Megaladapis

| Megaladapis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Megaladapis edwardsi | |

| Extinct (1280–1420 CE) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | †Megaladapidae |

| Genus: | †Megaladapis Forsyth Major, 1894[1] |

| Species | |

|

Subgenus Peloriadapis

Subgenus Megaladapis

| |

Megaladapis, informally known as koala lemur,[1][2] is an extinct genus belonging to the family Megaladapidae, consisting of three extinct species of lemurs that once inhabited the island of Madagascar. The largest measured between 1.3 to 1.5 m (4 to 5 ft) in length.

Adaptations

Megaladapis was quite different from any living lemur. Its body was squat and built like that of the modern koala. Its long arms, fingers, feet, and toes were specialized for grasping trees, and its legs were splayed for vertical climbing. The hands and feet were curved and the ankles and wrists did not have the usual stability needed to travel on the ground that most other Lemurids have.[3] Megaladapis is perfectly evolved to live in an arboreal environment by its pedal morphology. Its foot have large hallux and lateral abducctor musculature that helps it grasping vertically on the trees. In other species which is adepted in an arboreal environment can also found the similar pedal design.[4] Its head was unlike any other primates, most strikingly, its eyes were on the sides of its skull, instead of forward on the skull like all other primates.

Its long canine teeth and a cow-like jaw formed a tapering snout. Its jaw muscles were powerful for chewing the tough native vegetation. Megaladapis is suggested to have been survived on a folivorous diet, using a leaf-cropping foraging method, based upon the microwear patterns of its teeth. These patterns found no permanent upper incisors or the presence of an expanded articular facet on the posterior face of the mandibular condyle. This diet and similar phenotypic traits of the teeth are the basis for concluding a shared ancestry with the Lepilemur.[5] The diet, however, might be the factor that influences the dental development. Species with a larger brain, later initiation of molar crowns, and longer formation of crown are considered to have more of an omnivorous diet. In contrast, Megaladapis is on a folivorous diet, despite having a smaller brain, early initiation of molar crowns, and fast crown formation.[6]

Its body weight reached 50 kilograms (110 lb). The shape of its skull was unique among all known primates, with a nasal region which showed similarities to those of rhinoceros, what was probably a feature combined with an enlarged upper lip for grasping leaves. Its body size was the largest among other lemurs. Compared to the next extinct lemur, Megaladapis had double their mass. However, its brain was small, compared to other lemurs, shown by its mass to brain size ratio.[6] An endocast of the skull was taken and it was found that the brain capacity was about 250cc. This is about 3 to 4 times the size of a common cat's.[7] Compared to the size of the skull, the diameter of the orbits protrudes in a tabular form outwards and forwards, suggesting that the Megaladapis was diurnal.[8] The gestation length of Megaladais is approximately 198 days at the minimum. It is more likely longer than that. It is calculated by the time when initiation of molar crown occurred. The later of crown initiation occurred, the longer the length of gestation if it occurred after three months.[6]

Megaladapis evolved because the island's topography was always changing. Along with the other lemurs, Megaladapis specialized within its own niche. The general expectations of tree climbers such as Megaladapis is that with an increase in size, the body's forelimbs will also increase proportionally.[9]

Some exterior scratches and incisions were found on both its metatarsus and its mandibula. These cuts found on the metatarsus are comparable to those found in caves and considered to be produced by humans, while those found on the mandibula seem to have been produced by some instrument engineered for cutting – indications that the Megalapadis was at some point in direct contact with the anatomically-modern humans of its time.[8]

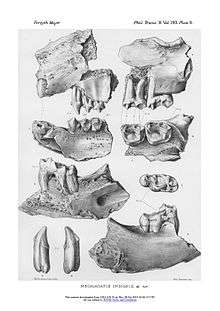

There are several fragments of the upper and lower jaw preserved in a beautiful state. The upper molars of Lepidolemur is very close in shape to the fossil of Megaladapis. The main difference between Megaladapis and Lepidolemur is that the outer crown-surface of Lepidolemur’s molars forms nearly a straight line, almost parallel with the long axis of the skull, and the outer side is slightly concave inwards. The antero-internal cingulum is missing in the molars of Lepidolemur.[7]

It is hard to say about the anterior parts of the dentition, the canines and incisors. The bulle osseve are broken away, the foremost facial portion and base of the skull is also wanting, The length of the whole skull may be approximately calculated at 250 millims, the size is about from three to four times of a common Cat. According to worn condition of the teeth, the obliteration of most of the sutures of the very thick bones, and the strongly developed crests, it is shown that the individual was much aged.[10]

Cultural references

It is often believed that Malagasy legends of the tretretretre or tratratratra, an extinct animal, refer to Megaladapis, but the details of these tales, notably the "human-like" face of the animal, match the related Palaeopropithecus much better.[11]

Extinction

When humans arrived on Madagascar 2,300 years ago, in addition to the species that are still alive today, there were at least 17 species of now-extinct "giant" lemur among the mammals living there, which included the Megaladapis. The landscape in which giant lemurs were found were largely forested areas with dense vegetation. Almost directly after human arrival, there was a rapid decline in the spores of Sporormiella which indicates a decrease in megafaunal biomass. Charcoal microparticles being found in surveys of various areas in Madagascar give evidence to the fact that human habitat modification only occurred after this decline in megafaunal biomass. Charcoal deposits provide evidence to the fact that humans used fire to clear large pieces of land very rapidly. The habitats that Megaladapis once were very well adapted to turned into grasslands, which provided little to no cover from outside forces for these creatures. Thus, the scientific conclusion arrived upon is one that hypothesizes that "giant" lemur populations, like the Megaladapis, were on the decline due to habitat fragmentation, and human activities (for example, clearing of land through "slash-and-burn" techniques) were the final push to extinction for these lemurs between 500 and 600 years ago.[12]

Over-hunting by humans was also deemed a major contributor to the extinction of "giant" lemurs. Minor droughts are frequent in Madagascar, but a major drought approximately 1000 years ago significantly lowered lake levels, caused a severe vegetation transition, and caused fires to spark in fire-prone grasslands and savannas. Crop failures due to these conditions would drive inhabitants to hunt for bushmeat to survive, and these giant lemurs were an easy source of said meat.[13]

Megaladapis were slow-moving, bulky creatures that were diurnal, or active during the day. Lemurs in general also had small group sizes and were highly seasonal breeders ( (they breed for about one to two weeks a year).[14] These features already put them at an evolutionary disadvantage; Megaladapis (along with the other species of giant lemur) were more susceptible to predators (humans more specifically), forest fires, and habitat destruction due to these traits.[15] The low breeding rates also made recovery from devastating loss of life among the species very difficult to recover from, as evidenced by the eventual extinction of Megaladapis.[14]

Gallery

| Images of Megaladapis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- 1 2 Mittermeier, Russell A.; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). Conservation International. pp. 46–49. ISBN 1-881173-88-7.

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Primates of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0-8018-6251-5.

- ↑ Spoor, F; Garland Jr, T; Krovitz, G; Ryan, T. M.; Silcox, M. T.; Walker, A (2007). "The primate semicircular canal system and locomotion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (26): 10808–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704250104. PMC 1892787

. PMID 17576932.

. PMID 17576932. - ↑ Wunderlich, R. E.; Simons, E. L.; Jungers, W. L. (May 1996). "New pedal remains of Megaladapis and their functional significance". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 100 (1): 115–39. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199605)100:1<115::AID-AJPA11>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 8859959.

- ↑ Perry, G.H., Orlando, L. (1 February 2015). "Ancient DNA and human evolution". Journal of Human Evolution. 79: 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.12.002. PMID 25619123.

- 1 2 3 Schwartz, G.T (2007). "Inferring primate growth, development and life history from dental microstructure: The case of the extinct Malagasy lemur, Megaladapis". Dental Perspectives on Human Evolution: State of the Art Research in Dental Paleoanthropology. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Netherlands: Springer. p. 147. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5845-5_10. ISBN 978-1-4020-5844-8.

- 1 2 Major, C. I. F. (1894). "On Megaladapis madagascariensis, an Extinct Gigantic Lemuroid from Madagascar; with Remarks on the Associated Fauna, and on Its Geological Age". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 185: 15–38. doi:10.1098/rstb.1894.0002. JSTOR 91769.

- 1 2 Major, Forsyth (January 1, 1900). "Extinct Mammalia from Madagascar. I. Megaladapis insignis" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 193 (185–193): 47–50. doi:10.1098/rstb.1900.0009. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ↑ Jungers, W. L. (1980). "Adaptive diversity in subfossil Malagasy prosimians". Zeitschrift fur Morphologie und Anthropologie. 71 (2): 177–86. JSTOR 25756477. PMID 6776705.

- 1 2 Major, C. I. F. (1900). "Extinct Mammalia from Madagascar. I. Megaladapis insignis, sp. N". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 193 (185–193): 47–50. doi:10.1098/rstb.1900.0009. JSTOR 91919.

- ↑ Simons, E. L. (2003). "Chapter 6: Lemurs: Old and New". In Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P. Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 142–166. ISBN 0-226-30306-3.

- ↑ Muldoon, Kathleen M. (2010-04-01). "Paleoenvironment of Ankilitelo Cave (late Holocene, southwestern Madagascar): implications for the extinction of giant lemurs". Journal of Human Evolution. 58 (4): 338–352. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.01.005. PMID 20226497.

- ↑ Virah-Sawmy, Malika; Willis, Katherine J.; Gillson, Lindsey (2010). "Evidence for drought and forest declines during the recent megafaunal extinctions in Madagascar". Journal of Biogeography. 37 (3): 506–519. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02203.x.

- 1 2 Scott, Rob. "The Lost Lemurs: Extinction in Madagascar." Rutgers University. Hickman Hall, New Brunswick, NJ. n.d. Lecture.

- ↑ Culotta, Elizabeth (1995). "Many Suspects to Blame in Madagascar Extinctions". Science. 268 (5217): 1568–1569. doi:10.1126/science.268.5217.1568. PMID 17754597.