Henry Morton Stanley's first trans-Africa exploration

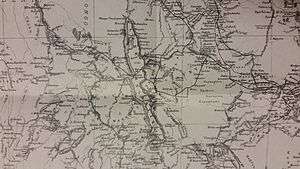

Between 1874 and 1877 Henry Morton Stanley traveled central Africa East to West, exploring Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika and the Lualaba and Congo rivers.[1] He covered 7,000 miles (11,000 km) from Zanzibar in the east to Boma in the mouth of the Congo in the west and resolved a number of open questions concerning the geography of central Africa. This including identifying the source of the Nile, which he proved was not the Lualaba - which is in fact the source of the river Congo.

Previous African Journey

This was Stanley's second journey in central Africa. In 1871–1872 he had searched for and successfully found the missionary and explorer Livingstone, greeting him with the famous (though disputed) words: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”.[2][3]

Objectives

Stanley's journey had four principal aims,[4] to:

- Explore Lake Victoria and its inflowing and outflowing rivers

- Explore Lake Albert and its inflowing and outflowing rivers

- Explore Lake Tanganyika, checking the direction of flow of the river Rusizi at the north end of the lake

- Explore the Lualaba River downstream towards its outflow

There was controversy among earlier explorers as to whether these lakes and rivers were connected to each other and the Nile. Richard Burton thought that Lake Victoria might have a southern inlet, possibly from Lake Albert, meaning that the source of the Nile was not Lake Victoria as Speke had argued. Samuel Baker thought that Lake Albert might have an inlet from Lake Tanganyika. Livingstone thought that Lualaba was the source of the Nile.

Being sponsored by the New York Herald - at the instigation of its then editor, James Gordon Bennett Jr.,[5] - and the Daily Telegraph newspapers, Stanley he was expected to write dispatches for them. He subsequently wrote a book of his experiences, Through the Dark Continent.

Preparations

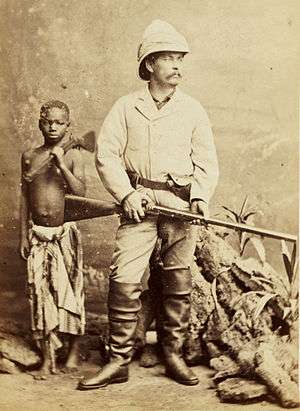

On September 21, 1874 Stanley arrived Zanzibar. He took with him three young Englishmen, Frederick Barker and the brothers Francis and Edward Pocock, and Kalulu, an African he had taken to England on his earlier trip and who was educated briefly in England. He also took 60 pounds of cloth, copper wire and beads (Sami Sami) for trading, a barometer, watches and chronometers, sextant, compasses, photographic equipment, Snider rifles and elephant gun(s), and the parts of a 40 ft boat with single sail, named Lady Alice after his fiancee. In Zanzibar he recruited African porters to a total of 230 people, including 36 women and 10 boys. He recruited mainly from the Wangwana, Wanyamwezi and coast people from Mombasa.[6]:3–4,22,51,65

On November 12, 1874 he left in Zanzibar for the mainland.[7] Five days later he left from Bagamoyo. After fighting with Wanyaturu, they reached Lake Victoria on 27 February, having traveled 720 miles (1,160 km) in 103 days.[6]:54,101,115,92 62 members of the party died en route, including Edward Pocock.

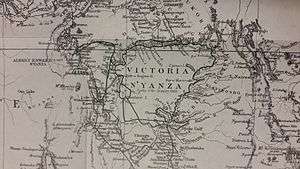

Circumnavigation of Lake Victoria

On March 8, 1875,[8] Stanley, with ten sailors and a steersman, left his camp site near Kageghi in the Lady Alice. They explored and named Speke Bay, after the first European to see the Lake. They also discovered the main river Simiyu River inlet in the South. Passing Ukerewe Island, he was attacked by Wavuma people in canoes, but escaped after firing at his attackers.[6]:123,126,141–142

On April 4 he landed on the northern bank near the Ripon Falls, the only outlet of the lake, which had been identified as the source of the Nile by Speke. He was received as a royal guest by Mutesa I of Buganda. Stanley wrote that Buganda would be an ideal country to establish missions, and for European trade.[6]:142–165

Stanley's party left on April 21, heading southward. First they reached the inlet of the Kagera river, which they would later explore on their way to Lake Albert. In an attempt to get supplies of food, they landed on the island of Bumbireh. The local inhabitants alternated peace talks with thefts and threats, and stole their canoe paddles. Ultimately the crew escaped, killing some locals in the process.[6]:167–186 Later Stanley would write he killed 10 (and elsewhere 14) in his dispatches to newspapers. This would later be used to traduce his character as a ruthless killer. Why he mis-stated the number of deaths is not clear; his biographer Tim Jeal has tried to clarify.[9]

On May 5, the party arrived back in Kagehyi and rejoined the main group. In the meantime Barker had died of disease, as had Mabuki Speke (who was on earlier travels with Livingstone, Speke, Grant and Burton). Stanley had spent 57 days exploring Lake Victoria.[6]:188–191 His detailed measurements and descriptions led to a major revision of its geography. He established that the Kagera River was its main inflow, and that it was 4,093 feet (1,248 m) above sea level, with a maximum depth of 275 feet (84 m).

Lake Albert

Stanley intended to explore Lake Albert next.[10] However, war between Uganda and Wavuma forced him either to "renounce the project of exploring the Albert, and proceed at once to the Tanganika...or to wait patiently until the war was over." After the war ended with an Ugandan victory, however, his expedition was thwarted by Kabarega, king of the Unyoro.[6]:233,238,346,349,

Lake Tanganyika

On May 27, 1876 the party arrived in Ujiji on the shore of Lake Tanganyika, the village where Stanley had famously met Livingstone a few years before.[11][6]:399 Their objective was to survey the lake, seeking inlets and outlets. By July 31 the 930 miles (1,500 km) of the lake perimeter was charted. Its main outlet was found to be the Lukuga River on the western shore. The depth of the lake was measured to be in excess of 1,280 feet (390 m).[6]:Vol. Two:40,47

Rivers Lualaba and Congo

The final objective was to determine whether the Lualaba river fed the Nile (Livingstone's theory), the Congo[12] or even the Niger. On August 25, 1876 Stanley left Ujiji with an expedition of 132, crossing the lake westward to Manyema,[6]:Vol. Two:50 to enter the heart of Africa. In October they reached the confluence of the Luama River and the Lualaba River. Entering Manyema, they were now in a lawless area containing cannibal tribes. Tippu Tip based his source of slaves here. Also, Livingstone had witnessed a massacre of Africans here, and did not succeed in getting any further. Nor had Vernon Cameron in 1874. However Stanley reached a contract with Tippu Tip, in which they agreed to accompany each other for "sixty marches-each march of four hours' duration". They reached Nyangwe on 28 Oct.[6]:Vol. 68,74–97

The party left Nyangwe overland and entered the dense Matimba forest on 6 Nov. On November 19 they reached the Lualaba again where Stanley proceeded downstream with the Lady Alice, and Tippu Tip kept pace on the eastern shore. They traversed through the lands of the cannibal Wenya. Though he attempted to negotiate a peaceful thoroughfare, the tribes were wary as their only experience of outsiders was of slave traders. They reached Kindu on 5 Dec. 1876, but it wasn't until they reached Vinya-Njara, that Stanley could conclude a "blood-brotherhood" with the natives and peace ensued. Tippu Tip left Stanley at this point, while Stanley departed downstream on 28 December with 149 men, women and children on 23 canoes.[6]:101–152

On January 6, 1877, after 400 miles (640 km), they reached Boyoma Falls (called Stanley Falls for some time after), consisting of seven cataracts spanning 60 miles (97 km), and the confluence of the Lomami River. It took them until 28 Jan. to reach the end of the Falls, sometimes passing overland, and always having to defend themselves from attacks by the cannibal natives.[6]:175–199

Stanley reached the confluence of the Aruwimi River on 1 Feb., and then the land of the Bemberri cannibals. Finally at the village of Rubunga, they were able to enter into a blood-brotherhood with the natives. Here Stanley learned that the river was called Ikuta ya Kongo,[13] proving to him that he had reached the Congo, and that the Lualaba did not feed the Nile.[6]:209–221

Stanley was then attacked by the Urangi and then the Marunja, both of whom possessed Portuguese muskets. His thirty-first fight along the river was with the Bangala on 14 Feb., facing 63 canoes and 315 muskets. On 18 Feb. they reached the confluence of the Ikelemba River and were able to trade at Ikengo. The 26 Feb. found them at Bolobo, where they were welcomed by the king of Chumbiri. They reached the confluence of the Lefini River and the Kasai River with the Congo on 9 March. This was the location of their thirty-second and last fight.[6]:226–227,232,234–235,238–240,244–246,251–252

On 12 March, they reached Stanley Pool (now Pool Malebo). Here Stanley met with Mankoneh, the Bateke chief and Itsi, chief of the Ntamo, forming a blood-brotherhood.[6]:254–259 This is the site of the present day cities Kinshasa and Brazzaville, capitals of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo.

Further downstream were the Livingstone Falls, 1235 miles downstream from Nyangwe, a series of 32 falls and rapids with a fall of 1,100 feet (340 m) over 155 miles (249 km).[6]:259–261 On March 16 they started the descent of the falls, which cost numerous lives, including those of Frank Pocock and Kalulu, his England-educated servant.[6]:261,265,315

On 30 July, Stanley stated, "We drew our boat and canoes into a sandy-edged basin in the low rocky terrace, and proceeded to view the cataract of Isangila." Only five days journey from Ebomma, Stanley stated, "I saw no reason to follow it farther, or to expend the little remaining vitality we possessed in toiling through the last four cataracts."[6]:340–341

On August 3 they reached the village of Nsanda. From there Stanley sent forward four trusted men to Boma with letters in English, French and Spanish, asking them to send food for his starving people. On August 6 relief came, being sent by representatives from the Liverpool trading firm Hatton & Cookson. August 9 they reached Boma, 999 days since leaving Zanzibar on November 12, 1874. The party then consisted of 115 people, including three children born during the trip.[6]:345–359

Most probably (Stanley's own publications give inconsistent figures), he lost 132 people through disease, hunger, drowning, killing and desertion. Some 18 deserted, an extremely low figure given the dangers of the country they had crossed.[14]

Return

In Boma he mailed his editor Bennett in New York to send money for his party and arrange homeward travel. He also learned through his publisher that his fiancee Alice had married a Mr Barney, owner of America's biggest rolling stock producer.

They left Boma for Kabinda, arriving 12 Aug. Eventually the party went to Luanda (Angola), arriving on 28 Sept. From there to Simon's Town on 21 Oct., and finally Zanzibar, via the HMS Industry, arriving November 26. On 13 Dec., Stanley left Zanzibar on the S.S. Pachumba for home, being carried on his men's shoulders to the longboat ferrying him to the ship.[6]:362,365–366,368,372

In articles about his discoveries he urged Western powers to organise trade with central Africa and reduce the slave trade in the interior. Stanley's book Through the Dark Continent, describing his journey, was published in 1878 and was a great success.

References

- Bibliography

- Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22102-8.

- Stanley, Henry Morton (1878). Through the Dark Continent.

- The Exploration Diaries of H.M. Stanley. Richard Stanley Richard, Alan Neame, eds. 1961.

- Notes

- ↑ Jeal 2007, p. 157-219 passim.

- ↑ Jeal 2007, p. 117-120.

- ↑ "Stanley, Sir Henry Morton". Winkler Prins (in Dutch). 17. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 1973.

would have said (nl: zou hebben geuit)

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 164.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 157-164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Stanley, H.M., 1899, Through the Dark Continent, London: G. Newnes, Vol. One ISBN 0486256677, Vol. Two ISBN 0486256685

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 164-170.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 171-183.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 178.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 180-184.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 185-187.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 188-219.

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 199; February 7, 1877

- ↑ Jeal, 2007 p. 217.