Orania, Northern Cape

| Orania | |

|---|---|

|

A view of the town of Orania | |

Orania  Orania  Orania

| |

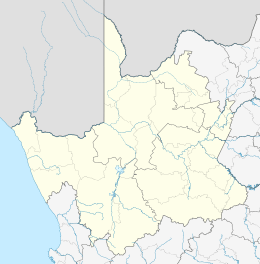

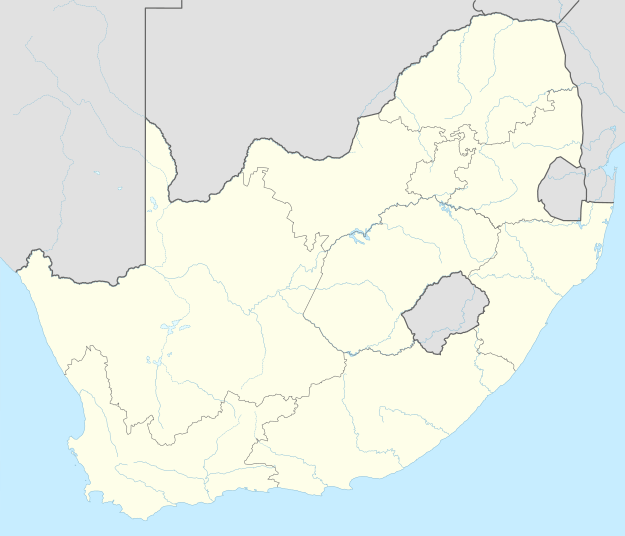

| Coordinates: 29°49′S 24°24′E / 29.817°S 24.400°ECoordinates: 29°49′S 24°24′E / 29.817°S 24.400°E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Northern Cape |

| District | Pixley ka Seme |

| Municipality | Thembelihle |

| Established | 1963 |

| Named for | Orange River |

| Government | |

| • Type | Representative council |

| • Chairman of the Orania Representative Council (Mayor) | Carel Boshoff iv |

| • Chairman of Vluytjeskraal Share Block (VAB) | Chris Jacobs |

| • President of the Orania Movement | Carel Boshoff iv |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 8.95 km2 (3.46 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,180 m (3,870 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1][2] | |

| • Total | 892 |

| • Estimate (2014) | 1,085 |

| • Density | 100/km2 (260/sq mi) |

| Racial makeup (2011)[1] | |

| • Black African | 0.9% |

| • Coloured | 1.9% |

| • White | 97.2% |

| First languages (2011)[1] | |

| • Afrikaans | 98.4% |

| • English | 1.6% |

| Postal code (street) | 8752 |

| PO box | 8752 |

| Area code | 053 |

| Website | http://www.orania.co.za/ |

Orania is an Afrikaner-only South African town located along the Orange River in the arid Karoo region of Northern Cape province.[3] The town is split in two halves by the R369 road, and lies halfway between Cape Town and Pretoria.[4]

The aim of the town is to create a stronghold for Afrikaans and the Afrikaner identity by keeping their language and culture alive. Anyone who defines themselves as an Afrikaner and identifies with Afrikaner ethnicity is welcome in Orania.[5]

Critics accuse the town authorities of rejecting the Rainbow Nation concept,[6] and trying to recreate pre-democratic South Africa within an enclave,[7] while residents contend that they are motivated by the desire to preserve their linguistic and cultural heritage and protect themselves from high crime levels,[8][9] and that they are seeking the right to self-determination as provided by the Constitution of South Africa.[3] The town's relations with the South African government are non-confrontational, and although opposed to aspirations of the community,[10] the government has recognised them as legitimate.[11]

The small community has a radio station and its own currency, the Ora.[12] The population was 1,085 at the time of a local census in 2014,[2] and was reportedly growing steadily at the time.[8] News24 reported on 7 June 2016 that there were by that time 1,300 Afrikaners in Orania.[13] More than 100 businesses are located in Orania as of 2013.[14] Due to its unusual nature, the town is often visited by journalists and documentary-makers.[12]

Purpose

According to its founders, the purpose of Orania is to create a town where the preservation of Afrikanerdom's cultural heritage is strictly observed and Afrikaner selfwerksaamheid ("self reliance") is an actual practice, not just an idea. All jobs, from management to manual labour, are filled by Afrikaners only; non-Afrikaner workers are not permitted unless they have skills no resident has. "We do not want to be governed by people who are not Afrikaners", said Potgieter, the previous chairman. "Our culture is being oppressed and our children are being brainwashed to speak English".[15]

The town's ultimate objective is to create an Afrikaner majority in the northwestern Cape, by encouraging the construction of other such towns, with the eventual goal of an Afrikaner majority in the area and an independent Afrikaner state between Orania and the west coast, also known as a volkstaat.[16]

Carel Boshoff, the founding father of Orania, had originally envisaged a population of 60,000 after 15 years.[17] While he conceded that most Afrikaners might decide not to move to the volkstaat, he thought that it is nevertheless essential Afrikaners have this option, since this will make them feel more secure, thereby reducing tensions in the rest of South Africa. In this regard he considered it as being analogous with Israel, which serves as a refuge for Jews from all over the world.[18]

Newcomers often say their decision to move to Orania was motivated by a desire to escape the violent crime prevalent in the rest of the country,[19] and many had been previously victims of crimes,[3] while Orania residents claim the town is a secure environment and they have no need to lock their house doors.[20]

Ideological origins

The idea that white South Africans should concentrate in a limited region of South Africa was first circulated by the South African Bureau of Racial Affairs (SABRA) in 1966.[22] By the 1970s, the SABRA advocated the idea of transforming South Africa into a commonwealth, where population groups would develop parallel to each other.[22] May 1984 saw the establishment of the Afrikaner Volkswag, an organisation founded by Carel Boshoff, a right-wing academic, to put the ideas of the SABRA into practice.[22] Boshoff regarded contemporary plans of the white-minority government to retain control through limited reforms as doomed to fail.[23] Believing that black-majority rule could not be avoided, he instead supported the creation of a separate, smaller state for the Afrikaner nation.[23]

In 1988 Boshoff founded the Afrikaner-Vryheidstigting (Afrikaner Freedom Foundation) or Avstig.[22] At the time, mainstream right-wingers supported the bantustan policy, which allocated 13% of South Africa’s land area for black South Africans, while leaving the remaining 87% to whites.[24] The founding principles of the Avstig were based on the belief that since black majority rule was unavoidable and white minority rule morally unjustifiable, Afrikaners would have to form their own nation, or volkstaat, in a smaller part of South Africa.[18] Orania was intended to be the basis of the volkstaat, which would come into existence once a large number of Afrikaners moved to Orania and other such ‘growth points’,[18] and would eventually include the towns of Prieska, Britstown, Carnarvon, Williston and Calvinia, reaching the west coast.[25]

Boshoff's plans excluded the area of traditional Boer republics in the Transvaal and the Free State, which encompass the economic heartland of South Africa and much of its natural resources, instead focussing on an economically underdeveloped and semi-desert area in the north-western Cape.[18] This desert state, Orandeë, because of its very inhospitableness would not be feared or coveted by the South African government.[26] Even proponents of the idea conceded that this model would demand significant economic sacrifices from Afrikaners who moved to the volkstaat.[18] The model is based on the principle of ‘own labour’, requiring that all work in the volkstaat be performed by its citizens, including the ploughing fields, collection of garbage and tending of gardens, which is traditionally performed by blacks in the rest of South Africa.[27]

History

The Orania region has been inhabited since about 30,000 years ago by Stone Age hunter-gatherers who lived a nomadic lifestyle.[28] A number of late Stone Age engravings indicate the presence of San people, who remained the main cultural group until the second half of the 1700s, with the arrival of white hunters, trekkers and Griqua people.[28] The earliest indication of the presence of white people in the area of Orania dates to 1762, and in the early 19th century many farmers moved seasonally back and forth across the Orange River in search of better grazing.[28] An 1842 Rawstone map shows the farm Vluytjeskraal,[28] on which Orania would later be built.[22] The first known inhabitant of what is today Orania was Stephanus Ockert Vermeulen, who purchased the farm Vluytjeskraal in 1882.[29]

Orania was established in 1963 by the Department of Water Affairs, to house the workers who were building the Vanderkloof Dam.[30] Initially known as Vluytjeskraal, the town acquired its current name, a variation of the Afrikaans word oranje, referring to the adjoining river,[31] after it was chosen in a competition.[32] By 1965 it was home to 56 families.[32] Coloured workers who participated in the construction project lived in a separate area named Grootgewaagd.[33] The first phase of the project was completed in 1976.[33] After the dam was completed most of the workers moved away, and the town fell into disrepair.[30] The department completely abandoned Orania in 1981,[34] though a group of coloured people continued to live in Grootgewaagd.[33]

In December 1990, about 40 Afrikaner families, headed by Carel Boshoff, the son-in-law of former South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, bought the dilapidated town for around US$ 200,000,[35] on behalf of the Orania Bestuursdienste (OBD).[36] The first 13 inhabitants moved in April 1991.[37] During the same month, the people who still lived in Grootgewaagd were evicted, and the village was renamed Kleingeluk.[38] At that time, the town consisted of 90 houses in Orania and 60 in Kleingeluk, all in a grave state of disrepair.[38] In August 1991 the 2,300 hectares (5,700 acres) farm Vluytjeskraal 272 was added to Orania.[39] The town council was established in February 1992.[40] Orania elected its own transitional representative council, a temporary form of local government created after the end of apartheid, in 1995.[41] Construction on an irrigation scheme to cover a 400 hectares (990 acres) area began in 1995 and was completed in October 1996.[42]

In a conciliatory gesture, then-President Nelson Mandela visited the town in 1995 to have tea with Betsie Verwoerd, widow of Hendrik Verwoerd.[43] Orania reached 200 permanent inhabitants in 1996,[37] while the 2001 Census found 519 residents.[44] By 1998 R15 million had been invested in the town, for expenses including the upgrading of water and electricity supply, roads and businesses.[45] A violent incident occurred just outside Orania in April 2000, when a white man shot and wounded a 17-year-old black girl, hitting her leg.[46]

In December 2000, the provincial government ordered the dissolution of Orania's town council and its absorption into a new municipality along with neighbouring towns.[47][48] Oranians lodged an application with the Northern Cape High Court, which found that negotiations between the residents of Orania and the government for a compromise on Orania's municipal status should take place;[49] until such an agreement can be reached, Orania will retain its status quo.[50] By 2003 local amenities included a holiday resort on the Orange River, a home for senior citizens, two schools, a private hospital and a growing agricultural sector.[18]

A dispute arose in May 2005 with a faction of residents who claimed the town was being run like a 'mafia', with a number of lawsuits being filed as part of the dispute.[51] A raid on the town's radio station in November 2005 was linked to a tip-off received from internal dissenters.[52] The dissenters ultimately left the community.[53] In November 2005, around 60 Coloured families who lived in Kleingeluk before 1991 lodged a land claim with the government for around 483 hectares (1,190 acres) of land within Orania.[54] The land claim was settled in December 2006 when the South African government agreed to pay the claimants R2.9 million in compensation.[55]

A R5 million shopping centre, the Saamstaan-winkelsentrum, was inaugurated in 2006.[56] In 2011 the farm Vluytjeskraal-Noord was bought by residents of Orania, though it was set up as a separate legal entity and intended for residential development rather than agriculture.[57] Commercial developments launched in 2013 include Stokkiesdraai Avontuurpark, an adventure park, and Ou Karooplaas Winkelsentrum, a shopping centre.[58]

Geography and climate

The area around the town is semi-arid.[59] Orania is part of the Nama Karoo biome, and receives 200-250mm of rain a year.[60] More than 30,000 trees have been planted in Orania and the surrounding farmlands.[16] Prospective residents are warned of the inclement weather conditions, with extreme temperature differences between summer and winter.[61]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average high °C (°F) | 34.3 (93.7) |

34.1 (93.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.9 (66) |

23 (73) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.2 (81) |

30.1 (86.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

27.06 (80.69) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.5 (34.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.58 (51.03) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 65 (2.56) |

5 (0.2) |

30 (1.18) |

26 (1.02) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

129 (5.08) |

255 (10.04) |

| Source: [60] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

.png)

A local census carried out in 2014 found 1,085 inhabitants distributed in 386 households, for an average of 3.5 people per household,[2] with children making up a quarter of the population in 2007.[62] According to town authorities, the population had grown by 10% annually over the three years to 2015.[63] Male residents outnumbered females 60% to 40% in 2011,[1] and the lack of young women is a cause of complaints among local men.[64]

White South Africans were the main population group at the time of the 2011 census, representing 97.2% of the total.[1] Afrikaans is the only language used in all spheres of local life.[65] According to a 2014 census carried out by town authorities, Afrikaans is the main language spoken at home for 95% of residents, followed by English with 2%, with speakers of both English and Afrikaans making up the remaining 3%.[2]

Religion

Orania is a deeply religious community, with local churches including the Dutch Reformed Church, Apostoliese Geloofsending, Afrikaanse Protestantse Kerk, Evangelies-Gereformeerde Kerk, Gereformeerde Kerk, Hervormde Kerk, Israel Visie and Maranata Kerk;[66] all are Protestant, with the exception of Maranata which is part of the Charismatic Movement.[67] The origin of Orania residents from various parts of South Africa means that newcomers brought a relatively large variety of denominations to their new town.[67] On important holidays such as the Day of the Vow interdenominational services are held.[67] Works stops on Sundays.[20] According to a 2014 local census, the Afrikaans Protestant Church was the most popular denomination, followed by 21.9% of households in Orania, followed by unaffiliated households with 15.6%, the Dutch Reformed Church and the Maranatha Church (both 14.8%), Gereformeerd Church (7.4%). In total, 84.4% of households are affiliated with a religion.[2]

The Afrikaanse Protestantse Kerk was established in 1991,[68] making it the first church to be established in Orania.[69] The congregation counts 145 members.[68] The church is a prefabricated building,[70] the only church in Orania with a steeple.[71]

The Dutch Reformed Church in Orania was established in 1999, when it detached from the Hopetown congregation.[69] The church is part of the ring (presbytery) of Hopetown and the synod of the Northern Cape.[72] In March 2015, the Dutch Reformed Church in Orania voted against changes to the DRC Church Order allowing for the adoption of the Belhar Confession, as did a majority of churches in the Northern Cape Synod.[73]

Subdivisions and architecture

Orania has three residential areas: Kleingeluk ("small happiness"), Grootdorp ("big town") and Orania Wes ("Orania West").[15] Kleingeluk is a separate district about 1.5 km away from Grootdorp, and is poorer than the main town, although progress has been made in narrowing the gap in living conditions.[74]

Many houses in Orania are built in the Cape Dutch architectural style.[3] Most of the original buildings from the water department era are prefabricated, and while some have been renovated others show sign of deterioration, as they weren't designed to last for more than 20 years.[75]

Politics and administration

The OVR (Orania Verteenwoordige Raad/ Orania Representative Council) is the highest democratic institution in Orania and Carel Boshoff is the chairman (Mayor) of the OVR.

VAB (Vluytjiekraal Aandele Blok / Vluytjiekraal Share Block) is currently responsible for running the daily affairs. It is elected annually, and consists of five members and a chairman.[76] Political parties are not allowed in Orania's local elections.[77] The budget for the fiscal year 2006/2007 was R2.45 million.[78] The Orania Beweging (Orania Movement) is a separate political and cultural organisation that promotes Afrikaner history and culture.[76] The Orania Movement has around 3,000 registered supporters from outside town.[79]

Orania receives no fiscal contributions from either state or provincial government.[80] The Helpsaam Fund, a non-profit institution, raises money for projects like subsidised housing for newcomers in need.[37] The Elim Centre accommodates unemployed young men who come to Orania seeking employment. Most are destitute when they arrive.[81] They are usually given work with the municipality or local farms, and provided with training.[82] Nerina, the equivalent residential complex for women, was completed in July 2012.[83]

The town has neither a police force nor a prison.[84] Traffic monitoring and minor crimes such as petty theft are handled internally.[85] Neighbourhood watch patrols are carried out by volunteers.[85] In October 2014 Orania Veiligheid (Orania Security) was established, to handle reports of illegal activities such as drug dealing or car theft, but also more trivial matters such as littering and noise complaints. Apprehended suspects are taken to the police station in neighbouring Hopetown.[86] Residents are exhorted to use mediation and arbitration procedures made available by the town council, rather than resorting to South African courts.[37]

Orania has a small clinic, and a government-funded nurse visits twice a month.[80] The town has two airstrips, one 1,300m and the other 1,000m.[87]

Legal framework

Orania is part of the Thembelihle municipal area, but by mutual agreement the municipality provides no services (like sewerage, roads, rubbish collection)[88] and collects no rates from the town (other taxes are paid normally).[89][82]

The town is privately owned by the Vluytjeskraal Aandeleblok company. Ownership of plots and houses is in the form of shares in the company,[37] according to a framework known as share block under South African law, similar to the strata title or condominium in other countries.[36] No title deeds are provided, except for agricultural land.[90]

Vluytjeskraal functions like a municipal administration, being funded by rates and delivering services like water, electricity and waste management.[37] Utility companies like Eskom and Telkom provide services to this private entity, which then splits the costs and charges the end users.[88]

Application process

Prospective residents are required to go through an interview process with a committee, which may deny access to people based on criteria such as criminal records.[84] Once permission is granted, the new residents become shareholders in the town.[84]

Being an Afrikaner is the most important criterion for admission.[3] Most news sources report that black or coloured people are not allowed to live in Orania,[15] although Boshoff said that Jakes Gerwel and Neville Alexander (Coloured anti-apartheid activists) would be welcome to settle in the town, if they wished to do so.[91] In 1990, Orania's founder defined the Afrikaner nation in cultural, rather than racial, terms.[92] The town's spokesman similarly insists that there are no rules against allowing an Afrikaans-speaking coloured person to live in Orania.[79]

Some people who try to live in Orania ultimately leave due to the limited choice of available jobs or the requirement to conform to local social norms.[34] According to a 2004 study, 250 people had left Orania since its establishment in 1991, most of them due to "physical and social pressure".[93] The difference in lifestyle compared to an urban environment is another factor that negatively impacts newcomers.[94]

Environmental practices

Town authorities have a strong focus on green practices, including recycling and conservation.[8] Recycling is compulsory for all households, and residents sort their own waste place it into five different rubbish bins. Solar geysers are a requirement for all new houses built in Orania. Examples of green architecture can be seen throughout town, including houses built with materials such as stone, wood and hay.[16]

An earthship (aardskip) is currently being built in Orania.[95] It was designed by Christiaan van Zyl, one of South Africa's foremost experts on sustainable architecture.[96] The building is unfinished as of 2015; once completed it will be the largest earthbag earthship in the world.[96]

In 2014 Orania opened its bicycle sharing system, called the Orania Openbare Fietsprojek (Orania Public Bicycle Project).[97]

External relations

The town's existence is allowed by the Constitution of South Africa under a clause that allows for the right to self-determination.[3] Orania has a non-confrontational attitude towards South African authorities, which have likewise adopted a non-interference policy towards Orania.[98] The ANC government mostly avoids the issue of Orania and its status, as it is seen as less important than many other political issues the party has to confront.[99]

On 5 June 1998, Valli Moosa, then Minister of Constitutional Development in the ANC government, stated in a parliamentary budget debate that "the ideal of some Afrikaners to develop the North Western Cape as a home for the Afrikaner culture and language within the framework of the Constitution and the Charter of Human Rights is viewed by the government as a legitimate ideal".[11]

Dipuo Peters, then Premier of the Northern Cape, visited the town in July 2004. Peters said she was impressed with how development takes place in the community.[100] On 4 July 2007 the town of Orania and the Northern Cape government agreed that the question of Orania's self-government should be discussed at all government levels.[101]

In 2009, an African National Congress Youth League delegation visited the town. The leader Julius Malema praised the co-operation between residents: "they co-operate instead of working against each other".[102] On 14 September 2010 President Jacob Zuma visited Orania, meeting its founder Carel Boshoff and his son, Orania mayor Carel Boshoff IV and other community leaders. After the meeting Zuma visited housing projects and several agricultural sites in Orania.[103]

In June 2007, the Afrikaner enclave was visited by the Coloured community of Eersterust, outside Pretoria.[104] The groups met to discuss community development and discussed methods of self-governance. According to visitors the reception was good, and they had "definitely learned from the experience" and experienced no racial tension. The community of Orania gave a donation to the community of Eersterust in support of their nursery school.[104]

Orania and the Xhosa community of Mnyameni signed a cooperation agreement on 11 December 2012. The objective of the agreement is to assist in the development of own institutions and the transfer of knowledge between the communities in order to reduce their dependency on government initiatives for development.[105][106]

Members of the Orania Beweging, including its president Carel Boshoff, went on a European tour in 2013, meeting with MPs from the Partij voor de Vrijheid of the Netherlands, the Vlaams Belang party in Belgium and Südtiroler Volkspartei in Italy's South Tyrol province.[107][108]

The largest right-wing party in apartheid-era South Africa, the Conservative Party, did not support the volkstaat concept until 1993, shortly before converging with other right-wing organisation into the Afrikaner Volksfront.[109] Even then, their plan involved separating parts of Transvaal Province, including Pretoria, to form a state where the many black residents would have only limited voting rights.[109] Negotiations to this end were conducted with the ANC, but were ultimately inconclusive.[110] The last white-minority government led by F. W. de Klerk was also opposed to the creation of an Afrikaner state and the existence of Orania, but took no action against it, believing it would fail on its own.[111]

Debate surrounding a volkstaat returned to the mainstream media following the murder of AWB leader Eugene Terre'Blanche in April 2010. Boshoff claimed a symbolism of the murder for farm murders that he described as "nothing other than a state of war". Yet, he rejected an invitation to Terre'Blanche's funeral, "I'm not enamoured of him. He chose a path of confrontation, of conflict. We wanted another way."[112] Boshoff IV also noted that the Orania concept was at odds with the baasskap system of the apartheid period.[25]

Prior to the 2016 local elections, the Thembelihle branch of the Economic Freedom Fighters campaigned on a platform including a pledge to terminate the autonomous status of Orania, if elected to govern the municipality.[88] The party ultimately won 11.6% of the municipal vote.[113]

Election results

Since 1994, citizens of Orania have voted all five times in the national elections. Over the last three elections, Orania had an average vote turnout of 65%, based on registered voters. In the South African general election, 2009, the community decisively voted for the Freedom Front Plus party.[114] The four votes recorded for the Economic Freedom Fighters party in the 2014 election elicited a number of comments from South African media.[115]

| Party | Votes (2004[116]) | % (2004) | Votes (2009[114]) | % (2009) | Votes (2014[117]) | % (2014) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freedom Front Plus | 158 | 84.95% | 242 | 86.73% | 224 | 76.89% |

| Democratic Alliance | 16 | 8.60% | 26 | 9.31% | 44 | 15.12% |

| African Christian Democratic Party | 3 | 1.61% | 3 | 1.07% | 7 | 2.41% |

| African National Congress | 3 | 1.61% | 3 | 1.07% | 5 | 1.72% |

| Congress of the People[lower-alpha 1] | - | - | 3 | 1.07% | 1 | 0.34% |

| National Action[lower-alpha 2] | 3 | 1.61% | - | - | - | - |

| Independent Democrats[lower-alpha 3] | 2 | 1.08% | 0 | 0% | - | - |

| New National Party [lower-alpha 4] | 1 | 0.54% | - | - | - | - |

| Economic Freedom Fighters [lower-alpha 5] | - | - | - | - | 4 | 1.37% |

| Front National[lower-alpha 5] | - | - | - | - | 4 | 1.37% |

| Ubuntu Party[lower-alpha 5] | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0.69% |

| Spoilt votes | 2 | 1.08% | 2 | 0.71% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Total | 188 | 100.00% | 279 | 100.00% | 291 | 100% |

- Notes

- ↑ Party did not contest in elections before 2009.

- ↑ Party only contest in the 2004 elections and then submerged into the Freedom Front, making it the Freedom Front Plus

- ↑ Merged into the Democratic Alliance in 2012.

- ↑ Merged into the African National Congress in 2005.

- 1 2 3 Party did not contest in elections before 2014.

Economy and agriculture

Farming is an important part of Orania's economy, the most prominent project being a massive pecan nut plantation,[118] one of the largest in South Africa.[59] The plantation is said to have given Orania a substantial economic boost.[119] Most of the agricultural production is exported to China.[14] Since purchasing the 430 hectares (1,100 acres) town, the community has added 7,000 hectares (17,000 acres) of agricultural land to the town.[120] A pumping station on the Orange River, financed and built by the town's residents, provides water for agricultural use.[100] The station is connected to a 9 km pipeline.[28]

More than 100 businesses are located in Orania as of 2013.[14] Economic services provided in the town include a call centre, stockbroking and architecture.[84] The community's annual turnover in 2011 was R48 million.[121] Property prices in 2010 ranged from R250,000 at the low-end, up to R900,000 for new riverfront property.[122] Average house prices in Orania have grown by 13.9% a year from 1992 to 2006.[123]

Orania's tourism industry is showing rapid development with the completion of a luxury river spa and boutique hotel complex in 2009.[124] Orania Toere (Orania Tours), Orania's first registered tour operator, was also launched in 2009. In 2010 thirteen independent hospitality businesses operate in Orania.[125] This includes a caravan park, self-catering flats, rooms, hotel and guest-houses. The town is said to be popular among black tourists.[8] From October 2012 to February 2013, about 2,000 holidaymakers visited the town.[126]

In Orania people from all levels of society perform their own manual labour.[15] Local Afrikaners also work in unskilled positions such as gardening and waste collection.[63] Rapid growth over the four years to 2014 led to the construction of new commercial developments and a rising number of young adult immigrants, but also caused an increase in class differences between residents.[127] The average wage in Orania was estimated at approximately R4,000 per month in 2007, low by white South African standards.[128] The lack of cheap black labour means that living expenses in Orania are twice as high as in the rest of South Africa;[79] at the same time, unskilled workers are scarce.[81] In 2009, 14% of the population was self-employed.[129]

During April 2004, Orania launched its own monetary system, called the Ora, based on the idea of discount shopping vouchers.[10] The Orania local banking institution, the Orania Spaar- en Kredietkoöperatief (Orania Savings and Credit Co-operative) is in charge of this initiative. Orania launched its own chequebook in 2007.[130] The use of the Ora as a payment method also has the effect of discouraging theft, as it can only be used within Orania.[131] About R400,000 to R580,000 worth of Oras were in circulation by 2011.[22] New notes are printed every three years to replace the ones worn out by use. The E-series was distributed in April 2014.[132]

A R9 million dairy farm, the Bo-Karoo Suiwel, operated in Orania from 1998 to 2002. Though deemed one of the most modern dairies in South Africa at the time,[34] the increased cost of imported machinery caused by a decline in value of the rand combined to a rise in the price of corn used to feed cattle led to its liquidation.[133][134] Another ambitious project, a mill processing a range of corn products, was completed in 2005,[135] but proved similarly unsuccessful and was closed down.[136] The Orania management has since mostly eschewed large-scale projects, rather focussing on small- and micro-enterprises to develop the local economy.[136]

Culture

Cultural institutions include the Orania Kunsteraad met orkes en koor (arts council with orchestra and choir) and the Orania Kultuurhistoriese museum (cultural history museum).[78] Exhibits housed in the museum include the Felix Lategan gun collection and a Vierkleur flag carried by Jopie Fourie.[137] A collection of busts of Afrikaner leaders, sourced from institutions that no longer wanted them after the end of apartheid, sits on a 'monument hill' outside town.[59] There is also a Verwoerd museum, in which items and photos of Hendrik Verwoerd are on display.[59]

The Koeksistermonument, erected in 2003, celebrates the koeksister and is one of the town's tourist attractions.[138] The town also houses the Irish Volunteer Monument, dedicated to the Irish soldiers who fought on the Boer side during the Boer War (see Boer foreign volunteers).[59] The monument was designed by Jan van Wijk, who also created the Afrikaans Language Monument in Paarl. It was moved from Brixton, Gauteng in 2002 by a group of Afrikaners concerned by its imminent demolition.[59]

Orania has a mascot named Kleinreus (small giant), a small boy shown rolling up his sleeves.[59] The symbol is used for the town's flag, its currency and merchandise.[83] Traditional Afrikaner cultural activities such as volkspele dances and games of jukskei are promoted within the community.[139] Karoo-style food such as skaapkop is part of the local culinary heritage.[139] The town has a rugby team, the Orania Rebelle, playing in the Griqualand West Rugby Union.[140]

The Orania Karnaval (formerly Volkstaatskou) is the main cultural event in town. Held annually since April 2000,[141] it features exhibitions, competitions and concerts from local artists,[142] with food stalls offering traditional Afrikaner treats.[143] The Ora currency and the Kleinreus flag were both introduced during the celebrations.[144][145]

Younger residents occasionally complain of a lack of recreational activities, a concern common to many small communities.[146] Orania, a farming town, offers few amusements to teenagers and young adults, who miss the entertainment offered by city life.[147] Quad racing is a popular pastime, but frowned upon by town authorities for safety reasons.[148] The Bistro was a popular hangout for the youth of Orania, but it ceased operations after the owner died in 2009.[149] Two notable businesses are the Wynhuis (a liquor store) and the Vaatjie (a pub). The Wynhuis is visited not only by locals, but also coloureds from neighbouring farms. The Vaatjie is a contentious place among members of the community, as it is seen as a place of loose mores, and fights occasionally break out between patrons; the Vaatjie burned down in 2009 and was reopened in 2011.[150]

Education

There are two schools, the CVO Skool Orania (Christelike Volks-Onderwys or Christian People's Education) and Volkskool Orania (Orania People's School). Afrikaans is the language of instruction, while English is taught as a second language.[151] Both schools follow the IEB curriculum,[152] with special emphasis placed on Afrikaner history and Christian religion, though with some differences in their teaching methods.[153]

The CVO-school, established in January 1993,[40] is run along conventional lines;[154] enrolment in 2014 was 225 students, with some coming from neighbouring towns.[155] The Volkskool use a self-driven teaching (selfgedrewe) system which is unorthodox by South African standards.[156] It was established in June 1991, with Julian Visser as its first principal.[40]

There is a rivalry between the schools, which is generally friendly but can occasionally become quite fierce.[157] Not all local children attend them, as some parents choose homeschooling or boarding schools in cities like Bloemfontein.[66]

All educational activities in Orania are supervised by the Orania Koördinerende Onderwysraad.[158] Orania's schools have consistently achieved a 100% matric pass rate since 1991.[159]

Media

The first local community radio, Radio Club 100, was shut down by Independent Communications Authority of South Africa in November 2005 for broadcasting without a licence and being a "racist-based station".[160] Management of the radio station contended they had repeatedly applied for a licence and were merely carrying out tests, and that they broadcast harmless news about birthdays and social events.[160] Icasa granted a licence to the new Radio Orania in December 2007,[161] and the station started broadcasting on 13 April 2008 on 95.5 MHz.[162] The community station is run by volunteers and counts over 50 contributors.[163] Programmes include readings of Afrikaans literature such as Mikro's Die ruiter in die nag.[164]

Dorpnuus, the town hall's newsletter, was launched in November 2005 and reports on local events and meetings of the town council.[165] Volkstater is an independent local publication that is sent to supporters of the volkstaat idea, mostly non-residents of Orania. and deals with local events and Afrikaner history.[166] Voorgrond, a publication of the Orania Beweging, is primarily aimed at non-residents who support the movement.[167]

Cultural holidays

_(2).jpg)

Geloftedag on 16 December is one of the most important holidays for the community. Locals wear traditional clothing and commemorate the victory in 1838 of 470 Afrikaners over an army of 15,000 Zulu warriors.[168]

A list of cultural holidays in Orania:[169]

| Date | Afrikaans Name |

|---|---|

| 27 February | Majubadag |

| 6 April | Stigtingsdag |

| 31 May | Bittereinderdag |

| 14 August | Taaldag |

| 10 October | Heldedag |

| 16 December | Geloftedag |

Reception

The community receives a high number of visits from local and international media organizations,[52] so that Oranians are constantly in contact with journalists.[170] The very existence of Orania as a homogeneously Afrikaner town is controversial, and news sources portray it as culturally backward and racially intolerant.[31] Orania is generally talked about as racist and separatist place.[171] In 1994 the Los Angeles Times described it as "one of [South Africa's] strangest towns" and "a bastion of intolerance".[172] A year later the Chicago Tribune saw it as "the last pathetic holdout of the former ruling class of South Africa", continuing that "the Afrikaners who once forced blacks to live apart from the rest of society are now living in their own prison".[173] A Mail & Guardian article describes it as a 'widely ridiculed town' and a 'media byword for racism and irredentism'.[174] An article in The Independent similarly notes that residents of Orania have a reputation for being racists, and that the town attracts plenty of negative press.[175]

One commentator noted the diverging perceptions of the town between white liberals and blacks: the former see it as a "pathetic outpost of embittered racists", refusing to live in equality with black South Africans; the latter see it as a 1950s-style fantasy shielding locals from declining white privilege.[176] Orania was deemed to lack privilege, however, as residents have no domestic workers and few material luxuries; white suburbs in the rest of South Africa, with their high levels of segregation and heavy use of domestic labour, were felt to more closely resemble the apartheid era than Orania did.[176] Along similar lines, Orania was also seen as "one of the few places in South Africa ... where class is not determined by skin colour".[177] Another journalist found comparisons of Orania to the apartheid system inappropriate, as town authorities do not seek to exploit or subjugate blacks, but simply demand separation.[151] In its obituary of Orania's founder Carel Boshoff, Foreign Policy magazine agreed with Boshoff's proposition that the position of white South Africans as a privileged class dependent on black labour is untenable.[178]

In September 2012, a German documentary film titled Orania premiered at London's Raindance Film Festival. The film is a sociological study of the town.[179] The town was also featured in a 2009 documentary produced by France Ô, Orania, citadelle blanche en Afrique.[180][181]

Orania is mentioned in one of the leaked American diplomatic cables, relating details of a 2004 visit to the town, where it is described as a "sleepy country town with few signs of growth or vitality".[182]

Afrikaner reception

Most Afrikaners do not support the establishment of an Afrikaner state,[151] as they see it as nothing more than an impractical pipe dream,[183] though a survey of Beeld readers carried out in 2010 found that 56% of respondents would consider moving to a volkstaat.[184] Shortly after the first residents moved in in 1991, the project was derided by many whites as unrealistic,[185] with even right-wingers rejecting it for being located in such barren territory, far from traditional Afrikaner states.[186] Orania and its leadership are poorly regarded by the Afrikaner far-right, as their official stance of opposing racism is said to be seen by them as excessively liberal.[187]

In 2010 Marida Fitzpatrick, journalist for the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger, praised the town for its safety and environmentally friendly approaches to living, but also wrote that overt racist ideas and ideology still underpinned the views of many residents.[188] Members of the AfriForum group who visited Orania in February 2015 came back with mostly positive impressions of the town, comparing it to a Clarens or Dullstroom of the Karoo.[97] Afrikaans singer Steyn Fourie is a supporter of Orania,[189] and wrote a song about the town.[190]

In January 2010, Afrikaans daily newspaper Beeld published an article by Frans de Klerk, chief executive of Orania, in which he sets out what he views as the successes of Orania.[191] De Klerk also distanced the town from racist organizations using Orania to further their own causes.[191]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Main Place "Orania"". Census 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sosio-ekonomiese opname – Orania sensus 2014" (PDF) (in Afrikaans). Orania Dorpsraad. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fihlani, Pumza (6 October 2014). "Inside South Africa's whites-only town of Orania". BBC News. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Haleniuk 2013, p. 4.

- ↑ "DVD". Orania. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ Standley, Jane (16 December 2000). "Rainbow nation at risk?". BBC News. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Daley, Suzanne (4 May 1999). "Orania Journal; Afrikaners Have a Dream, Very Like the Old One". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Louw, Poppy (29 April 2014). "20 years of democracy in Orania: The past might have a future". Times LIVE. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Leboucher, Quentin (8 May 2013). "We're not racists, say Orania residents". IOL News. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- 1 2 "'Whites-only' money for SA town". BBC News. 29 April 2004. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- 1 2 Bezuidenhout, Nick (5 June 1998). "VF se strewe legitiem, sê Moosa" [Freedom Front endeavour legitimate, says Moosa] (in Afrikaans). Beeld.

- 1 2 Davis, Rebecca (16 May 2013). "Orania: The place where time stood still". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Tandwa, Lizeka (7 June 2016). "EFF meets with Orania leaders". News24. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Haleniuk 2013, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 "10 years on, Orania fades away". News24.com. 22 April 2004. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Orania - Home of the Afrikaner". Lief-orania.co.za. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ Groenewald, Yolandi (1 November 2005). "Orania, white and blue". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schonteich & Boshoff 2003, p. 44.

- ↑ Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2008). South Africa in Contemporary Times. Intercontinental Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-9802587-3-8.

- 1 2 Buncombe, Andrew (13 December 2013). "We shed no tears for Nelson Mandela. He is a fallen opponent, say residents of white enclave Orania". The Independent. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Schonteich & Boshoff 2003, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Voorgrond" (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- 1 2 Parks, Michael (11 October 1986). "Form Afrikaner Nation, Rightist Urges". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Schonteich & Boshoff 2003, p. 39.

- 1 2 Donaldson, Andrew (25 April 2010). "All white, and a bit green, in the far country". Times LIVE. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Christopher, A.J. (4 January 2002). Atlas of Changing South Africa. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-134-61674-9.

- ↑ Schonteich & Boshoff 2003, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Opperman, M. "The Residential Development on the Farm Vluytjes Kraal Noord, Orania". South African Heritage Resources Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Opperman, Manie (August 2011). "The Vermeulen Engravings: Binding Six Afrikaner Generation". EBSCO Online Library. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- 1 2 Haleniuk 2013, p. 3.

- 1 2 Delvecki, Ajax; Greiner, Alyson (22 December 2014). "Circling of the Wagons?: A Look at Orania, South Africa". HighBeam Research. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 Pienaar 2007, p. 57-58.

- 1 2 3 Pienaar 2007, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 McGreal, Chris (29 January 2000). "A people clutching at straws". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Impact on Cultural Heritage Resources" (PDF). Eskom Holdings Limited. August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- 1 2 Cavanagh, Edward (23 April 2013). Settler Colonialism and Land Rights in South Africa: Possession and Dispossession on the Orange River. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 69–75. ISBN 978-1-137-30577-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Boshoff, Carel (7 October 2014). "Orania and the third reinvention of the Afrikaner". Politicsweb. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- 1 2 Pienaar 2007, p. 59.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Pienaar 2007, p. 60.

- ↑ "Orania lets election happen - but won't vote". IOL News. 1 December 2000. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Pienaar 2007, p. 59-60.

- ↑ Daley, Suzanne (23 March 1999). "Beloved Country Repays Mandela in Kind". New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ "Orania, Main Place 31202 from Census 2001". Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "Millions of rands already invested in Orania". Orania.co.za. May 1998. Archived from the original on 1999-04-20. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Man in hof ná Orania-skietery" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. 20 April 2000. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Butcher, Tim (25 November 2000). "Black mayor to destroy dream of white homeland". Telegraph. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Mufamadi meets Orania representatives". News24. 12 March 2001. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ "Orania and N Cape govt to discuss future of enclave". Mail & Guardian. 4 July 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Orania retains status quo". News24. 5 December 2000. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Van Der Merwe, Hannatjie (9 May 2005). "'Mafia' regeer glo Orania" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- 1 2 Hagen 2013, p. 128.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ Groenewald, Yolandi (18 November 2005). "Coloureds Claim the Volkstaat". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 25 June 2006.

- ↑ "Orania Pleased at Land Claim". News24. 5 December 2006. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Nuwe winkelsentrum vandag in Orania geopen" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. 13 June 2006. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ "Voorgrond" (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. September 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ "Voorgrond" (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. March 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sosibo, Kwanele (13 November 2014). "Brixton to Orania: The great trek of the Irish Volunteer Monument". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- 1 2 Hagen 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 161.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 114.

- 1 2 "Where even street sweepers are white". IOL News. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 195.

- ↑ Pienaar 2007, p. 62.

- 1 2 Hagen 2013, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Hagen 2013, p. 64.

- 1 2 "Hoe die Afrikaanse Protestantse Kerk van Orania ontstaan het" (in Afrikaans). OraNet. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Orania het ook nou 'n NG gemeente" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. 14 September 1999. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ "As ons maar net vir Pappa geluister het" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 48.

- ↑ "NG Kerk Orania" (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Mailovich, Claudi (10 March 2015). "Belhar: Orania se NG kerk sê nee vir wysiging" (in Afrikaans). Netwerk24. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Haleniuk 2013, p. 4-5.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 52.

- 1 2 Haleniuk 2013, p. 5.

- ↑ "Insight into Orania". Südafrika-Portal. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- 1 2 Pienaar 2007, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 Scheen, Thomas (1 June 2013). "In der Wagenburg" (in German). Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- 1 2 Hagen 2013, p. 55.

- 1 2 Barnard, Phillippa (2 February 2008). "Groot gaping tussen ryk en arm kan Orania se nuwe visie verdof" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- 1 2 Grobler, Andre (10 September 2010). "Zuma's visit 'an outstanding day' for Orania". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 Haleniuk 2013, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 Craw, Victoria (1 November 2014). "Orania: South Africa's last apartheid town". News.com.au. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- 1 2 Hagen 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Kemp, Charné (21 October 2014). "'Klakantoor' in Orania" (in Afrikaans). Netwerk24. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Millner, Caille (29 January 2008). The Golden Road: Notes on My Gentrification. Penguin. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-14-311297-6.

- 1 2 3 de Wet, Phillip (5 August 2016). "Orania held its own election this week, buoyed by a vision of growth and prosperity". Maili & Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Strydom, John (24 May 2011). "Verkiesing-die ware storie" (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Van Zyl Slabbert, Frederik (2006). The Other Side of History: An Anecdotal Reflection on Political Transition in South Africa. Jonathan Ball. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-86842-250-0.

- ↑ Adam, Heribert; Moodley, Kogila (1993). The Opening of the Apartheid Mind: Options for the New South Africa. University of California Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-520-08199-4.

- ↑ Pretorius, Liesl (4 November 2004). "Afrikaners in Orania is 'anders'" (in Afrikaans). Die Burger. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 156.

- ↑ "Project Aardskip". Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- 1 2 Leckert, Oriana (18 March 2015). "Way Off The Grid: 6 Earthships That You Should Know". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- 1 2 van den Heever, Juran (23 February 2015). "Orania – Nie so 'n vergesogte droom nie" (in Afrikaans). AfriForum. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Veracini, Lorenzo (2011). "Orania as Settler Self-Transfer". Settler Colonial Studies. 1 (2). doi:10.1080/2201473X.2011.10648821. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Edward Cavanagh (2013-04-23). Settler Colonialism and Land Rights in South Africa: Possession and Dispossession on the Orange River. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-137-30577-0.

- 1 2 Van Wyk, Joylene (31 July 2004). "Orania kan N-Kaap help, sê premier" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ "Orania, N Cape agree on way forward". IOL News. 4 July 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ "Malema surprised by Orania". News24. 28 March 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "Jacob Zuma visited Orania". News 24. 14 September 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Orania community lauded". News24.com. 11 June 2007. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- ↑ "Orania signs agreement with Mnyameni". Mail & Guardian. 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Boshoff, Carel (2 January 2013). "Maak soos vriende". Beeld (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ↑ Buren zu Gast bei Südtiroler Volkspartei, abgerufen am 25. Oktober 2015

- ↑ Kromhout, Bas (10 May 2013). "PVV-fractie ontvangt Afrikaner separatisten" (in Dutch). Historisch Nieuwsblad. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- 1 2 Pienaar 2007, p. 45.

- ↑ Pienaar 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Moutout, Corinne (18 March 1991). "Les Afrikaners "pure souche" rêvent d'une patrie indépendante et ont déjà créé "Orania"" (in French). Le Soir. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ↑ Donaldson, Andrew (10 April 2010). "Orania building a different future". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2010-04-17. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "Local Government Elections 2016". News24. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Orania votes for FF+". IOL News. 23 April 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "'No problem with EFF votes in Orania'". IOL News. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ "2004 National Results". News24. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ↑ "2014 National Results". News24. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Dicey, William (1 September 2007). Borderline. Kwela Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7957-0189-4.

- ↑ Booyens, Hannelie (18 July 2013). "Orania: The town that time forgot". City Press. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ Du Plessis, Carien (29 March 2009). "Zuma likely to visit Orania". IOL News. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Amos, Phago (18 October 2011). "Orania to complete Census before deadline: Tuesday". SABC News. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ Haynes, Gavin (19 January 2010). "Orania: The Little Town that Racism Built". VICE. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Kloppers, Elma (13 June 2006). "Ekonomie van Orania gaan van krag tot krag" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Orania Oewerhotel en Spa". Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Flitslig, Mei 2010 and Voorgrond, 2010

- ↑ Haleniuk 2013, p. 10-11.

- ↑ Sosibo, Kwanele (12 November 2014). "Orania: Afrikaner dream gives capitalism a human face". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 111.

- ↑ Mears, Ronald. "The Ora as facilitator of sustainable local economic development in Orania".

- ↑ "Orania launches own cheque book". iAfrica. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-03-08.

- ↑ "Wo Afrikaaner unter sich bleiben können" (in German). Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 23 January 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Strydom, John (10 March 2014). "Nuwe reeks Oras oopgebreek" (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ "Melkery in Orania lewer melk vir kaas" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. 30 December 1998. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Chris (24 February 2002). "Orania-melkery se geldspeen droog op" (in Afrikaans). Rapport. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Orania se meule vroeg volgende jaar in bedryf" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. 3 December 2004. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- 1 2 Boshoff, Wynand (8 March 2013). "Die verdigting en uitbreiding van Orania" (in Afrikaans). Vry Afrikaner. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Versluis, Jeanne-Marié (15 April 2000). "Dorp sal 10 000 mense kan huisves" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ↑ Haleniuk 2013, p. 9.

- 1 2 Naudé-Moseley, Brent; Moseley, Steve (2008). Getaway Guide to Karoo, Namaqualand & Kalahari. Sunbird. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-919938-58-5.

If you want to taste regte egte (real genuine) Afrikaans culture, arrange a visit to Orania during one of their special occasions when they'll host traditional dancing, volkspele (games) such as jukskei (yoke-pin) and eat skaapkop (traditional ...

- ↑ Malan, Marlene (22 April 2013). "Olé, olé, olé, Orania!" (in Afrikaans). Rapport. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 154-155.

- ↑ "Orania hou Volkstaatskou" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. 12 March 2003. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Coetzee, Frans (29 April 2005). "Orania se geldeenheid op Volkstaatskou herdenk" (in Afrikaans). Volksblad. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Van Der Merwe, Hannatjie (23 February 2004). "Orania kry glo einde April eie geldeenheid by volkskou" (in Afrikaans). Die Burger. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 113.

- ↑ Six, Billy (4 June 2010). "Im Schutz der Wagenburg" (in German). Junge Freiheit. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, pp. 111-112.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 125.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 72-73.

- 1 2 3 Kirchick, James; Rich, Sebastian (1 July 2008). "In Whitest Africa". VQR Online. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ du Plessis, Jaco (24 May 2014). "Hammond het helder lens op Orania gerig" (in Afrikaans). LitNet. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ "Skole". Orania. Archived from the original on 2009-09-30. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ "Orania CVO-skool". Oraniacvo.co.za. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ "Bloudruk" (in Afrikaans). Orania CVO. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Red Apple Media. "Afstandleer Plus". Afstandsleer.co.za. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 62.

- ↑ Pienaar 2007, p. 71.

- ↑ "The journey to hell and back". IOL Travel Western Cape. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Orania radio station kicked off the air". IOL News. 9 November 2005. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Radio Orania gets green light from Icasa". Mail & Guardian. 4 December 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Radio Orania on-air again". SABC News. 13 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ "Orania Beweging". Twitter. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 148.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 165-166.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 158.

- ↑ Tweedie, Neil (13 December 2013). "Orania: the land where apartheid lives on". Telegraph. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "Voorgrond" (PDF) (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. February 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Hagen 2013, p. 211.

- ↑ Musekwa, Rudzani Floyd (20 May 2014). "Is Orania a racist enclave, or a misunderstood cultural concept?". The New Age Online. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Drogin, Bob (28 February 1994). "Zealots' Dream Falters in Whites-Only S. Africa Town : Racism: Bastion of intolerance sees itself as model. But glimpse of future disappoints some separatists". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Szechenyi, Christopher A. (30 March 1995). "A Segregated Town Survives In South Africa". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Nikitin, Vadim (16 September 2011). "Bigotry without racism? -- Lessons from Orania". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Schadomsky, Ludger; Collins, Charlotte (10 December 2003). "Apartheid's last stand". The Independent. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- 1 2 Nikitin, Vadim (15 April 2011). "Inside South Africa's last bastion of apartheid". The National. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Orania - endast för vita" (in Swedish). Sveriges Radio. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Fairbanks, Eve (23 March 2011). "Death of a True Afrikaner Believer". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Bowman, Dean. "Orania". Raindance Film Festival 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "Orania, citadelle blanche en Afrique". Africultures. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Martin, Eric (4 July 2011). "Orania, cité blanche d'Afrique du Sud". Nouvelles de France. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Embassy Pretoria (21 December 2004). "Cable 04PRETORIA5466, Cloud Cuckoo-land's Last Redoubt: A Visit To Orania". Wikileaks. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ De Beer, F.C. (2007). "Exercise In Futility, Or Dawn Of Afrikaner Self-determination: An Exploratory Ethno-historical Investigation Of Orania". Eastern Michigan University. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ du Toit, Pieter (13 January 2010). "Volkstaat hou g'n heil in" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ S. Wren, Christopher (8 May 1991). "A Homeland? White Volk Fence Themselves In". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Sly, Liz (16 March 1992). "'All-White' Town Finds It Can't Live Without Blacks". Seattle Times. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Masilela, Johnny (27 September 2015). "Orania leader true racists love to hate". Sunday independent. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Marida (30 January 2010). "Ook net mens". Die Burger (in Afrikaans). Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "Helpsaamfondsdinee saam met Steyn Fourie ten bate van die Elim steen vir steen Projek" (PDF) (in Afrikaans). Orania Beweging. May 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ Tobias Lindner. Orania (audio commentary) (in German and English). VHX. Event occurs at 53:35.

- 1 2 de Klerk, Frans (20 January 2010). "Hiér is anderkant die kla 'n Tuiste vir diegene wat hul eie lot bestuur" (in Afrikaans). Beeld. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

References

- Hagen, Lise (January 2013), Place of our own: The Anthropology of Space and Place In the Afrikaner Volkstaat of Orania (PDF), Pretoria: University of South Africa, retrieved 1 April 2015

- Haleniuk, Aleksander (October 2013), Orania – the embryo of a new Volkstaat?, Uniwersytet Warszawski, retrieved 25 August 2014

- Schonteich, Martin; Boshoff, Henri (2003), `Volk` Faith and Fatherland. The Security Threat Posed by the White Right (PDF), Institute for Security Studies, retrieved 5 January 2014

- Pienaar, Terisa (March 2007), Die aanloop tot en stigting van Orania as groeipunt vir 'n Afrikaner-volkstaat (PDF) (in Afrikaans), Universiteit van Stellenbosch, retrieved 4 April 2015

External links

- Official website of Orania (in Afrikaans)

- Issues of Voorgrond, the town's newsletter

- Ripping the rainbow – eNCA CheckPoint feature on the town (December 2014)

- Orania - a place to live – M-Net story about the Volkskool (October 2002)

|

Orange River | Belmont | Koffiefontein |  |

| Strydenburg | |

Luckhoff | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Kraankuil | Philipstown | Petrusville |

.svg.png)