Mitosis

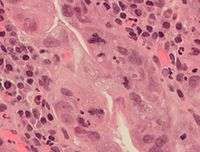

a. non-dividing cells

b. nuclei preparing for division (spireme-stage)

c. dividing cells showing mitotic figures

e. pair of daughter-cells shortly after division

In cell biology, mitosis is a part of the cell cycle when replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. In general, mitosis (division of the nucleus) is preceded by the S stage of interphase (during which the DNA is replicated) and is often accompanied or followed by cytokinesis, which divides the cytoplasm, organelles and cell membrane into two new cells containing roughly equal shares of these cellular components.[1] Mitosis and cytokinesis together define the mitotic (M) phase of an animal cell cycle—the division of the mother cell into two daughter cells genetically identical to each other.

The process of mitosis is divided into stages corresponding to the completion of one set of activities and the start of the next. These stages are prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. During mitosis, the chromosomes, which have already duplicated, condense and attach to spindle fibers that pull one copy of each chromosome to opposite sides of the cell.[2] The result is two genetically identical daughter nuclei. The rest of the cell may then continue to divide by cytokinesis to produce two daughter cells.[3] Producing three or more daughter cells instead of normal two is a mitotic error called tripolar mitosis or multipolar mitosis (direct cell triplication / multiplication).[4] Other errors during mitosis can induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) or cause mutations. Certain types of cancer can arise from such mutations.[5]

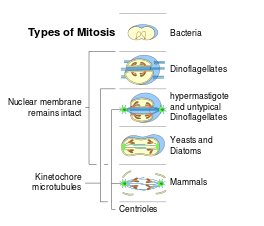

Mitosis occurs only in eukaryotic cells and the process varies in different organisms.[6] For example, animals undergo an "open" mitosis, where the nuclear envelope breaks down before the chromosomes separate, while fungi undergo a "closed" mitosis, where chromosomes divide within an intact cell nucleus.[7] Furthermore, most animal cells undergo a shape change, known as mitotic cell rounding, to adopt a near spherical morphology at the start of mitosis. Prokaryotic cells, which lack a nucleus, divide by a different process called binary fission.

Discovery

German zoologist Otto Bütschli might have claimed the discovery of the process presently known as "mitosis",[8] a term coined by Walther Flemming in 1882.[9]

Mitosis was discovered in frog, rabbit, and cat cornea cells in 1873 and described for the first time by the Polish histologist Wacław Mayzel in 1875.[10][11] The term is derived from the Greek word μίτος mitos "warp thread".[12][13]

Overview of mitosis

The primary result of mitosis and cytokinesis is the transfer of a parent cell's genome into two daughter cells. The genome is composed of a number of chromosomes—complexes of tightly coiled DNA that contain genetic information vital for proper cell function. Because each resultant daughter cell should be genetically identical to the parent cell, the parent cell must make a copy of each chromosome before mitosis. This occurs during the S phase of interphase.[14] Chromosome duplication results in two identical sister chromatids bound together by cohesin proteins at the centromere.

When mitosis begins, the chromosomes condense and become visible. In some eukaryotes, for example animals, the nuclear envelope, which segregates the DNA from the cytoplasm, disintegrates into small vesicles. The nucleolus, which makes ribosomes in the cell, also disappears. Microtubules project from opposite ends of the cell, attach to the centromeres, and align the chromosomes centrally within the cell. The microtubules then contract to pull the sister chromatids of each chromosome apart.[15] Sister chromatids at this point are called daughter chromosomes. As the cell elongates, corresponding daughter chromosomes are pulled toward opposite ends of the cell and condense maximally in late anaphase. A new nuclear envelope forms around the separated daughter chromosomes, which decondense to form interphase nuclei.

During mitotic progression, typically after anaphase onset, the cell may undergo cytokinesis. In animal cells, a cell membrane pinches inward between the two developing nuclei to produce two new cells. In plant cells, a cell plate forms between the two nuclei. Cytokinesis does not always occur; coenocytic (a type of multinucleate condition) cells undergo mitosis without cytokinesis.

Phases of cell cycle and mitosis

Interphase

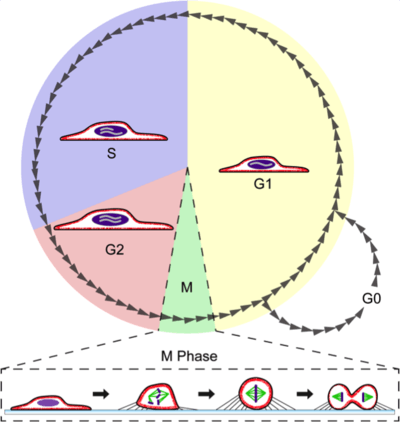

The mitotic phase is a relatively short period of the cell cycle. It alternates with the much longer interphase, where the cell prepares itself for the process of cell division. Interphase is divided into three phases: G1 (first gap), S (synthesis), and G2 (second gap). During all three phases, the cell grows by producing proteins and cytoplasmic organelles. However, chromosomes are replicated only during the S phase. Thus, a cell grows (G1), continues to grow as it duplicates its chromosomes (S), grows more and prepares for mitosis (G2), and finally divides (M) before restarting the cycle.[14] All these phases in the cell cycle are highly regulated by cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, and other cell cycle proteins. The phases follow one another in strict order and there are "checkpoints" that give the cell cues to proceed from one phase to another. Cells may also temporarily or permanently leave the cell cycle and enter G0 phase to stop dividing. This can occur when cells become overcrowded (density-dependent inhibition) or when they differentiate to carry out specific functions for the organism, as is the case for human heart muscle cells and neurons. Some G0 cells have the ability to re-enter the cell cycle.

Preprophase (plant cells)

In plant cells only, prophase is preceded by a pre-prophase stage. In highly vacuolated plant cells, the nucleus has to migrate into the center of the cell before mitosis can begin. This is achieved through the formation of a phragmosome, a transverse sheet of cytoplasm that bisects the cell along the future plane of cell division. In addition to phragmosome formation, preprophase is characterized by the formation of a ring of microtubules and actin filaments (called preprophase band) underneath the plasma membrane around the equatorial plane of the future mitotic spindle. This band marks the position where the cell will eventually divide. The cells of higher plants (such as the flowering plants) lack centrioles; instead, microtubules form a spindle on the surface of the nucleus and are then organized into a spindle by the chromosomes themselves, after the nuclear envelope breaks down.[16] The preprophase band disappears during nuclear envelope breakdown and spindle formation in prometaphase.[17]

Prophase

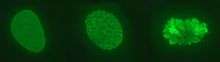

During prophase, which occurs after G2 interphase, the cell prepares to divide by tightly condensing its chromosomes and initiating mitotic spindle formation, this process is called chromosome condensation. During interphase, the genetic material in the nucleus consists of loosely packed chromatin. At the onset of prophase, chromatin fibers condense into discrete chromosomes that are typically visible at high magnification through a light microscope. In this stage, chromosomes are long, thin and thread-like. Each chromosome has two chromatids. The two chromatids are joined at a place called centromere.

Gene transcription ceases during prophase and does not resume until late anaphase to early G1 phase.[18][19][20] The nucleolus also disappears during early prophase.[21]

Close to the nucleus of animal cells are structures called centrosomes, consisting of a pair of centrioles surrounded by a loose collection of proteins. The centrosome is the coordinating center for the cell's microtubules. A cell inherits a single centrosome at cell division, which is duplicated by the cell before a new round of mitosis begins, giving a pair of centrosomes. The two centrosomes polymerize tubulin to help form a microtubule spindle apparatus. Motor proteins then push the centrosomes along these microtubules to opposite sides of the cell. Although centrosomes help organize microtubule assembly, they are not essential for the formation of the spindle apparatus, since they are absent from plants,[16] and are not absolutely required for animal cell mitosis.[22]

Prometaphase

At the beginning of prometaphase in animal cells, phosphorylation of nuclear lamins causes the nuclear envelope to disintegrate into small membrane vesicles. As this happens, microtubules invade the nuclear space. This is called open mitosis, and it occurs in some multicellular organisms. Fungi and some protists, such as algae or trichomonads, undergo a variation called closed mitosis where the spindle forms inside the nucleus, or the microtubules penetrate the intact nuclear envelope.[23][24]

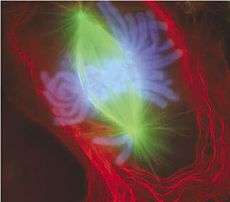

In late prometaphase, kinetochore microtubules begin to search for and attach to chromosomal kinetochores.[25] A kinetochore is a proteinaceous microtubule-binding structure that forms on the chromosomal centromere during late prophase.[25][26] A number of polar microtubules find and interact with corresponding polar microtubules from the opposite centrosome to form the mitotic spindle.[27] Although the kinetochore structure and function are not fully understood, it is known that it contains some form of molecular motor.[28] When a microtubule connects with the kinetochore, the motor activates, using energy from ATP to "crawl" up the tube toward the originating centrosome. This motor activity, coupled with polymerisation and depolymerisation of microtubules, provides the pulling force necessary to later separate the chromosome's two chromatids.[28]

Metaphase

After the microtubules have located and attached to the kinetochores in prometaphase, the two centrosomes begin pulling the chromosomes towards opposite ends of the cell. The resulting tension causes the chromosomes to align along the metaphase plate or equatorial plane, an imaginary line that is centrally located between the two centrosomes (at approximately the midline of the cell).[27] To ensure equitable distribution of chromosomes at the end of mitosis, the metaphase checkpoint guarantees that kinetochores are properly attached to the mitotic spindle and that the chromosomes are aligned along the metaphase plate.[29] If the cell successfully passes through the metaphase checkpoint, it proceeds to anaphase.

Anaphase

During anaphase A, the cohesins that bind sister chromatids together are cleaved, forming two identical daughter chromosomes.[30] Shortening of the kinetochore microtubules pulls the newly formed daughter chromosomes to opposite ends of the cell. During anaphase B, polar microtubules push against each other, causing the cell to elongate.[31] In late anaphase, chromosomes also reach their overall maximal condensation level, to help chromosome segregation and the re-formation of the nucleus.[32] In most animal cells, anaphase A precedes anaphase B, but some vertebrate egg cells demonstrate the opposite order of events.[30]

Telophase

Telophase (from the Greek word τελος meaning "end") is a reversal of prophase and prometaphase events. At telophase, the polar microtubules continue to lengthen, elongating the cell even more. If the nuclear envelope has broken down, a new nuclear envelope forms using the membrane vesicles of the parent cell's old nuclear envelope. The new envelope forms around each set of separated daughter chromosomes (though the membrane does not enclose the centrosomes) and the nucleolus reappears. Both sets of chromosomes, now surrounded by new nuclear membrane, begin to "relax" or decondense. Mitosis is complete. Each daughter nucleus has an identical set of chromosomes. Cell division may or may not occur at this time depending on the organism.

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is not a phase of mitosis but rather a separate process, necessary for completing cell division. In animal cells, a cleavage furrow (pinch) containing a contractile ring develops where the metaphase plate used to be, pinching off the separated nuclei.[33] In both animal and plant cells, cell division is also driven by vesicles derived from the Golgi apparatus, which move along microtubules to the middle of the cell.[34] In plants, this structure coalesces into a cell plate at the center of the phragmoplast and develops into a cell wall, separating the two nuclei. The phragmoplast is a microtubule structure typical for higher plants, whereas some green algae use a phycoplast microtubule array during cytokinesis.[35] Each daughter cell has a complete copy of the genome of its parent cell. The end of cytokinesis marks the end of the M-phase.

There are many cells where mitosis and cytokinesis occur separately, forming single cells with multiple nuclei. The most notable occurrence of this is among the fungi, slime molds, and coenocytic algae, but the phenomenon is found in various other organisms. Even in animals, cytokinesis and mitosis may occur independently, for instance during certain stages of fruit fly embryonic development.[36]

Significance

Mitosis is important for the maintenance of the chromosomal set; each cell formed receives chromosomes that are alike in composition and equal in number to the chromosomes of the parent cell.

Mitosis occurs in the following circumstances:

- Development and growth

- The number of cells within an organism increases by mitosis. This is the basis of the development of a multicellular body from a single cell, i.e., zygote and also the basis of the growth of a multicellular body.

- Cell replacement

- In some parts of body, e.g. skin and digestive tract, cells are constantly sloughed off and replaced by new ones. New cells are formed by mitosis and so are exact copies of the cells being replaced. In like manner, red blood cells have short lifespan (only about 4 months) and new RBCs are formed by mitosis.

- Regeneration

- Some organisms can regenerate body parts. The production of new cells in such instances is achieved by mitosis. For example, starfish regenerate lost arms through mitosis.

- Asexual reproduction

- Some organisms produce genetically similar offspring through asexual reproduction. For example, the hydra reproduces asexually by budding. The cells at the surface of hydra undergo mitosis and form a mass called a bud. Mitosis continues in the cells of the bud and this grows into a new individual. The same division happens during asexual reproduction or vegetative propagation in plants.

Cell shape changes during mitosis

In animal tissue, most cells round up to a near-spherical shape during mitosis.[37][38][39] In epithelia and epidermis, an efficient rounding process is correlated with proper mitotic spindle alignment and subsequent correct positioning of daughter cells.[38][39][40][41] Moreover, researchers have found that if rounding is heavily suppressed it may result in spindle defects, primarily pole splitting and failure to efficiently capture chromosomes.[42] Therefore, mitotic cell rounding is thought to play a protective role in ensuring accurate mitosis.[41][43]

Rounding forces are driven by reorganization of F-actin and myosin (actomyosin) into a contractile homogeneous cell cortex that 1) rigidifies the cell periphery[43][44][45] and 2) facilitates generation of intracellular hydrostatic pressure (up to 10 fold higher than interphase).[46][47][48] The generation of intracellular pressure is particularly critical under confinement, such as would be important in a tissue scenario, where outward forces must be produced to round up against surrounding cells and/or the extracellular matrix. Generation of pressure is dependent on formin-mediated F-actin nucleation[48] and Rho kinase (ROCK)-mediated myosin II contraction,[44][46][48] both of which are governed upstream by signaling pathways RhoA and ECT2[44][45] through the activity of Cdk1.[48] Due to its importance in mitosis, the molecular components and dynamics of the mitotic actomyosin cortex is an area of active research.

Errors and variations of mitosis

Errors can occur during mitosis, especially during early embryonic development in humans.[49] Mitotic errors can create aneuploid cells that have too few or too many of one or more chromosomes, a condition associated with cancer.[50] Early human embryos, cancer cells, infected or intoxicated cells can also suffer from pathological division into three or more daughter cells (tripolar or multipolar mitosis), resulting in severe errors in their chromosomal complements.[4]

In nondisjunction, sister chromatids fail to separate during anaphase.[51] One daughter cell receives both sister chromatids from the nondisjoining chromosome and the other cell receives none. As a result, the former cell gets three copies of the chromosome, a condition known as trisomy, and the latter will have only one copy, a condition known as monosomy. On occasion, when cells experience nondisjunction, they fail to complete cytokinesis and retain both nuclei in one cell, resulting in binucleated cells.[52]

Anaphase lag occurs when the movement of one chromatid is impeded during anaphase.[51] This may be caused by a failure of the mitotic spindle to properly attach to the chromosome. The lagging chromatid is excluded from both nuclei and is lost. Therefore, one of the daughter cells will be monosomic for that chromosome.

Endoreduplication (or endoreplication) occurs when chromosomes duplicate but the cell does not subsequently divide. This results in polyploid cells or, if the chromosomes duplicates repeatedly, polytene chromosomes.[51][53] Endoreduplication is found in many species and appears to be a normal part of development.[53] Endomitosis is a variant of endoreduplication in which cells replicate their chromosomes during S phase and enter, but prematurely terminate, mitosis. Instead of being divided into two new daughter nuclei, the replicated chromosomes are retained within the original nucleus.[36][54] The cells then re-enter G1 and S phase and replicate their chromosomes again.[54] This may occur multiple times, increasing the chromosome number with each round of replication and endomitosis. Platelet-producing megakaryocytes go through endomitosis during cell differentiation.[55][56]

Timeline in pictures

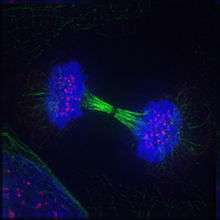

Mitotic cells can be visualized microscopically by staining them with fluorescent antibodies and dyes.

|

See also

- Aneuploidy

- Binary fission

- Chromosome abnormality

- Cytoskeleton

- Meiosis

- Mitogen

- Mitosis Promoting Factor

- Mitotic bookmarking

- Motor protein

References

- ↑ Carter, J. Stein (2014-01-14). "Mitosis". biology.clc.uc.edu.

- ↑ "Cell Division: Stages of Mitosis | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Maton, A.; Hopkins, J. J.; LaHart, S; Quon Warner, D.; Wright, M.; Jill, D. (1997). Cells: Building Blocks of Life. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 70–4. ISBN 0-13-423476-6.

- 1 2 Kalatova, B.; Jesenska, R.; Hlinka, D.; Dudas, M. (2015). "Tripolar mitosis in human cells and embryos: Occurrence, pathophysiology and medical implications". Acta Histochemica. 117 (1): 111–125. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2014.11.009. PMID 25554607.

- ↑ Kops, G. J.; Weaver, B. A.; Cleveland, D. W. (October 2005). "On the road to cancer: Aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint". Nature Reviews Cancer. 5 (10): 773–785. doi:10.1038/nrc1714. PMID 16195750.

- ↑ Raikov, IB (1994). "The diversity of forms of mitosis in protozoa: A comparative review". European Journal of Protistology. 30 (3): 253–69. doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80072-6.

- ↑ De Souza, C. P.; Osmani, S. A. (2007). "Mitosis, Not Just Open or Closed". Eukaryotic Cell. 6 (9): 1521–7. doi:10.1128/EC.00178-07. PMC 2043359

. PMID 17660363.

. PMID 17660363. - ↑ Fokin, S. I. (2013). "Otto Bütschli (1848–1920) Where we will genuflect?" (PDF). Protistology. 8 (1): 22–35.

- ↑ Sharp, L. W. (1921). Introduction To Cytology. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company Inc. p. 143.

- ↑ Janusz Komender (2008). "Kilka słów o doktorze Wacławie Mayzlu i jego odkryciu" [On Waclaw Mayzel and his observation of mitotic division] (PDF). Postępy Biologii Komórki (in Polish). Polskie Towarzystwo Anatomiczne, Polskie Towarzystwo Biologii Komórki. 35 (3): 405–407.

- ↑ Iłowiecki, Maciej (1981). Dzieje nauki polskiej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Interpress. p. 187. ISBN 83-223-1876-6.

- ↑ "mitosis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ μίτος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- 1 2 Blow, J.; Tanaka, T. (2005). "The chromosome cycle: coordinating replication and segregation: Second in the cycles review series". EMBO Reports. 6 (11): 1028–34. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400557. PMC 1371039

. PMID 16264427.

. PMID 16264427. - ↑ Zhou, J.; Yao, J.; Joshi, H. (2002). "Attachment and tension in the spindle assembly checkpoint". Journal of Cell Science. 115 (Pt 18): 3547–55. doi:10.1242/jcs.00029. PMID 12186941.

- 1 2 Lloyd, C.; Chan, J. (2006). "Not so divided: the common basis of plant and animal cell division". Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 7 (2): 147–52. doi:10.1038/nrm1831. PMID 16493420.

- ↑ Raven et al., 2005, pp. 58–67.

- ↑ Prasanth, K. V.; Sacco-Bubulya, P. A.; Prasanth, S. G.; Spector, D. L. (2003). "Sequential entry of components of the gene expression machinery into daughter nuclei". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 14 (3): 1043–57. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0669. PMC 151578

. PMID 12631722.

. PMID 12631722. - ↑ Kadauke, S; Blobel, G. A. (2013). "Mitotic bookmarking by transcription factors". Epigenetics & Chromatin. 6 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/1756-8935-6-6. PMC 3621617

. PMID 23547918.

. PMID 23547918. - ↑ Prescott, D. M.; Bender, M. A. (1962). "Synthesis of RNA and protein during mitosis in mammalian tissue culture cells". Experimental Cell Research. 26 (2): 260–8. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(62)90176-3. PMID 14488623.

- ↑ Olson, Mark O. J. (2011). The Nucleolus. Volume 15 of Protein Reviews. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 15. ISBN 9781461405146.

- ↑ Basto, R.; Lau, J.; Vinogradova, T.; Gardiol, A.; Woods, G.; Khodjakov, A.; Raff, W. (June 2006). "Flies without centrioles". Cell. 125 (7): 1375–1386. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025. PMID 16814722.

- ↑ Heywood, P. (1978). "Ultrastructure of mitosis in the chloromonadophycean alga Vacuolaria virescens". Journal of Cell Science. 31: 37–51. PMID 670329.

- ↑ Ribeiro, K.; Pereira-Neves, A; Benchimol, M. (2002). "The mitotic spindle and associated membranes in the closed mitosis of trichomonads". Biology of the Cell. 94 (3): 157–72. doi:10.1016/S0248-4900(02)01191-7. PMID 12206655.

- 1 2 Chan, G.; Liu, S.; Yen, T. (2005). "Kinetochore structure and function". Trends in Cell Biology. 15 (11): 589–98. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.010. PMID 16214339.

- ↑ Cheeseman, Iain M.; Desai, Arshad (January 2008). "Molecular architecture of the kinetochore–microtubule interface". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 9 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1038/nrm2310. PMID 18097444.

- 1 2 Winey, M.; Mamay, C.; O'Toole, E.; Mastronarde, D.; Giddings, T.; McDonald, K.; McIntosh, J. (1995). "Three-dimensional ultrastructural analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic spindle". Journal of Cell Biology. 129 (6): 1601–15. doi:10.1083/jcb.129.6.1601. PMC 2291174

. PMID 7790357.

. PMID 7790357. - 1 2 Maiato, H.; DeLuca, J.; Salmon, E.; Earnshaw, W. (2004). "The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface". Journal of Cell Science. 117 (Pt 23): 5461–77. doi:10.1242/jcs.01536. PMID 15509863.

- ↑ Chan, G.; Yen, T. (2003). "The mitotic checkpoint: a signaling pathway that allows a single unattached kinetochore to inhibit mitotic exit". Progress in Cell Cycle Research. 5: 431–9. PMID 14593737.

- 1 2 FitzHarris, G. (March 2012). "Anaphase B precedes anaphase A in the mouse egg". Current Biology. 22 (5): 437–444. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.041. PMID 22342753.

- ↑ Miller, K. R. g (2000). "Anaphase". Biology (5 ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 169–70. ISBN 978-0-13-436265-6.

- ↑ "Chromosome condensation through mitosis". Science Daily. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ↑ Glotzer, M. (2005). "The molecular requirements for cytokinesis". Science. 307 (5716): 1735–9. doi:10.1126/science.1096896. PMID 15774750.

- ↑ Albertson, R.; Riggs, B.; Sullivan, W. (2005). "Membrane traffic: a driving force in cytokinesis". Trends in Cell Biology. 15 (2): 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.12.008. PMID 15695096.

- ↑ Raven et al., 2005, pp. 64–7, 328–9.

- 1 2 Lilly, .M; Duronio, R. (2005). "New insights into cell cycle control from the Drosophila endocycle". Oncogene. 24 (17): 2765–75. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208610. PMID 15838513.

- ↑ Sauer, F. C. (1935). "Mitosis in the neural tube". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 62 (2): 377–405. doi:10.1002/cne.900620207.

- 1 2 Meyer, E. J. (2011). "Interkinetic Nuclear Migration Is a Broadly Conserved Feature of Cell Division in Pseudostratified Epithelia". Current Biology. 21 (6): 485–491. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.002. PMID 21376598.

- 1 2 Luxenburg, Chen; et al. (2011). "Developmental roles for Srf, cortical cytoskeleton and cell shape in epidermal spindle orientation". Nature Cell Biology. 13 (3): 203–U51. doi:10.1038/Ncb2163. PMID 21336301.

- ↑ Nakajima, Yu-Ichiro; Meyer, Emily J; Kroesen, Amanda; McKinney, Sean A; Gibson, Matthew C (2013). "Epithelial junctions maintain tissue architecture by directing planar spindle orientation". Nature. 500 (7462): 359–362. doi:10.1038/nature12335. PMID 23873041.

- 1 2 Cadart, C.; Zlotek-Zlotkiewicz, E.; Le Berre, M.; Piel, M.; Matthews, H. K. (2014). "Exploring the Function of Cell Shape and Size during Mitosis". Developmental Cell. 29 (2): 159–169. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.009. PMID 24780736.

- ↑ Lancaster, Oscar; et al. (2013). "Mitotic rounding alters cell geometry to ensure efficient bipolar spindle formation". Developmental Cell. 25 (2): 270–283. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.014. PMID 23623611.

- 1 2 Lancaster, Oscar; Baum, Buzz (2014). "Shaping up to divide: Coordinating actin and microtubule cytoskeletal remodelling during mitosis". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 34: 109–115. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.015. PMID 24607328.

- 1 2 3 Maddox, A. S.; Burridge, K. (2003). "RhoA is required for cortical retraction and rigidity during mitotic cell rounding". Journal of Cell Biology. 160 (2): 255–265. doi:10.1083/jcb.200207130. PMID 12538643.

- 1 2 Matthews, H. K.; et al. (2012). "Changes in ect2 localization couple actomyosin-dependent cell shape changes to mitotic progression". Developmental Cell. 23 (2): 371–383. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.003. PMID 22898780.

- 1 2 Stewart, M. P.; Helenius, J.; Toyoda, Y.; Ramanathan, S. P.; Muller, D. J.; Hyman, A. A. (2011). "Hydrostatic pressure and the actomyosin cortex drive mitotic cell rounding". Nature. 469 (7329): 226–230. doi:10.1038/nature09642. PMID 21196934.

- ↑ Fischer-Friedrich, Elizabeth; et al. (2014). "Quantification of surface tension and internal pressure generated by single mitotic cells". Scientific Reports. 4 (6213). doi:10.1038/srep06213. PMID 25169063.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramanathan, S. P.; et al. (2015). "Cdk1-dependent mitotic enrichment of cortical myosin II promotes cell rounding against confinement". Nature Cell Biology. 17 (2): 148–159. doi:10.1038/ncb3098. PMID 25621953.

- ↑ Mantikou, E.; Wong, K.M.; Repping, S.; Mastenbroek, S. (December 2012). "Molecular origin of mitotic aneuploidies in preimplantation embryos". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1822 (12): 1921–1930. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.06.013. PMID 22771499.

- ↑ Draviam, V.; Xie, S.; Sorger, P. (2004). "Chromosome segregation and genomic stability". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 14 (2): 120–5. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2004.02.007. PMID 15196457.

- 1 2 3 Iourov, I.Y.; Vorsanova, S.G.; Yurov, Y.B. (2006). "Chromosomal Variations in Mammalian Neuronal Cells: Known Facts and Attractive Hypotheses". In Jeon, Kwang J. International Review Of Cytology: A Survey of Cell Biology. 249. Waltham, MA: Academic Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780080463506.

- ↑ Shi, Q.; King, R.W. (October 2005). "Chromosome nondisjunction yields tetraploid rather than aneuploid cells in human cell lines". Nature. 437 (7061): 1038–1042. doi:10.1038/nature03958. PMID 16222248.

- 1 2 Edgar, B.A.; Orr-Weaver, T.L. (May 2001). "Endoreplication Cell Cycles: More for Less". Cell. 105 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00334-8. PMID 11348589.

- 1 2 Lee, H.O.; Davidson, J.M.; Duronio, R.J. (2009). "Endoreplication: polyploidy with purpose". Genes & Development. 23 (21): 2461–2477. doi:10.1101/gad.1829209. PMC 2779750

. PMID 19884253.

. PMID 19884253. - ↑ Italiano, J. E.; Shivdasani, R. A. (2003). "Megakaryocytes and beyond: the birth of platelets". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1 (6): 1174–82. doi:10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00290.x. PMID 12871316.

- ↑ Vitrat, N.; Cohen-Solal, K.; Pique, C.; LeCouedic, J.P.; Norol, F.; Larsen, A.K.; Katz, A.; Vainchenker, W.; Debili, N. (May 1998). "Endomitosis of Human Megakaryocytes Are Due to Abortive Mitosis". Blood. 91 (10): 3711–3723. PMID 9573008.

Cited texts

- Raven, P. H.; Evert, R. F.; Eichhorn, S. E. (2005). Biology of Plants (7th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 0716710072.

Further reading

- Morgan, David L. (2007). The cell cycle: principles of control. London: Published by New Science Press in association with Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-9539181-2-2.

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. (2002). "Mitosis". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science. Retrieved 2006-01-22.

- Campbell, N.; Reece, J. (December 2001). "The Cell Cycle". Biology (6th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings/Addison-Wesley. pp. 217–224. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5.

- Cooper, G. (2000). "The Events of M Phase". The Cell: A Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Sinaeur Associates, Inc. Retrieved 2006-01-22.

- Freeman, S. (2002). "Cell Division". Biological Science. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 155–174. ISBN 0-13-081923-9.

- Lodish, H.; Berk, A.; Zipursky, L.; Matsudaira, P.; Baltimore, D.; Darnell, J. (2000). "Overview of the Cell Cycle and Its Control". Molecular Cell Biology (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. Retrieved 2006-01-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mitosis. |

- A Flash animation comparing Mitosis and Meiosis

- Khan Academy, lecture

- Studying Mitosis in Cultured Mammalian Cells

- General K-12 classroom resources for Mitosis

- The Cell-Cycle Ontology

- WormWeb.org: Interactive Visualization of the C. elegans Cell Lineage – Visualize the entire cell lineage tree and all of the cell divisions of the nematode C. elegans