o-Toluidine

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Methylaniline | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

| 95-53-4 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:66892 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1381 |

| ChemSpider | 13854136 |

| KEGG | C14403 |

| PubChem | 17395403 |

| UNII | B635MZ0ZLU |

| Properties | |

| C7H9N | |

| Molar mass | 107.16 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless to pale-yellow liquid |

| Odor | Aromatic, aniline-like odor |

| Density | 0.97759 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −23.7 °C (−10.7 °F; 249.5 K) |

| Boiling point | 200 to 202 °C (392 to 396 °F; 473 to 475 K) |

| 0.19 g/100 ml at 20 °C | |

| Vapor pressure | 0.307531 mmHg (25 °C) |

| Hazards | |

| EU classification (DSD) |

|

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 85 °C (185 °F; 358 K) |

| 481.67 °C (899.01 °F; 754.82 K) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

900 mg/kg (rat, oral) 3235 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Toluidine |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

o-Toluidine (ortho-toluidine) is an organic compound with the chemical formula C7H9N. This arylamine is a colorless to pale-yellow liquid with a poor solubility in water.

Biotransformation

Absorption distribution and excretion

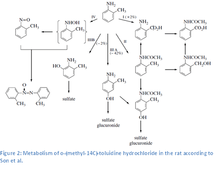

Through biological monitoring it was discovered that o-toluidine may be absorbed through inhalation and dermal contact. Extensive absorption (at least 92% of the administered oral dose) of o-toluidine from the gastrointestinal tract was observed.[2] Studies show that the absorption of o-toluidine from the gastrointestinal tract in rats is rapid with peak values at 1 hour; the blood values were near zero in 24 hours.[3] It is expected of aromatic amines, like o-toluidine, to be absorbable through the skin due to their lipid solubility. 48 hours following subcutaneous injection of labeled o-toluidine hydrochloride into fats,[4] detected radioactivity in decreasing range: liver > kidney > spleen, colon > lung, bladder. In another study, 72 hours after oral application to rats, radioactivity was detected in decreasing range: blood > spleen > kidney > liver > subcutaneous abdominal fat > lung > heart > abdominal skin > bladder > gastrointestinal tract > bone marrow > brain > muscle > testes.[5] The main excretion pathway is through the urine where up to one-third of the administered compound was recovered unchanged. Major metabolites were determined to be 4-amino-m-cresol and to a lesser extent, N-acetyl-4-amino-m-cresol,[4] azoxytoluene, o-nitrosotoluene, N-acetyl-o-toluidine, N-acetyl-o-aminobenzyl alcohol, anthranilic acid, N-acetyl-anthranilic acid, 2-amino-m-cresol, p-hydroxy-o-toluidine and other unidentified substances. Conjugates that were formed were predominated by sulfate conjugates over glucuronide conjugates by a ratio of 6:1.

Metabolism

The results from metabolism studies in rats show that, like other monocyclic aromatic amines, the metabolism of o-toluidine involves many competing activating and deactivating pathways, including N-acetylation, N-oxidation and N-hydroxylation, and ring oxidation.[6] 4-Hydroxylation and N-acetylation of toluidine are the major metabolic pathways in rats. The primary metabolism of o-toluidine takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum. Exposure to o-toluidine enhances the microsomal activity of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase (particularly in the kidney), NAPDH-cytochrome c reductase and the content of cytochrome P-450. Cytochrome P450–mediated N-hydroxylation to N-hydroxy-o-toluidine, a carcinogenic metabolite, occurs in the liver. N-Hydroxy-o-toluidine can be either metabolized to o-nitrosotoluene or conjugated with glucuronic acid or sulfate and transported to the urinary bladder via the blood. Once in the bladder, N-hydroxy-o-toluidine can be released from the conjugates in an acidic urine environment to either react directly with DNA or be bio-activated via sulfation or acetylation by cytosolic sulfotransferases or N-acetyltransferases (presumably NAT1).[7] The postulated activated form (based on comparison with other aromatic amines), N-acetoxy-o-toluidine, is a reactive ester that forms electrophilic arylnitrenium ions that can bind to DNA.[6][8][9] Other activation pathways (ring-oxidation pathways) for aromatic amines include peroxidase-catalyzed reactions that form reactive metabolites (quinone-imines formed from nonconjugated phenolic metabolites) in the bladder. These metabolites can produce reactive oxygen species, resulting in oxidative cellular damage and compensatory cell proliferation. Support for this mechanism comes from studies of oxidative DNA damage induced by o-toluidine metabolites in cultured human cells (HL-60), calf thymus DNA, and DNA fragments from key genes thought to be involved in carcinogenesis (the c-Ha-ras oncogene and the p53 tumor-suppressor gene).[10][11] Also supporting this mechanism are observations of o-toluidine-induced DNA damage (strand breaks) in cultured human bladder cells and bladder cells from rats and mice exposed in vivo to o-toluidine.[12][13]

Binding of hemoglobin

Binding of o-toluidine metabolites to hemoglobin has also been observed in rats.[14] Hemoglobin adducts are thought to be formed from the o-toluidine metabolite o-nitrosotoluene,[9][15] which also causes urinary-bladder cancer in rats.[16] Studies of other aromatic amines that cause bladder cancer have shown that during transport of the N-hydroxyarylamines to the bladder, bioreactive metabolites (nitroso compounds) can form and bind to hemoglobin in the blood.[17] The metabolites hereby oxidize the hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which cannot bind oxygen. Methemoglobinemia (higher presence of methemoglobin, the inactive ferric form of red blood cell heme) results in decreased supply of oxygen to peripheral tissues.[18][19] Evidence suggesting that this pathway is relevant to humans comes from numerous studies that detected o-toluidine hemoglobin adducts in humans (following both occupational and non-occupational exposures), consistent with observations in experimental animals.[6]

Carcinogenicity

Although the mechanisms of carcinogenicity of o-toluidine are not completely understood, the available evidence suggests that they are complex and involve several key modes of action, including metabolic activation that results in binding of reactive metabolites to DNA and proteins, mutagenicity, oxidative DNA damage, chromosomal damage, and cytotoxicity.[10][11]

History

o-Toluidine was first listed in the Third Annual Report on Carcinogens as ‘reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen’ in 1983, based on sufficient evidence from studies in experimental animals. The Report on Carcinogens (RoC) is a U.S. congressionally-mandated, science-based public health report that identifies agents, substances, mixtures, or exposures in the environment that pose a hazard to people residing in the United States[20] Since then, other cancer related studies have been published and the listing of o-toluidine was changed to ‘known to be a human carcinogen’. o-toluidine was especially linked to bladder cancer. This was done 31 years later in the Thirteenth Report on Carcinogens (2014).[7] The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified o-toluidine as ‘carcinogenic to humans (group 1)’.[21]

Cancer studies in humans

The relationship established between exposure to o-toluidine and bladder cancer in humans was based on the evaluation of cohort studies of dye workers and rubber-chemical workers, and a population-based case-control study. The cohort study on rubber-chemical workers in the U.S. was the most informative, because it provided the best assessment of o-toluidine exposure and coexposure. However, an increased risk of bladder cancer was observed in all the named studies with adequate latency (time since exposure) that used statistical or other methods capable of detecting or proving a (likely) association. The risk of bladder cancer increased with increasing level of duration of exposure to o-toluidine and time since the first exposure; this supported a causal relationship.

The findings increased bladder cancer risk in different cohorts with different exposure conditions and different coexposures strongly supported the conclusion that o-toluidine was the common causal risk factor.

Cancer studies in animals

Studies using experimental animals were performed. The statistically significant increase of incidences of malignant tumors or benign and malignant tumors combined at several different tissue sites in rat and mice was related to exposure to o-toluidine. Dietary exposure (NTP 1996) to the compound caused tumors in the urinary bladder and other connective tissue in rats of both sexes. The most important outcome of these studies was that rats developed tumors at the same tissue sites as observed in humans. The observation of tumors at tissue sites in addition to the urinary bladder supported the conclusion that o-toluidine was a carcinogen.

Synthesis

o-Toluidine can be synthesized from toluene. The direct aromatic amination is very effective when done with a parent nitrenium ion, but o-toluidine can also be synthesized in other ways. For example, by the amination of toluene with methylhydroxylamine or hydroxylammonium salts in presence of aluminum trichloride.[22] The reaction using a nitrenium ion is not regionselective and multiple structural isomers will be present in the product. Figure 2 shows a very general synthesis reaction of o-toluidine and the other products (p-toluidine and m-toluidine). To obtain pure o-toluidine, the isomers need to be separated.

Toxicology

The main excretion-pathway is revealed to be through urine where up to one-third of the administered compound was recovered unchanged. o-toluidine and metabolites are known to bind to hemoglobin. The o-toluidine metabolite o-nitrosotoluene, is proven to cause bladder cancer in rats and is thought to bind to hemoglobin in humans. o-Toluidine exposure has been researched in a number of different degrees in animals.[3][7][23][24]

Single exposure

o-Toluidine was found to be harmful to rats following acute oral exposure with LD50 of 900 and 940 mg/kg bodyweight. The compound was also found to be of low toxicity in rabbits following acute dermal exposure with an LD50 of 3235 mg/kg bodyweight. Toxicity following inhalation was not identified. Symptoms following acute exposure include cyanosis (blue or purple coloration of the skin due to low oxygen saturation in the tissue), increased methemoglobin levels and moderate skin irritation and severe eye irritation in rabbits.

Short-term exposure

Only oral short-term exposure in rats was researched of o-toluidine. Dermal exposure affected the ovarian cycle, ovary morphostructure, the ability to reproduce and the progeny in female rats when administered for four months (Malysheva and Zaitseva, 1982). Male rats treated similarly showed stimulated spermatogenesis (production of sperm cells) (Malysheva et al., 1983). Inhalation exposure was not identified. Rats were administered with the compound with a dose of 1125 mg/kg bodyweight over five days (225 mg/kg bodyweight per day). Observed symptoms included increased methemoglobin levels, congestion, hemosiderosis (iron overload disorder), hematopoiesis (formation of blood cellular components) in the spleen and a 1.5 to 3.0 times increase in spleen weight.

Chronic exposure

Chronic oral exposure to o-toluidine hydrochloride has induced increased incidences of tumors (benign and malignant) in rats and mice. In one study, rats were given doses of approximately 150 and 300 mg/kg bodyweight (low dose and high dose), a control-group was also present (NCI, 1979; Goodman et al., 1984). The exposure was associated with dose-related decrease in bodyweight gain, decrease in survival and with increased incidences of numerous types of cancer (sarcomas, angiosarcomas, fibrosarcomas, osteosarcomas, fibromas, fibroadenomas and mesothelioma). Non-neoplastic effects were also observed. These included hyperplasia (abnormal increase in volume of tissue), fibrosis (formation of excess fibrous connective tissue) and liver necrosis (premature death of cells in living tissue). Multiple other studies where rats or mice were given o-toluidine over a prolonged period of time had similar results, including but not limited to a decrease in survivability and increased incidences of different types of cancer (Hecht et al., 1982; Weisburger et al., 1978; NCI, 1979; Weisburger et al., 1978).

Human exposure

Acute human exposure to o-toluidine can cause painful hematuria (presence of red blood cells in the urine) (Goldbarb and Finelli, 1974). Chronic exposure to o-toluidine in humans was also observed in multiple retrospective cohort studies in the dyestuff industry. The results include increased death incidences and increased incidences of bladder cancer. It proved difficult however to definitively link these to o-toluidine in due to the exposure to other expected carcinogenic compounds in the dyestuff industry. One study assessed the increased incidences of mortality and bladder cancer in 906 employers of a dyestuff factory in northern Italy over a mean latent period of 25 years. Mortality from bladder cancer was significantly higher in the employers than the people only exposed to the particular chemicals present in the factory, in use or intermittent contact. o-Toluidine was concluded to be almost certainly capable of causing bladder cancer in men.

Another study recorder expected and observed cases of bladder cancer at a rubber factory in upstate New York (Ward et al., 1991). The study assessed 1,749 male and female employers over a period of 15 years. Exposure was primarily to o-toluidine and aniline and a significant increase in incidences of bladder cancer was observed. However, the carcinogenicity could not be attributed to o-toluidine definitively. Other studies include Vigliani & Barsotti (1961), Khlebnikova et al. (1970), Zavon et al. (1973), Conso & Pontal (1982), and Rubino et al. (1982).

The specific mechanisms of carcinogenicity of o-toluidine are not completely understood, but they are known to be complex and to involve metabolic activation, which results in formation of reactive metabolites. The earlier mentioned o-nitrosotoluene, which causes cancer in rats, is an example of these reactive metabolites. Research has indicated that o-toluidine is a mutagen and causes oxidative DNA damage and chromosomal damage (Skipper et al. 2010). Multiple studies have shown that the compound induces oxidative DNA damage and strand breaks in cultured human cells (Watanabe et al. 2010; Ohkuma et al. 1999, Watanabe et al. 2010). DNA damage was also observed in rats and mice exposed in vivo to o-toluidine (Robbiano et al. 2002, Sekihashi et al. 2002) and even large scale chromosomal damage was observed in yeast and mammalian cells exposed to o-toluidine in vitro. More generally, chromosomal instability is known to be induced by aromatic amines in urinary bladder cells. Chromosomal instability may lead to both aneuploidy (presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell), which is observed in cancer cells, and loss of heterozygosity (loss of the entire gene and the surrounding chromosomal region), which can result in the absence of a tumor suppressor gene (Höglund et al. 2001, Sandberg 2002, Phillips and Richardson 2006).

Applications

o-Toluidine is used or applied in different circumstances. It is used the most for dye, especially for coloring hair. The other usages of o-toluidine are specific determination of glucose in blood and the most recent one, the separation of toxic metal ions, which is still in the research phase.

Dye

o-Toluidine has been used as a dye precursor since the 19th century, when synthetic dye was produced.[25] In the years that followed, the aromatic amine functioned as a precursor of many dyes and pigments for consumer goods. But when the carcinogenicity of o-toluidine for animals was recognized, and that it potentiality could be carcinogenic for humans, the production of o-toluidine and its use in dye manufacturing has been largely banned in the Western world and in many parts of the East. But there are still a few dyes that are based on this compound. The most known compounds are petroleum products and yellow organic pigments. It is also an essential compound in the production of 4-chloro-o-toluidine and 4-amino-2′,3-dimethylazobenzene, which are also dyes.

Specific determination of glucose

o-Toluidine can also be used for measuring serum glucose concentration, in the form of acetic acid–o-toluidine.[26] The o-toluidine reaction for the estimation of glucose concentration in the serum gained massive popularity in the 1970s. This method was mostly used by clinical laboratories. Because of the potential health hazard, the laboratories now have a modified method by using alternative compounds.

Separation of toxic metal ions

The increasing level of heavy metals in the environment is a serious environmental problem. Various methods have been developed to remove these metals from aqueous systems, but these methods have limitations. Because of the limitations, researchers prompted to exploit inorganic materials as ion exchangers. These inorganic ion exchangers are able to obtain specific metal ions/anions or organic molecules. Following research in 2010,[27] there has been a synthesis and analytical application on a new thermally stable composite cation exchange material: poly-o-toluidine stannic molybdate. This material showed a high selectivity for Pb2+ and Hg2+ metal ions.

Isomers

o-Toluidine has two more configurations, p-toluidine and m-toluidine. While most properties of these toluidine are comparable to o-toluidine, there are some differences.

p-toluidine

The molecular weight and molecular formula are the same as o-toluidine. It has a boiling point of 200.4 °C and a melting point of 43.6 °C. It has an aromatic, wine-like odor.

Absorption of toxic quantities by any route causes cyanosis (blue discoloration of lips, nails, skin), nausea and vomiting, and coma may follow. Repeated inhalation of low concentrations may cause pallor, low-grade secondary anemia, fatigue, and loss of appetite. Contact with eyes causes irritation.

It is a confirmed animal carcinogen with unknown relevance to humans. The substance can be absorbed into the body by inhalation, through the skin and by ingestion. The symptoms are irritated eyes and skin, dermatitis, hematuria, methemoglobinemia, cyanosis, nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure, convulsions, anemia, and fatigue.

m-toluidine

Absorption of toxic quantities by any route causes cyanosis (blue discoloration of lips, nails, skin), nausea and vomiting, and coma may follow. Repeated inhalation of low concentrations may cause pallor, low-grade secondary anemia, fatigue, and loss of appetite. Contact with eyes causes irritation.

It is not classifiable as a human carcinogen. The substance can be absorbed into the body by inhalation, through the skin and by ingestion. The symptoms are irritated eyes and skin, dermatitis, hematuria, methemoglobinemia, cyanosis, nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure, convulsions, anemia, and fatigue.

References

- ↑ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 669. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

The names ‘toluidine’, ‘anisidine’, and ‘phenetidine’ for which o-, m-, and p- have been used to distinguish isomers, and ‘xylidine’ for which numerical locants, such as 2,3-, have been used, are no longer recommended, nor are the corresponding prefixes ‘toluidine’, ‘anisidino’, ‘phenetidine’, and ‘xylidino’.

- ↑ Cheever, K.; Richards, D.; Plotnick, H. (1980). "Metabolism of o-, m- and p-toluidine in the adult male rat". Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 56: 361–369. doi:10.1016/0041-008x(80)90069-1.

- 1 2 Hiles, R. C.; Abdo, K. M. (1990). "5. ortho-Toluidine". In Buhler, D. R.; Reed, D. J. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Solvents (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 202–207.

- 1 2 Son, O. S.; Everett, D. W.; Fiala, E. S. (1980). "Metabolism of o-[methyl-14C]toluidine in the F344 rat". Xenobiotica. 10: 457–468. doi:10.3109/00498258009033781.

- ↑ Brock, W. J.; Hundley, S. G.; Lieder, P. H. (1990). "Hepatic macromolecular binding and tissue distribution of ortho- and para-toluidine in rats". Toxicol. Lett. 54: 317–325. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(90)90199-v.

- 1 2 3 Riedel, K.; Scherer, G.; Engl, J.; Hagedorn, H. W.; Tricker, A. R. (2006). "Determination of three carcinogenic aromatic amines in urine of smokers and nonsmokers". J. Anal. Toxicol. 30 (3): 187–195. doi:10.1093/jat/30.3.187.

- 1 2 3 "o-Toluidine" (PDF). Report on Carcinogens (13th ed.). US National Institute of Health.

- ↑ Kadlubar, F. F.; Badawi, A. F. (1995). "Genetic susceptibility and carcinogen-DNA adduct formation in human urinary bladder carcinogenesis". Toxicol. Lett. 82–83: 627–632. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(95)03507-9.

- 1 2 English, J. C.; Bhat, V. S.; Ball, G. L.; C. J., McLellan (2012). "Establishing a total allowable concentration of o-toluidine in drinking water incorporating early lifestage exposure and susceptibility". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 64 (2): 269–284. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.08.011.

- 1 2 Ohkuma, Y. Y.; Hiraku, S.; Oikawa, S.; Yamashita, N.; Murata, M.; Kawanishi, S. (1999). "Distinct mechanisms of oxidative DNA damage by two metabolites of carcinogenic o-toluidine". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 372 (1): 97–106. doi:10.1006/abbi.1999.1461.

- 1 2 Watanabe, C; Egami, T; Midorikawa, K.; Hiraku, Y.; Oikawa, S.; Kawanishi, S; Murata, M. (2010). "DNA damage and estrogenic activity induced by the environmental pollutant 2-nitrotoluene and its metabolite". Environ. Health. Prev. Med. 15 (5): 319–326. doi:10.1007/s12199-010-0146-1.

- ↑ Robbiano, L.; Carrozzino, R.; Bacigalupo, M.; Corbu, C.; Brambilla, G. (2002). "Correlation between induction of DNA fragmentation in urinary bladder cells from rats and humans and tissue-specific carcinogenic activity". Toxicology. 179 (1–2): 115–128. doi:10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00354-2.

- ↑ Sekihashi, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Matsumura, Y.; Ueno, S.; Watanabe-Akanuma, M.; Kassie, F; Knasmuller, S.; Tsuda, S.; Sasaki, Y. F. (2002). "Comparative investigation of multiple organs of mice and rats in the comet assay". Mutat. Res. 517 (1–2): 53–75. doi:10.1016/s1383-5718(02)00034-7.

- ↑ Birnier, G.; Neumann, H. (1988). "Biomonitoring of aromatic amines. II: Haemoglobin binding of some monocyclic aromatic amines". Arch. Toxicol. 62 (2–3): 110–115.

- ↑ Eyer, P. (1983). "The red cell as a sensitive target for activated toxic arylamines". Arch. Toxicol. Suppl. 6: 3–12.

- ↑ Hecht, S. S.; El-Bayoumy, K.; Rivenson, A.; Fiala, E. (1983). "Bioassay for carcinogenicity of 1,2-dimethyl-4-nitrosobiphenyl, o-nitrosotoluene, nitrosobenzene and the corresponding amines in Syrian golden hamsters". Cancer Lett. 20: 349–354. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(83)90034-4.

- ↑ Skipper, P. L.; Tannenbaum, S. R. (1994). "Molecular dosimetry of aromatic amines in human populations". Environ. Health Perspect. 102 (suppl. 6): 17–21.

- ↑ Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB, online database). National Toxicology Information Program. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1997.

- ↑ Clayton, G. D.; Clayton, F. E., eds. (1981). Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 2A (3rd rev. ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Burwell, S. M. (2014). Report on Carcinogens (13th ed.).

- ↑ "IARC Monographs". monographs.iarc.fr. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ↑ The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (11th ed.), Merck, 1989, ISBN 091191028X

- ↑ Gregg, N.; et al. (1998). o-Toluidine. World Health Organization. pp. 5–22. ISBN 92-4-153007-3. (NLM classification: QV 235.)

- ↑ Rubino, G. F.; Scansetti, G.; Piolatto, G.; Fira, E. (1982). "The carcinogenic effect of aromatic amines: An epidemiological study on the role of o-toluidine and 4,4′-methylenebis(2-methylaniline) in inducing bladder cancer in man". Env. Res. 27 (2): 241–254. doi:10.1016/0013-9351(82)90079-2.

- ↑ Freeman, H. S. (November 2012), Use of o-toluidine in the manufacture of dyes and on the potential for exposure to other chemicals in the processes involving o-toluidine, North Carolina State University, p. 15

- ↑ Rej, R. (1973). "A study of the direct o-toluidine blood glucose determination". Clin. Chim. Acta. 43 (1): 105–11. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(73)90125-3.

- ↑ Nabi, S. A.; et al. (2010). "Synthesis, characterization and analytical applications of a new composite cation exchange material poly-o-toluidine stannic molybdate for the separation of toxic metal ions". Chem. Eng. J. 165: 529–530. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2010.09.064.