Máel Ruain

| Máel Ruain | |

|---|---|

|

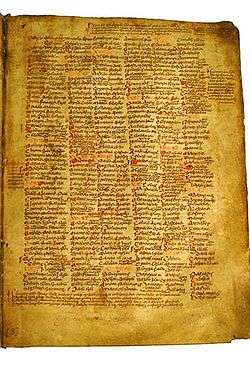

Part of the copy of the Martyrology of Tallaght separated from the Book of Leinster and now at University College, Dublin | |

| abbot-bishop of Tallaght | |

| Died | 792 |

| Feast | July 7 |

| Patronage | Tallaght (Co. Dublin) |

Saint Máel Ruain[1] (died 792) was founder and abbot-bishop of the monastery of Tallaght (Co. Dublin, Ireland). He is often considered to be a leading figure of the monastic 'movement' that has become known to scholarship as the Céli Dé. He is not to be confused with the later namesake Máel Ruain, bishop of Lusca (Co. Dublin).

The foundation of Tallaght

Little is known of his life. Máel Ruain is not his personal name bestowed at birth or baptism, but his monastic name, composed of Old Irish máel ("one who is tonsured") and Ruain ("of Rúadán"), which may mean that he was a monk of St. Rúadán's monastery in Lothra (north Co. Tipperary).[2] Though his background and early career remain obscure, he is commonly credited with the foundation of the monastery of Tallaght, sometimes called "Máel Ruain's Tallaght",[3] in the latter half of the 8th century. This may be supported by an entry for 10 August in the Martyrology of Tallaght, which notes that Máel Ruain came to Tallaght carrying with him "relics of the holy martyrs and virgins" (cum suis reliquiis sanctorum martirum et uirginum),[4] apparently with an eye to founding his house.[3] There is at any rate no evidence for a religious establishment at Tallaght prior to Máel Ruain's arrival and although Tamlachtae, the Old Irish name for Tallaght, refers to a burial ground, it was not yet the rule for cemeteries to be located adjacent to a church.[3] Precise details of the circumstances are unknown. A line in the Book of Leinster has been read as saying that in 774 the monk obtained the land at Tallaght from the Leinster king Cellach mac Dúnchada (d. 776), who came from the Uí Dúnchada sept of the Uí Dúnlainge branch of the Laigin, but there is no contemporary authority from the annals to support the statement.[2] In the Martyrology of Tallaght and the entries for his death in the Irish annals (see below), he is styled a bishop.

Liturgy and teachings

The best known disciple of Máel Ruain's community was Óengus the Culdee, the author of the Félire Óengusso, a versified martyrology or calendar commemorating the feasts of Irish and non-Irish saints, and possibly also of the earlier prose version, the Martyrology of Tallaght. In his epilogue to the Félire Óengusso, written sometime after Máel Ruain's death, Óengus shows himself much indebted to his "tutor" (aite), whom he remembers elsewhere as "the great sun on Meath's south plain" (grían már desmaig Midi).[5] In the early ninth century, Tallaght also seems to have produced the so-called Old Irish Penitential.[6]

Although liturgical concerns are evident in the two martyrologies, there is no strictly contemporary evidence for Máel Ruain's own monastic principles and practices. Evidence for his teachings and their influence comes chiefly by way of a number of 9th-century writings associated with the Tallaght community known collectively as the 'Tallaght memoir'. One of the principal texts is The Monastery of Tallaght (9th century), which claims to list the precepts and habits of Máel Ruain and some of his associates, apparently as remembered by his follower Máel Díthruib of Terryglass.[3][6] Much of the text survives in a 15th-century manuscript, RIA MS 1227 (olim MS 3 B 23), and in the 17th century, an Early Modern Irish paraphrase was produced now referred to as The Teaching of Máel Ruain.[6] Of less certain origin is the text known as the Rule of Céli Dé, which is preserved in the Leabhar Breac (15th century) and contains various instructions for the regulation and observance of monastic life, notably in liturgical matters. It is ascribed to both Óengus and Máel Ruain, but the text in its present form is a prose rendering from the original verse, possibly written in the 9th century by one of his community.[2] These works of guidance appear to have been modelled on the sayings of the Desert Fathers of Egypt, in particular the Conferences of John Cassian.[3] Typical concerns in them include the importance of daily recitation of the Psalter, of self-restraint and forbearance from indulgences in bodily desires and of separation from worldly concerns.[2] Against the practices of earlier Irish monastic movements, Máel Ruain is cited as forbidding his monks to go on an overseas pilgrimage, preferring instead to foster communal life in the monastery.[2][3]

Máel Ruain's reputation as a teacher whose influence on the monastic world extended beyond the confines of the cloister walls is further suggested by the later tract Lucht Óentad Máele Ruain ("Folk of the Unity of Máel Ruain"), which enumerates the twelve most prominent associates who embraced his teachings.[2] They are said to include Óengus, Máel Díthruib of Terryglass, Fedelmid mac Crimthainn, king of Cashel, Diarmait ua hÁedo Róin of Castledermot (Co. Kildare) and Dímmán of Araid.[2]

Death and veneration

The Annals of Ulster report under the year 792 that Máel Ruain died a peaceful death, calling him a bishop (episcopus) and soldier of Christ (miles Christi).[7] In the Annals of the Four Masters, however, in which he is also styled "bishop", his death is assigned, probably incorrectly, to the year 787. His feast in the Martyrology of Tallaght and Félire Óengusso is on July 7.[8] He was succeeded as abbot of Tallaght by Airerán.

References

- ↑ The name is also spelled Maelruain (modernised: Maolruain), and more rarely, Maelruan, Molruan and Melruain.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Byrnes, "Máel-Ruain." In Medieval Ireland. Encyclopedia (2005). pp. 308-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Doherty, "Leinster, saints of." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004).

- ↑ Martyrology of Tallaght, ed. Best and Lawlor, p. 62.

- ↑ Félire Óengusso, ed. Stokes, pp. 266-7 (Epilogue, lines 61-8); p. 26 (Prologue, lines 225-8). See also p. 161 (July 7, Máel Ruain's feastday).

- 1 2 3 Follett, Céli Dé in Ireland, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Annals of Ulster s.a. 792.

- ↑ Martyrology of Tallaght, ed. Best and Lawlor, p. 94-5; Félire Óengusso, ed. Stokes, p. 161.

Primary sources

- Martyrology of Tallaght, ed. Richard Irvine Best and Hugh Jackson Lawlor, The Martyrology of Tallaght. From the Book of Leinster and MS. 5100–4 in the Royal Library. Brussels, 1931.

- Óengus of Tallaght (1905). Stokes, Whitley, ed. The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee. Henry Bradshaw Society. 29. London.

- The Monastery of Tallaght, ed. E.J. Gwynn and W.J. Purton, "The Monastery of Tallaght." Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 29C (1911–12): 115-80. Edition and translation available online from Thesaurus Linguae Hibernicae; PDF available from the Internet Archive.

- The Teaching of Máel Ruain, ed. E.J. Gwynn, The Teaching of Mael‐ruain. Hermathena 44, 2nd Supplement. Dublin, 1927. pp. 1–63.

- The Rule of the Céli Dé, ed. and tr. E.J. Gwynn, The Rule of Tallaght. Hermathena 44, 2nd Supplement. Dublin, 1927. pp. 64–87.

- Lucht Óentad Máele Ruain ("Folk of the Unity of Máel Ruain", also abridged to Óentu Mail/Máel Ruain) in the Book of Leinster, ed. Pádraig Ó Riain, Corpus Genealogiarum Sanctorum Hiberniae. Dublin, 1985. Section 713.

- Annals of Ulster, ed. and tr. Seán Mac Airt and Gearóid Mac Niocaill, The Annals of Ulster (to AD 1131). Dublin, 1983. Online edition at CELT.

Secondary sources

- Byrnes, Michael. "Máel-Ruain." In Medieval Ireland. Encyclopedia, ed. Seán Duffy. New York and Abingdon, 2005. pp. 308–9.

- Doherty, Charles. "Leinster, saints of (act. c.550–c.800)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 14 Dec 2008.

- Follett, Westley. Céli Dé in Ireland. Monastic Writing and Identity in the Early Middle Ages. Studies in Celtic History. London, 2006.

Further reading

- McNamara, Martin. The Psalms in the Early Irish Church. Sheffield, 2000. pp. 357–9.

External links

- St Maelruin's Anglican Church in Tallaght, Ireland

-

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Maelruan". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Maelruan". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Gwynn's translation of the The Rule of the Céli Dé, modified, Celtichristianity.org.