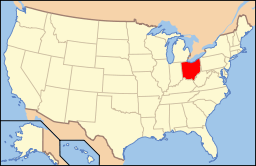

Paleontology in Ohio

Paleontology in Ohio refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Ohio. Ohio is well known for having a great quantity and diversity of fossils preserved in its rocks. The state's fossil record begins early in the Paleozoic era, during the Cambrian period. Ohio was generally covered by seawater from that time on through the rest of the early Paleozoic. Local invertebrates included brachiopods, cephalopods, coral, graptolites, and trilobites. Vertebrates included bony fishes and sharks. The first land plants in the state grew during the Devonian. During the Carboniferous, Ohio became a more terrestrial environment with an increased diversity of plants that formed expansive swampy deltas. Amphibians and reptiles began to inhabit the state at this time, and remained present into the ensuing Permian. A gap in the local rock record spans from this point until the start of the Pleistocene. During the Ice Age, Ohio was home to giant beavers, humans, mammoths, and mastodons. Paleo-Indians collected fossils that were later incorporated into their mounds. Ohio has been the birthplace of many world famous paleontologists, like Charles Schuchert. Many significant fossils curated by museums in Europe and the United States were found in Ohio.[1] Major local fossil discoveries include the 1965 discovery of more than 50,000 Devonian fish fossils in Cuyahoga County. The Ordovician trilobite Isotelus maximus is the Ohio state fossil.

Prehistory

No Precambrian fossils are known from Ohio, so the state's fossils record does not start until the Cambrian Period.[2] During the later part of the period, Ohio was covered in seawater and located 10 degrees south of the equator. By the end of the Cambrian the sea was shallow and the climate dry. Although marine life was diverse during the Cambrian little is known about Ohio's Cambrian inhabitants because the only specimens known were found in core samples.[2]

During the Ordovician Ohio was covered in a warm shallow sea that was deepest in the eastern half of the state. The environment was reminiscent of the modern Bahamas. Ohio was twenty degrees south of the equator at the time. Islands sometimes rose above sea level in western Ohio. Later on during the Ordovician the sea got deeper and spread across the state's entirety, but the seas gradually withdrew. Bryozoans are common Ohio fossils of Ordovician age. Others include brachiopods, cephalopods, trilobites, horn corals, snails, clams, echinoderms, and graptolites.[2]

Ohio was dry land during the early Silurian. Later warm shallow seas returned to Ohio. Ohio was 20 degrees south of the equator. The seas got deeper in the middle Silurian.[2] The northern and eastern areas of the state were inundated by deeper waters than the rest of the state. Between the two depths a reef system composed of corals and sponges formed. The state was also home to brachiopods and echinoderms,[3] During the late Silurian the seas got shallower again. Other fossils included echinoderms, clams, brachiopods, and cephalopods.[2]

During the early Devonian only eastern Ohio was still covered by the sea. Ohio was located near the equator. Brachiopods and echinoderms still remained in the area during the Early Devonian.[3] By the middle Devonian the seas had expanded across the state once more. Sharks and bony fishes appeared in the Middle Devonian. True land plants also appeared around this time. As the Devonian passed on the sea's circulation weakened and its oxygen levels dropped, leading to a state described as the "'stinking seas'".[4] Few organisms lived in these low oxygen conditions.[3] Nevertheless, overall Devonian Ohio had a rich fauna including coral reefs, bryozoans, brachiopods, trilobites, cephalopods, clams, crinoids, ostracodes.[4]

The rock record of the early Mississippian in Ohio demonstrates the presence of deltas and bodies of flowing water. During the late Mississippian Ohio was covered by a shallow sea. Near the end of the Mississippian the seas withdrew from the state. Ohio was located near the equator. The fossil record of Ohio includes greater numbers of land plants, brachiopods, clams, crinoids, fishes.[4]

Ohio was a low-lying swampy plain near the coast during the Pennsylvanian. Its latitude was near the equator. Sea levels rose and fell sporadically so the rock record shows a history of land, freshwater, and sea deposits. Fossils of land plants are common in Ohio's Pennsylvanian rocks. Amphibians, reptiles, and freshwater clam fossils are also known from the time. The marine life of Ohio included crinoids, snails, cephalopods, brachiopods, and fishes. Trilobites were also present, but their fossils are rare.[4]

By the Permian period the sea had left completely. Local bodies of water were then lakes and rivers rather than saltwater.[3] Southeastern Ohio was a swamp-covered coastal plain.[4] Ferns and horsetails were among the state's rich flora.[3] Ohio was only about 5 degrees north of the equator. Sand and mud deposited on local river deltas gradually filled in the swamp. Later in the Permian Ohio was subjected to geologic uplift and its sediments were eroded away. Permian fossils aren't especially common in Ohio, but include snails, clams, fishes, plants, amphibians, and reptiles. Marine fossils from this period are rare.[4]

From about 248 to 1.6 million years ago Ohio was above sea level, so its rocks were eroded away rather than deposited. Dinosaurs probably lived in Ohio but there is no fossil record of their presence.[4] The ensuing Tertiary period of the Cenozoic era is also missing from the local rock record.[3] However, during the Quaternary period Ohio was worked over by glacial activity. A mile thick glacier was position over the area now occupied by Cleveland during the early part of this period.[3] About two thirds of Ohio was covered by such glaciers. Entire Pleistocene forests buried by the action of glaciers have been discovered in Ohio.[5] Around this time Ohio was inhabited by giant beavers, mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths and more modern animals, including humans.[4]

History

Indigenous interpretations

Fossil tusks collected by native people more than 2,000 years ago have been discovered interred in the state's mounds.[6] In 1748, a French military officer named Fabri wrote a letter to Georges Cuvier, mentioning that the local natives attribute the region's fossil bones to a creature called the grandfather of the buffalo.[7]

Scientific research

One of the most significant early fossil finds in Ohio was made between 1837 and 1838. John Locke collected the tail of a new species of trilobite that he named Isotelus maximus while mapping the geology of southwestern Ohio.[8] A related discovery occurred in 1919. While excavating an outlet tunnel for the Mad River's Huffman Dam, workers discovered a giant specimen of Isotelus. The specimen was 14 1/2 inches long and 10 1/4 inches wide.[9]

In Spring, 1965 a major discovery of Devonian fossils occurred in Cuyahoga County. A collaboration between the state Highway Department, Ohio Bureau of Public Roads and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History led by the Smithsonian's David Dunkle uncovered as many as 50,000 fish fossils from a construction site. By the ensuing November 120 or more different species had been found there, with half previously unknown to science.[10]

Later, two elementary school teachers and their students catalyzed the process of getting Isotelus recognized as Ohio's state fossil. Doris Swabb of Beavertown School in Kettering took her third grade students to the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery (then Dayton Museum of Natural History). Virginia Evers likewise took her fourth grade class from St. Anthony School to the museum. After seeing a cast of the Huffman Dam Isotelus, they got the idea to get the specimen recognized as Ohio's official state fossil. The students sent letters to Robert L. Corbin and Robert E. Hickey, members of the Ohio House of Representatives. Both Representatives agreed to sponsor legislation making the designation official. Senator Charles F. Horn agreed to introduce legislation for the same purpose in the Ohio senate.[11]

Newspapers and television gave extensive coverage to the proposal for making Isotelus the Ohio state fossils. Many local geological groups came forward in support of the idea. The Ohio Division of Geological Survey provided technical assistance for the drafting of the bill itself, which designated Isotelus generally for the state fossils rather than the individual specimen discovered during the Huffman Dam excavations. Very little opposition to the bill was raised in either legislative body.[11] On June 20, 1985 Ohio House Bill 145 declared the trilobite genus Isotelus to be Ohio's state invertebrate fossil.[12]

Protected areas

- Trammel Fossil Park

People

- Erwin Hinckly Barbour was born near Oxford in 1856.

- William Berryman Scott was born in Cincinnati on February 12, 1858.

- Charles Schuchert was born in Cincinnati on 3 July, 1858.

- Walter Hermann Bucher was born in Akron on March 12, 1888.

- Erich Maren Schlaikjer was born in Newtown on November 22, 1905.

- Stanley John Olsen was born in Akron on 24 June, 1919

Natural history museums

- Cincinnati Museum of Natural History & Science, Cincinnati

- Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland

- Karl Limper Geology Museum, Oxford

Notable clubs and associations

See also

- Paleontology in Indiana

- Paleontology in Kentucky

- Paleontology in Michigan

- Paleontology in Pennsylvania

- Paleontology in West Virginia

Footnotes

- ↑ Shrake (2003); "Fossil Collecting in Ohio", page 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ohio Division of Geological Survey (2001); "A Brief Summary of the Geologic History of Ohio", page 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ausich, Scotchmoor, and Springer (2006); "Paleontology and geology".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ohio Division of Geological Survey (2001); "A Brief Summary of the Geologic History of Ohio", page 1.

- ↑ Shrake (2003); "Where Fossils are Found in Ohio", page 2.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Ivory and Monsters", page 9.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Georges Cuvier's Archives of Indian Paleontology", page 62.

- ↑ Shrake (2005); "Isotelus and its History in Ohio", page 1.

- ↑ Shrake (2005); "Isotelus and its History in Ohio", page 2.

- ↑ Murray (1974); "Ohio", pages 233-234.

- 1 2 Shrake (2005); "How Isotelus was Chosen as the State Fossil of Ohio", page 1.

- ↑ Shrake (2005); "Isotelus: Ohio's State Fossil", page 1.

- 1 2 Garcia and Miller (1998); "Appendix C: Major Fossil Clubs", page 198.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Ohio. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleontology in the United States#Ohio |

- "A Brief Summary of the Geologic History of Ohio". GeoFacts. Number 23. Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey. July 2001.

- Ausich, William, Judy Scotchmoor, Dale Springer. July 21, 2006. "Ohio, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed October 1, 2012.

- Garcia; Frank A. Garcia; Donald S. Miller (1998). Discovering Fossils. Stackpole Books. p. 212. ISBN 0811728005.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian. 1974. Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. 348 pp.

- Shrake, Douglas L. "Fossil Collecting in Ohio". GeoFacts. Number 17. Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey. March 2003.

- Shrake, Douglas L. "Isotelus: Ohio's State Fossil". GeoFacts. Number 6. Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey. May 2005.