot more people than we did." Vacherot continued, "Perhaps this number applies to all of the siege, and to the fighting at Forts d'Issy and Vanves." MacMahon replied, "the number is exaggerated." Vacherot persisted, "It was General Appert who gave me that information. Perhaps he meant both dead and wounded." MacMahon replied, "Ah, well, that's different."[86]

In 1876 Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, who had fought on the barricades during Bloody Week, and had gone into exile in London, wrote a highly popular and sympathetic history of the Commune. At the end, he wrote: "No one knows the exact number of victims of the Bloody Week. The chief of the military justice department claimed seventeen thousand shot." Lissagaray was referring to General Appert, who had reportedly told a National Assembly deputy that there had been 17,000 Commune casualties. "The municipal council of Paris," Lissagaray continued, "paid for the burial of seventeen thousand bodies; but a large number of persons were killed or cremated outside of Paris." "It is no exaggeration," Lissagaray concluded, "to say twenty thousand, a number admitted by the officers."[6] In a new 1896 edition Lissagaray emphasized, "Twenty thousand men, women and children killed after the fighting in Paris and in the provinces."[87] Several historians have accepted the 20,000 figure, among them Pierre Milza,[88] Alfred Cobban[89] and Benedict Anderson.[90] Vladimir Lenin seized upon Lissagaray's estimate as emblematic of ruling-class brutality: "20,000 killed in the streets...Lessons: bourgeoisie will stop at nothing."[91]

Between 1878 and 1880, a French historian and member of the Académie française, Maxime Du Camp, wrote Les Convulsions de Paris. Du Camp had witnessed the last days of the Commune, went inside the Tuileries Palace shortly after the fires were put out, witnessed the executions of Communards by soldiers, and the bodies in the streets. He studied the question of the number of dead, and studied the records of the office of inspection of the Paris cemeteries, which was in charge of burying the dead. Based on their records, he reported that between 20 and 30 May, 5,339 corpses of Communards had been taken from the streets or Paris morgue to the city cemeteries for burial. Between 24 May and 6 September, the office of inspection of cemeteries reported that an additional 1,328 corpses were exhumed from temporary graves at 48 sites, including 754 corpses inside the old quarries near Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, for a total of 6,667.[92] Modern Marxist critics attacked du Camp and his book; Collette Wilson called it "a key text in the construction and promulgation of the reactionary memory of the Commune" and Paul Lidsky called it "the bible of the anti-Communard literature."[93] In 2012, however, historian Robert Tombs made a new study of the Paris cemetery records and placed the number killed between 6,000 and 7,000, confirming du Camp's research.[4] Jacques Rougerie, who had earlier accepted the 20,000 figure, wrote in 2014, "the number ten thousand victims seems today the most plausible; it remains an enormous number for the time."[5]

Critique

Contemporary artists and writers

French writers and artists had strong views about the Commune. Gustave Courbet was the most prominent artist to take part in the Commune, and was an enthusiastic participant and supporter, though he criticized its executions of suspected enemies. On the other side, the young Anatole France described the Commune as "A committee of assassins, a band of hooligans [fripouillards], a government of crime and madness."[94] The diarist Edmond de Goncourt, wrote, three days after La Semaine Sanglante, "...the bleeding has been done thoroughly, and a bleeding like that, by killing the rebellious part of a population, postpones the next revolution... The old society has twenty years of peace before it..."[95]