Moses Shapira

Moses Wilhelm Shapira (Hebrew: מוזס וילהלם שפירא; 1830 – March 9, 1884) was a Jerusalem antiquities dealer and purveyor of allegedly forged Biblical artifacts.[1][2] The shame brought about by accusations that he was involved in the forging of ancient biblical texts drove him to suicide in 1884. The discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls in 1947, in approximately the same area he claimed his material was discovered, has cast some doubt on the original forgery charges.[1][2]

Early life and career

Moses Wilhelm Shapira was born in 1830 to Polish-Jewish parents in Kamenets-Podolski, which at the time was part of Russian-annexed Poland (in modern-day Ukraine). Shapira's father emigrated to Ottoman Palestine and in 1856, at the age of 25, Moses Shapira followed. His grandfather, who accompanied him, died en route.

On the way, while in Bucharest, Moses Shapira converted to Christianity and applied for German citizenship. Once in Jerusalem, he joined the community of Anglican missionaries and converts[3] and in 1861 opened a store[4] in the Street of the Christians, today's Christian Quarter Road. He sold the usual religious souvenirs enjoyed by pilgrims, as well as ancient pots he acquired from Arab farmers.

Moabite forgeries

Shapira became interested in biblical artifacts after the appearance of the so-called Moabite Stone, also known as the Mesha Stele. He witnessed the huge interest around it and may have had a hand in negotiating on behalf of the German representatives. France eventually got the fragments of the original stone, leaving the British and the Germans rather frustrated.

The squeeze which helped reconstruct the shattered Mesha Stele was taken on behalf of the French scholar and diplomat Charles Clermont-Ganneau by a Christian Arab painter and dragoman (tour-guide), Salim al-Khouri, better known as Salim al-Kari, "the reader", a nickname apparently given to him by the Bedouin due to his work with ancient alphabets. Salim soon became Shapira's associate and provided connections to Arab craftsmen who, along with Salim himself, produced for Shapira's shop large amounts of fake Moabite artifacts – large stone-made human heads, but mainly clay objects: vessels, figurines and erotic pieces, generously covered with inscriptions based chiefly on the signs Salim had copied from the Mesha Stele. To modern scholars, the products seem clumsy – inscriptions do not translate to anything legible, for one – but at the time there was little with which to compare them. Shapira even organized an expedition to Moab for potential buyers, to sites where he had Salim's Bedouin associates bury more forgeries. Some scholars began to base theories on these pieces and the term Moabitica was coined for this entirely new category of "Moabite" artifacts.

Since German archaeologists had not gained possession of the Moabite Stone, they rushed to buy the Shapira Collection ahead of their rivals. Berlin's Altes Museum bought 1700 artifacts for the cost of 22,000 thalers in 1873. Other private collectors followed suit. One of them was Horatio Kitchener, a not yet famous British lieutenant, who bought eight pieces for the Palestine Exploration Fund. Shapira was able to move to the luxurious Aga Rashid property (modern-day Ticho House), outside Jerusalem's squalid Old City, with his wife and two daughters.

Still various people, including Charles Clermont-Ganneau, had their doubts. Clermont-Ganneau suspected Salim al-Kari, questioned him and in time found the man who supplied him with clay, a stonemason who worked for him, and other accomplices. He published his findings in Athenaeum newspaper in London and declared all "Moabitica" to be forgeries, a conclusion with which even the German scholars eventually concurred (cf. Emil Friedrich Kautzsch and Albert Socin, Die Echtheit der moabitischen Altertümer geprüft, 1876). Shapira defended his collection vigorously until his rivals presented more evidence against them. He placed the entire blame on Salim al-Kari, convinced almost everyone to be just an innocent victim, and continued to do a considerable trade especially in genuine old Hebrew manuscripts from Yemen.

Manuscript forgeries

In 1883 Shapira presented what is now known as the Shapira Strips, a supposedly ancient scroll written on leather strips which he claimed had been found near the Dead Sea. The Hebrew text hinted at a different version of Deuteronomy, including a surprising eleventh commandment ("Thou shalt not hate thy brother in thy heart: I am God, thy God"). Shapira sought to sell them to the British Museum for a million pounds, and allowed them to exhibit two of the 15 strips. The exhibition was attended by thousands.

However, Clermont-Ganneau also attended the exhibition; Shapira had denied him access to the other 13 strips. After close examination, Clermont-Ganneau declared them to be forgeries. Soon afterward British biblical scholar Christian David Ginsburg came to the same conclusion. Later Clermont-Ganneau showed that the leather of the Deuteronomy scroll was quite possibly cut from the margin of a genuine Yemenite scroll that Shapira had previously sold to the Museum.

Shapira fled London in despair, his name ruined and all of his hopes crashed. Six months later, on March 9, 1884 he shot himself in Hotel Bloemendaal in Rotterdam.

The Shapira Strips disappeared and then reappeared a couple of years later in a Sotheby's auction, where they were sold for 10 guineas. In 1899 they were probably destroyed in a fire at the house of the presumed final owner, Sir Charles Nicholson.

No new final evidence

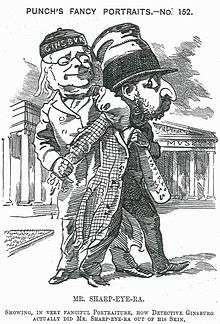

Despite the assessment of contemporary scholars - German ones from Halle, Leipzig and Berlin, Clermont-Ganneau from France, Christian David Ginsburg of London - declaring with good arguments either that the leather had only been recently processed, or that the Hebrew script and language used were flawed, and even leaving aside the fact that the peculiar "eleventh commandment" showed Christian leanings which could be connected to Shapira's own conversion, there have always been researchers claiming to have reasons to believe that the Deuteronomy scroll might be a genuine ancient artifact after all. The presumed but hard to prove physical loss of the strips in the 1899 fire leaves space for speculation, but none for actual research.[5] There are no major scholars dealing with the issue currently, especially since nobody has produced any surviving fragment of the strips, the only useful facsimile being the well-known one created by Ginsburg back in 1883. Fact is also that contemporary press articles which ridiculed Shapira using despicable anti-Semitic stereotypes did not precede, but rather followed the rejection of the scroll by a large range of scholars.[6][7][8]

Heritage

Shapira "Moabitica" fakes still exist in museums and private collections around the world but are rarely displayed. By now they have become desirable collectibles in their own right.

The exact location of Shapira's shop on Christian Quarter Road in Jerusalem has now been identified.[9]

References

- 1 2 Allegro, John Marco (1965). The Shapira affair. Doubleday.

- 1 2 Vermès, Géza (2010). The story of the scrolls: the miraculous discovery and true significance of the Dead Sea scrolls. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-104615-0.

- ↑ Singer, Isidore; Joseph Jacobs. "SHAPIRA, M. W.". Jewish Encyclopedia. pp. 232–233.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Unsigned (1911). "Shapira, M. W.". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 803.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Unsigned (1911). "Shapira, M. W.". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 803. - ↑ James R. Davila, PhD, Professor of Early Jewish Studies (2013-11-03). "The Shapira forgeries raise their moldering heads again". Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ Oskar K. Rabinowicz (July 1965). "The Shapira Scroll: An nineteenth-century forgery". The Jewish Quarterly Review: New Series. University of Pennsylvania Press. 56 (1): 1–21. JSTOR 1453329.

- ↑ "Mr. Sharp-Eye-Ra (cartoon)". Punch (magazine). September 1883. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ Press, Michael (July 1214). ""The Lying Pen of the Scribes": A Nineteenth-Century Dead Sea Scroll". The Appendix. 2 (3). Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- ↑ Guil, Shlomo (June 2012). "In the Footsteps of the Concealed Shop". Et Mol. 223.

Further reading

- E. F. Kautzsch and A. Socin, Die Echtheit der moabitischen Altertümer geprüft (1876)

- "Faking it" - Radio piece on Shapira produced by Israel story podcast for Tablet Magazine , 18 August 2014.

- Tigay, Chanan, The Lost Book of Moses (2016) ISBN 0062206419