Og

.jpg)

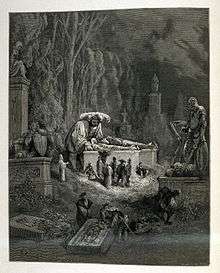

Og (Hebrew: עוֹג, ʿog ˈʕoːɡ; Arabic: عوج, cogh [ʕoːɣ]) according to The Torah, was an Amorite king of Bashan who, along with his army, was slain by Moses and his men at the battle of Edrei. In Arabic literature he is referred to as ‘Uj ibn Anaq (‘Ûj ibn ‘Anâq عوج بن عنق).

Og is mentioned in Jewish literature as being one of the very few giants that survived the Flood.

Og is introduced in the Book of Numbers. Like his neighbor Sihon of Heshbon, whom Moses had previously conquered at the battle of Jahaz he was an Amorite king, the ruler of Bashan, which contained sixty walled cities and many unwalled towns, with his capital at Ashtaroth (probably modern Tell Ashareh, where there still exists a 70-foot mound).

The Book of Numbers, Chapter 21, and Deuteronomy, Chapter 3, continues:

- "Next we turned and went up along the road toward Bashan, and Og king of Bashan with his whole army marched out to meet us in battle at Edrei." Moses speaks: "The LORD said to me, "Do not be afraid of him, for I have handed him over to you with his whole army and his land. Do to him what you did to Sihon king of the Amorites, who reigned in Heshbon ... So the LORD our God also gave into our hands Og king of Bashan and all his army. We struck them down, leaving no survivors." ... "At that time we took all his cities, there was not one of the sixty cities that we did not take from them—the whole region of Argob, Og's kingdom in Bashan ... destroying every city, men, women and children ... But all the livestock and the plunder from their cities we carried off for ourselves."

Og's destruction is told in Psalms 135:11 and 136:20 as one of many great victories for the nation of Israel, and the Book of Amos 2:9 may refer to Og as "the Amorite" whose height was like the height of the cedars and whose strength was like that of the oaks.

Og and the Rephaim

In Deut. 3:11 and later in the book of Numbers and Joshua, Og is called the last of the Rephaim. Rephaim is a Hebrew word for giants. Deut. 3:11 declares that his "bedstead" (translated in some texts as "sarcophagus") of iron is "nine cubits in length and four cubits in width", which is 13.5 ft by 6 ft according to the standard cubit of a man. It goes on to say that at the royal city of Rabbah of the Ammonites, his giant bedstead could still be seen as a novelty at the time the narrative was written. If the giant king's bedstead was built in proportion to his size as most beds are, he may have been between 9 and 13 feet in height. However, later Rabbinic tradition has it, that the length of his bedstead was measured with the cubits of Og himself. The Talmud further embellishes in fantastic detail that Og was so large that he sought the destruction of the Israelites by uprooting a mountain so large, that it would have crushed the entire Israelite encampment. The Lord caused a swarm of ants to dig away the center of the mountain, which was resting on Og's head. The mountain then fell onto Og's shoulders. As Og attempted to lift the mountain off himself, the Lord caused Og's teeth to lengthen outward, becoming embedded into the mountain that was now surrounding his head. Moses, fulfilling the LORD's injunction not to fear him, seized a stick of ten cubits length, and jumped a similar vertical distance, succeeding in striking Og in the ankle. Og fell down and died upon hitting the ground.[2] It is noteworthy that the region north of the river Jabbok, or Bashan, "the land of Rephaim", contains hundreds of megalithic stone tombs (dolmen) dating from the 5th to 3rd millennia BC. In 1918, Gustav Dalman discovered in the neighborhood of Amman Jordan (Amman is built on the ancient city of Rabbah of Ammon) a noteworthy dolmen which matched the approximate dimensions of Og's bed as described in the Bible. Such ancient rock burials are seldom seen west of the Jordan river, and the only other concentration of these megaliths are to be found in the hills of Judah in the vicinity of Hebron, where the giant sons of Anak were said to have lived (Numbers 13:33).[3]

Og in non-Biblical inscriptions

A reference to "Og" appears in a Phoenician inscription from Byblos (Byblos 13) published in 1974 by Wolfgang Rölling in "Eine neue phoenizische Inschrift aus Byblos," (Neue Ephemeris für Semitische Epigraphik, vol 2, 1-15 and plate 1). It appears in a damaged 7-line funerary inscription that Rölling dates to around 500 BC, and appears to say that if someone disturbs the bones of the occupant, "the mighty Og will avenge me."

A possible connection to Og and the Rephaim kings of Bashan can also be made with the much older Canaanite Ugaritic text KTU 1.108 from the 13th century B.C., which uses the term "king" in association with the root /rp/ or "Rapah" (the Rephaim of the Bible) and geographic place names that probably correspond to the cities of Ashtaroth and Edrei in the Bible, and with which king Og is expressly said to have ruled from (Deuteronomy 1:4; Joshua 9:10; 12:4; 13:12, 31). The clay tablet from Ugarit KTU 1.108[4] reads in whole, "May Rapiu, King of Eternity, drink [w]ine, yea, may he drink, the powerful and noble [god], the god enthroned in Ashtarat, the god who rules in Edrei, whom men hymn and honour with music on the lyre and the flute, on drum and cymbals, with castanets of ivory, among the goodly companions of Kothar. And may Anat the power<ful> drink, the mistress of kingship, the mistress of dominion, the mistress of the high heavens, [the mistre]ss of the earth."

Og also had Midianite links. Jethro of the Bible also appears to have Midianite connections. The "Great Kahns" of central Asia may also have historical links to the family. Some Hebrew origins are connected to Og among the shepherd bands.

"Ogias the Giant"

The 2nd century BC apocryphal book "Ogias the Giant" or "The Book of Giants" depicts the adventures of a giant named Ogias who fought a great dragon, and who was supposedly either identical with the Biblical Og or was Og's father.

The book enjoyed considerable currency for several centuries, especially due to having been taken up by the Manichaean religion.

Hurtaly

In "Pantagruel", Rabelais lists Hurtaly (a version of Og) as one of Pantagruel's ancestors. He describes Hurtaly as sitting astride the Ark, saving it from shipwreck by guiding it with his feet as the grateful Noah and his family feed him through the chimney.

See also

References

- ↑ From Og's Circle to the Wise Observatory, Yuval Ne'eman, Tel Aviv University

- ↑ Talmud Bavli: Berachot 54b

- ↑ Werner Keller Bible As a History 1995, p. 153 ISBN 1566198011, ISBN 9781566198011

- ↑ Wyatt, N. (2002). Religious texts from Ugarit - 2nd Edition. Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 395–396. ISBN 0-8264-6048-8.

Further reading

- Kosman, Admiel: "The Story of a Giant Story – The Winding Way of Og King of Bashan in the Jewish Aggadic Tradition", in: HUCA 73, (2002) pp. 157–90.