Mauryan art

Mauryan art encompasses the arts produced during the period of the Mauryan Empire (4th to 2nd century BCE), which was the first empire to rule over most of the Indian subcontinent. It represented an important transition in Indian art from use of wood to stone. It was a royal art patronized by Mauryan kings especially Ashoka. Pillars, Stupas, caves are the most prominent examples.

Overview

According to Niharranjan Ray, the sum total of the Mauryan treasury of art include the remains of the royal palace and the city of Pataliputra, a monolithic rail at Sarnath, the Bodhimandala or the altar resting on four pilars at Bodhgaya, the excavated Chaitya-halls in the Barabar and Nagarjuni hills of Gaya including the Sudama cave bearing the inscription dated the 12th regnal year of Ashoka, the non-edict bearing and edict bearing pillars, the animal sculptures crowning the pillars with animal and vegetal reliefs decorating the abaci of the capitals and the front half of the representation of an elephant carved out in the round from a live rock at Dhauli.[1]

Coomaraswmy argued that the Mauryan art may be said to exhibit three main phases. The first phase was the continuation of the Pre-Mauryan tradition, which is found in some instances to the representation of the Vedic deities (the most significant examples are the reliefs of Surya and Indra at the Bhaja Caves.) The second phase was the court art of Ashoka, typically found in the monolithic columns on which his edicts are inscribed and the third phase was the beginning of brick and stone architecture, as in the case of the original stupa at Sanchi, the small monolithic rail at Sanchi and the Lomash Rishi cave in the Barabar Caves, with its ornamentated facade, reproducing the forms of wooden structure.[2]

Architecture

While the period marked a second transition to use of brick and stone, wood was still the material of choice. Kautilya in the Arthashastra advises the use of brick and stone for their durability. Yet he devotes a large section to safeguards to be taken against conflagrations in wooden buildings indicating their popularity.

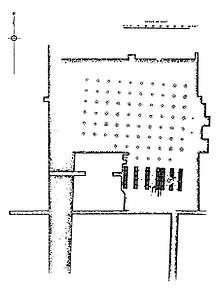

Megasthenes mentions that the capital city of Pataliputra was encircled by a massive timber-palisade, pierced by loopholes through which archers could shoot. It had sixty-four gates and 570 towers.[3] According to Strabo, the gilded pillars of the palace were adorned with golden vines and silver birds. The palace stood in an extensive park studded with fish ponds. It was furnished with a great variety of ornamental trees and shrubs. Excavations carried out by Spooner and Waddell have brought to light remains of huge wooden palisades at Bulandi Bagh in Pataliputra. The remains of one of the buildings, an 80 pillared hall at Kumrahar are of particular significance. Out of 80 stone columns, that once stood on a wooden platform and supported a wooden roof, Spooner was able to discover the entire lower part of at least one in almost perfect conditions. It is more or less similar to an Ashokan pillar, smooth, polished and made of grey Chunar sandstone.[4]

Many stupas like those at Sanchi, Sarnath and probably Amaravati were originally built as brick and masonry mounds during the reign of Ashoka. Unfortunately they were renovated many times, which leaves us with hardly a clue of the original structures.

Sculpture

This period marked an imaginative and impressive step forward in Indian stone sculpture; much previous sculpture was probably in wood and has not survived. The elaborately carved animal capitals surviving on from some Pillars of Ashoka are the best known works, and among the finest, above all the Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath that is now the National Emblem of India. Coomaraswamy distinguishes between court art and a more popular art during the Mauryan period. Court art is represented by the pillars and their capitals. Popular art is represented by the works of the local sculptors like chauri (whisk)-bearer from Didarganj.[5]

Pillars and their capitals

The Pataliputra capital, dated to the 3rd century BC, has been excavated at the Mauryan city of Pataliputra. It has been described as Perso-Iionic, with a strong Greek stylistic influence, including volute, bead and reel, meander or honeysuckle designs. This monumental piece of architecture tends to suggest the Achaemenid and Hellenistic artistic influence at the Mauryan court from early on.[6]

Emperor Ashoka also erected religious pillars throughout India. These pillars were carved in two types of stone. Some were of the spotted red and white sandstone from the region of Mathura, the others of buff-coloured fine grained hard sandstone usually with small black spots quarried in the Chunar near Varanasi. The uniformity of style in the pillar capitals suggests that they were all sculpted by craftsmen from the same region. It would therefore seem, that stone transported from Mathura and Chunar to the various sites where the pillars have been found and here the stone was cut and carved by craftsmen[5] They were given a fine polish characteristic of Mauryan sculpture. These pillars were mainly erected in the Gangetic plains. They were inscribed with edicts of Ashoka on Dhamma or righteousness. The animal capital as a finely carved lifelike representation, noteworthy are the lion capital of Sarnath, the bull capital of Rampurva and the lion capital of Lauria Nandangarh. Much speculation has been made about the similarity between these capitals and Achaemenid works.

Examples of popular art

The work of local sculptors illustrates the popular art of the Mauryan period. This consisted of sculpture which probably was not commissioned by the emperor. The patrons of the popular art were the local governors and the more well-to-do subjects. It is represented by figures such as the female figure of Besnagar, the male figure of Parkham and the whisk-bearer from Didarganj (although its age is debated). Technically they are fashioned with less skill than the pillar capitals. They express a considerable earthiness and physical vitality.[5]

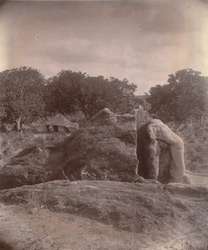

The stone elephant at Dhauli was also probably carved by local craftsmen and not by the special craftsmen who were responsible for the animal capitals. The image of the elephant emerging from the rock is a most impressive one, and its purpose was probably to draw attention to the inscription nearby.[5]

Terracotta objects of various sizes have been found at Mauryan sites. A continuation of the tradition of making mother-goddesses in clay, which dates back to the prehistoric period is revealed by the discovery of these objects at Mauryan levels during the excavations at Ahicchatra. They are found more commonly from Pataliputra to Taxila. Many have stylized forms and technically they are more accomplished, in that they have a well-defined shape and clear ornamenation. Some appear to have been made from moulds, yet there is little duplication. Terracotas from Taxila consists of primitive idols, votive reliefs with deities, toys dice, ornaments and beads. Among the ornaments were round medallions, similar to the bullae worn by Roman boys.[5] Ringstones probably associated with a fertility cult have also been found in some quantity. Terracotta images of folk gods and goddesses which have been found having an earthy charm.

Pottery

Use of the potters wheel became universal. The pottery associated with the Mauryan period consists of many types of ware. But the most highly developed technique is seen in a special type of pottery known as the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBP), which was the hallmark of the preceding and early Mauryan periods. The NBP ware is made of finely levigated alluvial clay, which when seen in section is usually of a grey and sometimes of a red hue. It has a brilliantly burnished dressing of the quality of a glaze which ranges from a jet black to a deep grey or a metallic steel blue. Occasionally small red-brown patches are apparent on the surface. It can be distinguished from other polished or graphite-coated red wares by its peculiar lustre and brilliance. This ware was used largely for dishes and small bowls. It is found in abundance in the Ganges valley. Although NBP was not very rare, it was obviously a more expensive ware than the other varieties, since potsherds of NBP were occasionally found riveted with copper pins indicating that even a cracked vessel in NBP ware had its value.[8]

Coins

The coins issued by the Mauryans are mostly silver and a few copper pieces of metal in various shapes, sizes and weights and which have one or more symbols punched on them. The most common symbols are the elephant, the tree in railing symbol and the mountain. The technique of producing such coins was generally that the metal was cut first and then the device was punched.[8] These symbols are said to have either represented the Royal insignia or the symbol of the local guild that struck the coin. Some coins had Shroff (money changer) marks on them indicating that older coins were often re-issued. The alloy content closely resembles that specified in the Arthashastra. Based on his identification of the symbols on the punch-marked coins with certain Mauryan rulers, Kosambi argued that the Mauryan punch-marked Karshapana after Chandragupta has the same weight as its predecessor, but much more copper, cruder fabric, and such a large variation in weight that the manufacture must have been hasty. This evidence of stress and unsatisfied currency demand is accompanied by debasement (inflation) plus vanishing of the reverse marks which denoted the ancient trade guilds.[9] This in his opinion indicated that there was a fiscal crisis in the later Mauryan period. However his method of analysis and the chronological identification has been questioned.[10]

Painting

While we can be sure of Mauryan proficiency in this field based on the descriptions of Megasthenes, unfortunately no proper representative has been found to date. Many centuries later, the paintings of the Ajanta Caves, the oldest significant body of Indian painting, show there was a well-developed tradition, which may well stretch back to Mauryan times.

Gallery

- Female terracotta figure, northern India, c. 320-200 BCE

Head from Sarnath,

Head from Sarnath, Head of an Indian Village Deity, terracotta, 3rd century BCE

Head of an Indian Village Deity, terracotta, 3rd century BCE

2nd-century statuette

2nd-century statuette Dharmek Stupa at Sarnath

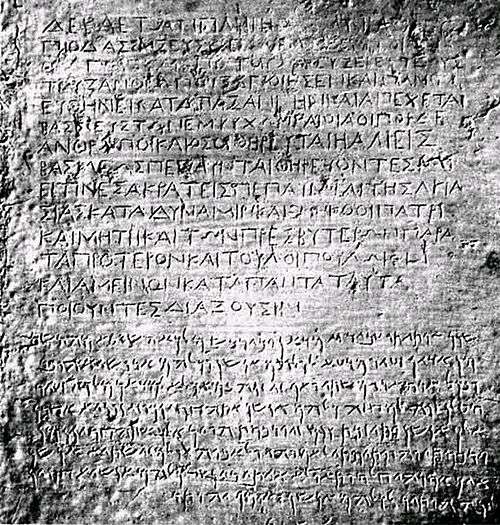

Dharmek Stupa at Sarnath Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (Greek and Aramaic) by king Ashoka, from Kandahar. Kabul Museum.

Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (Greek and Aramaic) by king Ashoka, from Kandahar. Kabul Museum.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art of the Mauryan Empire. |

- ↑ Mahajan V.D. (1960, reprint 2007). Ancient India, New Delhi: S.Chand, New Delhi, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, p.348

- ↑ Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (1999). Introduction to Indian Art, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, ISBN 81-215-0389-2, p.26

- ↑ Mahajan V.D. (1960, reprint 2007). Ancient India, New Delhi: S.Chand, New Delhi, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, p.281

- ↑ Mahajan V.D. (1960, reprint 2007). Ancient India, New Delhi: S.Chand, New Delhi, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, p.349

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thapar, Romila (2001). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564445-X, pp.267-70

- ↑ Report on the excavations at Pātaliputra (Patna); the Palibothra of the Greeks by Waddell, L. A. (Laurence Austine)

- ↑ Report of a tour in Bihar and Bengal, p.3

- 1 2 Thapar, Romila (2001). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564445-X, pp.239-49

- ↑ Kosambi, D.D. (1988). The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, ISBN 0-7069-4200-0, p.164

- ↑ Thapar, Romila (2001). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564445-X, p.289

References

- Thapar, Romila (1973). Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560381-8. OCLC 29809355.

- 'The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical outline' by D.D Kosambi, 1964 reprinted in 1997, Vikas Publications, New Delhi, ISBN 0-7069-8613-X

- 'The Wonder that was India' by A.L Basham, Picador India, ISBN 0-330-43909-X