Nusaybin

| Nusaybin ܢܨܝ̣ܒ݂ܝ̣ܢ ܢܨܝܝ̣ܒ݂ܝ̣ܢ Nṣībīn | |

|---|---|

| |

Nusaybin ܢܨܝ̣ܒ݂ܝ̣ܢ | |

| Coordinates: 37°04′31.2″N 41°12′56.5″E / 37.075333°N 41.215694°ECoordinates: 37°04′31.2″N 41°12′56.5″E / 37.075333°N 41.215694°E | |

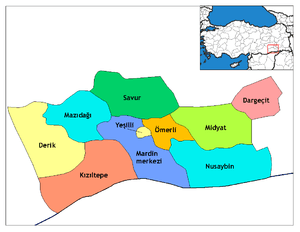

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Mardin |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ergün Baysal (State-appointed caretaker[1]) |

| • Kaymakam | Ergün Baysal |

| Area[2] | |

| • District | 1,169.15 km2 (451.41 sq mi) |

| Elevation[3] | 471 m (1,545 ft) |

| Population (2012)[4] | |

| • Urban | 88,047 |

| • District | 115,072 |

| • District density | 98/km2 (250/sq mi) |

| Post code | 47300 |

| Website |

www |

Nusaybin (pronounced [nuˈsajbin]; Akkadian: Naṣibina;[5] Classical Greek: Νίσιβις, Nisibis; Arabic: نصيبين, Syriac: ܢܨܝܒܝܢ, Nṣībīn; Armenian: Մծբին, Mtsbin; Kurdish: Nisêbîn) is a city and multiple titular see in Mardin Province, Turkey. The population of the city is 83,832[6] as of 2009. The population is of ethnic Kurdish, Assyrian and Arab descent.

With a history going back nearly 3,000 years, Nusaybin was ruled and settled by various groups. First mentioned as an Aramean settlement Naşibīna in 901 BCE and was captured by Assyria in 896 BCE, in the 4th and 5th centuries CE it was one of the great centers of Syriac scholarship, along with nearby Edessa.[7]

History

Ancient Period

First mentioned in 901 BCE, Naşibīna was an Aramaean kingdom captured by the Assyrian king Adad-Nirari II in 896.[8] By 852 BCE, Naṣibina had been fully annexed to the Neo-Assyrian Empire and appeared in the Assyrian Eponym List as the seat of an Assyrian provincial governor named Shamash-Abua.[9] It remained part of the Assyrian Empire until its collapse in 608 BCE.

It was under Babylonian control until 536 BCE, when it fell to the Achamaenid Persians, and remained so until taken by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. The Seleucids refounded the city as Antiochia Mygdonia (Greek: Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Μυγδονίας), mentioned for the first time in Polybius' description of the march of Antiochus III the Great against Molon (Polybius, V, 51). Greek historian Plutarch suggested that the city was populated by Spartan descendants. Around the 1st century CE, Nisibis (נציבין, Netzivin) was the home of Judah ben Bethera, who founded a famous yeshiva there.[10]

Classical Period

Like many other cities in the marches where Roman and Parthian powers confronted one another, Nisibis was often taken and retaken: it was captured by Lucullus after a long siege from the brother of Tigranes (Dio Cassius, XXXVI, 6-7); and captured again by Trajan in 115 AD, for which he gained the name of Parthicus (ibid., LXVIII, 23), then lost and regained against the Jews during the Kitos War. Lost in 194, it was again conquered by Septimius Severus, who made it his headquarters and re-established a colony there (ibid., LXXV, 23). The last battle between Rome and Parthia was fought in the vicinity of the city in 217.[11] With the fresh energy of the new Sassanid dynasty, Shapur I conquered Nisibis, was driven out, and returned in the 260s. In 298, by a treaty with Narseh, the province of Nisibis was acquired by the Roman Empire.

Nisibis (Syriac: ܢܨܝܒܝܢ, Nṣibin, later Syriac ܨܘܒܐ, Ṣōbā) had an Assyrian Christian bishop from 300, founded by Babu (died 309). War was begun again by Shapur II in 337, who besieged the city in 338, 346 and 350, when Jacob (James) of Nisibis, Babu's successor, was its bishop. Nisibis was the home of Ephrem the Syrian, who remained until its surrender to the Persians by Roman Emperor Jovian in 363.

The Roman historian of the 4th century, Ammianus Marcellinus, gained his first practical experience of warfare as a young man at Nisibis under the master of the cavalry, Ursicinus. From 360 to 363, Nisibis was the camp of Legio I Parthica. Because of its strategic importance on the Persian border Nisibis was heavily fortified. Ammianus lovingly calls Nisibis the "impregnable city" (urbs inexpugnabilis) and "bulwark of the provinces" (murus provinciarum).

In 363 Nisibis was ceded back to the Persians after the defeat of Emperor Julian. Before that time the population of the town was forced by the Roman authorities to leave Nisibis and move to Amida. Emperor Jovian allowed them only three days for the evacuation. Historian Ammianus Marcellinus was again an eyewitness and condemns Emperor Jovian for giving up the fortified town without a fight. Marcellinus' point-of-view is certainly in line with contemporary Roman public opinion.

Later, the bishop of Nisibis was the Metropolitan Archbishop of the Ecclesiastical province of Bit-Arbaye. In 410 it had six suffragan sees and as early as the middle of the 5th century was the most important episcopal see of the Church of the East after Seleucia-Ctesiphon, and many of its Nestorian, Assyrian Church of the East or Jacobite bishops were renowned for their writings: Barsumas, Osee, Narses, Jesusyab and Ebed-Jesus.

According to Al-Tabari some 12,000 Persians of good lineage from Istakhr, Isfahan and other regions settled at Nisibis in the 4th century, and their descendents were still there at the beginning of the 7th century.[12]

The first theological, philosophical and medical School of Nisibis, founded at the introduction of Christianity into the city by ethnic Assyrians of the Assyrian Church of the East,[13] was closed when the province was ceded to the Persians. Ephrem the Syrian, an Assyrian poet, commentator, preacher and defender of orthodoxy, joined the general exodus of Christians and reestablished the school on more securely Roman soil at Edessa. In the 5th century the school became a center of Nestorian Christianity, and was closed down by Archbishop Cyrus in 489; the expelled masters and pupils withdrew once more, back to Nisibis, under the care of Barsumas, who had been trained at Edessa, under the patronage of Narses, who established the statutes of the new school. Those that have been discovered and published belong to Osee, the successor of Barsumas in the See of Nisibis, and bear the date 496; they must be substantially the same as those of 489. In 590 they were again modified. The monastery school was under a superior called Rabban ("master"), a title also given to the instructors. The administration was confided to a majordomo, who was steward, prefect of discipline and librarian, but under the supervision of a council. Unlike the Jacobite schools, devoted chiefly to profane studies, the school of Nisibis was above all a school of theology. The two chief masters were the instructors in reading and in the interpretation of Holy Scripture, explained chiefly with the aid of Theodore of Mopsuestia. The free course of studies lasted three years, the students providing for their own support. During their sojourn at the university, masters and students led a monastic life under somewhat special conditions. The school had a tribunal and enjoyed the right of acquiring all sorts of property. Its rich library possessed a most beautiful collection of Nestorian works; from its remains Ebed-Jesus, Bishop of Nisibis in the 14th century, composed his celebrated catalogue of ecclesiastical writers. The disorders and dissensions, which arose in the sixth century in the school of Nisibis, favoured the development of its rivals, especially that of Seleucia; however, it did not really begin to decline until after the foundation of the School of Baghdad (832). Among its literary celebrities mention should be made of its founder Narses; Abraham, his nephew and successor; Abraham of Kashgar, the restorer of monastic life; John; Babai the Elder.

Islamic period

The city was taken without resistance by the forces of the Rashidun Caliphate under Umar in 639 or 640. Under early Islamic rule, the city served as a local administrative centre. In 717, it was struck and affected by an earthquake and in 927 it was raided by the Qarmatians. Nisibis was captured in 942 by the Byzantine Empire but was subsequently recaptured by the Hamdanid dynasty. It was attacked by the Byzantines once again in 972. Following the Hamdanids, the city was administered by Marwanids and Uqaylids. From the middle of the 11th century onwards, it was subjected to Turkish raids and the threat of County of Edessa, being attacked and damaged by Seljuq forces under Tughril in 1043. The city nevertheless remained an important centre of commerce and transport.[14]

In 1120, it was captured by the Artuqids under Necmeddin Ilgazi, followed by the Zengids and Ayyubids. The city is described as a very prosperous one by the period's Arab geographers and historians, with imposing baths, walls, lavish houses, a bridge and a hospital. In 1230, the city was invaded by the Mongol Empire. Mongol sovereignty was followed by that of the Ag Qoyunlu, Kara Koyunlu and Safavids. In 1515, it was taken by the Ottoman Empire under Selim I thanks to the efforts of Idris Bitlisi.[14]

Modern history

On the eve of World War I, Nusaybin had a small Armenian community of some 90 people, along with a large Jewish population numbering 600.[15]

As agreed upon by French and Turkish authorities after World War I, the border between Turkey and Syria would follow the line of the Baghdad Railway until Nusaybin, after which the border would follow the path of a contested Roman road leading to Cizre.[16]

Nusaybin was a place on the transit routes of Syrian Jews leaving the country after 1948. Upon reaching Turkey, after a route that took them through Aleppo and the Jazira sometimes with the help of Bedouin smugglers, most headed for Israel.[17] There was a big Jewish community in Nisbis since antiquity, many of them moved to Qamishli in the 20th century because of economic reason, there is a synagogue in Jerusalem that practices the rite of Nisbis and Qamishli.

Nusaybin made headlines in 2006 when villagers near Kuru uncovered a mass grave, suspected of belonging to Ottoman Armenians and Assyrians.[18] Swedish historian David Gaunt visited the site to investigate its origins, but left after finding evidence of tampering.[19][20] Gaunt, who has studied 150 massacres carried out in the summer of 1915 in Mardin, said that the Committee of Union and Progress's governor for Mardin, Halil Edip, had likely ordered the massacre on 14 June 1915, leaving 150 ethnic Armenians and 120 ethnic Assyrians dead. The settlement was then known as Dara (now Oğuz). Gaunt added that the death squad, named El-Hamşin (meaning "fifty men"), was headed by officer Refik Nizamettin Kaddur. The president of the Turkish Historical Society, Yusuf Halaçoğlu, said that the remains dated back to Roman times, although many people in the Turkish government openly deny the genocide even happened.[21] Özgür Gündem says that the military and police have pressed the media not to report the discovery.[22]

Recent developments

The Turkish Interior Ministry looked into dissolving Nusaybin's city council in 2012 because the body sought to use Arabic, Armenian, Aramaic, and Kurdish on signposts in the town, in addition to Turkish.[23]

In November 2013, Nusaybin's mayor, Ayşe Gökkan, commenced a hunger strike to protest against the construction of a wall between Nusaybin and its neighboring city of Qamishli in Syria. Construction of the wall stopped as a result of this and other protests.[24]

On 13 November 2015, the town was placed under a curfew by the Turkish government, and Ali Atalan and Gülser Yıldırım, two elected members of the Grand National Assembly from the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), began a hunger strike in protest. Two civilians and ten PKK fighters were killed by security forces.[25] As of March 2016, PKK forces controlled about half of Nusaybin according to Al-Masdar News[26] and the YPS controlled "much" of it, according to The Independent.[27] Following eight successive curfews over several months and clashes between the Turkish army and Kurdish militants, much of the city was destroyed and 61 Turkish soldiers were killed as of 1 May 2016.[28] As of 9 April, 60,000 residents of the city had been displaced, yet 30,000 civilians remained in the city, including in the 6 neighborhoods where the operations continued.[29] YPS reportedly had 700-800 militants in the city,[29] of which the Turkish army claimed that 325 were "neutralised" by 4 May.[30]

Economy

As a result of the Syrian civil war, the city's border with Syria (and more specifically the large Syrian city of Qamishli) has been closed, with claims that the cessation in cross-border trade and commuting has led to a 90% rise in unemployment in the city.[31]

Geography

Nusaybin is immediately north of the border with Syria, opposite the Syrian city of Al-Qamishli. The Jaghjagh River flows through both cities. The border between Al-Qamishli and Turkey is filled with land mines, with a total of some 600,000 having been placed between the countries in the 1950s as part of Turkey's efforts to protect NATO's southeastern edge.

Climate

Nusaybin has a semi-arid climate with extremely hot summers and cool winters. Rainfall is generally sparse.

| Climate data for Nusaybin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

22 (72) |

30 (86) |

37 (99) |

41 (106) |

40 (104) |

35 (95) |

28 (82) |

20 (68) |

13 (55) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

22 (72) |

28 (82) |

32 (90) |

31 (88) |

27 (81) |

21 (70) |

13 (55) |

8 (46) |

18.5 (65.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3 (37) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

16 (61) |

9 (48) |

5 (41) |

13.4 (56.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51 (2.01) |

30 (1.18) |

35 (1.38) |

26 (1.02) |

16 (0.63) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

12 (0.47) |

19 (0.75) |

34 (1.34) |

223 (8.78) |

| Average rainy days | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 41 |

| Source: Weather2[32] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Nusaybin is predominantly Kurdish, belonging to the Islamic faith. The city's population has close ties with the neighboring town of Qamishli and cross-border marriages are a common practice.[33][34] The city has a small Arabic population.[35] A very small Assyrian population remains in the city; what remained of the Assyrian population emigrated during the Kurdish-Turkish conflict of 1990s and as a result of the conflict in 2016, only one Assyrian family reportedly remained in the city.[36][37]

Religion

Christianity

The Roman Catholic Church has established no less than four successor titular archbishoprics, for various rites - one Latin and four Eastern Catholic for particular churches sui iuris. They are included in the Catholic Church's list of titular see of archiepiscopal rank notably for the Chaldean Catholic Church and the Maronite Catholic Church.[38]

Furthermore, when the Syriac Catholic Eparchy of Hassaké was promoted to archiepiscopal rank, at added Nisibi(s) to its name, becoming the Syriac Catholic Archeparchy of Hassaké-Nisibi (not Metropolitan, directly dependent on the Syriac Catholic Patriarch of Antioch).

Latin titular see: Established in the 18th century as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Romans).

It has been vacant for several decades, having previously had the following incumbents, all of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank :

- Giambattista Braschi (1724.12.20 – 1736.11.24)

- José Bolaños Calzado, Discalced Franciscans (O.F.M. Disc.) (1738.11.24 – 1761.04.07)

- Cesare Brancadoro (1789.10.20 – 1800.08.11) (later Cardinal)*

- Lorenzo Caleppi (1801.02.23 – 1816.03.08) (later Cardinal)*

- Vincenzo Macchi (1818.10.02 – 1826.10.02)(later Cardinal)*

- Carlo Luigi Morichini (1845.04.21 – 1852.03.15) (later Cardinal)*

- Vincenzo Tizzani, C.R.L. (1855.03.26 – 1886.01.15) (later Patriarch)*

- Johann Gabriel Léon Louis Meurin, Jesuits (S.J.) (1887.09.15 – 1887.09.27)

- Giuseppe Giusti (1891.12.14 – 1897.03.31)

- Federico Pizza (1897.04.19 – 1909.03.28)

- Francis McCormack (1909.06.21 – 1909.11.14)

- Joseph Petrelli (1915.03.30 – 1962.04.29)

- José de la Cruz Turcios y Barahona, Salesians (S.D.B.) (1962.05.18 – 1968.07.18)

Armenian Catholic titular see: Established as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Armenians) in 1910?.

It was suppressed in 1933, having had a single incumbent, of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank :

- Gregorio Govrik, Mechitarists (C.A.M.) (1910.05.07 – 1931.01.26)

Chaldean Catholic titular see: Established as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Chaldeans) in the late 19th century, suppressed in 1927, restored in 1970.

It has had the following incumbents, all of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank :

- Giuseppe Elis Khayatt (1895.04.22 – 1900.07.13)

- Hormisdas Etienne Djibri (1902.11.30 – 1917.08.31)

- Thomas Michel Bidawid (1970.08.24 – 1971.03.29)

- Gabriel Koda (1977.12.14 – 1992.03)

- Jacques Ishaq (2005.12.21 – ...), Bishop of Curia emeritus of the Chaldean Catholic Patriarchate of Babylon

Maronite titular see: Established as Titular Archiepiscopal see of Nisibis (informally Nisibis of the Maronites) in 1960. It is vacant, having had a single incumbent of the (intermediary) archiepiscopal rank:

- Pietro Sfair (1960.03.11 – 1974.05.18)

Transportation

Nusaybin is served by the E90 roadway and other roads to surrounding towns. The Nusaybin Railway Station is served by 2 trains per day. The closest airport is the Kamishly Airport 5 kilometers south from Nusaybin, located in Al Qamishli in Syria. The closest Turkish airport is the Mardin Airport, 55 kilometers northwest of Nusaybin.

See also

References

- ↑ "DBP'nin kayyum atanan belediyeleri" (in Turkish). BBC Turkish. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ↑ Darke, Diana (2014). Eastern Turkey. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 279.

- ↑ "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Mechanisms of Communication in the Assyrian Empire. "People, gods, & places." History Department, University College London, 2009. Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ↑ http://tuikapp.tuik.gov.tr/adnksdagitapp/adnks.zul

- ↑

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. "Nisibis." Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. Assyrian Eponym List. Accessed 18 Dec 2010.

- ↑ Talmud, Sanhedrin 32b

- ↑ Cowan, Ross (2009). "The Battle of Nisibis, AD 217". Ancient Warfare. 3.5: 29–35. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ Iranica: IRAQ i. IN THE LATE SASANID AND EARLY ISLAMIC ERAS

- ↑ Jonsson, David J. (2005). The Clash of Ideologies. Xulon Press. p. 181. ISBN 1-59781-039-8.

- 1 2 "Nusaybin". İslam Ansiklopedisi. 33. Türk Diyanet Vakfı. 2007. pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: a Complete History. London: Tauris. p. 378.

- ↑ Altuğ, Seda and Benjamin Thomas White (Jul–Sep 2009). "Frontières et pouvoir d'État: La frontière turco-syrienne dans les années 1920 et 1930". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire.

- ↑ Simon, Reeva, Michael M. Laskier, and Sara Reguer (2003). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 328.

- ↑ Oruc, Berguzar (2006-10-19). The bodies are suspected to be victims of the %5b%5bArmenian Genocide%5d%5d and %5b%5bAssyrian Genocide%5d%5d, by order of Ottoman Turkey during World War 1. "Ermeni köyu'nde toplu mezar" Check

|url=value (help). Dicle Haber (in Turkish). Özgür Gündem. Retrieved 2008-09-23. - ↑ Gunaysu, Ayse (2006-11-07). "Toplu mezar Ermeni ve Süryanilere ait". Özgür Gündem (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Belli, Onur Burcak (2007-04-27). "Truth of mass grave eludes Swedish professor". Turkish Daily News. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ "Toplu mezarla yüzleşme vakti". Özgür Gündem (in Turkish). 2006-12-13. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Oruc, Berguzar (2006-10-22). "Toplu mezar gizleniyor". Dicle Haber. Özgür Gündem. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Gusten, Susanne (2012-03-21). "Sensing a Siege, Kurds Hit Back in Turkey". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ↑ "Solidarity with Nusaybin Mayor Ayse Gokkan". www.jadaliyya.com. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ↑ 2 HDP deputies go on hunger strike to end days-long Nusaybin curfew dated November 19, 2015, at todayszaman.com, accessed 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "Kurds capture 50% of Turkish city on the border with Syria". Al-Masdar News. 2016-03-23.

- ↑ "Nusaybin, the Turkish city where war is now a way of life". The Independent. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nusaybin'den son görüntüler" (in Turkish). NTV. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Vali devre dışı, Nusaybin'i asker yönetecek: 30 bin sivil...". Cumhuriyet. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nusaybin'de PKK'ya ağır darbe!". Milliyet. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21564870-fiercely-anti-assad-stance-turkey-taking-syria-aggravating-long-running-troubles Turkey, Syria and the Kurds: South by south-east

- ↑ http://www.myweather2.com/City-Town/Turkey/Nusaybin/climate-profile.aspx

- ↑ "How Bashar Assad Has Come Between the Kurds of Turkey and Syria". Time. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Yıldırım, Ayşe (2013), Devlet, Sınır, Aşiret: Nusaybin Örneği (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Turkish), Hacettepe University, retrieved 6 May 2016

- ↑ Halifeoğlu, Fatma Meral (2006). "SAVUR GELENEKSEL KENT DOKUSU İLE SOSYAL YAPI İLİŞKİSİ ÜZERİNE BİR İNCELEME". Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 5 (17): 76–84. ISSN 1304-0278.

- ↑ "Son Süryaniler de göç yolunda". Evrensel. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nusaybin'in son Süryani ailesi: Terk etmeyeceğiz". Evrensel. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 941]

Sources and External links

- Nisibis, Catholic Encyclopedia

- GCatholic, Armenian Catholic titular see

- GCatholic, Chaldean Catholic titular see

- GCatholic, Latin Catholic titular see

- GCatholic, Maronite titular see

- , Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review

- The Battle of Nisibis, AD 217