Macroevolution

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Macroevolution is evolution on a scale at or above the level of species, in contrast with microevolution,[1] which refers to smaller evolutionary changes of allele frequencies within a species or population.[2] Macroevolution and microevolution describe fundamentally identical processes on different time scales.[3][4]

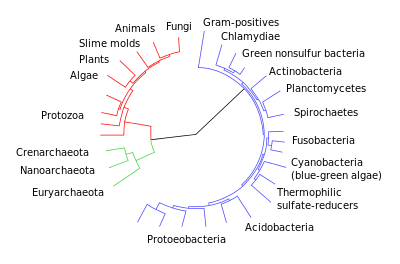

The process of speciation may fall within the purview of either, depending on the forces thought to drive it. Paleontology, evolutionary developmental biology, comparative genomics and genomic phylostratigraphy contribute most of the evidence for macroevolution's patterns and processes.

Origin of the term

Russian entomologist Yuri Filipchenko first coined the terms "macroevolution" and "microevolution" in 1927 in his German language work, "Variabilität und Variation". Since the inception of the two terms, their meanings have been revised several times. The term macroevolution fell into a certain disfavour when it was taken over by writers such as the paleontologist Otto Schindewolf to describe their theories of orthogenesis. This was the vitalist belief that organisms evolve in a definite direction due to an internal "driving force".[5][6]

Macroevolution includes changes occurring on geological time scales, in contrast to microevolution, which occurs on any time scale.[7]

Macroevolution and the modern evolutionary synthesis

Within the modern evolutionary synthesis school of thought, macroevolution is thought of as the compounded effects of microevolution.[8] Thus, the distinction between micro- and macroevolution is not a fundamental one – the only difference between them is of time and scale. As Ernst W. Mayr observes, "transspecific evolution is nothing but an extrapolation and magnification of the events that take place within populations and species...it is misleading to make a distinction between the causes of micro- and macroevolution".[8] However, time is not a necessary distinguishing factor – macroevolution can happen without gradual compounding of small changes; whole-genome duplication can result in speciation occurring over a single generation - this is especially common in plants.[9]

Changes in the genes regulating development have also been proposed as being important in producing speciation through large and relatively sudden changes in animals' morphology.[10][11]

Types of macroevolution

There are many ways to view macroevolution, for example, by observing changes in the genetics, morphology, taxonomy, ecology, and behavior of organisms, though these are interrelated. Sahney et al. stated the connection as "As taxonomic diversity has increased, there have been incentives for tetrapods to move into new modes of life, where initially resources may seem unlimited, there are few competitors and possible refuge from danger. And as ecological diversity increases, taxa diversify from their ancestors at a much greater rate among faunas with more superior, innovative or more flexible adaptations."[12]

Molecular evolution occurs through small changes in the molecular or cellular level. Over a long period of time, this can cause big effects on the genetics of organisms. Taxonomic evolution occurs through small changes between populations and then species. Over a long period of time, this can cause big effects on the taxonomy of organisms, with the growth of whole new clades above the species level. Morphological evolution occurs through small changes in the morphology of an organism. Over a long period of time, this can cause big effects on the morphology of major clades. This can be clearly seen in the Cetacea, where throughout the group's early evolution, hindlimbs were still present. However over millions of years the hindlimbs regressed and became internal.[13]

Abrupt transformations from one biologic system to another, for example the passing of life from water into land or the transition from invertebrates to vertebrates, are rare. Few major biological types have emerged during the evolutionary history of life. When lifeforms take such giant leaps, they meet little to no competition and are able to exploit many available niches, following an adaptive radiation. This can lead to convergent evolution as the empty niches are filled by whichever lifeform encounters them.[14]

Research topics

Subjects studied within macroevolution include:[15]

- Adaptive radiations such as the Cambrian Explosion.

- Changes in biodiversity through time.

- Genome evolution, like horizontal gene transfer, genome fusions in endosymbioses, and adaptive changes in genome size.

- Mass extinctions.

- Estimating diversification rates, including rates of speciation and extinction.

- The debate between punctuated equilibrium and gradualism.

- The role of development in shaping evolution, particularly such topics as heterochrony and phenotypic plasticity.

See also

- Darwin (unit), a unit of evolutionary change, defined as an e-fold (about 2.718) change in a trait over one million years

- List of transitional fossils

- Transitional fossil

- Speciation

Notes

- ↑ Dobzhansky, Theodosius Grigorievich (1937). Genetics and the origin of species. New York: Columbia Univ. Press. p. 12. LCCN 37033383.

- ↑ Reznick DN, Ricklefs RE (February 2009). "Darwin's bridge between microevolution and macroevolution". Nature. 457 (7231): 837–42. doi:10.1038/nature07894. PMID 19212402.

- ↑ (Matzke & Gross 2006)

- ↑ Futuyma, Douglas (1998). Evolutionary Biology. Sinauer Associates. p. 25. ISBN 0-87893-189-9.

- ↑ Bowler, Peter J. (1989). Evolution: The History of an Idea. University of California Press. pp. 268-270. ISBN 0-520-06385-6

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst. (1988). Toward a New Philosophy of Biology: Observations of an Evolutionist. Harvard University Press. p. 499. ISBN 0-674-89666-1

- ↑ Gingerich, P. D. (1987). "Evolution and the fossil record: patterns, rates, and processes". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 65 (5): 1053–1060. doi:10.1139/z87-169.

- 1 2 Kutschera U, Niklas KJ (June 2004). "The modern theory of biological evolution: an expanded synthesis". Die Naturwissenschaften. 91 (6): 255–76. doi:10.1007/s00114-004-0515-y. PMID 15241603.

- ↑ Rieseberg LH, Willis JH (August 2007). "Plant Speciation". Science. 317 (5840): 910–4. doi:10.1126/science.1137729. PMC 2442920

. PMID 17702935.

. PMID 17702935. - ↑ Valentine JW, Jablonski D (2003). "Morphological and developmental macroevolution: a paleontological perspective". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 47 (7–8): 517–22. PMID 14756327.

- ↑ Johnson NA, Porter AH (2001). "Toward a new synthesis: population genetics and evolutionary developmental biology". Genetica. 112–113: 45–58. doi:10.1023/A:1013371201773. PMID 11838782.

- ↑ Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. and Ferry, P.A. (2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land" (PDF). Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204

. PMID 20106856.

. PMID 20106856. - ↑ McGowen, M. R.; Gatesy, J; Wildman, D. E. (2014). "Molecular evolution tracks macroevolutionary transitions in Cetacea". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 29 (6): 336–46. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.04.001. PMID 24794916.

- ↑ Introduction to Ecology (1983) - J.C. Emberlin, chapter 8

- ↑ Grinin, L., Markov, A. V., Korotayev, A. Aromorphoses in Biological and Social Evolution: Some General Rules for Biological and Social Forms of Macroevolution / Social evolution & History, vol.8, num. 2, 2009

References

- Matzke, Nicholas J. and Gross, Paul R. (2006), "Analyzing Critical Analysis: The Fallback Antievolutionist Strategy", in Eugenie Scott and Glenn Branch, Not in Our Classrooms: Why Intelligent Design is Wrong for Our Schools, Boston: Beacon Press, pp. 28–56, ISBN 0-80-703278-6

- AAAS, American Association for the Advancement of Science (16 February 2006). "Statement on the Teaching of Evolution" (pdf). aaas.org. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- IAP, Interacademy Panel (2006-06-21). IAP Statement on the Teaching of Evolution (PDF). interacademies.net. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- Myers, P.Z. (2006-06-18). Ann Coulter: No Evidence for Evolution?. Pharyngula. ScienceBlogs. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- NSTA, National Science Teachers Association (2007). "An NSTA Evolution Q&A". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- Pinholster, Ginger (19 February 2006). "AAAS Denounces Anti-Evolution Laws as Hundreds of K-12 Teachers Convene for 'Front Line' Event". aaas.org. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

External links

- Introduction to macroevolution

- Macroevolution as the common descent of all life

- Macroevolution in the 21st century Macroevolution as an independent discipline.

- Macroevolution FAQ