Misoprostol

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cytotec, Misodel, other |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a689009 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, vaginal, under the tongue |

| ATC code | A02BB01 (WHO) G02AD06 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | extensively absorbed |

| Protein binding | 80-90% (active metabolite, misoprostol acid) |

| Metabolism | Liver (extensive to misoprostic acid) |

| Biological half-life | 20–40 minutes |

| Excretion | Urine (80%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

59122-46-2 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5282381 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 1936 |

| DrugBank |

DB00929 |

| ChemSpider |

4445541 |

| UNII |

0E43V0BB57 |

| KEGG |

D00419 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL606 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.190.521 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

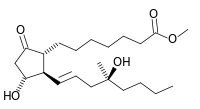

| Formula | C22H38O5 |

| Molar mass | 382.534 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Misoprostol, sold under the brandname Cytotec among others, is a medication used to start labor, cause an abortion, prevent and treat stomach ulcers, and treat postpartum bleeding due to poor contraction of the uterus.[1] For abortions it is often used with mifepristone or methotrexate.[2] By itself effectiveness for this purpose is between 66% and 90%.[3] It is taken either by mouth, under the tongue, or placed in the vagina.[2][4]

Common side effects include diarrhea and abdominal pain. It is pregnancy category X meaning that it is known to result in negative outcomes for the baby if taken during pregnancy. Uterine rupture may occur. It is a prostaglandin analogue — specifically, a synthetic prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).[1]

Misoprostol was developed in 1973.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[1] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 0.36 to 2.00 USD a dose.[7] A months supply to treat stomach ulcers in the United States is between 100 and 200 USD.[8] The same costs between 30 and 55 EUR in Europe.[9]

Medical uses

Ulcer prevention

Misoprostol is used for the prevention of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers. It acts upon gastric parietal cells, inhibiting the secretion of gastric acid by G-protein coupled receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase, which leads to decreased intracellular cyclic AMP levels and decreased proton pump activity at the apical surface of the parietal cell. Because other classes of drugs, especially H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors, are more effective for the treatment of acute peptic ulcers, misoprostol is only indicated for use by people who are both taking NSAIDs and are at high risk for NSAID-induced ulcers, including the elderly and people with ulcer complications. Misoprostol is sometimes coprescribed with NSAIDs to prevent their common adverse effect of gastric ulceration (e.g. with diclofenac in Arthrotec).

Misoprostol has other protective actions, but is only clinically effective at doses high enough to reduce gastric acid secretion. For instance, at lower doses, misoprostol may stimulate increased secretion of the protective mucus that lines the gastrointestinal tract and increase mucosal blood flow, thereby increasing mucosal integrity. However, these effects are not pronounced enough to warrant prescription of misoprostol at doses lower than those needed to achieve gastric acid suppression.

However, even in the treatment of NSAID-induced ulcers, omeprazole proved to be at least as effective as misoprostol,[10] but was significantly better tolerated, so misoprostol should not be considered a first-line treatment. Misoprostol-induced diarrhea and the need for multiple daily doses (typically four) are the main issues impairing compliance with therapy.

Labor induction

Misoprostol is commonly used for labor induction. It causes uterine contractions and the ripening (effacement or thinning) of the cervix.[11] It can be less expensive than the other commonly used ripening agent, dinoprostone.[12]

Oxytocin has long been used as the standard agent for labor induction, but does not work well when the cervix is not yet ripe. Misoprostol also may be used in conjunction with oxytocin.[12]

The US FDA in 2002 approved misoprostol for the purpose of labor induction.[13] Between 2002 and 2012, a misoprostol vaginal insert was studied, and was approved in the EU.[14][15]

Abortion

Misoprostol is used either alone or in conjunction with an other medication (mifepristone or methotrexate) for medical abortions as an alternative to surgical abortion.[16] Medical abortion has the advantage of being less invasive, and more autonomous, self-directed, and discreet. It is preferable to users because it feels more "natural," as the drugs induce a miscarriage.[17] It is also more easily accessible in places where abortion is illegal.[18] The World Health Organization provides clear guidelines on the use, benefits and risks of misoprostol for abortions.[19]

Misoprostol is most effective when it is used with methotrexate or mifepristone (RU-486).[20] Misoprostol alone is less effective (typically 88% up to eight-weeks gestation). It is not inherently unsafe if medically supervised, but 1% of women will have heavy bleeding requiring medical attention, some women may have ectopic pregnancy, and the 12% of pregnancies that continue after misoprostol failure are more likely to have birth defects and are usually followed up with a more effective method of abortion.[21]

Most large studies recommend a protocol for the use of misoprostol in combination with mifepristone.[22] Together they are effective in around 95% for early pregnancies.[23] Misoprostol alone may be more effective in earlier gestation.[24] WHO guidelines recommend for pregnancies up to 12 weeks to use up to 4 doses of misoprostol under the tongue or in the vagina with at least 3 hour intervals between doses.[20] It works in 90% after first attempt and, in case of failure, the attempt may be repeated after a minimum of 3 days.

Misoprostol can also be used to dilate the cervix in preparation for a surgical abortion, particularly in the second trimester (either alone or in combination with laminaria stents).

Missed miscarriage

Misoprostol is sometimes used to treat early fetal death in the absence of spontaneous miscarriage, but further research is needed to establish a safe, effective protocol.[25]

Misoprostol is regularly used in some Canadian hospitals for labour induction for fetal deaths early in pregnancy, and for termination of pregnancy for fetal anomalies. A low dose is used initially, then doubled for the remaining doses until delivery. In the case of a previous Caesarian section, however, lower doses are used.

Postpartum bleeding

Misoprostol is also used to prevent and treat post-partum bleeding. Orally administered misoprostol was marginally less effective than oxytocin.[26] The use of rectally administered misoprostol is optimal in cases of bleeding; it was shown to be associated with lower rates of side effects compared to other routes. Rectally administered misoprostol was reported in a variety of case reports and randomised controlled trials.[27][28] However, it is inexpensive and thermostable (thus does not require refrigeration like oxytocin), making it a cost-effective and valuable drug to use in the developing world.[29] A randomised control trial of misoprostol use found a 38% reduction in maternal deaths due to post partum haemorrhage in resource-poor communities.[30] Misoprostol is recommended due to its cost, effectiveness, stability, and low rate of side effects.[31] Oxytocin must also be given by injection, while misprostol can be given orally or rectally for this use, making it much more useful in areas where nurses and physicians are less available.[32]

Adverse effects

The most commonly reported adverse effect of taking a misoprostol orally for the prevention of stomach ulcers is diarrhea. In clinical trials, an average 13% of patients reported diarrhea, which was dose-related and usually developed early in the course of therapy (after 13 days) and was usually self-limiting (often resolving within 8 days), but sometimes (in 2% of patients) required discontinuation of misoprostol.[33]

The next most commonly reported adverse effects of taking misoprostol orally for the prevention of gastric ulcers are: abdominal pain, nausea, flatulence, headache, dyspepsia, vomiting, and constipation, but none of these adverse effects occurred more often than when taking placebos.[33] In practice, fever is almost universal when multiple doses are given every 4 to 6 hours.

Misoprostol should not be taken by pregnant women to reduce the risk of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers because it increases uterine tone and contractions in pregnancy, which may cause partial or complete abortions, and because its use in pregnancy has been associated with birth defects.[33][34]

All cervical ripening and induction agents can cause uterine hyperstimulation, which can negatively affect the blood supply to the fetus and increases the risk of complications such as uterine rupture.[35] Concern has been raised that uterine hyperstimulation that occurs during a misoprostol-induced labor is more difficult to treat than hyperstimulation during labors induced by other drugs.[36] Because the complications are rare, it is difficult to determine if misoprostol causes a higher risk than do other cervical ripening agents. One estimate is that it would require around 61,000 people enrolled in randomized controlled trials to detect a difference in serious fetal complications and about 155,000 people to detect a difference in serious maternal complications.[37]

Pharmacology

Misoprostol, a prostaglandin analogue, binds to myometrial cells to cause strong myometrial contractions leading to expulsion of tissue. This agent also causes cervical ripening with softening and dilation of the cervix.

Society and culture

A letter from Searle generated some controversy over the use of misoprostol in labor inductions.[38] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists holds that substantial evidence supports the use of misoprostol for induction of labor, a position it reaffirmed in 2000 in response to the Searle letter.[39] Misoprostol is also on the WHO essential drug list for labor induction.[40]

The largest medical malpractice award of nearly $70 million was awarded due to the use of misoprostol to induce labor in a California hospital.[41]

A vaginal form of the medication is sold in the EU under the names Misodel and Mysodelle for use in labor induction.

Black market

Misoprostol is used for self-induced abortions in Brazil, where black market prices exceed US$100 per dose. Illegal medically unsupervised misoprostol abortions in Brazil are associated with a lower complication rate than other forms of illegal self-induced abortion, but are still associated with a higher complication rate than legal, medically supervised surgical and medical abortions. Failed misoprostol abortions are associated with birth defects in some cases.[42][43][44][45][46] Poor immigrant populations in New York City have also been observed to use self-administered misoprostol to induce abortions, as this method is much cheaper than a surgical abortion (about $2 per dose).[47] The drug is readily available in Mexico.[48] Use of misoprostol has also increased in Texas in response to increased regulation of abortion providers.[49]

References

- 1 2 3 "Misoprostol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Feb 20, 2015.

- 1 2 Kulier, R; Kapp, N; Gülmezoglu, AM; Hofmeyr, GJ; Cheng, L; Campana, A (9 November 2011). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (11): CD002855. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub4. PMID 22071804.

- ↑ Bryant, AG; Regan, E; Stuart, G (January 2014). "An overview of medical abortion for clinical practice.". Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 69 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000017. PMID 25102250.

- ↑ Marret, H; Simon, E; Beucher, G; Dreyfus, M; Gaudineau, A; Vayssière, C; Lesavre, M; Pluchon, M; Winer, N; Fernandez, H; Aubert, J; Bejan-Angoulvant, T; Jonville-Bera, AP; Clouqueur, E; Houfflin-Debarge, V; Garrigue, A; Pierre, F; Collège national des gynécologues obstétriciens, français (April 2015). "Overview and expert assessment of off-label use of misoprostol in obstetrics and gynaecology: review and report by the Collège national des gynécologues obstétriciens français.". European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 187: 80–4. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.01.018. PMID 25701235.

- ↑ Paul, Maureen (2011). "Misoprostol". Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy: Comprehensive Abortion Care. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444358476.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Misoprostol". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 271. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ "DocMorris - Cytotec 200 µg Tabletten". 6 May 2016. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepañski L, et al. (March 1998). "Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (11): 727–34. doi:10.1056/NEJM199803123381105. PMID 9494149.

- ↑ Wood, Alastair J. J.; Goldberg, Alisa B.; Greenberg, Mara B.; Darney, Philip D. (2001). "Misoprostol and Pregnancy". New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440107. PMID 11136959.

- 1 2 Summers, L (1997). "Methods of cervical ripening and labor induction". Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 42 (2): 71–85. doi:10.1016/S0091-2182(96)00138-3. PMID 9107114.

- ↑ "Induction of Labor Number 107" (PDF). August 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "Ferring's removable misoprostol vaginal delivery system, approved for labour induction in European Decentralised Procedure". Ferring. 17 October 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Wing, Deborah. "Misoprostol Vaginal Insert and Time to Vaginal Delivery: A Randomized Controlled Trial". Obstetrics and gynaecology. Wolters Kluwer Health. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ↑ "WHO | Medical methods for first trimester abortion". apps.who.int. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Harvey, S. M.; Beckman, L. J.; Castle, M. A.; Coeytaux, F. (1995-10-01). "Knowledge and perceptions of medical abortion among potential users". Family Planning Perspectives. 27 (5): 203–207. doi:10.2307/2136276. ISSN 0014-7354. PMID 9104607.

- ↑ Bazelon, Emily (2014-08-28). "The Dawn of the Post-Clinic Abortion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ "Medical methods for first trimester abortion". The WHO Medical Reproductive Library. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- 1 2 Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems World Health Organization, 2012

- ↑ What is the "Mexican abortion pill" and how safe is it? Jen Gunter, July 27, 2013

- ↑ "Annotated Bibliography on Misoprostol Alone for Early Abortion" (PDF). Gynuity Health Projects. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ providing medical abortion in low-resource settings (PDF) (2 ed.). Gynuity Health Projects. 2009. p. 4.

- ↑ "Instructions for Use: Abortion Induction with Misoprostol in Pregnancies up to 9 Weeks LMP" (PDF). Gynuity Health Projects. 2003. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ Neilson, James P; Hickey, Martha; Vazquez, Juan C (2006). Neilson, James P, ed. "Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD002253. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002253.pub3. PMID 16855990.

- ↑ Villar, J; Gülmezoglu, AM; Hofmeyr, GJ; Forna, F (2002). "Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of misoprostol to prevent postpartum hemorrhage". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 100 (6): 1301–12. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02371-2. PMID 12468178.

- ↑ O'Brien, P; El-Refaey, H; Gordon, A; Geary, M; Rodeck, CH (1998). "Rectally administered misoprostol for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage unresponsive to oxytocin and ergometrine: A descriptive study". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 92 (2): 212–4. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00161-6. PMID 9699753.

- ↑ Lokugamage, Amali U.; Sullivan, Keith R.; Niculescu, Iosif; Tigere, Patrick; Onyangunga, Felix; Refaey, Hazem El; Moodley, Jagidesa; Rodeck, Charles H. (2001). "A randomized study comparing rectally administered misoprostol versus Syntometrine combined with an oxytocin infusion for the cessation of primary post partum hemorrhage". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 80 (9): 835–9. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080009835.x. PMID 11531635.

- ↑ Bradley, S. E. K.; Prata, N.; Young-Lin, N.; Bishai, D.M. (2007). "Cost-effectiveness of misoprostol to control postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 97 (1): 52–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.12.005. PMID 17316646.

- ↑ Derman, Richard J; Kodkany, Bhalchandra S; Goudar, Shivaprasad S; Geller, Stacie E; Naik, Vijaya A; Bellad, MB; Patted, Shobhana S; Patel, Ashlesha; et al. (2006). "Oral misoprostol in preventing postpartum haemorrhage in resource-poor communities: A randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. 368 (9543): 1248–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69522-6. PMID 17027730.

- ↑ Sanghvi, Harshad; Zulkarnain, Mohammad; Chanpong, Gail Fraser (2009). Blouse, Ann; Lewison, Dana, eds. Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage at Home Birth: A Program Implementation Guide (PDF). United States Agency for International Development.

- ↑ Prata, Ndola; Passano, Paige; Bell, Suzanne; Rowen, Tami; Potts, Malcolm (2012). "New hope: community-based misoprostol use to prevent postpartum haemorrhage". Health Policy and Planning. 368: 339–46. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs068. PMID 22879523.

- 1 2 3 Pfizer (September 2006). "Cytotec US Prescribing Information" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Pharmacia (July 2004). "Cytotec UK SPC (Summary of Product Characteristics)". Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Briggs, G. G.; Wan, SR (2006). "Drug therapy during labor and delivery, part 2". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 63 (12): 1131–9. doi:10.2146/ajhp050265.p2. PMID 16754739.

- ↑ Wagner 2006

- ↑ Goldberg & Wing 2003, which cites:

- Weeks, Andrew; Alfirevic, Zarko (2006). "Oral Misoprostol Administration for Labor Induction". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 49 (3): 658–71. doi:10.1097/00003081-200609000-00023. PMID 16885670.

- ↑ Goldberg, A; Wing, D (2003). "Induction of laborthe misoprostol controversy". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 48 (4): 244–8. doi:10.1016/S1526-9523(03)00087-4. PMID 12867908.

- ↑ Goldberg & Wing 2003, which cites:

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (November 1999). "Induction of labor with misoprostol". ACOG committee opinion no. 228. Washington, DC.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (November 1999). "Response to Searle's drug warning on misoprostol". ACOG committee opinion no. 248. Washington, DC.

- ↑ WHO. "WHO Essential drug list 2005 section 22.1 website" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ↑ "Denver attorney receives 'Case of the Year' honor".

- ↑ Costa, S. H.; Vessey, M. P. (1993). "Misoprostol and illegal abortion in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil". The Lancet. 341 (8855): 1258–61. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)91156-G. PMID 8098402.

- ↑ Coêlho, Helena Lutéscia; Teixeira, Ana Cláudia; De Fátima Cruz, Maria; Gonzaga, Sandra Luzia; Arrais, Paulo Sérgio; Luchini, Laura; La Vecchia, Carlo; Tognoni, Gianni (1994). "Misoprostol: The experience of women in Fortaleza, Brazil". Contraception. 49 (2): 101–10. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(94)90084-1. PMID 8143449.

- ↑ Barbosa, Regina Maria; Arilha, Margareth (1993). "The Brazilian Experience with Cytotec". Studies in Family Planning. 24 (4): 236–40. doi:10.2307/2939191. JSTOR 2939191. PMID 8212093.

- ↑ Rocha, J. (1994). "Brazil investigates drug's possible link with birth defects". BMJ. 309 (6957): 757–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6957.757a. PMC 2540993

. PMID 7950553.

. PMID 7950553. - ↑ Gonzalez, Claudette Hajaj; Vargas, Fernando R.; Perez, Ana Beatriz Alvarez; Kim, Chong Ae; Brunoni, Decio; Marques-Dias, Maria Joaquina; Leone, Clea R.; Neto, Jordão Correa; et al. (1993). "Limb deficiency with or without Möbius sequence in seven Brazilian children associated with misoprostol use in the first trimester of pregnancy". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 47 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320470113. PMID 8368254.

- ↑ John Leland (October 2, 2005). "Abortion Might Outgrow Its Need for Roe v. Wade". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Erik Eckholm (July 13, 2013). "In Mexican Pill, a Texas Option for an Abortion". The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ↑ Erica Hellenstein (June 27, 2014). "The Rise of the DIY Abortion in Texas". The Atlantic.

External links

- Misoprostol.org an independent website containing dosage guidelines and advice on misoprostol use.

- The Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology of Mifepristone, Misoprostol, and Methotrexate