Morus (plant)

| Mulberry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Morus nigra | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Moraceae |

| Tribe: | Moreae[1] |

| Genus: | Morus L. |

| Species | |

|

See text. | |

Morus, a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, comprises 10–16 species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions.[2]

The closely related genus Broussonetia is also commonly known as mulberry, notably the paper mulberry, Broussonetia papyrifera. Mulberries are fast-growing when young, but soon become slow-growing and rarely exceed 10–15 metres (30–50 ft) tall. The leaves are alternately arranged, simple and often lobed and serrated on the margin. Lobes are more common on juvenile shoots than on mature trees.

The trees can be monoecious or dioecious.[3][4] The mulberry fruit is a multiple fruit, approximately 2 to 3 cm (one inch) long. Immature fruits are white, green, or pale yellow. In most species the fruits turn pink and then red while ripening, then dark purple or black, and have a sweet flavor when fully ripe. The fruits of the white-fruited cultivar are white when ripe; the fruit of this cultivar is also sweet, but has a very bland flavor compared with darker varieties.

Species

The taxonomy of Morus is complex and disputed. Over 150 species names have been published, and although differing sources may cite different selections of accepted names, only 10–16 are generally cited as being accepted by the vast majority of botanical authorities. Morus classification is even further complicated by widespread hybridisation, wherein the hybrids are fertile.

The following species are accepted by the Kew Plant List as of August 2015:[5]

- Morus alba L. – White mulberry (China, Korea, Japan)

- Morus australis Poir. – Chinese mulberry (China, Japan, Indian Subcontinent, Myanmar)

- Morus cathayana Hemsl. – China, Japan, Korea

- Morus celtidifolia Kunth – (N + S America)

- Morus indica - L. – India, Southeast Asia

- Morus insignis - Bureau – Central America and South America

- Morus japonica Audib. – Japan

- Morus liboensis S.S. Chang – Guizhou Province in China

- Morus macroura Miq. – Long mulberry (Tibet, Himalayas, Indochina)

- Morus mesozygia Stapf – African mulberry (S and C Africa)

- Morus mongolica (Bureau) C.K. Schneid. – China, Mongolia, Korea, Japan

- Morus nigra L. – Black mulberry (Iran)

- Morus notabilis C.K. Schneid. – Yunnan + Sichuan Provinces in China

- Morus rubra L. – Red mulberry (E N America)

- Morus serrata Roxb. – Tibet, Nepal, northwestern India

- Morus trilobata (S.S. Chang) Z.Y. Cao – Guizhou Province in China

- Morus wittiorum Hand.-Mazz. – southern China

Distribution and cultivation

Black, red, and white mulberry are widespread in southern Europe, the Middle East, northern Africa and Indian subcontinent, where the tree and the fruit have names under regional dialects. Jams and sherbets are often made from the fruit in this region. Black mulberry was imported to Britain in the 17th century in the hope that it would be useful in the cultivation of silkworms. It was much used in folk medicine, especially in the treatment of ringworm. Mulberries are also widespread in Greece, particularly in the Peloponnese, which in the Middle Ages was known as Morea, deriving from the Greek word for the tree (μουριά, mouria).

Mulberries can be grown from seed, and this is often advised as seedling-grown trees are generally of better shape and health, but they are most often planted from large cuttings which root readily. The mulberry plants which are allowed to grow tall with a crown height of 5–6 feet from ground level and a stem girth of 4–5 inches or more is called tree mulberry. They are specially raised with the help of well-grown saplings 8–10 months old of any of the varieties recommended for rain-fed areas like S-13 (for red loamy soil) or S-34 (black cotton soil) which are tolerant to drought or soil-moisture stress conditions. Usually, the plantation is raised and in block formation with a spacing of 6 feet × 6 feet, or 8 feet × 8 feet, as plant to plant and row to row distance. The plants are usually pruned once a year during the monsoon season (July – August) to a height of 5–6 feet and allowed to grow with a maximum of 8–10 shoots at the crown. The leaves are harvested three or four times a year by a leaf-picking method under rain-fed or semiarid conditions, depending on the monsoon.

The tree branches pruned during the fall season (after the leaves have fallen) are cut and used to make durable baskets supporting agriculture and animal husbandry.

Some North American cities have banned the planting of mulberries because of the large amounts of pollen they produce, posing a potential health hazard for some pollen allergy sufferers.[6] In actuality, only the male mulberry trees produce pollen; this light-weight pollen can be inhaled deeply into the lungs, sometimes triggering asthma.[7][8] Conversely, female mulberry trees produce all-female flowers, which draw pollen and dust from the air. Because of this pollen-absorbing feature, all-female mulberry trees have an OPALS allergy scale rating of just 1 (lowest level of allergy potential), and some consider it "allergy-free".[7]

Fortunately, mulberry tree scion wood can easily be grafted onto other mulberry trees during the winter, when the tree is dormant. One common scenario is converting a problematic male mulberry tree to an allergy-free female tree, by grafting all-female mulberry tree scions to a male mulberry that has been pruned back hard.[9] However, any new growth from below the graft(s) must be removed, as they would be from the original male mulberry tree.[10]

Uses

The fruit of the white mulberry – an East Asian species extensively naturalized in urban regions of eastern North America – has a different flavor, sometimes characterized as refreshing and a little tart, with a bit of gumminess to it and a hint of vanilla.[11][12] In North America, the white mulberry is considered an invasive exotic and has taken over extensive tracts from native plant species, including the red mulberry.[13]

The ripe fruit is edible and is widely used in pies, tarts, wines, cordials, and tisanes. The fruit of the black mulberry (native to southwest Asia) and the red mulberry (native to eastern North America) have the strongest flavor, which has been likened to 'fireworks in the mouth'.[11]

The fruit and leaves are sold in various forms as nutritional supplements. The mature plant contains significant amounts of resveratrol, particularly in stem bark.[14] Unripe fruit and green parts of the plant have a white sap that may be toxic, stimulating, or mildly hallucinogenic.[15]

Nutritional profile

In a 100-g (3.5-oz) serving, raw mulberries provide 43 Calories, 44% of the Daily Value (DV) for vitamin C, and 14% of the DV for iron (table). Other nutrients are in insignificant quantity (table).

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 179.912 kJ (43.000 kcal) |

|

9.8 | |

| Sugars | 8.1 |

| Dietary fiber | 1.7 |

|

0.39 | |

|

1.44 | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

(0%) 1 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(3%) 0.029 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(8%) 0.101 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(4%) 0.62 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

(4%) 0.05 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(2%) 6 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(44%) 36.4 mg |

| Vitamin E |

(6%) 0.87 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(7%) 7.8 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium |

(4%) 39 mg |

| Iron |

(14%) 1.85 mg |

| Magnesium |

(5%) 18 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(5%) 38 mg |

| Potassium |

(4%) 194 mg |

| Sodium |

(1%) 10 mg |

| Zinc |

(1%) 0.12 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Water | 87.68 g |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Silk industry

Mulberry leaves, particularly those of the white mulberry, are ecologically important as the sole food source of the silkworm (Bombyx mori, named after the mulberry genus Morus), the cocoon of which is used to make silk.[16][17] Other Lepidoptera larvae—which include the common emerald, the lime hawk-moth, and the sycamore moth—also sometimes eat the plant.

Pigments

Mulberry fruit color derives from anthocyanins, which are under basic research for mechanisms of various diseases.[18][19] Anthocyanins are responsible for the attractive colors of fresh plant foods, including orange, red, purple, black, and blue. These colors are water-soluble and easily extractable, yielding natural food colorants. Due to a growing demand for natural food colorants, their significance in the food industry is increasing.

A cheap and industrially feasible method has been developed to extract anthocyanins from mulberry fruit which could be used as a fabric tanning agent or food colorant of high color value (above 100). Scientists found that, of 31 Chinese mulberry cultivars tested, the total anthocyanin yield varied from 148 to 2725 mg per liter of fruit juice.[20] All the sugars, acids, and vitamins of the fruit remained intact in the residual juice after removal of the anthocyanins, so the juice could be used to produce products such as juice, wine, and sauce.

Anthocyanin content depends on climate and area of cultivation, and is particularly high in sunny climates.[21] This finding holds promise for tropical countries that grow mulberry trees as part of the practice of sericulture to profit from industrial anthocyanin production through the recovery of anthocyanins from the mulberry fruit.

This offers a challenging task to the mulberry germplasm resources for

- exploration and collection of fruit yielding mulberry species

- their characterization, cataloging, and evaluation for anthocyanin content by using traditional, as well as modern, means and biotechnology tools

- developing an information system about these cultivars or varieties

- training and global coordination of genetic stocks

- evolving suitable breeding strategies to improve the anthocyanin content in potential breeds by collaboration with various research stations in the field of sericulture, plant genetics, and breeding, biotechnology and pharmacology

Paper

During the Angkorian age of the Khmer Empire of Southeast Asia, monks at Buddhist temples made paper from the bark of mulberry trees. The paper was used to make books, known as kraing.[22]

In culture

A Babylonian etiological myth, which Ovid incorporated in his Metamorphoses, attributes the reddish-purple color of the mulberry fruits to the tragic deaths of the lovers Pyramus and Thisbe. Meeting under a mulberry tree (probably the native Morus nigra),[23] Thisbe commits suicide by sword after Pyramus was killed by the lioness because he believed that Thisbe was eaten by her. Their splashed blood stained the previously white fruit, and the gods forever changed the mulberry's colour to honour their forbidden love.[23]

The nursery rhyme "Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush" uses the tree in the refrain, as do some contemporary American versions of the nursery rhyme "Pop Goes the Weasel".

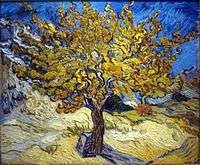

Vincent van Gogh featured the mulberry tree in some of his paintings, notably Mulberry Tree (Mûrier, 1889, now in Pasadena's Norton Simon Museum). He painted it after a stay at an asylum, and he considered it a technical success.[24]

Gallery

- Clusters (inflorescences) of unopened female flower buds

Morus nigra male flowers

Morus nigra male flowers Unripe white mulberries

Unripe white mulberries Female flower clusters

Female flower clusters Mulberry Tree by Vincent van Gogh, 1889

Mulberry Tree by Vincent van Gogh, 1889

References

- ↑ "Morus L.". Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ Suttie JM. "Morus alba L.". Plant Production and Protection. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Red Mulberry". Northeastern Area State & Private Forestry - USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ Zhengyi Wu, Zhe-Kun Zhou & Michael G. Gilbert. "Flora of China". Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ↑ The Plant List, search for Morus

- ↑ "City of El Paso agenda item, July 10, 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- 1 2 Ogren, Thomas Leo (2000). Allergy-Free Gardening. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 1580081665.

- ↑ Wilson, Charles L. "Tree pollen and hay fever". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ Ogren, Thomas Leo (2003). Safe Sex in the Garden : and Other Propositions for an Allergy-Free World. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 1580083145.

- ↑ Phipps, Nikki. "Can Grafted Trees Revert to Their Rootstock?". gardeningknowhow.com. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- 1 2 The Cloudforest Gardener

- ↑ Mulberry

- ↑ Boning, Charles R. (2006). Florida's Best Fruiting Plants: Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. p. 153.

- ↑ Cui XQ, Wang HQ, Liu C, Chen RY (July 2008). "Study of anti-oxidant phenolic compounds from stem barks of Morus yunanensis" [Study of anti-oxidant phenolic compounds from stem barks of Morus yunanensis]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi (in Chinese). 33 (13): 1569–72. PMID 18837317.

- ↑ "White mulberry, Morus alba". Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide. The Ohio State University. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Ombrello, T. "The mulberry tree and its silkworm connection". Department of Biology, Union County College, Cranford, NJ. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Mulberry silk". Central Silk Board, Ministry of Textiles - Govt of India. 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Wrolstad RE (2001). "The possible health benefits of anthocyanin pigments and polyphenolics". Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Hou DX (March 2003). "Potential mechanisms of cancer chemoprevention by anthocyanins". Current Molecular Medicine. 3 (2): 149–59. doi:10.2174/1566524033361555. PMID 12630561.

- ↑ Liu X, Xiao G, Chen W, Xu Y, Wu J (2004). "Quantification and Purification of Mulberry Anthocyanins with Macroporous Resins". Journal of Biomedicine & Biotechnology. 2004 (5): 326–331. doi:10.1155/S1110724304403052. PMC 1082888

. PMID 15577197.

. PMID 15577197. - ↑ Matus JT, Loyola R, Vega A, et al. (2009). "Post-veraison sunlight exposure induces MYB-mediated transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin and flavonol synthesis in berry skins of Vitis vinifera". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (3): 853–67. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern336. PMC 2652055

. PMID 19129169.

. PMID 19129169. - ↑ Prof. K. R. Chhem and M. R. Antelme (2004). "A Khmer Medical Text "The Treatment of the Four Diseases" Manuscript". Siksācakr, Journal of Cambodia Research. 6: p.33–42.

- 1 2 Reich, Lee (2008). "Morus spp. mulberry". In Janick, Jules; Paull, Robert E. The Encyclopedia of Fruit and Nuts. CABI. pp. 504–507. ISBN 9780851996387.

- ↑ Gogh, Vincent van (1889). "Mulberry Tree". van Gogh Collection. Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Morus (Moraceae) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morus. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Mulberry. |

- Flora of China: Morus

- Flora of North America: Morus

- Sorting Morus names (University of Melbourne)

- Propagation (growing) by vegetative method

- Propagation (growing) by seed method

- photo of 300-year-old Japanese mulberry

- Central Sericultural Germplasm Resources Centre, Ministry of Textiles, Government of India

- Replant a mulberry tree: article from Times of India