O-Desmethyltramadol

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Converted Metabolite |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6[1] |

| Biological half-life | ~ 9 h |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

80456-81-1 |

| PubChem (CID) | 130829 |

| ChemSpider |

115703 |

| UNII |

2WA8F50C3F |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1400 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H23NO2 |

| Molar mass | 249.349 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

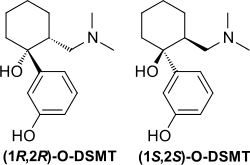

O-Desmethyltramadol (O-DSMT) is an opioid analgesic and the main active metabolite of tramadol.[2] (+)-O-DSMT[lower-alpha 1] is the most important metabolite of tramadol produced in the liver after tramadol is consumed. Tramadol is demethylated by the liver enzyme CYP2D6[3] in the same way as codeine, and so similarly to the variation in effects seen with codeine, individuals who have a less active form of CYP2D6 ("poor metabolisers") will tend to get reduced analgesic effects from tramadol. This also results in a ceiling effect (dependent on CYP2D6 availability) which limits tramadol's range of therapeutic benefits to the treatment of moderate pain.

Pharmacology

O-DSMT is considerably more potent as a μ opioid agonist compared to tramadol.[4] Additionally, unlike tramadol, it is a high-affinity ligand of the δ- and κ-opioid receptors.[5]

The two enantiomers of O-DSMT show quite distinct pharmacological profiles;[6] both (+) and (−)-O-DSMT are inactive as serotonin reuptake inhibitors,[7] but (−)-O-DSMT retains activity as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor,[8] and so the mix of both the parent compound and metabolites contributes significantly to the complex pharmacological profile of tramadol. While the multiple receptor targets can be beneficial in the treatment of pain (especially complex pain syndromes such as neuropathic pain), it increases the potential for drug interactions compared to other opioids, and may also contribute to side effects.

Recreational use

O-DSMT has recently been marketed as a currently legal substitute for illegal opioid drugs, either in powder form or mixed into various other preparations. One such blend sold under the brand Krypton and containing powdered kratom leaf (Mitragyna speciosa) laced with O-DSMT was reportedly linked to at least 9 accidental deaths from overdose during 2010–2011.[9][10][11]

The metabolic conversion of tramadol to O-DSMT is highly dependent on individual metabolism, meaning that two users with an identical opioid tolerance can experience vastly different effects from the same dose. For this reason, tramadol is always initiated at the lowest possible dose in clinical settings and then titrated to the lowest effective dose. Recreational users tend to start with much higher doses without taking this into account, greatly increasing the risk of overdose.

Role in drug development

The opioid medication tapentadol was developed to mimic the actions of O-DSMT in order to create a weak-moderate analgesic which is not dependent on metabolic activation. Tapentadol, however, is generally considered to be a stronger analgesic than tramadol. This may be illusory due to the metabolism-dependent effects of tramadol.

Metabolites

O-DSMT is metabolized in the liver into the active metabolite N,O-didesmethyltramadol via CYP3A4 & CYP2B6. The inactive tramadol metabolite N-desmethyltramadol is metabolized into the active metabolite N,O-didesmethyltramadol by CYP2D6.

See also

Note list

- ↑ N.B. that the "O" is capitalized and italicized and refers to the oxygen atom in this instance. A small case letter "o" that is likewise italicized and a prefix, in chemistry, usually indicates a substitution in the "ortho" or second position placeholder of the benzene; which would be the next place free of a heteroatom (non-hydrogen) after the juncture taken by the phenyl connector on the benzene.

References

- ↑ Tramadol Pharmacokinetics, PharmGKB

- ↑ Sevcik, J; Nieber, K; Driessen, B; Illes, P (1993). "Effects of the central analgesic tramadol and its main metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, on rat locus coeruleus neurones". British Journal of Pharmacology. 110 (1): 169–76. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13788.x. PMC 2175982

. PMID 8220877.

. PMID 8220877. - ↑ Borlak, J; Hermann, R; Erb, K; Thum, T (2003). "A rapid and simple CYP2D6 genotyping assay--case study with the analgetic tramadol". Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 52 (11): 1439–43. doi:10.1016/S0026-0495(03)00256-7. PMID 14624403.

- ↑ Dayer, P; Desmeules, J; Collart, L (1997). "Pharmacology of tramadol". Drugs. 53 Suppl 2: 18–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-199700532-00006. PMID 9190321.

- ↑ Potschka H, Friderichs E, Löscher W (September 2000). "Anticonvulsant and proconvulsant effects of tramadol, its enantiomers and its M1 metabolite in the rat kindling model of epilepsy". Br. J. Pharmacol. 131 (2): 203–12. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703562. PMC 1572317

. PMID 10991912.

. PMID 10991912. - ↑ Garrido, MJ; Valle, M; Campanero, MA; Calvo, R; Trocóniz, IF (2000). "Modeling of the in vivo antinociceptive interaction between an opioid agonist, (+)-O-desmethyltramadol, and a monoamine reuptake inhibitor, (-)-O-desmethyltramadol, in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 295 (1): 352–9. PMID 10992001.

- ↑ Bamigbade, T. A.; Davidson, C.; Langford, R. M.; Stamford, J. A. (1997). "Actions of tramadol, its enantiomers and principal metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, on serotonin (5-HT) efflux and uptake in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus". British journal of anaesthesia. 79 (3): 352–356. doi:10.1093/bja/79.3.352. PMID 9389855.

- ↑ Driessen, B; Reimann, W; Giertz, H (1993). "Effects of the central analgesic tramadol on the uptake and release of noradrenaline and dopamine in vitro". British Journal of Pharmacology. 108 (3): 806–11. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12882.x. PMC 1908052

. PMID 8467366.

. PMID 8467366. - ↑ Arndt, T; Claussen, U; Güssregen, B; Schröfel, S; Stürzer, B; Werle, A; Wolf, G (2011). "Kratom alkaloids and O-desmethyltramadol in urine of a "Krypton" herbal mixture consumer". Forensic Science International. 208 (1–3): 47–52. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.10.025. PMID 21112167.

- ↑ Bäckstrom, BG; Classon, G; Löwenhielm, P; Thelander, G (2010). "Krypton--new, deadly Internet drug. Since October 2009 have nine young persons died in Sweden". Lakartidningen. 107 (50): 3196–7. PMID 21294331.

- ↑ Kronstrand, R; Roman, M; Thelander, G; Eriksson, A (2011). "Unintentional fatal intoxications with mitragynine and O-desmethyltramadol from the herbal blend Krypton". Journal of analytical toxicology. 35 (4): 242–7. doi:10.1093/anatox/35.4.242. PMID 21513619.