Lythronax

| Lythronax Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 80 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Tyrannosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Tyrannosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Lythronax Loewen et al., 2013 |

| Type species | |

| †Lythronax argestes Loewen et al., 2013 | |

Lythronax is an extinct genus of tyrannosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived around 80.6 to 79.9 million years ago in what is now southern Utah, USA. The generic name is derived from the Greek words lythron meaning "gore" and anax meaning "king". Lythronax was a large sized, moderately-built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore that could grow up to an estimated 8 m (26.2 ft) in length and weighed 2.5 tonnes (5,500 lb).

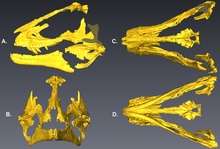

L. argestes is the oldest known tyrannosaurid, based on its stratigraphic position. It is known from a specimen thought to be from a single adult that consists of a mostly complete skull, both pubic bones, a tibia, fibula, and metatarsal II and IV from the left hindlimb, as well as an assortment of other bones. Its skull anatomy indicates that, like Tyrannosaurus, Lythronax had both eyes facing the front, giving it depth perception.

Description

It has been estimated that Lythronax would have been about 7.3 m (24.0 ft) long, with a weight of around 2.5 tonnes (5,500 lb), based on comparisons to close relatives, and had a large skull filled with sharp teeth.[1][2] The rostrum of its skull is comparatively short, since it makes up less than two thirds of the total skull length. The whole skull is very broad, and is only about 2.5 times as long as it is wide. Overall, the skull is morphologically most similar to that of Tyrannosaurus and Tarbosaurus. Its robust maxilla possessed a heterodont dentition, as its first five teeth are a lot larger than the other six. Like other tyrannosaurids, Lythronax has large, distally expanded pubic boot which is approximately 60% the length of the pubic bone. The postcranial morphology is similar to that of other tyrannosaurids.[3]

Discovery

Lythronax is known from the most complete tyrannosaurid specimen discovered from southern Laramidia. The careful excavation took nearly a year.[1] This specimen is housed in the collection of Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. The holotype specimen UMNH VP 20200 was recovered in the UMNH VP 1501 locality of the Wahweap Formation at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM), in Kane County, southern Utah. It was discovered in 2009 and collected from the lower part of the middle member of this formation in terrestrial sediments. The sediments were radioisotopically dated as being 79.6 to 80.75 million years old, meaning that Lythronax is approximately 80 million years old.[3] Based on its stratigraphic position, L. argestes is the oldest tyrannosaurid dinosaur discovered so far.[1][2][3]

Lythronax was named for its likeness to Tyrannosaurus. Loewen et al. wanted to symbolize that the fossil was alike in most features to the much later tyrannosaurid. They decided to keep the 'king' in the name and without using 'rex', named it Lythronax, the "Gore King", accordingly. For the specific name they agreed to use argestes, relating to the area where the fossil was found, southwest Utah.[1][3] The generic name is derived from the Greek λύθρον, lythron, 'gore' and ἄναξ, anax, 'king'. The specific name is the Greek ἀργεστής, "clearing", used by the poet Homer as the epithet of the southwind.[2]

Lythronax is known from a partial skeleton and its diagnostic features include a reduced alveoli count in the maxilla, a concave lateral margin of the dentary, its tall cervical neural spine and a broad caudal portion of the skull. The holotype specimen consists of the right maxilla, both nasal bones, the right frontal, the left jugal, the left quadrate, the right laterosphenoid, the right palatine, the left dentary, the left splenial, the left surangular, the left prearticular, a dorsal rib, a caudal chevron, both pubic bones, the left tibia and fibula, and left metatarsals II and IV. Based on the assemblage, the fossils are considered to have come from one individual, which was an adult.[3]

Classification

Lythronax argestes belongs to the family Tyrannosauridae, a family of large-bodied coelurosaurs, with most genera known from North America and Asia. A detailed phylogenetic analysis, based on 303 cranial and 198 postcranial features, places it and Teratophoneus within Tyrannosaurinae. Lythronax is a sister taxon of a clade consisting of the Maastrichtian taxa Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus and the late Campanian Zhuchengtyrannus.[3] Lythronax probably was not a direct ancestor of Tyrannosaurus. If not, they clearly shared a common ancestor that was even older than Lythronax.[1]

Previously, palaeontologists had thought there were multiple exchanges of tyrannosauroids between Asia and North America, with various forms moving between the continents via what is now Alaska and the Bering Strait into northern Russia. New studies have disrupted that hypothesis. It has been recently suggested that almost all of the Asian tyrannosauroids were part of one evolutionary lineage. It is now thought that there were separate evolutionary radiations in North America of northern and southern tyrannosaurids, with Lythronax being placed as part of the southern group.[3] Research on UMNH VP 16690 supports that theory.[4]

A 2013 study edited by Alan L. Titus and Mark A. Loewen on dinosaurs of southern Utah suggested the separation of Teratophoneus, Bistahieversor and Lythronax (UMNH VP 20200 - the Waheap tyrannosaurid). That means that there are three or more tyrannosaurid taxa present in the Western Interior Basin. Their analysis found that the three southern tyrannosaurid form a clade to the exclusion of other tyrannosaurids from northern Campanian formations.[4]

Below is the cladogram by Loewen et al. in 2013.[3]

| Tyrannosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleobiology

Vision

Lythronax is known from a well preserved skull. It had unique characteristics for its age; a short, narrow snout and a wide skull back, with forward-oriented eyes. These characteristics were originally thought to have evolved late in the Cretaceous, but the discovery of Lythronax pushed the origin of the body form back. This skull anatomy would have given Lythronax overlapping vision, allowing it to perceive depth, which is considered to be a predatory condition.[1] Loewen observed that Tyrannosaurus had a similar anatomy.[5]

Feeding

The shape and position of the skull has been perceived to be linked to how tyrannosaurines would bite, which by extension, probably also links to feeding and killing. This observation suggests that Lythronax had a style of biting rather different from other tyrannosaurines. This has been suggested even though the position of some skulls of tyrannosaurines have been noticed to alter quite considerably. The discovery of Lythronax suggests a very different pattern of evolution for skull shape than has previously been considered.[6]

Lythronax is known from some large teeth. It has been stated that these resembled banana-shaped meat cleavers, although somewhat smaller. Its teeth are serrated, but also quite beefy. It is suggested that they weren’t just for slicing off meat, but also for inflicting damage and crushing bone.[7] The shape of the teeth would have made Lythronax an efficient hunter; it would have been able to carve out huge chunks of flesh and bone and swallow whole.[8]

Paleoecology

Habitat

The Wahweap Formation has been radiometrically dated as being between 81 and 76 million years old.[9] During the time that Lythronax lived, the Western Interior Seaway was at its widest extent, almost completely isolating southern Laramidia off from the rest of North America. It has been suggested that the isolation of Laramidia may have helped tyrannosaurids develop advantageous features, like very powerful jaws. Laramidia may have been the original home of tyrannosaurid theropods. Lythronax was likely the largest predator of its ecosystem.[1] The area where dinosaurs existed included lakes, floodplains, and east-flowing rivers. The Wahweap Formation is part of the Grand Staircase region, an immense sequence of sedimentary rock layers that stretch south from Bryce Canyon National Park through Zion National Park and into the Grand Canyon. The presence of rapid sedimentation and other evidence suggests a wet, seasonal climate.[10]

Paleofauna

Lythronax shared its paleoenvironment with other dinosaurs, such as the hadrosaur Acristavus gagslarsoni and lambeosaur Adelolophus hutchisoni,[11] the ceratopsian Diabloceratops eatoni,[1][12][13] and unnamed ankylosaurs and pachycephalosaurs.[14] Vertebrates present in the Wahweap Formation at the time of Lythronax included freshwater fish, bowfins, abundant rays and sharks, turtles like Compsemys, crocodilians,[15] and lungfish.[16] A fair number of mammals lived in this region, which included several genera of multituberculates, cladotherians, marsupials, and placental insectivores.[17] The mammals are more primitive than those that lived in the area that is now the Kaiparowits Formation. Trace fossils are relatively abundant in the Wahweap Formation, and suggest the presence of crocodylomorphs, as well as ornithischian and theropod dinosaurs.[18] In 2010, a unique trace fossil was discovered that suggests a predator-prey relationship between dinosaurs and primitive mammals. The trace fossil includes at least two fossilized mammalian den complexes, as well as associated digging grooves presumably caused by a maniraptoran dinosaur. The proximity indicates a case of probable active predation of the burrow inhabitants by the animals that made the claw marks.[19] Invertebrate activity in this formation ranged from fossilized insect burrows in petrified logs[20] to various mollusks, large crabs,[21] and a wide diversity of gastropods and ostracods.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Vergano, Dan (Nov 6, 2013). "Newfound "King of Gore" Dinosaur Ruled Before T. rex". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 "'Gore King of the Southwest', Lythronax argestes". Natural History Museum of Utah. Nov 6, 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Loewen, M.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Currie, P. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2013). Evans, David C, ed. "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79420. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420.

- 1 2 Titus, A., Loewen, M. (2013). At the Top of the Grand Staircase: The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Indiana University Press. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-253-00883-1.

- ↑ White, MacRinac (6 November 2013). "New Dinosaur Species, Lythronax Argestes, Discovered In Utah". LiveScience. Stephanie Pappas. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "Lythronax argestes: a new tyrant and the spread of the tyrannosaurs". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "King of gore dinosaur was the 'bad grandpa' of tyrannosaurs". Los Angeles Times. Geoffrey Mohan. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "Toothy Dino Terrorized Utah Before T. rex". Discovery NEWS. Jennifer Viegas. Nov 6, 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ M. A. Getty, M. A. Loewen, E. M. Roberts, A. L. Titus, and S. D. Sampson. 2010. Taphonomy of horned dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah. In M. J. Ryan, B. J. Chinnery-Allgeier, D. A. Eberth (eds.), New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. p. 478–494 ISBN 978-0-253-35358-0

- ↑ Jinnah, Zubair A. (2009). "Sequence Stratigraphic Control from Alluvial Architecture of Upper Cretaceous Fluvial System - Wahweap Formation, Southern Utah, U.S.A." (PDF). Search and Discovery Article # 30088. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ↑ Terry A. Gates; Zubair Jinnah; Carolyn Levitt; Michael A. Getty (2014). "New hadrosaurid specimens from the lower-middle Campanian Wahweap Formation of Utah". In David A. Eberth; David C. Evans. Hadrosaurs: Proceedings of the International Hadrosaur Symposium. Indiana University Press. pp. 156–173. ISBN 978-0-253-01385-9.

- ↑ Gates, T. A.; Horner, J. R.; Hanna, R. R.; Nelson, C. R. (2011). "New unadorned hadrosaurine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (4): 798. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.577854.

- ↑ "Diabloceratops eatoni". Natural History Museum of Utah. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ "New Horned Dinosaurs from the Wahweap Formation" (PDF). Utah Geology. 2007.

- ↑ Thompson, Cameron R. (2004). "A preliminary report on biostratigraphy of Cretaceous freshwater rays, Wahweap Formation and John Henry Member of the Straight Cliffs Formation, southern Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 36 (5): 43.

- ↑ Orsulak, M.; Simpson, E.L.; Wolf, H.I.; Simpson, W.S.; Tindall, S.S.; Bernard, J. Jenesky, T. (2007). "A lungfish burrow in late Cretaceous upper capping sandstone member of the Wahweap Formation Cockscomb ara, Grand Staircase-Escalanta National Monument, Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 39 (5): 43.

- ↑ Eaton, J.G; Cifelli, R.L (2005). "Review of Cretaceous mammalian paleontology; Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 37 (7): 115.

- ↑ Tester, E.; Simpson, E.L.; Wolf, H.I.; Simpson, W.S.; Tindall, S.S.; Bernard, J.; Jenesky T. (2007). "Isolated vertebrate tracks from the Upper Cretaceous capping sandstone member of the Wahweap Formation; Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 39 (5): 42.

- ↑ Simpson, E. L.; Hilbert-Wolf, H. L.; Wizevich, M. C.; Tindall, S. E.; Fasinski, B. R.; Storm, L. P.; Needle, M. D. (2010). "Predatory digging behavior by dinosaurs". Geology. 38 (8): 699. doi:10.1130/G31019.1.

- ↑ De Blieux, D.D. (2007). "Analysis of Jim's hadrosaur site; a dinosaur site in the middle Campanian (Cretaceous) Wahweap Formation of Grand Staircas-Escalante National Monument (GSENM), southern Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 39 (5): 6.

- ↑ Kirkland, J.I.; De Blieux, D.D.; Hayden, M. (2005). "An inventory of paleontological resources in the lower Wahweap Formation (lower Campanian), southern Kaiparowits Plateau, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 37 (7): 114.

- ↑ Williams, J.A.J.; Lohrengel, C.F. (2007). "Preliminary study of freshwater gastropods in the Wahweap Formation, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 39 (5): 43.