Matenadaran

The Matenadaran building at night | |

| Established | March 3, 1959 |

|---|---|

| Location |

53 Mashtots Avenue, Yerevan, Armenia |

| Coordinates | 40°11′31″N 44°31′16″E / 40.19207°N 44.52113°E |

| Type | Art museum, archive |

| Director | Hrachya Tamrazyan |

| Curator | Gevork Ter-Vartanian |

| Website |

www |

The Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts (Armenian: Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի անվան հին ձեռագրերի ինստիտուտ (Mesrop Mashtots'i anvan hin dzeragreri institut)), commonly referred to as the Matenadaran (Armenian: ![]() Մատենադարան), is a repository of ancient manuscripts, research institute and museum in Yerevan, Armenia. It holds one of the world's richest depositories of medieval manuscripts and books which span a broad range of subjects, including history, philosophy, medicine, literature, art history and cosmography in Armenian and many other languages.

Մատենադարան), is a repository of ancient manuscripts, research institute and museum in Yerevan, Armenia. It holds one of the world's richest depositories of medieval manuscripts and books which span a broad range of subjects, including history, philosophy, medicine, literature, art history and cosmography in Armenian and many other languages.

History

The earliest mention of the term matenadaran, which means "repository of manuscripts" in Armenian, was recorded in the writings of the fifth century A.D. historian Ghazar Parpetsi, who noted the existence of such a repository at Etchmiadzin Cathedral, where Greek and Armenian language texts were kept.[1] After that, however, the sources remain largely silent on its status.

Thousands of manuscripts in Armenia were destroyed over the course of the tenth to fifteenth centuries during the Turkic-Mongol invasions. According to the medieval Armenian historian Stepanos Orbelian, the Seljuk Turks were responsible for the burning of over 10,000 Armenian manuscripts in Baghaberd in 1170.[1] In 1441, the matenadaran in Sis, the capital of the former Cilician Kingdom of Armenia, was moved to Etchmiadzin and other nearby monasteries.[1] As a result of Armenia being a constant battleground between two major powers, the Matenadaran in Etchmiadzin was pillaged several times, the last of which took place in 1804.[1]

Eastern Armenia's incorporation into the Russian Empire in the first third of the nineteenth century provided a more stable climate for the preservation of the remaining manuscripts. Thus, "a new era started for the Etchmiadzin Matenadaran. The Armenian cultural workers procured new manuscripts and put them in order with more confidence."[2] Whereas in 1828 the curators of the Matenadaran catalogued a collection of only 1,809 manuscripts, in 1914 the collection had increased to 4,660 manuscripts.[1] At the outbreak of World War I, all the manuscripts were sent to Moscow for safekeeping and were kept there for the duration of the war.

Founding

On December 17, 1920, the collection of books and manuscripts held at the headquarters of the Armenian Apostolic Church at Etchmiatzin was confiscated by the Bolsheviks. In a decree issued by Alexander Miasnikyan on March 6, 1922, the manuscripts that had been sent to Moscow were to be returned to Armenia. Combined with other collections, they were declared a property of the state on December 17, 1929. In 1939, the collection was moved to Yerevan and stored at the Alexander Miasnikyan State Library. Finally, on March 3, 1959, the Council of Ministers of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic voted in support of the establishment of a repository to maintain and house the manuscripts in a new building, which was named after Saint Mesrop Mashtots, the creator of the Armenian alphabet, in 1962. In 1954, Armenian academician Levon Khachikyan was appointed as the Matenadaran's director.

The Matenadaran was designed by architect Mark Grigoryan. Located slightly north of the city's center at the foot of a small hill, construction began in 1945 and ended in 1957. The exterior was constructed of basalt but parts of the interior were made of other materials such as marble.[1] In the 1960s, the statues of historical Armenian scholars, Toros Roslin, Grigor Tatevatsi, Anania Shirakatsi, Movses Khorenatsi, Mkhitar Gosh and Frik, were erected on the left and right wings of the building's exterior. The statues of Mesrop Mashots and his pupil are located below the terrace where the main building stands.

On May 14, 2009, upon the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Matenadaran, Armenian state and religious officials conducted the groundbreaking ceremony of the construction of a research institute being built adjacent to the Matenadaran.[4] The construction was finished in 2011 by architect Arthur Meschian, who had started working on the design of the new building at the end of the 1980s.

Objectives

The Matenadaran's main objectives are first and foremost the 1) preservation, restoration, and reproduction of the manuscripts; 2) their procurement; 3) the organization and cataloging of Armenian manuscripts; and 4) the distribution and publication of particularly historically significant Armenian manuscripts in languages asides from Armenian.[1] In 1941, it began publishing its official periodical, Banber Matenadarani (The Matenadaran Herald) which are accompanied with Russian and French abstracts.

Matenadaran collection

The Matenadaran is in possession of a collection of nearly 17,000 manuscripts and 30,000 other documents which cover a wide array of subjects such as historiography, geography, philosophy, grammar, art history, medicine and science.[5] In the first decades of Soviet rule, its collection was largely drawn from manuscripts stored in ecclesiastical structures in the historic regions of Vaspurakan (eastern Turkey, Van region) and Taron (Northeastern Turkey), in schools, monasteries and churches in Armenia and the rest of the Soviet Union (such as those located in New Nakhichevan and the Nersisyan Seminary in Tbilisi), the Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages in Moscow, from the Armenian Apostolic Church's Primacy in Tabriz, the village of Darashamb in Iran, as well as the personal collections given by private donors.[1] In addition to the Matenadaran's Armenian manuscripts, there is a vast collection of historical documents numbering over 2,000 in languages such as Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Japanese and Russian.[6] The Mashtots Matenadaran Ancient Manuscripts Collection was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme Register in 1997 in recognition of its world significance.[7]

Armenian

The Armenian collection at the Matenadaran is abundantly rich in manuscripts dealing in all fields of the humanities, but particularly historiography and philosophy. The writings of classical and medieval historians Movses Khorenatsi, Yeghishe and Aristakes Lastivertsi are preserved here, as are the legal, philosophical and theological writings of other notable Armenian figures. The preserved writings of Grigor Narekatsi and Nerses Shnorhali at the Matenadaran form the cornerstone of medieval Armenian literature.[8]

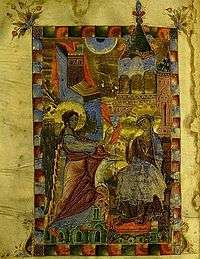

The Armenian collection is also composed of 2,500 Armenian illuminated manuscripts, which include such prominent examples as the Echmiadzin Gospel (989) and the Mugni Gospels (1060). Another prominent manuscript in the collection is the Homilies of Mush, written in the years 1200-1202 A.D. in the Avak Monastery in Yerzenka (modern-day Erzincan, Turkey), which measures 55.3 cm by 70.5 cm (21.8 inches by 27.8 inches), weighs 27.5 kg (60.6 lbs.), and contains 603 calf skin parchment pages.[9] The book was found by two Armenian women in a deserted Armenian monastery in the Ottoman Empire during World War I and the Armenian Genocide period. Since it was found to be too heavy to be carried, it was split into two: one half was wrapped in a cloth and buried, while the second half was taken to Georgia. A couple of years later, a Polish officer found the first half and sold it to an officer in Baku. It was eventually brought to Armenia and the two halves were finally reunited.[10]

Manuscript detail

Manuscript detail Definitions of Philosophy, 5th-6th century

Definitions of Philosophy, 5th-6th century Manuscript illustration detail

Manuscript illustration detail

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (Armenian) Chookaszian, Babken L. and Levon Zoryan. «Մատենադարան» (Matenadaran). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1981, vol. 7, pp. 284-286.

- ↑ Anon. "The History of Matenadaran." Virtual Matenadaran. Accessed April 27, 2009.

- ↑ https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.246067358867.178461.15800878867&type=3

- ↑ Hakobyan, Sona. "Groundbreaking ceremony for a new building of Matenadaran." Radiolur. May 14, 2009. Accessed May 15, 2009.

- ↑ Ritter, Lawrence. "The Matenadaran, from copyist monks to the digital age." UNESCO. № 5, May 24, 2007. Accessed May 3, 2009.

- ↑ Anon. "Scientific Research Institute of Old Manuscripts Matenadaran after St. Mesrop Mashtotz." International Exhibition of Calligraphy. Accessed May 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Mashtots Matenadaran ancient manuscripts collection". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Anon. "The Heritage: Literature." Virtual Matenadaran. Accessed May 15, 2009.

- ↑ "UNESCO Memory of the World Register Nomination Form - The Mashtots Matenadaran Ancient Manuscripts Collection" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- ↑ Chahin, Mack (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia. London: Routledge Curzon. p. 226. ISBN 0-7007-1452-9.

Further reading

- (Armenian) Abgaryan, Gevork V. Մատենադարան (Matenadaran). Yerevan: Armenian State Publishing House, 1962.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matenadaran. |

- Official site

- Dadrian, Eva. "By the book." Al-Ahram Weekly. March 9–15, 2006, Issue No. 785.

- Reviews about Matenadaran