Microtubule

Microtubules (micro- + tube + -ule) are a component of the cytoskeleton, found throughout the cytoplasm. These tubular polymers of tubulin can grow as long as 50 micrometres and are highly dynamic. The outer diameter of a microtubule is about 24 nm while the inner diameter is about 12 nm. They are found in eukaryotic cells, as well as some bacteria,[1] and are formed by the polymerization of a dimer of two globular proteins, alpha and beta tubulin.[2]

Microtubules are very important in a number of cellular processes. They are involved in maintaining the structure of the cell and, together with microfilaments and intermediate filaments, they form the cytoskeleton. They also make up the internal structure of cilia and flagella.They provide platforms for intracellular transport and are involved in a variety of cellular processes, including the movement of secretory vesicles, organelles, and intracellular macromolecular assemblies (see entries for dynein and kinesin).[3] They are also involved in chromosome separation (mitosis and meiosis), and are the major constituents of mitotic spindles, which are used to pull apart eukaryotic chromosomes.

Microtubules are nucleated and organized by microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs), such as the centrosome found in the center of many animal cells or the basal bodies found in cilia and flagella, or the spindle pole bodies found in most fungi.

There are many proteins that bind to microtubules, including the motor proteins kinesin and dynein, severing proteins like katanin, and other proteins important for regulating microtubule dynamics.[4] Recently an actin-like protein has been found in a gram-positive bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, which forms a microtubule-like structure and is involved in plasmid segregation.[5]

History

Tubulin and microtubule-mediated processes, like cell locomotion, were seen by early microscopists, like Leeuwenhoek (1677). However, the fibrous nature of flagella and other structures were discovered two centuries later, with improved light microscopes, and confirmed in the 20th with electron microscope and biochemical studies.[6]

Structure

In eukaryotes, microtubules are long, hollow cylinders made up of polymerised α- and β-tubulin dimers.[8] The inner space of the hollow microtubule cylinders is referred to as the lumen. The α and β-tubulin subunits are approximately 50% identical at the amino acid level, and each have a molecular weight of approximately 50 kDa.[9]

These α/β-tubulin dimers polymerize end-to-end into linear protofilaments that associate laterally to form a single microtubule, which can then be extended by the addition of more α/β-tubulin dimers. Typically, microtubules are formed by the parallel association of thirteen protofilaments, although microtubules composed of fewer or more protofilaments have been observed in vitro.[10]

Microtubules have a distinct polarity that is critical for their biological function. Tubulin polymerizes end to end, with the β-subunits of one tubulin dimer contacting the α-subunits of the next dimer. Therefore, in a protofilament, one end will have the α-subunits exposed while the other end will have the β-subunits exposed. These ends are designated the (−) and (+) ends, respectively. The protofilaments bundle parallel to one another with the same polarity, so, in a microtubule, there is one end, the (+) end, with only β-subunits exposed, while the other end, the (−) end, has only α-subunits exposed. While microtubule elongation can occur at both the (+) and (-) ends, it is significantly more rapid at the (+) end.[11]

The lateral association of the protofilaments generates a pseudo-helical structure, with one turn of the helix containing 13 tubulin dimers, each from a different protofilament. In the most common "13-3" architecture, the 13th tubulin dimer interacts with the next tubulin dimer with a vertical offset of 3 tubulin monomers due to the helicity of the turn. There are other alternative architectures, such as 11-3, 12-3, 14-3, 15-4, or 16-4 , that have been detected at a much lower occurrence.[12] Microtubules can also morph into other forms such as helical filaments, which are observed in protist organisms like foraminifera.[13] There are two distinct types of interactions that can occur between the subunits of lateral protofilaments within the microtubule called the A-type and B-type lattices. In the A-type lattice, the lateral associations of protofilaments occur between adjacent α and β-tubulin subunits (i.e. an α-tubulin subunit from one protofilament interacts with a β-tubulin subunit from an adjacent protofilament). In the B-type lattice, the α and β-tubulin subunits from one protofilament interact with the α and β-tubulin subunits from an adjacent protofilament, respectively. Experimental studies have shown that the B-type lattice is the primary arrangement within microtubules. However, in most microtubules there is a seam in which tubulin subunits interact α-β.[14]

Some species of Prosthecobacter also contain microtubules. The structure of these bacterial microtubules is similar to that of eukaryotic microtubules, consisting of a hollow tube of protofilaments assembled from heterodimers of bacterial tubulin A (BtubA) and bacterial tubulin B (BtubB). Both BtubA and BtubB share features of both α- and β-tubulin. Unlike eukaryotic microtubules, bacterial microtubules do not require chaperones to fold.[15] In contrast to the 13 protofilaments of eukaryotic microtubules, bacterial microtubules comprise only five.[1]

Intracellular organization

Microtubules are part of a structural network (the cytoskeleton) within the cell's cytoplasm. Roles of the microtubule cytoskeleton include mechanical support, organization of the cytoplasm, transport, motility and chromosome segregation. A microtubule is capable of growing and shrinking in order to generate force, and there are motor proteins that allow organelles and other cellular components to be carried along a microtubule. This combination of roles makes microtubules important for organizing and moving intracellular constituents.

The organization of microtubules in the cell is cell-type specific. In epithelia, the minus-ends of the microtubule polymer are anchored near the site of cell-cell contact and organized along the apical-basal axis. After nucleation, the minus-ends are released and then re-anchored in the periphery by factors such as ninein and Nezha/PLEKHA7.[16] In this manner, they can facilitate the transport of proteins, vesicles and organelles along the apical-basal axis of the cell. In fibroblasts and other mesenchymal cell-types, microtubules are anchored at the centrosome and radiate with their plus-ends outwards towards the cell periphery (as shown in the first figure). In these cells, the microtubules play important roles in cell migration. Moreover, the polarity of microtubules is acted upon by motor proteins, which organize many components of the cell, including the Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Golgi Apparatus.

Microtubule polymerization

Nucleation

Microtubules are typically nucleated and organized by dedicated organelles called microtubule-organizing centres (MTOCs). Contained within the MTOC is another type of tubulin, γ-tubulin, which is distinct from the α- and β-subunits of the microtubules themselves. The γ-tubulin combines with several other associated proteins to form a lock washer-like structure known as the "γ-tubulin ring complex" (γ-TuRC). This complex acts as a template for α/β-tubulin dimers to begin polymerization; it acts as a cap of the (−) end while microtubule growth continues away from the MTOC in the (+) direction.[17]

The centrosome is the primary MTOC of most cell types. However, microtubules can be nucleated from other sites as well. For example, cilia and flagella have MTOCs at their base termed basal bodies. In addition, work from the Kaverina group at Vanderbilt, as well as others, suggests that the Golgi apparatus can serve as an important platform for the nucleation of microtubules.[18] Because nucleation from the centrosome is inherently symmetrical, Golgi-associated microtubule nucleation may allow the cell to establish asymmetry in the microtubule network. In recent studies, the Vale group at UCSF identified the protein complex augmin as a critical factor for centrosome-dependent, spindle-based microtubule generation. It that has been shown to interact with γ-TuRC and increase microtubule density around the mitotic spindle origin.[19]

Some cell types, such as plant cells, do not contain well defined MTOCs. In these cells, microtubules are nucleated from discrete sites in the cytoplasm. Other cell types, such as trypanosomatid parasites, have a MTOC but it is permanently found at the base of a flagellum. Here, nucleation of microtubules for structural roles and for generation of the mitotic spindle is not from a canonical centriole-like MTOC.

Polymerization

Following the initial nucleation event, tubulin monomers must be added to the growing polymer. The process of adding or removing monomers depends on the concentration of αβ-tubulin dimers in solution in relation to the critical concentration, which is the steady state concentration of dimers at which there is no longer any net assembly or disassembly at the end of the microtubule. If the dimer concentration is greater than the critical concentration, the microtubule will polymerize and grow. If the concentration is less than the critical concentration, the length of the microtubule will decrease.[20]

Microtubule dynamics

Dynamic instability

Dynamic instability refers to the coexistence of assembly and disassembly at the ends of a microtubule. The microtubule can dynamically switch between growing and shrinking phases in this region.[21] Tubulin dimers can bind two molecules of GTP, one of which can be hydrolyzed subsequent to assembly. During polymerization, the tubulin dimers are in the GTP-bound state.[8] The GTP bound to α-tubulin is stable and it plays a structural function in this bound state. However, the GTP bound to β-tubulin may be hydrolyzed to GDP shortly after assembly. The assembly properties of GDP-tubulin are different from those of GTP-tubulin, as GDP-tubulin is more prone to depolymerization.[22] A GDP-bound tubulin subunit at the tip of a microtubule will tend to fall off, although a GDP-bound tubulin in the middle of a microtubule cannot spontaneously pop out of the polymer. Since tubulin adds onto the end of the microtubule in the GTP-bound state, a cap of GTP-bound tubulin is proposed to exist at the tip of the microtubule, protecting it from disassembly. When hydrolysis catches up to the tip of the microtubule, it begins a rapid depolymerization and shrinkage. This switch from growth to shrinking is called a catastrophe. GTP-bound tubulin can begin adding to the tip of the microtubule again, providing a new cap and protecting the microtubule from shrinking. This is referred to as "rescue".[23]

"Search and capture" model

In 1986, Marc Kirschner and Tim Mitchison proposed that microtubules use their dynamic properties of growth and shrinkage at their plus ends to probe the three dimensional space of the cell. Plus ends that encounter kinetochores or sites of polarity become captured and no longer display growth or shrinkage. In contrast to normal dynamic microtubules, which have a half-life of 5–10 minutes, the captured microtubules can last for hours. This idea is commonly known as the "search and capture" model.[24] Indeed, work since then has largely validated this idea. At the kinetochore, a variety of complexes have been shown to capture microtubule (+)-ends.[25] Moreover, a (+)-end capping activity for interphase microtubules has also been described.[26] This later activity is mediated by formins,[27] the adenomatous polyposis coli protein, and EB1,[28] a protein that tracks along the growing plus ends of microtubules.

Regulation of microtubule dynamics

Post-translational modifications

Although most microtubules have a half-life of 5-10 min, certain microtubules can remain stable for hours.[26] These stabilized microtubules accumulate post-translational modifications on their tubulin subunits by the action of microtubule-bound enzymes.[29][30] However, once the microtubule depolymerizes, most of these modifications are rapidly reversed by soluble enzymes. Since most modification reactions are slow while their reverse reactions are rapid, modified tubulin is only detected on long-lived stable microtubules. Most of these modifications occur on the C-terminal region of alpha-tubulin. This region, which is rich in negatively charged glutamate, forms relativey unstructured tails that project out from the microtubule and form contacts with motors. Thus, it is believed that tubulin modifications regulate the interaction of motors with the microtubule. Since these stable modified microtubules are typically oriented towards the site of cell polarity in interphase cells, this subset of modified microtubules provide a specialized route that helps deliver vesicles to these polarized zones. These modifications include:

- Detyrosination: the removal of the C-terminal tyrosine from alpha-tubulin. This reaction exposes a glutamate at the new C-terminus. As a result, microtubules that accumulate this modification are often referred to as Glu-microtubules. Although the tubulin carboxypeptidase has yet to be identified, the tubulin—tyrosine ligase (TTL) is known.[31]

- Delta2: the removal of the last two residues from the C-terminus of alpha-tubulin.[32] Unlike detyrosination, this reaction is thought to be irreversible and has only been documented in neurons.

- Acetylation: the addition of an acetyl group to lysine 40 of alpha-tubulin. This modification occurs on a lysine that is accessible only from the inside of the microtubule, and it remains unclear how enzymes access the lysine residue. The nature of the tubulin acetyltransferase remains controversial, but it has been found that in mammals the major acetyltransferase is ATAT1.[33] however, the reverse reaction is known to be catalyzed by HDAC6.[34]

- Polyglutamylation: the addition of a glutamate polymer (typically 4-6 residues long[35]) to the gamma-carboxyl group of any one of five glutamates found near the end of alpha-tubulin. Enzymes related to TTL add the initial branching glutamate (TTL4,5 and 7), while other enzymes that belong to the same family lengthen the polyglutamate chain (TTL6,11 and 13).[30]

- Polyglycylation: the addition of a glycine polymer (2-10 residues long) to the gamma-carboxyl group of any one of five glutamates found near the end of beta-tubulin. TTL3 and 8 add the initial branching glycine, while TTL10 lengthens the polyglycine chain.[30]

Tubulin is also known to be phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, sumoylated, and palmitoylated.[29]

Tubulin-binding drugs and chemical effects

A wide variety of drugs are able to bind to tubulin and modify its assembly properties. These drugs can have an effect at intracellular concentrations much lower than that of tubulin. This interference with microtubule dynamics can have the effect of stopping a cell’s cell cycle and can lead to programmed cell death or apoptosis. However, there are data to suggest that interference of microtubule dynamics is insufficient to block the cells undergoing mitosis.[36] These studies have demonstrated that suppression of dynamics occurs at concentrations lower than those needed to block mitosis. Suppression of microtubule dynamics by tubulin mutations or by drug treatment have been shown to inhibit cell migration.[37] Both microtubule stabilizers and destabilizers can suppress microtubule dynamics.

The drugs that can alter microtubule dynamics include:

- The cancer-fighting taxane class of drugs (paclitaxel (taxol) and docetaxel) block dynamic instability by stabilizing GDP-bound tubulin in the microtubule. Thus, even when hydrolysis of GTP reaches the tip of the microtubule, there is no depolymerization and the microtubule does not shrink back.

- The epothilones, e.g. Ixabepilone, work in a similar way to the taxanes.

- Nocodazole, vincristine, and colchicine have the opposite effect, blocking the polymerization of tubulin into microtubules.

- Eribulin binds to the (+) growing end of the microtubules. Eribulin exerts its anticancer effects by triggering apoptosis of cancer cells following prolonged and irreversible mitotic blockade.

Expression of β3-tubulin has been reported to alter cellular responses to drug-induced suppression of microtubule dynamics. In general the dynamics are normally suppressed by low, subtoxic concentrations of microtubule drugs that also inhibit cell migration. However, incorporating β3-tubulin into microtubules increases the concentration of drug that is needed to suppress dynamics and inhibit cell migration. Thus, tumors that express β3-tubulin are not only resistant to the cytotoxic effects of microtubule targeted drugs, but also to their ability to suppress tumor metastasis. Moreover, expression of β3-tubulin also counteracts the ability of these drugs to inhibit angiogenesis which is normally another important facet of their action.[38]

Microtubule polymers are extremely sensitive to various environmental effects. Very low levels of free calcium can destabilize microtubules and this prevented early researchers from studying the polymer in vitro.[8] Cold temperatures also cause rapid depolymerization of microtubules. In contrast, heavy water promotes microtubule polymer stability.[39]

Proteins that interact with microtubules

Microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs)

MAPs have been shown to play a crucial role in the regulation of microtubule dynamics in-vivo. The rates of microtubule polymerization, depolymerization, and catastrophe vary depending on which microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) are present. The originally identified MAPs from brain tissue can be classified into two groups based on their molecular weight. This first class comprises MAPs with a molecular weight below 55-62 kDa, and are called τ (tau) proteins. In-vitro, tau proteins have been shown to directly bind microtubules, promote nucleation and prevent disassembly, and to induce the formation of parallel arrays.[40] Additionally, tau proteins have also been shown to stabilize microtubules in axons and have been implicated in Alzheimer's disease.[41] The second class is composed of MAPs with a molecular weight of 200-1000 kDa, of which there are four known types: MAP-1, MAP-2, MAP-3 and MAP-4. MAP-1 proteins consists of a set of three different proteins: A, B and C. The C protein plays an important role in the retrograde transport of vesicles and is also known as cytoplasmic dynein. MAP-2 proteins are located in the dendrites and in the body of neurons, where they bind with other cytoskeletal filaments. The MAP-4 proteins are found in the majority of cells and stabilize microtubules. In addition to MAPs that have a stabilizing effect on microtubule structure, other MAPs can have a destabilizing effect either by cleaving or by inducing depolymerization of microtubules. Three proteins called katanin, spastin, and fidgetin have been observed to regulate the number and length of microtubules via their destabilizing activities.

Plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs)

Plus end tracking proteins are MAP proteins which bind to the tips of growing microtubules and play an important role in regulating microtubule dynamics. For example, +TIPs have been observed to participate in the interactions of microtubules with chromosomes during mitosis. The first MAP to be identified as a +TIP was CLIP170 (cytoplasmic linker protein), which has been shown to play a role in microtubule depolymerization rescue events. Additional examples of +TIPs include EB1, EB2, EB3, p150Glued, Dynamitin, Lis1, CLIP115, CLASP1, and CLASP2.

Motor proteins

Microtubules can act as substrates for motor proteins that are involved in important cellular functions such as vesicle trafficking and cell division. Unlike other microtubule-associated proteins, motor proteins utilize the energy from ATP hydrolysis to generate mechanical work that moves the protein along the substrate. The major motor proteins that interact with microtubules are kinesin, which usually moves toward the (+) end of the microtubule, and dynein, which moves toward the (−) end.

- Dynein is composed of two identical heavy chains, which make up two large globular head domains, and a variable number of intermediate and light chains. Dynein-mediated transport takes place from the (+) end towards the (-) end of the microtubule. ATP hydrolysis occurs in the globular head domains, which share similarities with the AAA+ (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) protein family. ATP hydolysis in these domains is coupled to movement along the microtubule via the microtubule-binding domains. Dynein transports vesicles and organelles throughout the cytoplasm. In order to do this, dynein molecules bind organelle membranes via a protein complex that contains a number of elements including dynactin.

- Kinesin has a similar structure to dynein. Kinesin is involved in the transport of a variety of intracellular cargoes, including vesicles, organelles, protein complexes, and mRNAs toward the microtubule's (+) end.[42]

Some viruses (including retroviruses, herpesviruses, parvoviruses, and adenoviruses) that require access to the nucleus to replicate their genomes attach to motor proteins.

Functions

Cell migration

Microtubule plus ends are often localized to particular structures. In polarized interphase cells, microtubules are disproportionately oriented from the MTOC toward the site of polarity, such as the leading edge of migrating fibroblasts. This configuration is thought to help deliver microtubule-bound vesicles from the Golgi to the site of polarity.

Dynamic instability of microtubules is also required for the migration of most mammalian cells that crawl.[43] Dynamic microtubules regulate the levels of key G-proteins such as RhoA[44] and Rac1,[45] which regulate cell contractility and cell spreading. Dynamic microtubules are also required to trigger focal adhesion disassembly, which is necessary for migration.[46]

Mitosis

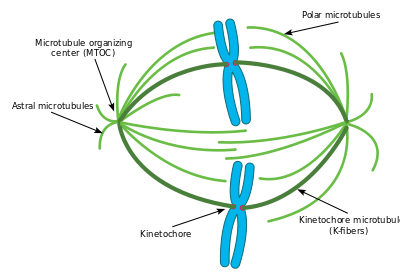

A notable structure composed largely of microtubules is the mitotic spindle, used by eukaryotic cells to segregate their chromosomes during cell division. The mitotic spindle includes the spindle microtubules, microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), and the MTOC. The microtubules originate in the MTOC and fan out into the cell; each cell has two MTOCs, as shown in the diagram.

The process of mitosis is facilitated by three main subgroups of microtubules, known as astral, polar, and kinetochore microtubules. An astral microtubule is a microtubule originating from the MTOC that does not connect to a chromosome. Astral microtubules instead interact with the cytoskeleton near the cell membrane and function in concert with specialized dynein motors. Dynein motors pull the MTOC toward the cell membrane, thus assisting in correct positioning and orientation of the entire apparatus.

Kinetochore microtubules directly connect to the chromosomes, at the kinetochores. To clarify the terminology, each chromosome has two chromatids, and each chromatid has a kinetochore. The two kinetochores associated with a region of the chromosome called the centromere. The polar microtubules from one MTOC intertwine with the microtubules from the other MTOC; motor proteins make them push against each other and assist in the separation of the chromosomes to the two daughter cells.

Cell division in a typical eukaryote finishes with the generation of a final cytoplasmic bridge between the two daughter cells termed the midbody. This structure is built of microtubules that originally made up part of the mitotic spindle.

Cilia and flagella

Microtubules have a major structural role in eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Cilia and flagella always extend directly from a MTOC, in this case termed the basal body. The action of the dynein motor proteins on the various microtubule strands that run along a cilium or flagellum allows the organelle to bend and generate force for swimming, moving extracellular material, and other roles. Prokaryotes possess tubulin-like proteins including FtsZ. However, prokaryotic flagella are entirely different in structure from eukaryotic flagella and do not contain microtubule-based structures.

Development

The cytoskeleton formed by microtubules is essential to the morphogenetic process of an organism’s development. For example, a network of polarized microtubules is required within the oocyte of Drosophila melanogaster during its embryogenesis in order to establish the axis of the egg. Signals sent between the follicular cells and the oocyte (such as factors similar to epidermal growth factor) cause the reorganization of the microtubules so that their (-) ends are located in the lower part of the oocyte, polarizing the structure and leading to the appearance of an anterior-posterior axis.[47] This involvement in the body’s architecture is also seen in mammals.[48]

Another area where microtubules are essential is the formation of the nervous system in higher vertebrates, where tubulin’s dynamics and those of the associated proteins (such as the MAPs) is finely controlled during the development of the nervous system.[49]

Gene regulation

The cellular cytoskeleton is a dynamic system that functions on many different levels: In addition to giving the cell a particular form and supporting the transport of vesicles and organelles, it can also influence gene expression. However, the signal transduction mechanisms involved in this communication are little understood. Notwithstanding this, the relationship between the drug-mediated depolymerization of microtubules and the specific expression of transcription factors has been described, which has provided information on the differential expression of the genes depending on the presence of these factors.[50] This communication between the cytoskeleton and the regulation of the cellular response is also related to the action of growth factors: for example, this relation exists for connective tissue growth factor.[51]

See also

- Intermediate filament

- Microfilament

- Orchestrated objective reduction – a hypothesis explaining consciousness

References

- 1 2 Pilhofer, Martin; Ladinsky, Mark S.; McDowall, Alasdair W.; Petroni, Giulio; Jensen, Grant J. (2011-12-01). "Microtubules in bacteria: Ancient tubulins build a five-protofilament homolog of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton". PLOS Biology. 9 (12): e1001213. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001213. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 3232192

. PMID 22162949.

. PMID 22162949. - ↑ https://www.rpi.edu/dept/bcbp/molbiochem/MBWeb/mb2/part1/microtub.htm

- ↑ Vale RD (Feb 2003). "The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport.". Cell. 112 (4): 467–80. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00111-9. PMID 12600311.

- ↑ Howard J; Hyman AA (Feb 2007). "Microtubule polymerases and depolymerases.". Curr Opin Cell Biol. 19 (1): 31–5. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2006.12.009.

- ↑ Jiang S, Narita A, Popp D, Ghoshdastider U, Lee LJ, Srinivasan R, Balasubramanian MK, Oda T, Koh F, Larsson M, Robinson RC (2016). "Novel actin filaments from Bacillus thuringiensis form nanotubules for plasmid DNA segregation.". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113 (9): E1200–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1600129113. PMC 4780641

. PMID 26873105.

. PMID 26873105. - ↑ Wayne, R. 2009. Plant Cell Biology: From Astronomy to Zoology. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press, p. 165.

- ↑ WJ Löwe; H Li; K.H Downing; E Nogales (2001). "Refined structure of αβ-tubulin at 3.5 Å resolution". J. Mol Biol. 313 (5): 1045–57. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. PMID 11700061.

- 1 2 3 Weisenberg RC (1972). "Microtubule formation in vitro in solutions containing low calcium concentrations". Science. 177: 1104–5. doi:10.1126/science.177.4054.1104.

- ↑ Desai A. & Mitchison TJ (1997). "Microtubule polymerization dynamics.". Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 13: 83–117. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. PMID 9442869.

- ↑ Chrétien D, Metoz F, Verde F, Karsenti E, Wade RH. Lattice defects in microtubules: protofilament numbers vary within individual microtubules J Cell Biol. 1992 Jun;117(5):1031-40.

- ↑ Walker RA, O'Brien ET, Pryer NK, Soboeiro MF, Voter WA, et al. (1988). "Dynamic instability of individual microtubules analysed by video light microscopy: rate constants and transition frequencies". J. Cell Biol. 107: 1437–48. doi:10.1083/jcb.107.4.1437.

- ↑ Sui H, Downing, K (2010). "Structural basis of interprotofilament interaction and lateral deformation of microtubules". Structure. 18: 1022–1031. doi:10.1016/j.str.2010.05.010.

- ↑ Bassen DM, Hou Y, Bowser SS, Banavali NK (2016). "Maintenance of electrostatic stabilization in altered tubulin lateral contacts may facilitate formation of helical filaments in foraminifera". Scientific Reports. 6: 31723. doi:10.1038/srep31723.

- ↑ Nogales E (2000). "Structural Insights into Microtubule Function". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 69: 277–302. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.277.

- ↑ Schlieper, Daniel; Oliva, María A.; Andreu, José M.; Löwe, Jan (2005-06-28). "Structure of bacterial tubulin BtubA/B: Evidence for horizontal gene transfer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (26): 9170–9175. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502859102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1166614

. PMID 15967998.

. PMID 15967998. - ↑ Bartolini, F; Gundersen, G. G. (2006). "Generation of noncentrosomal microtubule arrays". Journal of Cell Science. 119 (Pt 20): 4155–63. doi:10.1242/jcs.03227. PMID 17038542.

- ↑ Desai A. & Mitchison TJ (1997). "Microtubule polymerization dynamics.". Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 13: 83–117. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. PMID 9442869.

- ↑ Vinogradova, T; Miller, P. M.; Kaverina, I (2009). "Microtubule network asymmetry in motile cells: Role of Golgi-derived array". Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex.). 8 (14): 2168–74. doi:10.4161/cc.8.14.9074. PMC 3163838

. PMID 19556895.

. PMID 19556895. - ↑ Ryota Uehara et al.; (2009). "The augmin complex plays a critical role in spindle microtubule generation for mitotic progression and cytokinesis in human cells". Prot Natl Acad Sci. 106: 6998–7003. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901587106. PMC 2668966

. PMID 19369198.

. PMID 19369198. - ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. The Self-Assembly and Dynamic Structure of Cytoskeletal Filaments. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26862/

- ↑ Karp, Gerald (2005). Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments. USA: John Wiley & Sons. p. 355. ISBN 0-471-46580-1.

- ↑ Weisenberg RC, Deery WJ, Dickinson PJ (September 1976). "Tubulin-nucleotide interactions during the polymerization and depolymerization of microtubules". Biochemistry. 15 (19): 4248–54. doi:10.1021/bi00664a018. PMID 963034.

- ↑ Mitchison T, Kirschner M (1984). "Dynamic instability of microtubule growth". Nature. 312 (5991): 237–42. doi:10.1038/312237a0. PMID 6504138.

- ↑ Kirschner M, Mitchison T (May 1986). "Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis". Cell. 45 (3): 329–42. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90318-1. PMID 3516413.

- ↑ Cheeseman IM, Desai A (January 2008). "Molecular architecture of the kinetochore-microtubule interface". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 9 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1038/nrm2310. PMID 18097444.

- 1 2 Infante AS, Stein MS, Zhai Y, Borisy GG, Gundersen GG (November 2000). "Detyrosinated (Glu) microtubules are stabilized by an ATP-sensitive plus-end cap". Journal of Cell Science. 113 (22): 3907–19. PMID 11058078.

- ↑ Palazzo AF, Cook TA, Alberts AS, Gundersen GG (August 2001). "mDia mediates Rho-regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules". Nature Cell Biology. 3 (8): 723–9. doi:10.1038/35087035. PMID 11483957.

- ↑ Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, et al. (September 2004). "EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (9): 820–30. doi:10.1038/ncb1160. PMID 15311282.

- 1 2 Janke C, Bulinski JC (December 2011). "Post-translational regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: mechanisms and functions". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (12): 773–86. doi:10.1038/nrm3227. PMID 22086369.

- 1 2 3 Garnham CP, Roll-Mecak A (July 2012). "The chemical complexity of cellular microtubules: tubulin post-translational modification enzymes and their roles in tuning microtubule functions". Cytoskeleton. 69 (7): 442–63. doi:10.1002/cm.21027. PMC 3459347

. PMID 22422711.

. PMID 22422711. - ↑ Ersfeld K, Wehland J, Plessmann U, Dodemont H, Gerke V, Weber K (February 1993). "Characterization of the tubulin-tyrosine ligase". The Journal of Cell Biology. 120 (3): 725–32. doi:10.1083/jcb.120.3.725. PMC 2119537

. PMID 8093886.

. PMID 8093886. - ↑ Paturle-Lafanechère L, Eddé B, Denoulet P, et al. (October 1991). "Characterization of a major brain tubulin variant which cannot be tyrosinated". Biochemistry. 30 (43): 10523–8. doi:10.1021/bi00107a022. PMID 1931974.

- ↑ Kalebic, Nereo; Sorrentino, Simona; Perlas, Emerald; Bolasco, Giulia; Martinez, Concepcion; Heppenstall, Paul A. (2013-06-10). "αTAT1 is the major α-tubulin acetyltransferase in mice". Nature Communications. 4. doi:10.1038/ncomms2962. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ↑ Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, et al. (May 2002). "HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase". Nature. 417 (6887): 455–8. doi:10.1038/417455a. PMID 12024216.

- ↑ Audebert S, Desbruyères E, Gruszczynski C, et al. (June 1993). "Reversible polyglutamylation of alpha- and beta-tubulin and microtubule dynamics in mouse brain neurons". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4 (6): 615–26. doi:10.1091/mbc.4.6.615. PMC 300968

. PMID 8104053.

. PMID 8104053. - ↑ Ganguly, A; Yang, H; Cabral, F (2010). "Paclitaxel-dependent cell lines reveal a novel drug activity". Molecular cancer therapeutics. 9 (11): 2914–23. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0552. PMC 2978777

. PMID 20978163.

. PMID 20978163. - ↑ Yang, Hailing; Ganguly, Anutosh; Cabral, Fernando (2010). "Inhibition of Cell Migration and Cell Division Correlates with Distinct Effects of Microtubule Inhibiting Drugs". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (42): 32242–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.160820. PMC 2952225

. PMID 20696757.

. PMID 20696757. - ↑ Ganguly, A; Yang, H; Cabral, F (2011). "Class III β-tubulin counteracts the ability of paclitaxel to inhibit cell migration.". Oncotarget. 2 (5): 368–377. PMC 3248193

. PMID 21576762.

. PMID 21576762. - ↑ Burgess, J; Northcote, DH (1969). "Action of colchicine and heavy water on the polymerization of microtubules in wheat root meristem.". J Cell Sci. 5 (2): 433–451. PMID 5362335.

- ↑ Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM (February 1995). "Microtubules and microtubule-associated proteins". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7 (1): 72–81. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(95)80047-6. PMID 7755992.

- ↑ Gregory T. Bramblett; et al. (June 1993). "Abnormal tau phosphorylation at Ser396 in alzheimer's disease recapitulates development and contributes to reduced microtubule binding". Neuron. 10 (6): 1089–1099. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90057-X.

- ↑ Hirowaka N; et. al. (Oct 2009). "Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport". Nature Reviews. 10: 682–696. doi:10.1038/nrm2774. PMID 19773780.

- ↑ Mikhailov, A.; Gundersen, G.G. (1998). "Relationship between microtubule dynamics and lamellipodium formation revealed by direct imaging of microtubules in cells treated with nocodazole or taxol". Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 41 (4): 325–340. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)41:4<325::AID-CM5>3.0.CO;2-D. ISSN 0886-1544.

- ↑ Ren, X.-D. (1999). "Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton". The EMBO Journal. 18 (3): 578–585. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.3.578. ISSN 1460-2075.

- ↑ Waterman-Storer, Clare M.; Worthylake, Rebecca A.; Liu, Betty P.; Burridge, Keith; Salmon, E.D. (1999). "Microtubule growth activates Rac1 to promote lamellipodial protrusion in fibroblasts". Nature Cell Biology. 1 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1038/9018. ISSN 1465-7392.

- ↑ Ezratty, E. J.; Partridge, M. A.; Gundersen, G. G. (2005). "Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly is mediated by dynamin and focal adhesion kinase". Nature Cell Biology. 7 (6): 581–90. doi:10.1038/ncb1262. PMID 15895076.

- ↑ van Eeden F, St Johnston D (August 1999). "The polarisation of the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes during Drosophila oogenesis". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 9 (4): 396–404. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80060-4. PMID 10449356.

- ↑ Beddington RS, Robertson EJ (January 1999). "Axis development and early asymmetry in mammals". Cell. 96 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80560-7. PMID 9988215.

- ↑ Tucker RP (1990). "The roles of microtubule-associated proteins in brain morphogenesis: a review". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 15 (2): 101–20. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(90)90013-E. PMID 2282447.

- ↑ Rosette C, Karin M (March 1995). "Cytoskeletal control of gene expression: depolymerization of microtubules activates NF-kappa B". The Journal of Cell Biology. 128 (6): 1111–9. doi:10.1083/jcb.128.6.1111. PMC 2120413

. PMID 7896875.

. PMID 7896875. - ↑ Ott C, Iwanciw D, Graness A, Giehl K, Goppelt-Struebe M (November 2003). "Modulation of the expression of connective tissue growth factor by alterations of the cytoskeleton". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (45): 44305–11. doi:10.1074/jbc.M309140200. PMID 12951326.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Microtubules. |