Mount St Bernard Abbey

|

Mount St Bernard Abbey | |

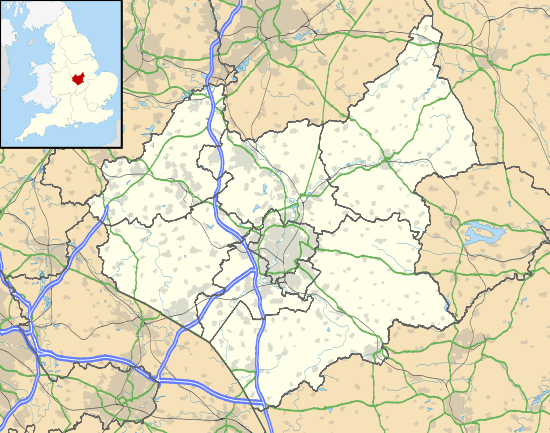

Location within Leicestershire | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Cistercian Trappists |

| Established | 1835 |

| Abbot | The Rt Rev Dom Erik Varden OCSO |

| Site | |

| Location | Near Coalville, Leicestershire, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 52°44′29″N 1°19′23″W / 52.741352°N 1.323072°WCoordinates: 52°44′29″N 1°19′23″W / 52.741352°N 1.323072°W |

| Public access | yes |

Mount St Bernard Abbey is a Cistercian monastery of the Strict Observance (Trappists) near Coalville in Leicestershire, England, formerly in the parish of Whitwick and now of that in Charley, in Charnwood Forest, founded in 1835. The abbey has the distinction of being the first permanent monastery to be founded in England since the Reformation.

Background

The early history of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey is inextricably linked with an earlier, short-lived foundation of Cistercian monks in Lulworth, Dorset and the Abbey of Mount Melleray in Ireland. Following the suppression of monasteries in France, a small colony of dispossessed Cistercian monks had arrived in London in 1794, with the intention of moving on to found a monastery in Canada. Their plight came to the attention of Thomas Weld of Lulworth Castle, Dorset, a Catholic convert and philanthropist who distinguished himself in relieving the misfortunes of refugees of the French Revolution and who then provided them with land on which to establish a monastic community on his estate in East Lulworth.[1]

The monks remained at Lulworth until 1817, when they returned to France to re-establish the ancient monastery of Melleray in Brittany, following the restoration of the Bourbons. This affair was short-lived however, when during the French Revolution of 1830, the monks were again persecuted and left to found Mount Melleray Abbey in Ireland (1833). It was from the Irish monastery of Mount Melleray that a small colony of monks was dispatched to found the monastery of Mount Saint Bernard in 1835.

The Cistercian order itself dates back to the 12th century and the Trappists to the mid-17th century. Mount St Bernard is the only abbey belonging to this order left in England.

History

Mount St Bernard Abbey was founded in 1835 on 222 acres (0.90 km2) of land purchased from Thomas Gisborne MP, by Ambrose Lisle March Phillipps De Lisle, a local landowner and Roman Catholic convert who wanted to re-introduce monastic life to the country. De Lisle was especially attracted to the Cistercians because his family mansion at Garendon had replaced a former Cistercian monastery. [2]

The land that the monks took possession of in September 1835 was wild and largely uncultivated, but it contained an ancient enclosure known as Tin Meadow, and it was into the near-derelict Tin Meadow House, a small four-roomed cottage, that the first monks came to make their home. The first monks were Augustine, Luke, Xavier, Cyprian, Placid, Simeon and Fr Odilo Woolfrey.[3]

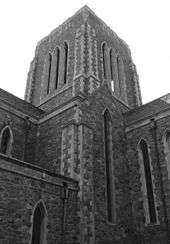

Work was then begun on a temporary monastery, which was opened in 1837, to the designs of William Railton, an architect most famed today for having designed Nelson's Column in London. In 1844, a new, permanent monastery was opened on the site where it still stands, through donations from John Talbot, 16th Earl of Shrewsbury, and other benefactors. It was designed by Augustus Pugin, who offered his services free of charge. 'The whole of the buildings', wrote Pugin, 'are erected in the greatest severity of the lancet style, with massive walls and buttresses, long and narrow windows, high gables and roofs, with deeply arched doorways. Solemnity and simplicity are the characteristics of the monastery, and every portion of the architecture and fittings corresponds to the austerity of the Order for whom it has been raised'.

Pugin's monastery church however, was only partially completed due to a lack of funds. Only the nave, in fact, was completed, which was then walled off at the point where Pugin had planned a crossing tower with spire, and eastern chancel. A makeshift two bell turret was fashioned over the eastern gable of the unfinished church, so that the monks could be called to office. The church was then to remain unfinished for more than ninety years.[4]

The monastery is sheltered immediately on the north side by a large outcrop, which was once known as Kite Hill.[5] According to an early publication with a foreword by Abbot Burder (1852), this site would also have been the preferred location for the original monastery designed by Railton, but soon after the purchase of the land, there had been some dispute as to whether the rock belonged to the monastic grounds or to the parish of Whitwick. Huge opposition to the founding of the monastery had been mounted by Francis Merewether, Vicar of Whitwick,[6][7] and parish authorities had apparently "spoke of holding parties of pleasure upon the rock and of over looking the monks". The county constable was eventually called in to resolve the dispute, and gave a decision in favour of the monks, whereafter opponents were obliged to refrain "from any further molestation of the religious in the erection of their new monastery".[8] A calvary was subsequently erected upon the summit of the rock, and this is now open to the public, and reached by a winding footpath, with an ascent aided by stone steps fashioned by the monks.

It was during the early cultivation of the monastery estate, on 2 June 1840, that Lay Brother John Patrick McDanell, together with labourers William Hickin and Charles Lott, unearthed an urn with their plough, which contained approximately 2000 Roman coins, "conglomerated together, and covered with the green oxide of copper".[9] The coins were subsequently identified as being from the time of Gallienus and Tetricus I, who lived in the third century AD, and the find inevitably led to speculation that the land may have been inhabited during Roman times. Writing in 1852, Father Robert Smith noted that, "Besides the coins, there was discovered a small arrow or spear-head, three inches long. Also a small round article, having the appearance of a Roman lamp, and composed of terra-cotta. Pieces of Roman vases, and pottery, were [also] found in great abundance". Father Robert believed that these finds and the presence of "several ancient mounds" in the immediate vicinity clearly indicated that there had been a Roman military post here.[10] The fact that the site of the hoard's discovery occupied "one of the highest spots in the forest, [commanding] a very extensive view of the surrounding country" was also felt to lend credence to this theory.[9] However, more recent historians have tended to the idea that the hoard may have been placed here 'in hiding' and eventually forgotten about. The remaining coins are now housed at the Newarke Houses Museum in Leicester.[11][12]

The fame of the new monastery soon grew and attracted many thousands of sightseers. Amongst the many famous visitors to the infant monastery were William Wordsworth and Florence Nightingale. Many illustrious English clergymen also came, such as Nicholas Wiseman, John Henry Newman, Henry Edward Manning, William Bernard Ullathorne and George Stanley Faber and the monastery also drew famous writers and men of affairs from abroad, including Montalembert, Lacordaire, Dollinger and the Comte de Chambord.[3]

Wordsworth, who visited in 1841, wrote: "[We] drove to a part of Charnwood Forest where they are erecting a monastery for Trappists. The situation is chosen with admirable judgment, a plain almost surrounded with wild rocks, not lofty but irregularly broken, and in one quarter is an opening to a most extensive prospect of cultivated country. The building is austere and massy, and when the whole shall be completed, the chapel is not yet begun, the effect will be most striking in the midst of that solitude. Several monks were at work in the adjoining Hayfields, working most industriously in their grey woolen gowns, one with his cowl up, and others, Lay brethren I believe, clothed in black".[13]

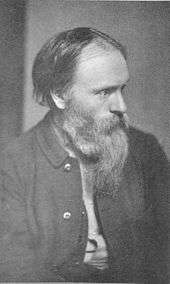

Another person of national renown known to have visited the fledgling monastery was the Pre-Raphaelite artist, Edward Burne-Jones, as a youth, in 1851. Burne-Jones chanced to visit the abbey whilst staying with relatives, who had moved to a cheese farm close by.[14] The experience was to have a profound impact on him and forty-five years later he wrote: "I get no time to myself - not five minutes ever in the day- and I am growing angry. . . . More and more my heart is pining for that monastery in the Charnwood Forest. Why there? I don't know, only that I saw it when I was little and have hankered after it ever since".[15]

After his death in 1898, his widow wrote: "Though it is doubtful whether he ever saw the place again with his bodily eyes, the thought of it accompanied him throughout his whole life. Friends, wife, and children all knew the undercurrent of longing for the rest and peace which he thought he had seen there that day; he did not disguise it from them, and in his later years often spoke of the dream which had walked step by step with him ever since, of somehow leaving every one and everything and entering its doors and closing them behind him."[16]

Charles Dickens is also reputed to have spent some time in retreat at the abbey,[17] though he is not enumerated amongst the list of celebrated visitors in the monastery's 'Brief Historical Sketch'.[3] It is certain however, that he took an interest in the abbey, and is known to have sent two of his employees, Edmund Yates and Thomas Speight there, to pen articles about the monastery for publication in his weekly magazines, All The Year Round and Household Words[4] The noted architect and inventor of the Hansom cab, Joseph Hansom also visited during the 1850s, and many years later, one of his grandsons was to join the community, taking the name Brother Alban, where he died from influenza in 1919.[18]

In addition to its many famous visitors, the monastery has - throughout its history - been a place of refuge for the poor and hungry. Luigi Gentili, a priest associated with De Lisle's mission, wrote that there were extremes of rural poverty to be found in Leicestershire that could not be matched, even in the most poverty-stricken parts of his native Italy.[3] This number was greatly increased by the influx of many Irish immigrants fleeing from the Great Potato Famine of the 1840s. So great was the scale of the poverty during this period that the monks were feeding many thousands of people each year. In 1845, 2,788 people were given lodgings at the monastery and 18,887 were given food.[19] In 1847, "36,000 people received charity and hospitality from the hands of the monks".[20]

In 1848, the monastery was granted the status of an abbey by Pope Pius IX and its first abbot was appointed, Dom Bernard Palmer. It was united with the Cistercian congregation by a papal brief in 1849.

In 1856 a reformatory school for young Catholic delinquents was founded at Mount Saint Bernard, and which was housed in the original monastery built by Railton (now demolished). This was known as the Saint Mary's Agricultural Colony, commonly referred to locally as simply, 'The Colony' or the "Bad Lads' Home".[21][22] It closed in 1881 after several episodes of disorder, but re-opened temporarily in 1884-5 to house boys who had burnt and sunk their own reformatory ship, HMS Clarence, moored in the Mersey.[23] During its lifetime, it was calculated that a total of 1,642 boys had been admitted to the institution.[24]

Today all trace of the reformatory building has gone, though the Colony Reservoir - a small upland lake - remains a short distance from the site, on the Charnwood Lodge Nature Reserve (SK464152).[25] As the names suggests, this was used to supply water to the reformatory, or 'colony', and the inmates of the establishment are credited with having excavated it.[26] A large wooden cross marks the reformatory graveyard, in which forty two people are buried - either boys or other servants of the reformatory.[27]

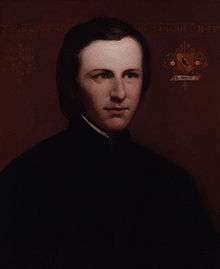

In 1862 John Rogers Herbert painted Laborare est Orare (To labour is to pray), which depicted "the monks of Saint Bernard's Abbey, Leicestershire, gathering in the harvest of 1861, assisted by some of the boys from a neighbouring reformatory in their care"[28] This painting was purchased by the Tate Gallery in 1972. Due to the fact that this painting clearly depicts a church building with a tower and spire, it has invariably been argued that Herbert's portrait does not represent Mount Saint Bernards, as the abbey was without a tower until the twentieth century and has never had a spire. However, the catalogue entry for this painting at the Tate Gallery explains that Herbert used Pugin's original designs to depict the church in line with the architect's vision. Herbert was a close friend of Pugin and had painted him in 1845, in a portrait which now hangs in the Palace of Westminster.[29] Moreover, the abbey guest book confirms that "Mr. Herbert, an artist from London" visited the abbey on July 22, 1861.[30] The artist also depicted himself executing the painting, in the extreme foreground.

In 1878, the Leicestershire coalfield suffered a severe depression in trade, resulting in much distress being caused to the miners and their families. Large numbers of the unemployed workforce made their way to the monastery on a daily basis, where soup in large quantities was gratuitously supplied.[31] This practice was repeated on a similar scale during the General Strike of 1926.[32]

The abbey suffered from financial problems and a lack of monks joining the community through the 19th century. This improved in the 20th century and the church was extended between 1935 and 1939 from the designs of Albert Herbert, FRIBA of Leicester, although it was not consecrated until 1945, by the Bishop of Nottingham. However, the church was not completed in accordance with the designs of Pugin, who had planned a conventional ecclesiastical arrangement, with a chancel at the east end, containing the high altar. The new design, overseen by Abbot Malachy Brasil, saw the altar placed centrally, under the crossing tower, with a second nave for the public placed at the east end, where Pugin's chancel would have been. This design attracted significant criticism at the time, but Abbott Malachy is now recognized as having been many years ahead of his time in having conceptualized such a scheme.[33]

Following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, members of the monastic profession were initially exempt from military service, but as the pool of potential recruits diminished, the War Office altered its ruling, which resulted in the conscription of six of the brothers from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey in 1917. Three of them were passed as fit for foreign service, whilst the other three undertook service at home. This represented a considerable loss to the monastery as at that time it had only twenty monks in residence - the smallest number since its foundation eighty-two years previously.[34]

It was reported that Leslie Hore-Belisha, the former Secretary of State for War, had stayed at the abbey in 1942. Mr Hore-Belisha subsequently explained to the Evening Standard that he felt it was important "to have an occasional period of retirement and reflection on the ultimate reasons behind existence".[35] The private papers of Hore-Belisha show that in actual fact, he stayed at the abbey regularly - once for a period of nine weeks.[36]

Blessed Cyprian Michael Iwene Tansi was a monk at the abbey from 1950 until his death in 1964. He was buried at the abbey but his remains were later moved to his native Nigeria, where he was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 22 March 1998.[37] A wall sculpture by Leicester Thomas, commemorating the life of Father Cyprian, has been erected in the public nave of the abbey church.[38]

In 1952, the remains of twenty six Cistercian monks were exhumed by workmen on the Monastery Farm estate at Lulworth. These were then re-interred at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey.[39]

In 1957, the actor Sir Alec Guinness made the first of many retreats to Mount Saint Bernard Abbey following his conversion to Roman Catholicism the year previously.[40] Guinness mentions his first stay at the abbey in his 1986 autobiography, Blessings in Disguise, in which he describes attending a dawn mass:

Arriving at the large, draughty, austere white chapel, I was amazed at the sights and sounds that greeted me. The great doors to the East were wide open and the sun, a fiery red ball, was rising over the distant farmland; at each of the dozen or so side-altars a monk, finely vested but wearing heavy farmer's boots to which cow dung still adhered, was saying his private Mass. Voices were low, almost whispers, but each Mass was at a different stage of development, so that the Sanctus would tinkle from one altar to be followed ... other tinkles from far away. For perhaps five minutes little bells sounded from all over and the sun grew whiter as it steadily rose. There was an awe-inspiring sense of God expanding, as if to fill every corner of the church and the whole world.The regularity of life at the abbey, the happy faces that shone through whatever they had suffered, the strong yet delicate singing, the early hours and hard work. All made a deep impression on me; the atmosphere was one of prayer without frills; it was easy to imagine oneself at the centre of some spiritual powerhouse, or at least being privileged to look over the rails, so to speak, at the working of a great turbine.[41]

Another notable actor remembered for his periods of retreat at the abbey was Ian Bannen, who had been schooled at Ratcliffe College in Leicestershire.[42]

In the late 1950s, huge public outcry was generated by the proposed route of the M1 motorway through Charnwood Forest. On 15 November 1957, the Leicester Evening Mail wrote: "The Trappist monks went to Charnwood for peace and built the beautiful St. Bernard's Monastery. The proposed route would pass their door step if allowed to go on". Through the Evening Mail, a petition was organised and two months later the newspaper reported: "Many of the monks at Mount St. Bernard Monastery, in Charnwood, have taken a lifelong vow of silence, and therefore they are unable to speak their views on the proposed Forest motorway, which would pass within half a mile of their peaceful home. This has not prevented them from reading of the protest petition and signing it, however. Seventeen have put their names on a form sent to the monastery this week, including the Father Abbot".[43]

The petition which was eventually presented to the Ministry of Transport, which led to the rerouting of the road on to its present course.[44]

In 1978, Mount Saint Bernard Abbey was visited by the New York-based artist, Stanley Roseman. The abbey was amongst the first of more than sixty monastic communities to be visited by Roseman over a period of several years. Whilst at Mount Saint Bernard, he painted "Father Benedict: Portrait of a Trappist Monk" and "Father Ian: Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Meditation". The latter now hangs in the Musée Ingres in Montauban.[45]

The buildings were listed as Grade II in 1989,[46] though in an architectural and historical review of more than 140 churches prepared for English Heritage and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Nottingham, April 2011, it was noted in the case of St Bernard's: "There is a strong case for upgrading the complex, or at least the abbey church, from II to II* both on grounds of architectural significance and for its historic importance in the Catholic Revival".[47]

The role of acceptance that the abbey has played in offering succor to the troubled and those in need of friendship was emphasised by reports in 1998 that the footballer Justin Fashanu had sought solace there in the final days of his life.[48][49]

In 2009, the skeletons of more than six hundred medieval Trappist monks were re-buried in the grounds of Mount Saint Bernard. The remains had originally been found by workmen excavating an extension to London Underground's Jubilee line in 1998, on a site which had once been occupied by Stratford Langthorne Abbey. This had been one of the wealthiest monasteries in England, closed in Henry VIII's dissolution in 1538.[50]

After the interment of the final bones at a special ceremony on 29 July 2009, a talk was given in the abbey church by the abbot, Dom Joseph Delargy in which he explained: "You notice on the memorial stone is just inscribed, 'St. Mary's Abbey, Stratford Langthorne', and not, 'the remains from'. This is to symbolize the fact that the abbey is the people, not the buildings. Seeing as all the human remains from the abbey are now all here, is not the 'abbey' now here?" [51]

Following the discovery of the remains of King Richard III in 2012, Mount Saint Bernard Abbey was proposed as a suitable place for his bones to be housed until agreement could be reached on a permanent resting place. Members of the 'Looking For Richard' team, headed by Philippa Langley claimed that the University of Leicester had agreed to release the remains once scientific testing had been finished, so that they might be placed in a "prayerful environment", prior to reburial. A Catholic site was felt to be particularly appropriate since Richard had been a pre-Reformation (and thereby Catholic) monarch, and had originally been laid to rest in the monastic church of Greyfriars, Leicester. In 2014, Dr John Ashdown-Hill, genealogist with Langley's team, told the Leicester Mercury, "The site originally proposed for this was Mount St Bernard's Abbey, which is not far from Leicester. This would be a very suitable place for King Richard to lie in peace, surrounded by the prayers of the monks, pending his reinterment." The University however claimed that this agreement had not been legally binding and declined to release the king's remains, which were finally reinterred in the Anglican Cathedral of Leicester, on March 26, 2015. The monks of Saint Bernard reacted impartially to the dispute and when contacted by the Mercury newspaper, a spokesperson said it was felt that the community was not in a position to comment on the situation.[52]

Abbots and Superiors, 1835 to Present

| Abbot/Superior | Dates of Office |

|---|---|

| Superior: 1835 - 39 | |

| Superior: 1839 - 41 | |

| Superior: 1841 - 49; Abbot: 1849 -52 | |

| Superior: 1852 - 53; Abbot: 1853 - 58 | |

| Superior: 1859 - 63; Abbot: 1863 - 90 | |

| Abbot: 1890 - 1910 | |

| Superior: 1910 - 27 | |

| Superior: 1927 - 29; Abbot: 1929 - 33 | |

| Abbot: 1933 - 59 | |

| Abbot: 1959 - 74 | |

| Abbot: 1974 - 80 | |

| Superior: 1980 - 82; Abbot: 1982 - 2001 | |

| Abbot: 2001 - 13 | |

| Superior 2013 - 15; Abbot 2015 - | |

Initially, the monastery of Mount Saint Bernard was subject to the jurisdiction of the Very Reverend Vincent Ryan, Abbot of Mount Melleray in Ireland, which was regarded as the mother house of the new settlement.[64]

The small, founding colony of monks at Mount Saint Bernard was originally led by Father Odilo Woolfrey, who also assumed the duties of parish priest for the neighbouring Catholic churches of Grace Dieu and Whitwick.[32] Odilo's brother, Father Norbert Woolfrey also came to Saint Bernards and acted for a while as parish priest at Loughborough.[65] Both brothers later embarked on missionary work in Australia. Odilo Woolfrey died on 31 March 1856, and is buried with his brother Norbert, in the churchyard of St Thomas Becket's, Lewisham, Sydney.[53]

In September 1839, Abbot Ryan sent over Father Benedict Johnson, who had been cellarer of Mount Melleray, to replace Father Odilo as superior. Reports had apparently reached Abbot Ryan that Father Odilo was introducing 'strange practices' and that the lay-brothers had become practically choir monks.[66] Father Benedict, who had originally joined the monastery at Lulworth in 1813,[67] died at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey in 1850. A member of the community subsequently wrote: "Never will the writer of these lines forget the fervent manner in which he thanked God, a few moments before his death, for having called him to the holy state of religion, and for having given him the grace of perseverance to the last hour of his life".[68]

He was succeeded as superior in 1841 by John Bernard Palmer, who had entered the monastery at Lulworth in 1808. He had left with the community for Melleray in 1817, but in 1836 was asked to join the new community of Mount Saint Bernard. In 1848, the monastery became an abbey and Dom Bernard Palmer was elected as its first abbot. Dom Bernard is described as having been, "a simple, almost unlettered man but one who was known for his holiness and deep purity of life. He was the unanimous choice of his brethren as their first abbot. He was, until his death in 1852, the only mitred abbot in England, and the 'Abbot of Mount Saint Bernard' was widely known, but it was for his humility, charity and love for the poor that he was most widely recognised and esteemed".[3]

Abbot Palmer was buried in a vault beneath the chapter-room of the abbey. His remains were re-interred in the cloister garth a century later, alongside the remains of monks previously interred at Lulworth. The Lulworth monks were re-interred on either side of Abbot Palmer's grave: the brothers on his left, and the priests on his right.[55]

On the death of Abbot Palmer, the subprior, Father Bernard Burder, was appointed provisional superior and was elected as second abbot in 1853.[3] Burder was a grandson of George Burder, a famous non-conformist divine and editor of the Evangelical Magazine.[57] His father, Henry Forster Burder was also a non-conformist minister and had been a co-founder of the Congregational Union.

Bernard Burder's tenure as abbot proved to be somewhat unsettled. A convert Anglican clergyman, Abbot Burder had considered that the rigorous Trappist life was too hard for Englishmen and had made plans for separating the monastery from the Trappist General Chapter and affiliating it to the Benedictines. In addition, many of the monastic community had become profoundly disturbed by the way in which a nearby boys' reformatory, begun by the abbot in 1856, had begun to affect the life of the monastery. The outcome was inevitable and the abbot resigned his office in 1858, following an enquiry by papal commission.[3] After several attempts to join monastic communities, and spells as a private chaplain, Bernard Burder died at Lulworth Castle in September 1881.[69]

In 1859, Father Bartholemew Anderson was appointed superior, being elected abbot in 1863, and was to lead the community for thirty years - the longest tenure of any monk, as head of the community. Three of his brothers were also monks of Mount Saint Bernard.[3] Abbot Anderson oversaw a number of additions made to the monastery buildings, including the Clock Tower and the octagonal Chapter House. He also had a particular interest in ecumenicalism and was involved with the Association for the Promotion of the Unity of Christendom. The extension of such courtesy to non-Catholics was unusual at that time and among the guests welcomed by the abbot was the prime minister, William Gladstone, who paid a special visit in 1873.[3] Two members of the community at this time were particularly well-known: Brother Anselm Baker, a noted heraldic artist, and Father Austin Collins, a writer of books and hymns.[3]

In 1890, Dom Wilfred Hipwood became abbot. Described as a gentle and scholarly man, he had formerly been a professor at St Mary's College, Oscott.[70] His twenty years as abbot were marred by almost constant ill-health, and he was confined to his room during the last ten years of his life. His tenure also saw a decline in numbers; by the time of his death in 1910, the community numbered fewer than thirty monks.[3]

In 1910, Father Louis Carew was sent to Mount Saint Bernard as provisional superior. In 1889, Father Louis had been appointed as superior of New Melleray Abbey in Iowa[71] and later became a definitor of the order. Noted for the firmness of his discipline, an indication of the regard in which he was held occurred in 1915, when John Hedley, Bishop of Newport and Menevia summoned Father Louis as his director, to prepare him for death.[70] However, numbers continued to remain low during his period of governance. Father Louis died in 1927, whilst on holiday in Ireland.[3]

Father Louis was succeeded as superior of Mount Saint Bernard by the prior of Mount Melleray Abbey, Father Celsus O'Connell. The community began to grow almost immediately and by 1929 it was again possible to hold an abbatial election at the monastery. Dom Celsus was elected as the new abbot, but after only four years, he moved back to Mount Melleray, when he was elected abbot of that house.[3]

Fortunately, the monastery's revival continued under his successor, Dom Malachy Brasil - the third Irishman to rule the abbey, who took charge in 1933, elected as abbot by the monks of Mount Saint Bernard on the basis of his excellent reputation, gained as prior of Roscrea. It was during Dom Malachy's time that the abbey attained its present day form, with the completion of the abbey church, just over one hundred years after the foundation of the monastery. This and other noteworthy achievements of Dom Malachy is described in his obituary, written by the monks of Nunraw:

"His first move, we were informed, was to call in an outsider to improve the chant and discharge of the divine office. After examining the accounts and revenue of the abbey he planned the building of the monastic church. Already Pugin, the famous architect of the nineteenth century had designed a small church of which the nave had been completed. There it stood for nearly a century unfinished. With admirable courage the new superior changed the plans and built practically another church twice the size of what was previously designed. There were critics, of course, of the monastic edifice with a nave in the east and one in the west with the altar in the centre. Since Vatican II however, visitors to the monastery say that Dom Malachy was a century ahead of his time. Next he beautified the grounds, enlarged the guesthouse and brought it up-to-date. Not a year passed during his time as superior that did not witness improvements made in both the buildings and farm. During this period the personnel of the community also increased and reached the highest ever. He received subjects, professed them and had a large number of his monks raised to the priesthood. When eventually he laid aside the pastoral staff in 1959 he left to his successor a flourishing abbey".[33]

It is also noted that it was during Dom Malachy's abbacy that the community was joined by the first Nigerians to become Cistercian monks.[3]

Dom Malachy resigned in 1959, having celebrated his silver jubilee as abbot and spent his final years at the Cistercian monastery of Sancta Maria Abbey, Nunraw in Scotland, where he was laid to rest in 1965.[72]

The new abbot, Father Ambrose Southey, was the first Englishman to govern the abbey for more than half a century. During the period of his office, the community made a foundation in the West Cameroons - the monastery of Our Lady of Bamenda, founded in 1963 - now an independent community composed mainly of African monks. Dom Ambrose was already abbot vicar of the order when, in 1974 he was elected abbot general, the highest office in the order.[3] Dom Ambose stepped down as Abbot-General in 1990 and later became superior of Bamenda Abbey (Cameroon) which he served from 1993 until 1996, and superior of Scourmont Abbey (Belgium), from 1996 until 1998. Dom Ambrose later accepted the ministry of chaplain for the community of Vitorchiano and remained there until he returned definitively to his "community of stability", Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, where he died on 24 August 2013, aged ninety years.[73]

In 1974, the monastery elected their prior, Father Cyril Bunce as abbot, and who was succeeded by John Moakler in 1980, in turn succeeded by Dom Joseph Delargy in 2001.

Following his retirement as Abbot in 2001, Dom John Moakler was made Abbot Emeritus and later took up the position of chaplain at Holy Cross Abbey in Whitland, Wales.[74]

Dom Joseph Delargy retired as abbot in June 2013, after completing two six-year terms. Following a short sabbatical in India, Father Joseph then assumed duties as the Abbey Guestmaster[75]

The subsequent abbatial election was inconclusive, and Norwegian-born Father Erik Varden was appointed Superior ad nutum (i.e. with the agreement of the community).[76] On 16 April 2015, Dr Erik Varden became the eleventh abbot of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, following a further election,[77] also becoming the first abbot to have been born outside Britain or Ireland.

Abbot Varden gained his Master’s and a theological doctorate at Cambridge University, prior to joining the abbey in 2002. He is also a musician and studied Gregorian Chant under Dr Mary Berry, later co-founding the Chant Forum with Dame Margaret Truran of Stanbrook Abbey. After entering the monastic profession, he went to Rome to study for a second doctorate in Syriac studies.[78] On 23 April 2011, Father Erik Varden sang the Exsultet during the Easter Vigil in the Vatican Basilica, in the presence of Pope Benedict XVI.[79]

In 2015, Dr Varden was interviewed as part of a BBC Four documentary, Saints and Sinners: Britain's Millennium of Monasteries, by Dr Janina Ramirez[80]

Notable monks

A number of monks at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey have attained a measure of celebrity beyond the sphere of their cloister. Other than Blessed Cyprian Tansi or those who became abbots or superiors, they are summarized here.

- Anselm Baker (1834 - 1885) - Heraldic artist. Joined the abbey in 1857. About two-thirds of the coats-of-arms in Foster's Peerage were drawn by him, and are signed 'F.A.' (Frater Anselm). He also executed the mural paintings in the chapel of Atherstone Priory; in St Winifred's, Shepshed; in the Temple in Garendon Park, and in the Lady and Infirmary chapels at Saint Bernard's. Buried in the abbey graveyard.

- Henry Augustine Collins (1827 - 1919) - Hymnist. Ordained an Anglican priest in 1853, Henry Collins subsequently converted to the Roman Catholic Church and joined Mount Saint Bernard Abbey in 1861, where he became known as Father Austin. He composed a number of well-known hymns, among them 'Jesus, my Lord, my God, my all'. Buried in the abbey graveyard.[81]

- Hilary Costello (born 1926) - Writer. Born in London. During World War Two, Father Hilary was conscripted into the coal mines as a "Bevin Boy", where he worked from 1943 until 1947, when he joined the abbey. After he was ordained in 1955, he began to work on the transcription of medieval manuscripts and has distinguished himself in this field, having produced numerous books and articles about the Cistercian Fathers and similar subjects. Has for some years been the abbey's bookbinder. His most recent book (2015) is a translation of the First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre.[82]

- Vincent Eley - Sculptor/Woodcarver/Potter. Author of "A Monk at the Potter's Wheel: The Story of Charnwood-Cistercian Ware" (Edmund Ward, 1952). After attending a course in pottery at Loughborough School of Art, he established a workshop complete with kiln and other appliances at the monastery and began to produce wares modelled chiefly on the sturdy designs of the English medieval tradition.[83] This is continued at the abbey to the present day, under the direction of Brother Martin Howarth, a German-born member of the community.[84] Some of Father Vincent's work was displayed in the South Bank exhibition at the Festival of Britain.[85] Also responsible for sculpting the statues which surmount the Calvary, and other features.

- Robert Henry Smith (1807 - 1866) - Writer. Entered the abbey in 1848 and for some time was Superior of the reformatory school there. Was the author of two books and translator of four others, including the first English translation of St John Climacus’ "The Holy Ladder of Perfection" (1858),[86] which runs to nearly 500 pages. Father Robert also wrote, "A Concise History of the Cistercian Order" (1852), which gives a valuable insight into the early development of the abbey.[87]

The monks of Mount Saint Bernard have become renowned for their longevity and length of service to the community. Father Peter Logue (1913 - 2010) was reported to have been the oldest monk ever to have been at the abbey when he died at the age of 96, having been a monk there for 75 years.[88] This record has since been surpassed by Brother Gabriel Manogue (1914 - 2013), who died on 6 July 2013 aged 99 years, after 74 years at the abbey.[89][90]

Present day

The monks get up at 3:15 am every day and go to bed at 8:00 pm. Until the late twentieth century, the monks slept in long dormitories, but now have their own cells, enabling greater solitude and individual prayer.[91]

The three focuses of monastic life at Mount St Bernard Abbey are prayer, work and reading with study. They take part in daily liturgical prayer, known as Opus Dei or Canonical Hours. They meditatively read the Bible, which is called Lectio Divina. Silence and solitude are very important to the order and the abbey. Their work includes the production of pottery, bookbinding, beekeeping and tending the vegetable garden and orchard. They also run a gift shop where they sell the items that they make in the abbey. The abbey has a guesthouse for friends and family of the monks, retreatants and those who are interested in the monastic life.

Until recently the monks ran a 200-acre (0.81 km2) dairy farm, though this has been one of approximately ten thousand dairy farms that have been forced to close across the United Kingdom since 2005, as a result of falling milk prices.[92] This has deprived the community of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey of its principal source of revenue and the monks are currently looking into the viability of establishing a brewery at the abbey as an alternative enterprise, in line with a well-established tradition of similar monasteries in Europe.[93] Trappist beer is currently produced by eleven other monasteries - six in Belgium, two in the Netherlands and one each in Austria, Italy and United States.[94] There are various accounts which indicate that beer was brewed by the monks of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey throughout the nineteenth century,[95][96] the earliest of these occurring in 1847, when it was reported that the monks here produced a beer "of purity and excellence".[97]

In keeping with the tradition of the Cistercian Order, the monks live on a vegetarian diet. Writing in 1955, Dr Douglas Latto of Harley Street suggested that the monks of Mount Saint Bernard enjoyed "excellent health" and longevity as a result. Latto wrote that whilst a monastic lifestyle was likely to be beneficial to health due to reduced levels of stress, religious communities differed markedly in health depending on their diet. To support this, he cited a study by Saile, who took the blood pressure of 100 Carthusian, Cistercian, and Carmelite monks, all meat abstainers and found it considerably lower than a similar number of Benedictine monks - meat eaters.[98]

Any monk that dies at Mount Saint Bernard will end up in the monastery's communal coffin. The coffin comes out purely for funerals, and then is returned to the abbey's attic.[91] In accordance with Cistercian burial rites, monks are buried without a coffin. The hood of the cowl is folded over the face and the body is then lowered into the ground where it is received into the arms of an infirmarian, who then arranges it in a final loving service. The abbot places the first shovelful of earth on the body, after which his brothers fill the grave by shoveling earth onto the body's feet, letting it gradually and indirectly encompass the body, after which all withdraw.[99]

Life at the Abbey was briefly shown in Richard Dawkins' 2012 television programme Sex, Death and the Meaning of Life.[100]

Mount St Bernard Abbey maintains an ecumenical link with the Anglican Cistercians, a dispersed and uncloistered order of single, celibate, and married men that is officially recognized within the Church of England.[101]

According to a BBC article of 2005, the monastery had a full quota of 35 brothers, with approximately 50 applications to join the monastery every year. It was also noted that in the region of 5000 guests stayed at the monastery annually. Guests can stay up to five days and there is no charge, although the abbey encourages visitors to make a contribution toward the running of the guest house.[91]

The Abbey Church and grounds

The Abbey Church of Mount Saint Bernard is dedicated to the Greater Glory of God, in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Bernard.[102]

The severe, undecorated Gothic style of the church is traditional in the Cistercian order, and can still be seen in the remnants of old Cistercian abbeys. Pugin borrowed largely from these remains in his efforts to reproduce their simple and austere beauty and personally supervised the construction of the western nave, which was completed in 1844.

The granite used to build the monastery was quarried by the monks in the monastery grounds. The Ketton stone came from Normanton Hall, whilst the Walldon stone came from Lord Ancaster's quarries. In 1839, the founder, Ambrose Phillipps de Lisle wrote: "The Monks have already commenced drawing the stone, and one of the Contractors for the Midland Counties railway has very generously given them enough iron rails to make a little Railway to their great granite rock from the spot on which the Monastery is to stand, so that by the help of a rope and a wind-lace with only one horse all the material except sand, lime, and free stone will be drawn. This is another mark of the divine protection in my opinion [and] besides this, you will be glad to hear that the proprietor of the Barrow lime works (not Barrow on Trent but Barrow-on-Soar) has given them gratis all the lime they will want for the whole edifice; is not this glorious?"[103]

In February 1934 work was begun on extending the abbey church, with eighty monks working continuously for four years on a project which saw the building lengthened from 90 feet to 220 feet. The architect was F.J Bradford of Leicester, who mirrored the western nave by Pugin, by continuing the church east by five bays, to make a nave for the laity and a monastic choir in the original nave.[2] The site of the extension was a sloping platform of solid rock, which was blasted away on one side and filled in on the other with mass concrete to provide a level foundation for the building.[104] A contemporary account noted that "The interior finish affords an outstanding example of the craft of cement rendering. All walls have been given three coats, using water-repellent cement, the final coat being in a cream cement mixture. The surfaces of the piers and walls have been scored with a piece of pointed wood to give the effect of masonry. Mica was incorporated in the final coat, the surface being left in a roughened state".[104]

Interior features:

None of the current fittings are associated with Pugin and following the completion of the abbey church, the community embraced a more modern approach to liturgical design, with contributions from several noted twentieth century designers and craftsmen.

The altar is of the same stone as the church and designed by David John. The altar top is of Clipsham stone from a quarry in Rutland. David John is an accomplished liturgical designer and sculptor whose other works include the statue of Our Lady in bronze at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral and the altar, tabernacle and lectern in the English College Chapel in Rome.[105]

The hanging pyx in which the Sacrament of the Body of Christ is reserved is of stainless steel and copper and was designed and made by Father Alban Buggins.

The wooden crucifix and the stone plaques over the side altars are the work of Father Francis O'Malley. O'Malley was a notable artist and follower of Eric Gill and was the first headmaster of Grace Dieu School, a preparatory school for Ratcliffe College founded in 1933.[106]

In the central boss of the church, above the central altar, are the three heraldic shields marking the dedication - one of the very few features of decoration. The arms are those of Pius XI, the reigning Pope at the completion of the church, the shield of Citeaux, and that of Mount Saint Bernard/Abbot Malachy.[107] The arms assumed for Mount Saint Bernard are: Or, a crozier in pale, with a sudarium sable; on a chief azure, three lions rampant or - the latter being the arms of the founder, De Lisle.[108]

The Choir stalls of 1938 were designed by Eric Gill and are ninety-eight in number. In 1958, these were provided with high backs to enhance acoustics.

The founder's tomb, namely that of Ambrose Phillipps de Lisle, can be found in the south aisle of the original (western) nave. His remains were interred in a vault beneath the altar of St Stephen Harding in 1878[109] and this was re-opened to receive the remains of his wife, Laura Clifford, in 1896.[110] Laura de Lisle was a sister of William Clifford, Bishop of Clifton.

The salve statue by Costa (1958), above the east porch, is of Mary and the Child Jesus and is copied from the seal of Furness Abbey, Lancashire.

The wall sculpture depicting Blessed Cyprian Tansi on the north wall of the public nave is by the British sculptor, Leicester Thomas. Elsewhere, an example of his work can be found in his 'Golfer of the Century' statue (Jack Nicklaus) at Ohio State University.[111]

The current pipe organ was installed in 2014 and was salvaged from a church in Munich. An organ was first installed in 1937, which had been made by Henry Willis and Sons and which comprised 1,140 pipes. This was later donated to the chapel of Ratcliffe College[112] and was eventually replaced by an Allen electronic organ, presented by the mother of Father Mark Hartley, an organist at the abbey for many years, on the occasion of his silver jubilee, in 1962.[113]

After fifty years of service, the electronic Allen organ had become noticeably past its prime but the community was not in a position to fund its replacement. Then, "something happened": in 2013, Stefan Heiß, a master organ builder from Bavaria and a friend of the abbey, informed the community that he had been offered a fine pipe organ with two manuals and sixteen registers from a Munich church scheduled for demolition and made an offer to oversee its restoration and reconstruction at the abbey. With the help of private donations, this was accomplished, with a new wooden case built to house the pipes on a platform above the central sanctuary. The outstanding costs of transporting the organ by lorry from Bavaria were aided by an inaugural concert performed by Joseph Cullen, sometime organist of Westminster Cathedral and Jennifer Smith (soprano), a professor of the Royal College of Music, following a special service on 8 June 2014.[114]

Abbey Church - Principal Statistics:

- Total length - 222 feet

- Total width - 43 feet

- Width at transepts - 94 feet

- Greatest interior height - 52 feet

- Sanctuary - 66 feet x 25 feet

- Choir Arches - 20 feet

- Central arches - 40 feet

- Height of tower - 100 feet

- Width of tower - 25 feet

- Walls throughout - 3 feet (excluding buttresses)

Exterior features:

The carved heads are by Robert Kiddey (1900–84), a well-known Newark based artist and sculptor,[115] and Father Vincent Eley. They represent four angels and eight famous Cistercians: Pope Eugene III; Cardinal Bona; St Peter of Tarentaise; St Aelred of Rievaulx; St Lutgardis of Aywières; Eleanor, Queen of Aragon; King Eric II of Norway, and Walter Espec, knight.

The armorial water heads are the coats of arms of twenty Cistercian monasteries dissolved by Henry VIII. These include: Garendon in Leicestershire; Fountains and Rievaulx in Yorkshire; Waverley in Surrey; Beaulieu in Hampshire; Tintern in Monmouth; Ford in Devon; Merevale in Warwickshire and Wardon in Bedfordshire.

The tower was designed by Albert Herbert FRIBA, FSA (1875 - 1964) of Leicester, noted for having also designed Lady Herbert's Garden in Coventry and for having overseen major extensions to Northampton Cathedral, between 1948 and 1955.[116] The tower is not surmounted with a spire as the original intention, because of technical difficulties and consequent extra expenses. Rising to a height of 100 feet, the tower has a dead weight of approximately 2000 tons and is supported on a concrete foundation.[104] The tower contains two bells, one weighing two tons and the other fifteen cwts, cast by Taylors of Loughborough in 1936 and which are swung slowly by means of an electrical mechanism.[117] The monastery's much smaller original bell, also cast by Taylor's foundry in 1852, was presented to the Roman Catholic church of Saint Peter, Leamington Spa, in 2005 for use as an angelus bell.[118]

Secular cemetery

In the monastery's secular cemetery can be found two plaques to the memory of Everard Aloysius Lisle Phillipps, VC (1835–57), who was the son of the abbey's founder. The original sandstone plaque is badly weathered and largely illegible and a more modern replacement has been fixed beneath it to perpetuate the inscription. It records the fact that he "performed valiantly at the Storming of the Water Bastion" in Delhi during the Indian Mutiny, 14 September 1857, and where he was killed three days later, being awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously.[119]

Vice-Admiral Robert Hall, CB, Third Sea Lord and veteran of the Crimean War, was buried here in 1882.[120]

James Tisdall Woodroffe, KCSG, a former Advocate-General of Bengal was buried here in 1908.

Caspar Pound (1970 - 2004), musician and founder of Rising High Records was laid to rest here with his father Pelham Pendennis Pound (1922 - 1999), a former features editor of the News of the World and who was also the father of the Labour politician Stephen Pelham Pound, MP.[121] Their simple monument carries the epitaph, "Rising High".

There are monuments to various well-known Roman Catholic families of the district, including the De Lisles of Garendon Park and Gracedieu Manor, and the Worsley Worswicks of Normanton Hall, Earl Shilton.

Calvary monument

A wooden calvary was first erected on the granite outcrop to the north of the abbey church on 20 August 1847. "A numerous congregation assembled on the occasion from the neighbourhood. They sat down in groups beneath the rock, whilst the Rev. Moses Furlong preached, from a set-off in the rock, about half way from its summit, and which accommodated him with a green sward, and a commanding position".[122] The original calvary existed until well into the twentieth century and an account of 1904 reads, "From almost every part of the forest the huge cross may be seen. It rises abruptly, awe inspiring and beautiful. The cross is of massive oak, 14 ft. in height, and is mortised into a stone pedestal, resting on a griece of three stone steps cut into the solid rock".[123]

The present "Gill-style" sculptures surmounting the calvary rock are the work of Father Vincent Eley, 1965,[2] and represent the crucified Jesus, mounted on a cross of concrete, with images of Our Lady and Saint John on either side.[124]

Chapel of Dolours

Located in an elevated position on the north side of the monastery, alongside the footpath which leads up to the calvary, can be found the tiny Chapel of Dolours, or Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. Originally built in 1842 from the designs of Pugin, this had formerly stood in Cademan Wood, Whitwick, which formed part of Ambrose de Lisle's Grace Dieu estate. Soon after being built, the chapel became referred to locally as "The Temple" and the part of Cademan Wood in which it stood also became known as Temple Wood. De Lisle had the chapel built after being inspired by similar examples of wayside shrines in Bavaria and it was designed to form part of a devotional walk on his land, which also comprised fourteen Stations of the Cross and a Calvary along the route.[125] The chapel contains "two most exquisite and remarkable figures executed by the celebrated sculptor, Petz of Munich, and representing in painted wood the Blessed Virgin weeping over her divine Son, who has just been taken down from the Cross, the nails being laid at his feet".[126] By the middle of the twentieth century, the chapel had succumbed to vandalism, having stood derelict for many years and in 1955, at the suggestion of Captain Ambrose de Lisle, it was dismantled and reassembled on its present site by the monks of Mount Saint Bernard.[32] The semi-circular foundations of the original Chapel of Dolours can still be found on an outcrop not far from the Man Within Compass public House in Whitwick and further trace of its memory can be found in the naming of Temple Hill, a residential road developed close by, around the time of the chapel's removal.[127]

E.W Pugin

Also in Cademan Wood - about a quarter of a mile away from site of the Temple - there is a mound, upon which are still to be seen the foundations of another wayside structure commissioned by De Lisle, built between 1863-64. This had been a tower, eighty feet in height, built as a memorial to De Lisle's son, Everard Aloysius Lisle March Phillips VC, and which became known locally as "The Monument". The surrounding woodland subsequently became known as "Monument Wood". The tower was designed by Edward Welby Pugin and was medieval in appearance, redolent of the Water Bastion in Delhi, where March Phillips had been killed during the Indian Mutiny of 1857. The tower was demolished, circa 1947.[128]

E.W Pugin - the eldest son of A.W.N Pugin - was also responsible for reconstruction of the Chapter House at Mount St Bernard's Abbey, in 1860. The chapter house, which is octagonal, with a matching conical roof, is a larger replacement of A.W.N Pugin's original. The chapter house contains one of the abbey's most treasured pieces of art, namely an early fifteenth century Flemish, life-size wooden figure of the Virgin. This had been found beneath the floorboards of a farmhouse and is thought to have originally been at Hailes Abbey, Gloucestershire.[2]

E.W Pugin also carried out extensions and alterations to abbey's guest house, which has a bell-cote, very similar to that at A.W.N Pugin's St Marie's Grange, near Salisbury.[128]

The younger Pugin may also have been responsible for the clock tower of 1871, and also the Lodge - a Grade II listed stone cottage on the monastery estate, which carries the date 1856 on a plaque.[129] This house, which stands close to the staggered cross-roads at Oaks in Charnwood, has an ornamental tiled roof and chamfered stone door and window surrounds, features which are thought to lend weight to the suggestion that it was designed by E.W Pugin. In the gable end which faces the main road, there is also a small statute of St Philip Neri set within a small niche.[130]

Monos Foundation

Based in a large, Victorian house built from Charnwood Forest stone, just a short distance from the abbey, the Monos Foundation is described as "a Christian organisation that through community and education seeks to foster a monastic spirit within the Church, in all its diversity, and society at large".[131]

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century this house was known as "Charnwood Tower" and was the home of Mrs Emma Frances Haydock, who was a generous benefactor to the Roman Catholic cause locally.[132] Mrs Haydock was of the Worsley Worswick family and was laid to rest in the secular cemetery of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey in 1929.[133] In more recent years, the house has been leased for use as a public house known as The Belfry and as a residential care home known as Abbey Grange.

The house has since been renamed by the Monos Foundation as "The Mercian Centre" and the building is also home to the Saint Joseph Tearoom, which is open to members of the public six days a week.[134]

References

- ↑ http://www.eastlulworth.org.uk/east_lulworth_monastery_farml.html

- 1 2 3 4 Pevsner, Nikolaus et al: "The Buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland", Second Edition, 1984, published by Penguin Books pages 323 - 325

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Mount Saint Bernard Abbey: A Brief Historical Sketch", late 20th-century leaflet by St Bernard Monastery

- 1 2 Young, Victoria M: "A.W.N Pugin's Mount Saint Bernard Abbey: The International Character of England's Nineteenth-Century Monastic Revival".

- ↑ Fletcher, J.M.J: "A Visit to the Monstery of Mount Saint Bernard in Leicestershire: With a Short Account of Monasticism", 1872

- ↑ Lacey, Andrew: "The Second Spring in Charnwood Forest", publd by East Midlands Studies Unit, Loughborough, 1985

- ↑ http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-489626-church-of-st-andrew-leicestershire#.VuSqGWYqW1s

- ↑ "A Concise History of the Cistercian Order: With it's Revival in England at St Susan's, Lullworth and Mount St. Bernard Leicestershire", by "A Cistercian Monk", 1852, p.282-3

- 1 2 Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 1843

- ↑ A Concise History of the Cistercian Order: With it's Revival in England at St Susan's, Lullworth and Mount St. Bernard Leicestershire", by "A Cistercian Monk", 1852, p.282-3

- ↑ http://www.charleyheritage.org.uk/RomanHorde.html

- ↑ C.N.Hadfield, Charnwood Forest, 1952

- ↑ De Selincourt, Ernest: "The Early Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth" 1939, p. 1082.

- ↑ MacCarthy, Fiona: "The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination", Harvard University Press, 2012

- ↑ Burne-Jones 1904, vol. 2, p. 285.

- ↑ Anson, Peter: "Building Up The Waste Places - The Revival of Monastic Life on Medieval Lines in the Post-Reformation Church of England"

- ↑ Nottingham Evening Post, 29 December 1926

- ↑ Weekly Telegraph, 17 May 1919

- ↑ Nottingham Review, 27 February 1846

- ↑ The Catholic Institute Magazine, Vol. II, 1857 - p.131

- ↑ http://www.charleyheritage.org.uk/ResearchingColony.html

- ↑ English Benedictine Congregation History Commission –– Symposium 1982, NINETEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH CISTERCIAN SPIRITUALITY, Dom Hilary Costello

- ↑ Whitwick Community Information

- ↑ http://www.childrenshomes.org.uk/WhitwickRfy/

- ↑ http://www.britishlakes.info/36069-colony-reservoir-leicestershire

- ↑ http://www.charleyheritage.org.uk/ColonyRes.html

- ↑ Havers, Maureen: "The Reformatory at Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, 1856 - 1881", published by Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, 2006.

- ↑ Beeton's Men of The Age and Annals of the Time", publd by Ward, Lock and Tyler, London, 1874

- ↑ Nancy Langham Cooper: "A Brief Biography of J R Herbert", 2013

- ↑ http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/herbert-laborare-est-orare-t01455/text-catalogue-entry

- ↑ Loughborough Advertiser, 29 March 1878

- 1 2 3 Robinson, Albert F: "Holy Cross, Whitwick - A Brief History, 1837 - 1937", published by Whitwick Historical Group, 1987

- 1 2 Obituary, Dom Malachy Brasil (died 1965): http://www.nunraw.com/sanctamaria/dommalachi.htm. Accessed 15.02.16.

- ↑ Fisher, Russell: "Soldiers of Shepshed Remembered, 1914 - 1919", p. 80 (published 2008)

- ↑ The Canadian Register, 17 October 1942

- ↑ "The Private Papers of Hore-Belisha", p.304, published by Collins, 1960

- ↑ http://www.mountsaintbernard.org/7.html

- ↑ Butler, Alban: "Lives of the Saints", Volume 12

- ↑ http://www.eastlulworth.org.uk/past_events.html

- ↑ Reading Eagle/Reading Times, 19 August 2000 (Obituary by Terry Mattingly)

- ↑ The Tablet, 12 August 2000

- ↑ Philip Purser, Guardian newspaper, 5 November 1999

- ↑ Leicester Evening Mail, 17 December 1957

- ↑ https://leicesterforesteast.wordpress.com/local-protest/

- ↑ http://www.stanleyroseman-journal.com/fatherbenedict.html

- ↑ English Heritage listing

- ↑ "Churches in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Nottingham: An Architectural and Historical Review", Architectural History Practice Limited, April 2011

- ↑ Daily Mirror, 3 September 1998

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout (East Midlands), Article: 29 September 2014

- ↑ Leicester Mercury, July 24, 2009.

- ↑ "The Bones of Stratford Langthorne Abbey", CD publication by Charley Heritage Group

- ↑ Leicester Mercury, 21 January 2014

- 1 2 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/106380975

- ↑ "A Concise History of the Cistercian Order: With it's Revival in England at St Susan's, Lullworth and Mount St. Bernard Leicestershire", by "A Cistercian Monk", 1852, p.280. (States that Benedict Johnson died in his 54th year)

- 1 2 https://myancestors.wordpress.com/2008/03/05/john-bernard-palmer-1782-1852/

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography, Elder & Co, 1895, p.143

- 1 2 http://www.zisterzienserlexikon.de/wiki/Burder,_Bernard

- ↑ http://archive.thetablet.co.uk/article/24th-may-1890/9/in-memoriam

- ↑ http://catholicheritage.blogspot.co.uk/2011/06/lords-abbot-of-mount-melleray.html

- ↑ The Catholic Who's Who and Yearbook - Volume 34 (1924) - Page 353

- ↑ http://archive.thetablet.co.uk/article/7th-august-1965/18/dom-malachy-brasil

- ↑ http://www.ocso.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=655%3Adeces-de-dom-ambrose&catid=37%3Ageneral-news&Itemid=77&lang=en

- ↑ http://nunraw.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/news-mount-saint-bernard-abbey.html

- ↑ Potter, T.R: "The History and Antiquities of Charnwood Forest", 1842, p 159

- ↑ http://www.stmarysloughborough.org.uk/about-us/history/

- ↑ Recusant History, Volume 16, page 101

- ↑ Dom Hilary Costello: "Nineteenth Century English Cistercian Spirituality", 1982

- ↑ "A Concise History of the Cistercian Order: With it's Revival in England at St Susan's, Lullworth and Mount St. Bernard Leicestershire", by "A Cistercian Monk", 1852, p.280

- ↑ Recusant History: A journal of research in Post-Reformation Catholic history in the British Isles - Volume 23, Arundel Press, 1996

- 1 2 The Tablet, 10 July 1948

- ↑ Perkins, William Rufus: "History of the Trappist Abbey of New Melleray in Dubuoue County, Iowa",1892.

- ↑ http://www.zisterzienserlexikon.de/wiki/Brasil,_Malachy

- ↑ cl.boutin@ocso.org. "The Death of Dom Ambrose".

- ↑ Holy Cross Abbey, Whitland - website: www.hcawhitland.co.uk

- ↑ Charley Parish Council, Chairman's Report, May 2014

- ↑ Fr Donald. "Dom Donald's Blog: News Mount Saint Bernard Abbey".

- ↑ http://www.zisterzienserlexikon.de/wiki/Mount_Saint_Bernard/%C3%84bteliste

- ↑ http://www.pluscardenabbey.org/newsandevents/2015/10/7/pentecost-lectures-2015

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kym7UbUDdyc

- ↑ http://www.theartsdesk.com/tv/saints-and-sinners-britains-millennium-monasteries-bbc-four

- ↑ http://www.hymntime.com/tch/bio/c/o/l/collins_ha.htm

- ↑ http://www.litpress.org

- ↑ The Tablet, 30 August 1952

- ↑ Financial Times, 11 Jan 2013

- ↑ The Publishers' Circular and Booksellers' Record, 1951.

- ↑ James, Liz: "A Companion to Byzantium", Blackwell Publishing, 2010, p. 285

- ↑ English Benedictine Congregation History Commission –– Symposium 1982, NINETEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH CISTERCIAN SPIRITUALITY, Dom Hilary Costello

- ↑ Independent Catholic News, 9 January 2010

- ↑ http://charley.leicestershireparishcouncils.org/parish-news.html

- ↑ http://nunraw.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/brother-gabriel-manoque-osco-rip-99-yrs.html

- 1 2 3 http://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout/eastmidlands/series7/monastery.shtml

- ↑ Daily Telegraph, 21 February 2016

- ↑ http://www.beeretseq.com/brewing-at-mount-saint-bernard-abbey-in-england-19th-century/

- ↑ http://www.trappist.be/en/pages/trappist-beers

- ↑ 'Every Saturday: A Journal of Choice Reading', Vol II, July to December 1872.

- ↑ Article: 'An English Monastery', published in the Journal, 'All the Year Round', 1890.

- ↑ Memoir of Antwerp, published by John Ollivier, Pall Mall, London, 1847.

- ↑ Latto, Douglas: "The Importance of Vegetarianism to Maintain Perfect Health", The Vegetarian World Forum No. 3 Vol. IX - Autumn 1955 pp.22-28

- ↑ Meninger, William - "1012 Monastery Road: A Spiritual Journey", 2004

- ↑ "Sex, Death and the Meaning of Life - 4oD - Channel 4".

- ↑ "Anglican Cistercians? Who and what are we?". Anglican Cistercians. 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ All information within this section taken from wall mounted guide in the abbey narthex and Pevsner's "Buildings of England (Leicestershire and Rutland)", unless otherwise indicated

- ↑ Purcell, Edmund Sheridan: "Life and Letters of Ambrose Phillips de Lisle", MacMillan, 1900.

- 1 2 3 Birmingham Daily Post, 4 February 1939

- ↑ http://sainttheodores.org/sculpture.htm

- ↑ http://gracedieu.com/history-manor-house/

- ↑ http://nunraw.blogspot.co.uk/2007/10/visiting-mount-saint-bernard-abbey.html

- ↑ Woodward, John: "A Treatise On Ecclesiastical Heraldry", 1894

- ↑ http://www.holycrosschurchwhitwick.org.uk/history/

- ↑ Leicester Chronicle, 22 August 1896

- ↑ http://www.pgatour.com/news/2015/06/02/jack-nicklaus-statues.html. Accessed 11.05.16

- ↑ Heritage Lottery Fund, Schedule of Decisions, 20.02.13

- ↑ http://nunraw.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/mark-hartley-cistercian.html

- ↑ http://www.stmarysgrantham.org.uk (PDF)

- ↑ http://www.newarktownhallmuseum.co.uk/robert-kiddey.html

- ↑ Albert Herbert FRIBA FSA 1875-1964 (PDF Document) https://www.le.ac.uk/lahs/downloads/ObitSmPagesfromvolumeXL-4.pdf - accessed 20.07.16

- ↑ http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ccaajpa/1and2.html

- ↑ http://www.warksbells.co.uk/

- ↑ http://www.leicestershirewarmemorials.co.uk/war/memorials/view/1249

- ↑ Nottingham Evening Post, 16.06.1882

- ↑ http://web.onetel.com/~pelhamwest/pelham/P8-Pound.htm

- ↑ "A Concise History of the Cistercian Order: With it's Revival in England at St Susan's, Lullworth and Mount St. Bernard Leicestershire", by "A Cistercian Monk", 1852, p.293

- ↑ The Mercury (Hobart), 10 October 1904

- ↑ http://www.stjosephsbedford.org/a-visit-to-mount-st-bernard-abbey/

- ↑ Roderick O'Donnell: "The Pugins and The Catholic Midlands", 2002

- ↑ William White: "History, Gazetteer and Directory of Leicestershire", 1846

- ↑ Thringstone Village Trail, No 3 - The Warren and Cademan Woods, Friends of Thringstone local history publication

- 1 2 http://www.thepuginsociety.co.uk/miscellaneous.html

- ↑ https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1074163

- ↑ http://www.charleyheritage.org.uk/AbbeyLodge.html

- ↑ http://www.monos.org.uk/Monos-Welcome

- ↑ The Tablet, 24 April 1920

- ↑ Barrow Upon Soar Heritage Group: website, accessed 09.11.16

- ↑ http://www.merciancentre.co.uk/MercianCentre-Welcome

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mount St Bernard Abbey. |