Silybum marianum

| Milk thistle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Tribe: | Cynareae |

| Genus: | Silybum |

| Species: | S. marianum |

| Binomial name | |

| Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carduus marianus L. | |

_by_Musli_Berisha-_mibe.jpg)

Silybum marianum has other common names include cardus marianus, milk thistle,[1] blessed milkthistle,[2] Marian thistle, Mary thistle, Saint Mary's thistle, Mediterranean milk thistle, variegated thistle and Scotch thistle. This species is an annual or biennial plant of the Asteraceae family. This fairly typical thistle has red to purple flowers and shiny pale green leaves with white veins. Originally a native of Southern Europe through to Asia, it is now found throughout the world.

Description

Milk thistles can grow to be 30 to 200 cm (12 to 79 in) tall, and have an overall conical shape. The approximate maximum base diameter is 160 cm (63 in). The stem is grooved and more or less cottony. The largest specimens have hollow stems.

The leaves are oblong to lanceolate. They are either lobate or pinnate, with spiny edges. They are hairless, shiny green, with milk-white veins.

The flower heads are 4 to 12 cm long and wide, of red-purple colour. They flower from June to August in the North or December to February in the Southern Hemisphere (summer through autumn).

The bracts are hairless, with triangular, spine-edged appendages, tipped with a stout yellow spine.

The achenes are black, with a simple long white pappus, surrounded by a yellow basal ring.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Possibly native near the coast of southeast England, it has been widely introduced outside its natural range, for example into North America, Iran, Australia and New Zealand where it is considered an invasive weed. Cultivated fields for the production of raw material for the pharmaceutical industry exist on a larger scale in Austria (Waldviertel region), Germany, Hungary, Poland, China and Argentina. In Europe it is sown yearly in March–April. The harvest in two steps (cutting and threshing) takes place in August, about 2–3 weeks after the flowering.

Exkursionsflora Fuer Kreta by Jahn & Schoenfelder (1995, page 326) states that the distribution is mediterranean-near east. They quote it as a native plant of Crete, Greece.

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) is a thorny plant presenting decorative leaves with a white pattern of veins and purple flower heads. The plant originates from mountains of the Mediterranean region, where it forms scrub on a rocky base.

The plant is sometimes also used as a decorative element in gardens, and its dried flower heads may be used for the decoration of dry bouquets.

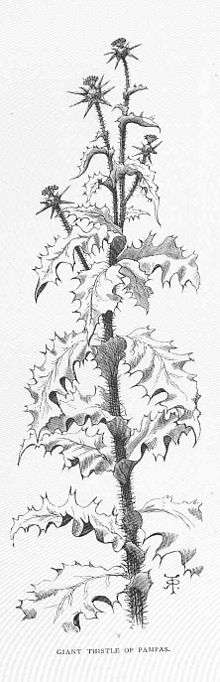

The "giant thistle of the Pampas" reported by Darwin in the Voyage of the Beagle[4] is thought by some to be Silybum marianum.[5][6]

Chemistry

Traditional milk thistle extract is made from the seeds, which contain approximately 4–6% silymarin.[7] The extract consists of about 65–80% silymarin (a flavonolignan complex) and 20–35% fatty acids, including linoleic acid.[8] Silymarin is a complex mixture of polyphenolic molecules, including seven closely related flavonolignans (silybin A, silybin B, isosilybin A, isosilybin B, silychristin, isosilychristin, silydianin) and one flavonoid (taxifolin).[8] Silibinin, a semipurified fraction of silymarin, is primarily a mixture of 2 diastereoisomers, silybin A and silybin B, in a roughly 1:1 ratio.[8][9]

Medicinal use

Clinical trials

Milk thistle has been researched for a number of purposes including treatment of liver disease, and cancer; however, clinical studies are largely heterogeneous and contradictory.[10]

In trials, silymarin has typically been administered in amounts ranging from 420–480 mg per day in two to three divided doses.[10] However, higher doses have been studied, such as 600 mg daily in the treatment of type II diabetes[11] (with significant results), and 600 or 1200 mg daily in patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus [12] (without significant results). An optimal dosage for milk thistle preparations has not been established.

Herbal medicinal research

Silybum marianum is used in traditional Chinese medicine to clear heat and relieve toxic material, to soothe the liver and to promote bile flow.[13] Though its efficacy in treating diseases is still unknown, Silybum marianum is sometimes prescribed by herbalists to help treat liver diseases (cirrhosis, jaundice and hepatitis). Both in vitro and animal research suggest that Silibinin (syn. silybin, sylimarin I) may have hepatoprotective (antihepatotoxic) properties that protect liver cells against toxins.[14][15][16]

A 2000 study of such claims by the AHRQ concluded that "clinical efficacy of milk thistle is not clearly established". A 2005 Cochrane Review considered thirteen randomized clinical trials which assessed milk thistle in 915 patients with alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases. They question the beneficial effects of milk thistle for patients with alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases and highlight the lack of high-quality evidence to support this intervention. Cochrane concluded that more good-quality randomized clinical trials on milk thistle versus placebo are needed.[17]

Cancer Research UK say that milk thistle is promoted on the internet for its claimed ability to slow certain kinds of cancer, but that there is no good evidence in support of these claims.[18]

Safety

Milk thistle extracts are known to be safe and well-tolerated.[19] Milk thistle supplements, however, were measured to have the highest mycotoxin concentrations of up to 37 mg/kg when compared amongst various plant-based dietary supplements.[20]

Use as food

Milk thistle has also been known to be used as food. The roots can be eaten raw or boiled and buttered or par-boiled and roasted. The young shoots in spring can be cut down to the root and boiled and buttered. The spiny bracts on the flower head were eaten in the past like globe artichoke, and the stems (after peeling) can be soaked overnight to remove bitterness and then stewed. The leaves can be trimmed of prickles and boiled as a spinach substitute or they can also be added raw to salads.

Animal toxicity

Because of potassium nitrate content, the plant has been found to be toxic to cattle and sheep. When potassium nitrate is eaten by ruminants, the bacteria in the animal's stomach breaks the chemical down, producing nitrite ions. Nitrite ions then combine with hemoglobin to produce methaemoglobin, blocking the transport of oxygen. The result is a form of oxygen deprivation.[21]

References

- ↑ "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-02-25. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ "Silphium marianum". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ↑ Rose, Francis (1981). The Wild Flower Key. Frederick Warne. pp. 388–9. ISBN 0-7232-2419-6.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles Robert. The Voyage of the Beagle. Vol. XXIX. The Harvard Classics. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909–14; Bartleby.com, 2001. www.bartleby.com/29/ [accessed 30 Sep 2016] Ch VI.

- ↑ Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club (Torrey Botanical Club, 1887), p. 163

- ↑ The Rise of Capitalism on the Pampas: The Estancias of Buenos Aires, 1785-1870, By Samuel Amaral (Cambridge University Press,2002) p. 129

"Charles Darwin, who visited the pampas while traveling around the world, refers to Cynara cardunculus as cardoon, differentiating it from the great thistle, which scientific designation does not mention, described by F. B. Head. The former was as high as a horse; the second, higher than the head of a horserider. In Far Away and Long Ago, William Henry Hudson mentions two types: the cardoon thistle, or wild artichoke, of a bluish or grey-greenish color, and the giant thistle, cardo asnal for the natives and Carduus marianum for botanists, with white and green leaves." - ↑ Greenlee, H.; Abascal, K.; Yarnell, E.; Ladas, E. (2007). "Clinical Applications of Silybum marianum in Oncology". Integrative Cancer Therapies. 6 (2): 158–65. doi:10.1177/1534735407301727. PMID 17548794.

- 1 2 3 Kroll, D. J.; Shaw, H. S.; Oberlies, N. H. (2007). "Milk Thistle Nomenclature: Why It Matters in Cancer Research and Pharmacokinetic Studies". Integrative Cancer Therapies. 6 (2): 110–9. doi:10.1177/1534735407301825. PMID 17548790.

- ↑ Hogan, Fawn S.; Krishnegowda, Naveen K.; Mikhailova, Margarita; Kahlenberg, Morton S. (2007). "Flavonoid, Silibinin, Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Cell-Cycle Arrest of Human Colon Cancer". Journal of Surgical Research. 143 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.080. PMID 17950073.

- 1 2 Rainone, Francine (2005). "Milk Thistle". American Family Physician. 72 (7): 1285–8. PMID 16225032.

- ↑ Huseini, H. Fallah; Larijani, B.; Heshmat, R.; Fakhrzadeh, H.; Radjabipour, B.; Toliat, T.; Raza, Mohsin (2006). "The efficacy of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (silymarin) in the treatment of type II diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial". Phytotherapy Research. 20 (12): 1036–9. doi:10.1002/ptr.1988. PMID 17072885.

- ↑ Gordon, Adam; Hobbs, Daryl A; Bowden, D Scott; Bailey, Michael J; Mitchell, Joanne; Francis, Andrew JP; Roberts, Stuart K (2006). "Effects ofSilybum marianumon serum hepatitis C virus RNA, alanine aminotransferase levels and well-being in patients with chronic hepatitis C". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 21 (1 Pt 2): 275–80. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04138.x. PMID 16460486.

- ↑ Wang L, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, et al. (July 2014). "Natural product agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ): a review". Biochemical Pharmacology. 92: 73–89. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.018. PMC 4212005

. PMID 25083916.

. PMID 25083916. - ↑ Davis-Searles PR, Nakanishi Y, Kim NC, et al. (May 2005). "Milk thistle and prostate cancer: differential effects of pure flavonolignans from Silybum marianum on antiproliferative end points in human prostate carcinoma cells". Cancer Research. 65 (10): 4448–57. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4662. PMID 15899838.

- ↑ Al-Anati L, Essid E, Reinehr R, Petzinger E (2009). "Silibinin protects OTA-mediated TNF-alpha release from perfused rat livers and isolated rat Kupffer cells". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 53 (4): 460–6. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200800110. PMID 19156713.

- ↑ Jayaraj R, Deb U, Bhaskar AS, Prasad GB, Rao PV (2007). "Hepatoprotective efficacy of certain flavonoids against microcystin induced toxicity in mice". Environmental Toxicology. 22 (5): 472–9. doi:10.1002/tox.20283. PMID 17696131.

- ↑ Rambaldi A, Jacobs BP, Gluud C (2007). "Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003620. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003620.pub3. PMID 17943794.

- ↑ "Milk thistle and liver cancer". Cancer Research UK. 8 March 2015. Retrieved March 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Tamayo C, Diamond S (2007). "Review of clinical trials evaluating safety and efficacy of milk thistle (Silybum marianum [L.] Gaertn.)" (PDF). Integrative Cancer Therapies. 6 (2): 146–57. doi:10.1177/1534735407301942. PMID 17548793. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

Milk thistle extracts are known to be safe and well tolerated, and toxic or adverse effects observed in the reviewed clinical trials seem to be minimal.

- ↑ Veprikova Z, Zachariasova M, Dzuman Z, Zachariasova A, Fenclova M, Slavikova P, Vaclavikova M, Mastovska K, Hengst D, Hajslova J (2015). "Mycotoxins in Plant-Based Dietary Supplements: Hidden Health Risk for Consumers". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 63 (29): 6633–43. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02105. PMID 26168136. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

The highest mycotoxin concentrations were found in milk thistle-based supplements (up to 37 mg/kg in the sum).

- ↑ http://tncweeds.ucdavis.edu/esadocs/documnts/silymar.html[]

Further reading

- Milk Thistle: Effects on Liver Disease and Cirrhosis and Clinical Adverse Effects AHRQ report

- PDR for Herbal Medicines, Third Edition (ISBN 1-56363-512-7)

- Everist, S.L. (1974) Poisonous Plants of Australia Revised edition. pp. 185–187. (Angus & Robertson: Sydney) ISBN 0-207-14228-9

- Parsons, W.T. & Cuthbertson, E.G. (2001) Noxious Weeds of Australia. 2nd edn. pp. 229–233 (CSIRO: Collingwood) ISBN 0-643-06514-8.

- Rambaldi, Andrea; Jacobs, Bradly P; Gluud, Christian (2007). Rambaldi, Andrea, ed. "Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003620. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003620.pub3. PMID 17943794.

- UC Davis profile

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silybum marianum. |