Naval artillery in the Age of Sail

| Part of a series on |

| Cannon |

|---|

|

| History |

| Operation |

| By country |

| By type |

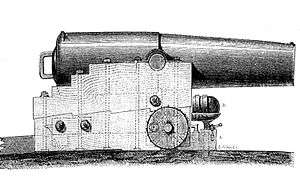

Naval artillery in the Age of Sail encompasses the period of roughly 1571–1862: when large, sail-powered wooden naval warships dominated the high seas, mounting a bewildering variety of different types and sizes of cannon as their main armament. By modern standards, these cannon were extremely inefficient, difficult to load, and short ranged. These characteristics, along with the handling and seamanship of the ships that mounted them, defined the environment in which the naval tactics in the Age of Sail developed.

Firing

.jpg)

Firing a naval cannon required a great amount of labour and manpower. The propellant was gunpowder, whose bulk had to be kept in a special storage area below deck for safety. Powder boys, typically 10–14 years old, were enlisted to run powder from the armory up to the gun decks of a vessel as required.

A typical firing procedure follows. A wet swab was used to mop out the interior of the barrel, extinguishing any embers from a previous firing which might set off the next charge of gunpowder prematurely. Gunpowder was placed in the barrel, either loose or in a cloth or parchment cartridge pierced by a metal 'pricker' through the touch hole, and followed by a cloth wad (typically made from canvas and old rope), then rammed home with a rammer. Next the shot was rammed in, followed by another wad to prevent the cannonball from rolling out of the barrel if the muzzle was depressed. The gun in its carriage was then 'run out'; men heaved on the gun tackles until the front of the gun carriage was hard up against the ship's bulwark, the barrel protruding out of the gun port. This took the majority of the gun crew manpower, as the weight of a large cannon in its carriage could total over two tons, and the ship would probably be rolling.

The touch hole in the rear (breech) of the cannon was primed with finer gunpowder (priming powder) or from a quill (from a porcupine or the skin-end of a feather) pre-filled with priming powder, then ignited.

The earlier method of firing a cannon was to apply a linstock—a wooden staff holding a length of smoldering match at the end—to the touch-hole of the gun. This was dangerous and made accurate shooting difficult from a moving ship, as the gun had to be fired from the side to avoid its recoil, and there was a noticeable delay between the application of the linstock and the gun firing.[1] In 1745, the British began using gunlocks (flintlock mechanisms fitted to cannon).

The gunlock, by contrast, was operated by pulling a cord or lanyard. The gun-captain could stand behind the gun, safely beyond its range of recoil, and sight along the barrel, firing when the roll of the ship lined the gun up with the enemy, and so reduce the chance of the shot hitting the sea or flying high over the enemy's deck.[1] Despite their advantages, gunlocks spread gradually as they could not be retrofitted to older guns. The British adopted them faster than the French, who had still not generally adopted them by the time of the Battle of Trafalgar (1805),[1] placing them at a disadvantage, as the new technology was in general use by the Royal Navy at this time. After the introduction of gunlocks, linstocks were retained, but only as a backup means of firing.

The linstock slow match or the spark from the flintlock ignited the priming powder, which in turn set off the main charge, which propelled the shot out of the barrel. When the gun discharged, the recoil sent it backwards until it was stopped by the breech rope, a sturdy rope made fast to ring bolts let into the bulwarks, with a turn taken about the gun's cascabel (the knob at the end of the gun barrel).

A typical broadside of a Royal Navy ship of the late 18th century could be fired 2–3 times in approximately 5 minutes, depending on the training of the crew, a well trained one being essential to the simple yet detailed process of preparing to fire. The British Admiralty did not see fit to provide additional powder to captains to train their crews, generally only allowing 1/3 of the powder loaded onto the ship to be fired in the first six months of a typical voyage, barring hostile action. Instead of live fire practice, most captains exercised their crews by "running" the guns in and out, performing all the steps associated with firing but without the actual discharge. Some wealthy captains, those who had made money capturing prizes or who came from wealthy families, were known to purchase powder with their own funds to enable their crews to fire real discharges at real targets.

Artillery types

A complete and accurate listing of the types of naval guns requires analysis both by nation and by time period. The types used by different nations at the same time often were very different, even if they were labelled similarly. The types used by a given nation would shift greatly over time, as technology, tactics, and current weapon fashions changed.

Some types include:

One descriptive characteristic which was commonly used was to define guns by their pound rating — theoretically, the weight of a single solid iron shot fired by that bore of cannon. Common sizes were 42-pounders, 36-pounders, 32-pounders, 24-pounders, 18-pounders, 12-pounders, 9-pounders, 8-pounders, 6-pounders, and various smaller calibres. French ships used standardized guns of 36-pound, 24-pound, 18-pound, 12-pound, and 8-pound calibers, augmented by carronades and smaller pieces. In general, larger ships carrying more guns carried larger ones as well.

The muzzle-loading design and weight of the iron placed design constraints on the length and size of naval guns. Muzzle-loading required the cannon to be positioned within the hull of the ship for loading. The hull width, guns lining both sides, and hatchways in the centre of the deck also limited the room available. Weight is always a great concern in ship design as it affects speed, stability, and buoyancy. The desire for longer guns for greater range and accuracy, and greater weight of shot for more destructive power, led to some interesting gun designs.

Long nine

One unique naval gun was the long nine. It was a proportionately longer-barrelled 9-pounder. It was typically mounted as a bow or stern chaser where it was not perpendicular to the keel, and this also allowed room to operate this longer weapon. In a chase situation, the gun's greater range came into play. However, the desire to reduce weight in the ends of the ship and the relative fragility of the bow and stern portions of the hull limited this role to a 9-pounder, rather than one which used a 12- or 24-pound shot.

Carronade

The carronade was another compromise design. It fired an extremely heavy shot but, to keep down the weight of the gun, it had a very short barrel, giving it shorter range and lesser accuracy. However, at the short range of many naval engagements, these "smashers" were very effective. Their lighter weight and smaller crew requirement allowed them to be used on smaller ships than would otherwise be needed to fire such heavy projectiles. It was used from the 1770s to the 1850s.

Paixhans gun

The Paixhans gun (French: Canon Paixhans) was the first naval gun using explosive shells. It was developed by French general Henri-Joseph Paixhans in 1822–1823 by combining the flat trajectory of a gun with an explosive shell that could rip apart and set on fire the bulkheads of enemy warships. The Paixhans gun ultimately doomed the wooden sailship, and forced the introduction of the ironclad after the Battle of Sinop in 1853.

Shot

In addition to varying shot weights, different types of shot were employed for various situations:

- Round shot –Solid spherical cast-iron shot, the standard fare in naval battles.

- Canister shot – Cans filled with dozens of musket balls. The cans broke open on firing to turn the gun into a giant shotgun for use against enemy personnel.

- Grapeshot – Canvas-wrapped stacks of smaller round shot which fitted in the barrel, typically three or more layers of three. Some grape shot was made with thin metal or wood disks between the layers, held together by a central bolt. The packages broke open when fired and the balls scattered with deadly effect. Grape was often used against the enemy quarterdeck to kill or injure the officers, or against enemy boarding parties.

- Chain-shot – Two iron balls joined together with a chain. This type of shot was particularly effective against rigging, boarding netting, and sails, since the balls and chain would whirl like bolas when fired.

- Bar shot – Two balls or hemispheres joined by a solid bar. Their effect was similar to chain shot.

- Expanding bar shot – Bar shot connected by a telescoping bar which extended upon firing.

- Link shot – A series of long chain links which unfolded and extended upon firing.

- Langrage – Bags of any junk—scrap metal, bolts, rocks, gravel, old musket balls, etc., fired to injure enemy crews.

- Fire arrows – A thick dartlike incendiary projectile with a barbed point, wrapped with pitch-soaked canvas which took fire when the gun was fired. The point stuck in sails, hulls, or spars and set fire to the enemy ship.

- Heated shot – Shore forts sometimes heated iron shot red-hot in a special furnace before loading it (with water-soaked wads to prevent it from setting off the powder charge prematurely). The hot shot lodging in a ship's dry timbers would set the ship afire. Because of the danger of fire aboard, heated shot were seldom used aboard ships.

- Double shot – Two round shot or other projectiles loaded in one gun and fired at the same time. Double-shotting lowered the effective range and accuracy of the gun, but could be devastating within pistol shot range—that is, when ships drew close enough for a pistol shot to reach between the two ships. To avoid bursting the gun, reduced powder charges were used. Guns sometimes were double-shotted with canister or grape on top of ball, or even triple-shotted with very small powder charges which still were enough to cause horrible wounds at close range.

- Exploding shell – Ammunition that worked like a grenade, exploding and sending shrapnel everywhere, either by a burning fuse which was cut to a calculated length depending on the range, or (after 1861) on contact with the target. Shells were often used in mortars, and specialized and reinforced "bomb vessels" (often ketch-rigged so that there was less rigging to obstruct the high-angle mortar shell) were adapted to fire huge mortars for shore bombardment. The "bombs bursting in air" over Fort McHenry in the American national anthem were this type of projectile.

See also

- Age of Sail

- Cannon

- Naval tactics in the Age of Sail

- Carronade

- Naval long gun

- Howitzer

- Naval artillery

- List of cannon projectiles

References

- 1 2 3 Rodger, Nicholas (2004). The Command of the Ocean:A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815. Penguin Books. p. 420. ISBN 0-14-028896-1.

Further reading

- Howard, Frank, "Early Ship Guns. Part I: Built-up Breech-loaders", Mariner's Mirror 72 (1986), pp. 439–53.

- Howard, Frank, "Early Ship Guns. Part II: Swivels", Mariner's Mirror 73 (1987), pp. 49–55.

- Rodger, Nicholas A. M., "The Development of Broadside Gunnery, 1450-1650." Mariner's Mirror 82, No. 3 (1996), pp. 301–24.

- Rodger, Nicholas, "Image and Reality in Eighteenth-Century Naval Tactics." Mariner's Mirror 89, No. 3 (2003), pp. 281–96.