Parietal lobe

| Parietal lobe | |

|---|---|

|

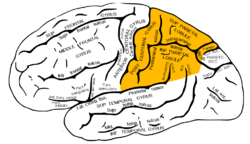

Principal fissures and lobes of the cerebrum viewed laterally. (Parietal lobe is shown in yellow) | |

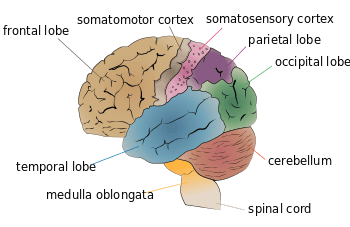

Lateral surface of left cerebral hemisphere, viewed from the side. (Parietal lobe is shown in orange.) | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Cerebrum |

| Components | The cerebral cortex |

| Artery |

Anterior cerebral Middle cerebral |

| Vein | Superior sagittal sinus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | lobus parietalis |

| MeSH | A08.186.211.730.885.213.670 |

| NeuroNames | hier-77 |

| NeuroLex ID | Parietal lobe |

| TA | A14.1.09.123 |

| FMA | 61826 |

The parietal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The parietal lobe is positioned above the occipital lobe and behind the frontal lobe and central sulcus.

The parietal lobe integrates sensory information among various modalities, including spatial sense and navigation (proprioception), the main sensory receptive area for the sense of touch (mechanoreception) in the somatosensory cortex which is just posterior to the central sulcus in the postcentral gyrus,[1] and the dorsal stream of the visual system. The major sensory inputs from the skin (touch, temperature, and pain receptors), relay through the thalamus to the parietal lobe.

Several areas of the parietal lobe are important in language processing. The somatosensory cortex can be illustrated as a distorted figure — the homunculus (Latin: "little man"), in which the body parts are rendered according to how much of the somatosensory cortex is devoted to them.[2] The superior parietal lobule and inferior parietal lobule are the primary areas of body or spatial awareness. A lesion commonly in the right superior or inferior parietal lobule leads to hemineglect.

The name comes from the overlying parietal bone, which is named from the Latin paries-, meaning "wall".

Structure

The parietal lobe is defined by three anatomical boundaries: The central sulcus separates the parietal lobe from the frontal lobe; the parieto-occipital sulcus separates the parietal and occipital lobes; the lateral sulcus (sylvian fissure) is the most lateral boundary, separating it from the temporal lobe; and the medial longitudinal fissure divides the two hemispheres. Within each hemisphere, the somatosensory cortex represents the skin area on the contralateral surface of the body.[2]

Immediately posterior to the central sulcus, and the most anterior part of the parietal lobe, is the postcentral gyrus (Brodmann area 3), the primary somatosensory cortical area. Dividing this and the posterior parietal cortex is the postcentral sulcus.

The posterior parietal cortex can be subdivided into the superior parietal lobule (Brodmann areas 5 + 7) and the inferior parietal lobule (39 + 40), separated by the intraparietal sulcus (IPS). The intraparietal sulcus and adjacent gyri are essential in guidance of limb and eye movement, and—based on cytoarchitectural and functional differences—is further divided into medial (MIP), lateral (LIP), ventral (VIP), and anterior (AIP) areas.

Function

Cortical functions of the parietal lobe are:

through touch alone without other sensory input (i.e., visual)

- Graphesthesia - recognizing writing on skin by touch alone

- Touch localization (bilateral simultaneous stimulation)

The parietal lobe plays important roles in integrating sensory information from various parts of the body, knowledge of numbers and their relations,[3] and in the manipulation of objects. Its function also includes processing information relating to the sense of touch.[4] Portions of the parietal lobe are involved with visuospatial processing. Although multisensory in nature, the posterior parietal cortex is often referred to by vision scientists as the dorsal stream of vision (as opposed to the ventral stream in the temporal lobe). This dorsal stream has been called both the "where" stream (as in spatial vision)[5] and the "how" stream (as in vision for action).[6] The posterior parietal cortex (PPC) receives somatosensory and/or visual input, which then, through motor signals, controls movement of the arm, hand, as well as eye movements.[7]

Various studies in the 1990s found that different regions of the posterior parietal cortex in macaques represent different parts of space.

- The lateral intraparietal (LIP) contains a map of neurons (retinotopically-coded when the eyes are fixed[8]) representing the saliency of spatial locations, and attention to these spatial locations. It can be used by the oculomotor system for targeting eye movements, when appropriate.[9]

- The ventral intraparietal (VIP) area receives input from a number of senses (visual, somatosensory, auditory, and vestibular[10]). Neurons with tactile receptive fields represent space in a head-centered reference frame.[10] The cells with visual receptive fields also fire with head-centered reference frames[11] but possibly also with eye-centered coordinates[10]

- The medial intraparietal (MIP) area neurons encode the location of a reach target in nose-centered coordinates.[12]

- The anterior intraparietal (AIP) area contains neurons responsive to shape, size, and orientation of objects to be grasped[13] as well as for manipulation of hands themselves, both to viewed[13] and remembered stimuli.[14] The AIP has neurons that are responsible for grasping and manipulating objects through motor and visual inputs. The AIP and ventral premotor working together, are responsible for visuomotor transformations for actions of the hand.[7]

More recent fMRI studies have shown that humans have similar functional regions in and around the intraparietal sulcus and parietal-occipital junction.[15] The human "parietal eye fields" and "parietal reach region", equivalent to LIP and MIP in the monkey, also appear to be organized in gaze-centered coordinates so that their goal-related activity is "remapped" when the eyes move.[16] Both the left and right parietal systems play a determining role in self transcendence, the personality trait measuring predisposition to spirituality.[17]

Clinical significance

Features of parietal lobe lesions are as follows:

- Unilateral parietal lobe

- Contralateral hemisensory loss

- Astereognosis – inability to determine 3-D shape by touch.

- Agraphaesthesia – inability to read numbers or letters drawn on hand, with eyes shut.

- Contralateral homonymous Lower quadrantanopia

- Asymmetry of optokinetic Nystagmus (OKN)

- Sensory Seizures

- Extinction phenomenon (contralateral)

- Dominant hemisphere

- Dysphasia/Aphasia

- Dyscalculia

- Dyslexia –a general term for disorders that can involve difficulty in learning to read or interpret words, letters, and other symbols.

- Apraxia – inability to perform complex movements in the presence of normal motor, sensory and cerebellar function.

- Agnosia (tactile agnosia) – inability to recognize or discriminate.

- Gerstmann syndrome – Characterized by acalculia, agraphia, finger anomia and difficulty in differentiation of right and left.

- Non dominant hemisphere

- Spatial disorientation

- Constructional apraxia

- Dressing apraxia

- Anosognosia – a condition in which a person suffering disability seems to be unaware of the existence of his or her disability.

Damage to the right hemisphere of this lobe results in the loss of imagery, visualization of spatial relationships and neglect of left-side space and left side of the body. Even drawings may be neglected on the left side. Damage to the left hemisphere of this lobe will result in problems in mathematics, long reading, writing, and understanding symbols. The parietal association cortex enables individuals to read, write, and solve mathematical problems.The sensory inputs from the right side of the body go to the left side of the brain and vice versa.

The syndrome of hemispatial neglect is usually associated with large deficits of attention of the non-dominant hemisphere. Optic ataxia is associated with difficulties reaching toward objects in the visual field opposite to the side of the parietal damage. Some aspects of optic ataxia have been explained in terms of the functional organization described above.

Apraxia is a disorder of motor control which can be referred neither to “elemental” motor deficits nor to general cognitive impairment. The concept of apraxia was shaped by Hugo Liepmann about a hundred years ago.[18][19] Apraxia is predominantly a symptom of left brain damage, but some symptoms of apraxia can also occur after right brain damage.[20]

Amorphosynthesis is a loss of perception on one side of the body caused by a lesion in the parietal lobe. Usually, left-sided lesions cause agnosia, a full-body loss of perception, while right-sided lesions cause lack of recognition of the person’s left side and extrapersonal space. The term amorphosynthesis was coined by D. Denny-Brown to describe patients he studied in the 1950s.[21]

Can also result in sensory impairment where one of the affected person's senses (sight, hearing, smell, touch, taste and spatial awareness) is no longer normal. [22] .[23]

Additional images

-

Lobes

-

Drawing to illustrate the relations of the brain to the skull.

-

Ventricles of brain and basal ganglia.Superior view. Horizontal section.Deep dissection

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~lngbrain/cglidden/parietal.html

- 1 2 Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. L. & Wegner, D. M. (2009). Psychology. (2nd ed.). New Work (NY): Worth Publishers.

- ↑ Blakemore & Frith (2005). The Learning Brain. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-2401-6

- ↑ Penfield, W., & Rasmussen, T. (1950). The cerebral cortex of a man: A clinical study of localization of function. New York: Macmillan.

- ↑ Mishkin M, Ungerleider LG. (1982) Contribution of striate inputs to the visuospatial functions of parieto-preoccipital cortex in monkeys. Behav Brain Res. 1982 Sep;6(1):57-77.

- ↑ Goodale MA, Milner AD. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends Neurosci. 1992 Jan;15(1):20-5.

- 1 2 Fogassi L, Luppino G. (2005).Motor functions of the parietal lobe. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 15:626-631.

- ↑ Kusunoki M, Goldberg ME (March 2003). "The time course of perisaccadic receptive field shifts in the lateral intraparietal area of the monkey". J. Neurophysiol. 89 (3): 1519–27. doi:10.1152/jn.00519.2002. PMID 12612015.

- ↑ Goldberg ME, Bisley JW, Powell KD, Gottlieb J (2006). "Saccades, salience and attention: the role of the lateral intraparietal area in visual behavior". Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. 155: 157–75. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)55010-1. ISBN 9780444519276. PMC 3615538

. PMID 17027387.

. PMID 17027387. - 1 2 3 Avillac M, Deneve S, Olivier E, Pouget A, Duhamel JR (2005). "Reference frames for representing visual and tactile locations in parietal cortex". Nat Neurosci. 8 (7): 941–9. doi:10.1038/nn1480. PMID 15951810.

- ↑ Zhang T, Heuer HW, Britten KH (2004). "Parietal area VIP neuronal responses to heading stimuli are encoded in head-centered coordinates". Neuron. 42 (6): 993–1001. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.008. PMID 15207243.

- ↑ Pesaran B, Nelson MJ, Andersen RA (2006). "Dorsal premotor neurons encode the relative position of the foot, eye, and goal during reach planning". Neuron. 51 (1): 125–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.025. PMC 3066049

. PMID 16815337.

. PMID 16815337. - 1 2 Murata A, Gallese V, Luppino G, Kaseda M, Sakata H (May 2000). "Selectivity for the shape, size, and orientation of objects for grasping in neurons of monkey parietal area AIP". J. Neurophysiol. 83 (5): 2580–601. PMID 10805659.

- ↑ Murata A, Gallese V, Kaseda M, Sakata H (May 1996). "Parietal neurons related to memory-guided hand manipulation". J. Neurophysiol. 75 (5): 2180–6. PMID 8734616.

- ↑ Culham JC, Valyear KF (2006). "Human parietal cortex in action". Curr Opin Neurobiol. 16 (2): 205–12. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.005. PMID 16563735.

- ↑ Medendorp WP, Goltz HC, Vilis T, Crawford JD. (2003) Gaze-centered updating of visual space in human parietal cortex. J Neurosci. 16;23(15):6209-14.

- ↑ Urgesi, Cosimo; S M Aglioti; M Skrap; F Fabbro (2010-02-11). "The Spiritual Brain: Selective Cortical Lesions Modulate Human Self-Transcendence". Neuron. 65 (3): 309–319. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.026. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ↑ Goldenberg, George (2009). "Apraxia and the Parietal Lobes". Neuropsychologia. 47 (6): 1449–1459. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.014. PMID 18692079.

- ↑ Liepmann, 1900

- ↑ Khan AZ, Pisella L, Vighetto A, Cotton F, Luauté J, Boisson D, Salemme R, Crawford JD, Rossetti Y, et al. (2011). "Optic ataxia errors depend on remapped, not viewed, target location". Nat Neurosci. 8 (4): 418–20. doi:10.1038/nn1425. PMID 15768034.

- ↑ Denny-Brown, D., and Betty Q. Banker. "Amorphosynthesis from Left Parietal Lesion." A.M.A. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 71, no. 3 (March 1954): 302-13.

- ↑ http://alzheimers.about.com/library/blparietal.htm

- ↑ Murat Yildiz et al. "Parietal Lobes in Schizophrenia: Do They Matter?", Schizophrenia Research and Treatment Volume 2011 (2011)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parietal lobe. |