Louis Marx and Company

| |

| Private | |

| Industry | Toys and hobbies |

| Fate | Liquidation |

| Successor | Quaker Oats, Dunbee-Combex-Marx |

| Founded | 1919 |

| Defunct | 1980 |

| Headquarters | New York, New York |

Key people | Louis Marx, Founder, David Marx, Co-founder |

| Products | Lithographed tinplate, plastics, wood products |

Louis Marx and Company was an American toy manufacturer in business from 1919 to 1978. Its products were often imprinted with the slogan, "One of the many Marx toys, have you all of them?" Arguably, Marx was the most well-known toy company through the 1950s.

Logo and offerings

The Marx logo was the letters "MAR" in a circle with a large X through it, resembling a railroad crossing sign (Richardson 1999, p. 66). As the X sometimes goes unseen, Marx toys were, and are still today, often misidentified as "Mar" toys. Reputedly, because of this name confusion, the Italian diecast toy company Martoys, after two years of production, changed its name to Bburago in 1976. Although the Marx name is now largely forgotten except by toy collectors, several of the products that the company developed remain strong icons in popular culture, including Rock'em Sock'em Robots, introduced in 1964, and its best-selling sporty Big Wheel tricycle, one of the most popular toys of the 1970s. In fact, the Big Wheel, which was introduced in 1969, is enshrined in the National Toy Hall of Fame.

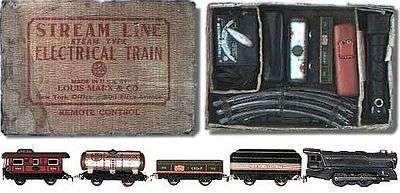

Marx's toys included tinplate buildings, tin toys, toy soldiers, playsets, toy dinosaurs, mechanical toys, toy guns, action figures, dolls, dollhouses, toy cars and trucks, and HO scale and O scale trains. Marx also made several models of typewriters for children. Marx's less expensive toys were extremely common in dime stores, and its larger, costlier toys were staples for catalog retailers such as Sears and Montgomery Ward, especially around Christmas.

History

Founded in 1919 in New York City by Louis Marx and his brother David, the company's basic aim was to "give the customer more toy for less money," and stressed that "quality is not negotiable" - two values that made the company highly successful. Initially, after working for Ferdinand Strauss, Marx, born in 1894, was a distributor with no products or manufacturing capacity (King 1986, p. 188; Richardson 1999, p. 42). Marx raised money as a middle man, studying available products, finding ways to make them cheaper, and then closing sales. Enough funding was raised to purchase tooling from previous employer Strauss for two obsolete tin toys - the Alabama Coon Jigger and Zippo the Climbing Monkey (Time Magazine 1955; King 1986, p. 188). With subtle changes, Marx was able to turn these toys into hits, selling more than eight million of each within two years. Another success was the "Mouse Orchestra" with tinplate mice on piano, fiddle, snare, and one conducting (King 1986, pp. 188-189).

Marx listed six qualities he believed were needed for a successful toy: familiarity, surprise, skill, play value, comprehensibility and sturdiness (Richardson 1999, p. 42). By 1922, both Louis and David Marx were millionaires. Initially, Marx produced few original toys by predicting the hits and manufacturing them less expensively than the competition. The yo-yo is an example: although Marx is sometimes wrongly credited with inventing the toy, the company was quick to market its own version. During the 1920s, about 100 million Marx yo-yos were sold (Time Magazine 1955).

Unlike most companies, Marx's revenues grew during the Great Depression, with the establishment of production facilities in economically hard-hit industrial areas of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and England (Richardson 1999, p. 63). By 1937, the company had more than $3.2 million in assets ($42.6 million in 2005 dollars), with debt of just over $500,000. Marx was the largest toy manufacturer in the world by the 1950s. In 1955, a Time Magazine article proclaimed Louis Marx "the Toy King," and that year, the company had about $50 million in sales (Time Magazine 1955). Marx was the initial inductee in the Toy Industry Hall of Fame, and his plaque proclaimed him "The Henry Ford of the toy industry."

At its peak, Louis Marx and Company operated three manufacturing plants in the United States: Erie, Pennsylvania, Girard, Pennsylvania, and Glen Dale, West Virginia. The Erie plant was the oldest and largest, while the Girard plant, acquired in 1934 with the purchase of Girard Model Works, produced toy trains, and the Glen Dale plant produced toy vehicles (Marx Trains 2007). Additionally, Marx operated numerous plants overseas, and in 1955 five percent of the toys Marx sold in the U.S.A. were made in Japan (Time Magazine 1955).

Playsets

Among the most enduring Marx creations were a long series of boxed "playsets" throughout the 1950s and 1960s based on television shows and historical events. These include "Roy Rogers Rodeo Ranch" and Western Town, "Walt Disney's Davy Crockett at the Alamo", "Gunsmoke", "Wagon Train", "Battle of the Blue and Grey", "The Revolutionary War" (including "Johnny Tremain"), "Tales of Wells Fargo", "The Untouchables", "Robin Hood", "The Battle of the Little Big Horn", "Arctic Explorer", "Ben Hur", "Fort Apache", "Battleground", "Tom Corbett Training Academy", and many others.

Playsets included highly detailed plastic figures and accessories, many with some of the toy world's finest tin lithography. A Marx playset box was invariably bursting with contents, yet very few were ever priced above the average of $4–$7. Greatly expanded sets, such as "Giant Ben Hur" sold for $10 to $12 in the early 1960s. This pricing formula adhered to the Marx policy of "more for less" and made the entire series attainable to most customers for many years. Original sets are highly prized by baby boomer collectors to this day. Collector's books titled "Boy Toys" and "The Big Toy Box at Sears" feature the original advertisements for many of these sets and are well worth having as a visual reference.

Marx produced dollhouses from the 1920s into the 1970s. In the late 1940s Marx began to produce metal lithographed dollhouses with plastic furniture (at the same time it began producing service stations). These dollhouse were variations of the Colonial style. An instant sensation was the "Disney" house, featured in the 1949 Sears catalogue. The popularity of Marx dollhouses gained momentum, and up to 150,000 Marx dollhouses were produced in the 1950s. Two house sizes were available, with two different size furniture to match; the most popular in the 1/2" to 1' scale, and the larger 3/4" to 1' scale. An L-shaped ranch hit the market in 1953, followed by a split-level of 1958. Curiously, in the early 1960s a dollhouse with a bomb shelter was sold briefly.

As the space race heated up, Marx playsets reflected the obsession with all things extraterrestrial such as "Rex Mars", "Moon Base", "Cape Canaveral", and "IGY International Geophysical Year", among other space themed sets. In a similar theme, Marx also capitalized on the robot craze, producing the Big Loo, "Your friend from the Moon", and the popular Rock'em Sock'em Robots action game.

In 1963, Marx began making a series of beatnik style plastic figurines called the Nutty Mads, which included some almost psychedelic creations, such as Donald the Demon — a half-duck, half-madman driving a miniature car. These were similar to the counterculture characters of other companies introduced about a year before, such as Revell's Rat Fink by "Big Daddy" Ed Roth, or Hawk Models' "Weird-Oh's", designed by Bill Campbell (Atomic Home Videos LLC, 2010).

Vehicles

Pre-war

Cast iron was unwieldy, heavy, and not well-suited to proper detail or model proportions and gradually it was replaced by pressed tin (Richardson 1999, p. 67). Marx offered a variety of tin vehicles, from carts to dirigibles — the company would lithograph toy patterns on large sheets of tinplated steel. These would then be stamped, die-cut, folded, and assembled (Vintage Marx 2015). Marx was long known for its car and truck toys, and the company would take small steps to renew the popularity of an old product. In the 1920s, an old truck toy that was falling behind in sales was loaded with plastic ice cubes and the company had a new hit (Time Magazine 1955). The Honeymoon Express, a wind-up train on track with a plane circling above, later became the Mickey Mouse Express and then the Subway Express. Popeye pushing a barrel of spinach eventually became the 1940 Tidy Tim Street Cleaner and Charlie McCarthy in his "Benzine Buggy" (Vintage Marx 2015; Richarson 1999, p. 66).

Some of the most popular vehicles were Crazy Cars like the Funny Flivver of 1926 - another was the eloping "Joy Riders" (Richardson 1998, p. 43). One earlier and much sought after tin toy was an open Amos 'n Andy Ford Model T four door, as well as another Model T with driver apparently on a European jaunt and hauling a trunk at the rear with the names of various European cities on it. This model was produced in a variety of liveries (Richardson 1999, pp. 43, 63). Lithographed tin tanks, airplanes, police motorcycles, tractors, trains, luxury liners, and rocket ships were all produced in bright colors. One toy, the Tricky Taxi seems to have had origins in a Heinrich Muller toy from Nuremberg in Germany (Richardson 1999, p. 63). The 1935 G-Man pursuit car was possibly the largest vehicle Marx ever made at 14 1/2 inches long (Richardson 1999, p. 66). Even doll houses, gasoline stations, parking lots and street scenes were made in tin (Richardson 1999, p. 66). That Marx was doing well even in the depression is shown by the date of introduction of their well-known motorcycle cop toy - 1933 (Richardson 1999, p. 44).

A number of tinplate trucks, buses and vans were made in the 1930s, particularly in the latter part of the decade. Trucks were made, particularly Studebakers, in a variety of colors and formats, and often advertised in Sears catalogs (Tustin 2014). These included several different series like the truck hauling five tinplate "stake bed" trailers, a 'dumping' garbage truck, many variations on larger truck "car carriers" hauling different vehicles, and a set of completely chromed trucks (Tustin 2014). Metal gas and fire station sets could also be purchased on which to play with the vehicles more fully.

Plastics

After World War II Marx introduced more vehicles, taking advantage of molding techniques with various plastics. Pressed tin and steel remained in the form of Buicks, Nashes, or other semi-futuristic sedans, race cars, and trucks that didn't replicate any actual vehicles. One interesting car was a tin Buick-like wood-bodied station wagon. These were often of various larger sizes, ranging from 10 to 20 inches long. Some vehicles were difficult to identify as Marx; one had to look for the small "X-in-O" logo, usually on the lower rear of the vehicle. Often there were no markings on the base.

More and more, however, plastic models appeared in a variety of sizes, three series of which are significant. The first series, in 1950, included cheap 4-inch replicas of early 1950s cars, both foreign and domestic, like Talbot, Volkswagen, Jaguar, Studebaker, Ford, Chevrolet, GMC Van and others. They were supplied as accessories for Marx' large tinplate gas station toy. These were molded of polystyrene and came with die-cast metal wheel-and-axel combinations. The second series was identical, except for updating the cars to 1954 models. The third series, released in 1959, included updated models of 1959 cars, only these were molded in polyethylene and had polyethylene wheels/axels, and were supplied with an updated 1959 gas station. All the Marx 1959 gas station cars were pantographed off current AMT and Jo-Han flywheel models.

In the early 1950s, one Marx product line showed a greater sophistication in toy offerings. The "Fix All" series was introduced, whose main attraction was larger plastic vehicles (about 14 inches long) that could be taken apart and put back together with included tools and equipment. A 1953 Pontiac convertible (erroneously identified as a sedan), and a 1953 Mercury Monterey station wagon which featured an articulated drive-line. Everything from the pistons to the crankshaft to the rear axel gears were visible through clear plastic, and wood-trim decals for the sides finished off this marvelous model. A very large 1953 Chrysler convertible, a 1953 Jaguar XK120 roadster, a WWII-era Willys Jeep, a Dodge-ish utility truck, a tow truck, a tractor, a larger scale motorcycle, a helicopter, and a couple of airplanes were all part of the Fix All series. The cars' boxes boasted features like "Over 50 parts" and "For a real mechanic!" As an example, the tow truck came with cast metal open and box wrenches, an adjustable end wrench, a two-piece jack, gas can, hammer, screwdriver, and fire extinguisher. The Jeep came with a star wrench, a screw jack and working lights.

The Marx Hudson toy

In 1948 the Hudson Motor Car Company made a detailed in-house promotional model of its Commodore for the use of its dealers. The model was exceptional and was not available as a retail toy. Some sources say this model was made by Marx (Automotive News 1948), but others say it was Hudson's own production (Daniel 2013; Model Cars 1979, pp. 34–35). Later, Marx created injection molds from this precision model and Marx continued to made the Hudson, but now as a rather clumsy toy, which was available as a police car in bright green or a fire chief car in bright red. The clear windows of the original were replaced with a single, stamped metal unit with lithographed cartoonish images of policemen or firemen. The police version even had a shotgun protruding through the windshield. Install batteries, and a roof light lit up and the gun made a rat-a-tat sound. Not one of Marx's more successful toys, the Hudson was a large and unwieldy toy for pre-teens. After new Hudsons and other American cars appeared, the model became obsolete, resulting in an oversupply on retail toy shelves. Even by the mid-1960s they were still easy to find in toy stores across America. One could usually buy one for about a dollar - a nice discount from the original $4.95 list price.

A well-preserved Marx police or fire chief Hudson will still bring from $50 to $100 in today's market, depending on condition. An authentic Hudson promotional brings around $2,000. Over the years, professional Hudson collectors have altered the Marx version to resemble the original promotional - these usually bring from $600 to $800.

Other autos

Marx also made Studebaker and Packard vehicles especially through the 1930s and 1940s. They often appeared with the Studebaker badge logo in a very promotional way, though evidence of Marx as a promotional provider is uncertain. One of Marx's later Studebakers was an Avanti with a dented fender that could be replaced with a 'repaired' one, which was odd, as the real Avanti had a fiberglass body - and would not dent. A 1948 Packard Fire Chief's car was one that looked, in theme, much like the step-down Hudson.

Into the 1960s and 1970s, Marx still made some cars, though increasingly these were made in Japan and Hong Kong. Especially impressive were two-foot long "Big Bruiser" tow trucks with Ford C-Series cabs and "Big Job" dump trucks, a T-bucket hot rod of the same large size and some foreign cars like a Jaguar SS100, which was later reissued. Marx made some 1/25 scale slot cars, like a Jaguar XKE remote control convertible. Into the 1970s, Marx jumped on several bandwagons, for example, plastic pull string funny cars of typical 1:25 scale model size, but this was not quick enough to save the company.

Marx sometimes joined with European toy makers, putting their name on traditional European toys. For example, about 1968, Solido and Marx made a deal to sell these French metal die cast models in the U.S. with the Marx name added to the box. The boxes were, for the most part, regular red Solido boxes with the Marx "x-in-o" logo and "by Marx" directly below the Solido script. Nowhere on the cars did the Marx name appear.

The small scale market

During the 1960s Marx offered its Elegant Models, a collection of Matchbox-like 1930s to 1950s style race cars in red and yellow boxes. Also offered were airplanes, trucks, and, in the same series, metal animals boxed in a similar style. Some of the vehicles from this era were marketed under the Linemar or Collectoy names.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Marx tried to compete not only with Matchbox, but with Mattel Hot Wheels, making small cars with thin axle, low-friction wheels. These were marketed, not too successfully, under a few different names. One of the most common was "Mini Marx Blazers" with "Super Speed Wheels". The cars were made in a slightly smaller scale than Hot Wheels, often 1:66 to about 1:70 (Toy Collector 2010). Proportions of these cars were simple, but accurate, though details were somewhat lacking (Ragan 2000, 54). Some cars, however, included such niceties as a driver behind the wheel. While some of the earlier toys had a simpler Tootsietoy style single casting, newer cars were colored in bright chrome paints with decals and fast axle wheels. Tires were plain black with thin whitewalls.

Linemar toys

Linemar toys was the trade name under which Marx toys were manufactured in Japan, then sold in the United States and other countries. The reason to make Linemar toys in Japan was to keep costs down. Under the Linemar name, Marx produced The Flintstones and other licensed toy vehicles (Linemar Tin Toys 2015). The Linemar line also included airplanes that were produced in the colors of KLM, Pan Am and other airlines.

The decline

By the 1970s automotive toy and model producers began losing their 1950s glow, largely due to the government's strict, inflexible safety changes mandated on post-1972 automobiles, and by the late 70's all but one or two were gone. By 1973, cars from Detroit were boring, lack-luster, household appliances that held no appeal for kids born in the 70s. Indeed, computer games, transformers and a revived interest in pre-WWII comic characters were waiting to pounce on the soon-to-be-abandoned huge toy car market that was rapidly dying.

In 1955, with sales of $50 million, Marx spent a mere $312.00 on advertising for the entire year (Time Magazine, [month], 1955). By contrast, Mattel Toys in the same year had sales of $6 million but spent $500,000 for advertising, sponsoring shows like The Mickey Mouse Club (Clark 2007, p. 220). Eventually, the high cost of labor in the United States, always a factor in the distinctive quality of American toys, made it very difficult to compete with toys produced in Asia, and the few efforts still being produced in the US by the 1980s were largely regarded as throw-away junk.

Quaker Oats-Marx era

In 1972, Marx sold his company to the Quaker Oats Company for $54 million ($246 million in 2005 dollars) and retired at the age 76 (Smith 2000, pp. 9–10). Quaker also owned the Fisher-Price brand, but struggled with Marx. Quaker had hoped Marx and Fisher-Price would have synergy, but the companies' sales patterns were too different. Marx was also faulted for largely ignoring the trend towards electronic toys in the early 1970s. In late 1975, Quaker closed the plants in Erie and Girard, and in early 1976, Quaker sold its struggling Marx division to the British conglomerate Dunbee-Combex-Marx, who had bought the former Marx UK subsidiary in 1967.

Dunbee-Combex-Marx era

A downturn in the British economy in conjunction with high interest rates caused Dunbee-Combex-Marx to struggle, and these unfavorable market conditions caused a number of British toy manufacturers, including Dunbee-Combex-Marx, to collapse. By 1979, most U.S. operations were ceased, and by 1980, the last Marx plant closed in West Virginia (Vitello 2006). The Marx brand disappeared and Dunbee-Combex-Marx filed for bankruptcy. The Marx assets were liquidated in the early 1980s, with some trademarks and molding tools going to a few other toy manufacturers of the time, including the Mego Corporation.

Toy legacy

Some popular Marx tooling is still used today to produce toys and trains. A company called Marx Trains, Inc. produced lithographed tin trains, both of original design and based on former Louis Marx patterns. Plastic O scale train cars and scenery using former Marx molds, are now marketed under the "K-Line by Lionel" brand name. Model Power produces HO scale trains from old Marx molds. The Big Wheel rolls on, as a property of Alpha International, Inc. (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), which has been acquired by J. Lloyd International, Inc. also of Cedar Rapids. Mattel reintroduced Rock'em Sock'em Robots around 2000 (albeit at a smaller size than the original). Marx's toy soldiers and other plastic figures are in production today in Mexico, and in the US for the North American market and are mostly targeted at collectors, although they sometimes appear on the general consumer market.

The Marx company name has changed hands numerous times. However, despite the similar name, none of the Marx-branded companies of today can claim a direct lineage to the original Louis Marx and Company.

References

- Automotive News. 1948. Assembly Lines of a New Type Gain Favor. September 27.

- Clark, Eric. 2007. The Real Toy Story, Transworld.

- Daniel, Paul. Promo Model: 1948 Hudson Hornet. Savage on Wheels: Honest Car Reviews - Big and Small ! Online webpage article.

- King, Constance Eileen. 1986. Encyclopedia of Toys. Secaucus, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, A Division of Book Sales, Inc.

- Linemar Tin Toys webpage. 2015. Fabintoys website.

- MarX Trains and Toys Info: The Toy King Louis Marx. 2007. eBay On-line review.

- Model Cars. 1979. By the Editors of Consumer Guide. New York: Beekman House, A Division of Crown Publishers, 72 pages. ISBN 0-517-294605.

- Planet Diecast. 2010. Marx Miniature Cars Miss the Mark. Online webpage.

- Ragan, Mac. 2000. Diecast Cars of the 1960s. Osceola, Wisconsin: MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0719-9.

- Richardson, Mike and Sue. 1998. Wheels: Christie's Presents the Magical World of Automotive Toys. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2320-2

- Smith, Michelle L. 2000. Marx Toys Sampler: A History and Price Guide. Krause Publications.

- Time Magazine. 1955. The Little King. Original magazine article online. Dec. 12.

- Tustin, Jimmy. 2014. Remember When Restorations website. Page dedicated to Marx vehicles.

- Vintage Marx Toys. 2015. Article in Collector's Weekly website.

- Vitello. 2006. Wheeling: Toy Museum Rekindles Visitor's Memories. Louisville Courier-Journal on-line. January 21.

- Kern, Russell S. 2010. Toy Kings: The Story of Louis Marx & Company. Colorado Springs, Colorado: Atomic Home Videos LLC, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Marx and Company. |

- www.marxtoymuseum.com — Marx Toy Museum (Moundsville, West Virginia)

- www.fabtintoys.com — Marx and other retired toy manufacturers