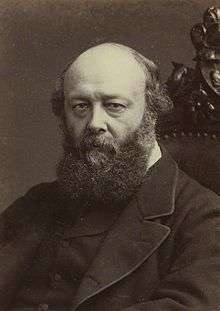

Lord Randolph Churchill

| The Right Honourable Lord Randolph Churchill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

|

In office 3 August 1886 – 22 December 1886 | |

| Prime Minister | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by | William Vernon Harcourt |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Goschen |

| Leader of the House of Commons | |

|

In office 3 August 1886 – 14 January 1887 | |

| Prime Minister | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Succeeded by | William Henry Smith |

| Secretary of State for India | |

|

In office 24 June 1885 – 28 January 1886 | |

| Prime Minister | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Kimberley |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Kimberley |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill 13 February 1849 Belgravia, London, United Kingdom |

| Died |

24 January 1895 (aged 45) London, England, United Kingdom |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) | Jennie Jerome |

| Children |

Winston Churchill John Churchill |

| Alma mater | Merton College, Oxford |

| Profession | Politician |

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a genuine Tory radical, who coined the term Tory Democracy. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of the Conservative Party, broke new ground in modern budgetary presentations, attracting admiration and criticism alike from across the political spectrum. His most acerbic critics resided in his own party among his closest friends; but his disloyalty to Lord Salisbury was the beginning of the end of what should have been a glittering career. His devoted son, Winston, who hardly knew his father in life, wrote a biography of him.[1]

Early life

Born at 3 Wilton Terrace, Belgravia, London. Randolph Spencer was the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, and his wife, Lady Frances Vane. He was at first privately educated, and later attended Tabor's Preparatory School, Cheam, London. In January 1863 he travelled the short distance by private train to Eton College, where he remained until July 1865. He did not stand out either at academic work or sport while at Eton; his contemporaries describe him as a vivacious and rather unruly boy.

Among lifelong friendships made at school were Edward Hamilton and Archibald Primrose. In October 1867 he matriculated and was admitted at Merton College, Oxford. At Oxford, Primrose, now Lord Dalmeny, joined him at the champagne-fuelled parties as members of the Bullingdon Club.[2] Randolph was frequently in trouble with the university authorities for drunkenness, smoking in academic dress, and smashing windows at the Randolph Hotel. His rowdy behavior was infectious, rubbing off on friends and contemporaries; he gained a reputation as an enfant terrible.[3] He had a liking for sport, but was an avid reader, playing hard and working hard.

Churchill experienced none of the early doubts but made many mistakes, as alluded to in Rosebery's biography.[4] He never regretted being an early friend and admirer of the Disraelis. It was however the later cause of dissension that emerged in his relations with a colder more aloof, disciplinarian Salisbury, of whom he fell foul of party challenges. Churchill's youthful exuberance did not prevent him gaining a second-class degree in jurisprudence and modern history in 1870. A year later Churchill and his elder brother, George, were initiated into the rites of Freemasonry, as later his son Winston would be.[5]

Disraeli appointed the Duke to be Viceroy of Ireland, in part compensation for the family's farrago with the Prince of Wales, who belatedly recommended Randolph accompany his father as private secretary. Randolph immediately expressed a desire for politics, so at the general election the following year was elected to Parliament as Conservative member for Woodstock, nest the family seat, defeating George Brodrick, a Fellow, and afterwards Warden, of Merton. His maiden speech, delivered in his first session, prompted compliments from Harcourt and Disraeli, who wrote to the Queen of Churchill's "energy and natural flow."

Influential marriage

Lord Randolph Churchill married a New Yorker Jennie Jerome, daughter of Leonard Jerome, on 15 April 1874. The couple had two sons:

- Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill (1874–1965)

- John Strange "Jack" Spencer-Churchill (1880–1947)

In January 1875, only a month after Winston's birth, Randolph made repeated visits for an undisclosed ailment to the family doctor, Dr Oscar Clayton, a specialist in the treatment of syphilis at his London practice at 5, Harley Street. According to Frank Harris, the editor of Fortnightly Magazine, who published the allegation in his scandalous 1924 autobiography, My Life and Loves, "Randolph had caught syphilis..." Dr Clayton was, however, a "society doctor" with many patients among the British upper class. [6]

Harris' book recounted a story told by Louis Jennings, who had published Randolph's 1880-1888 speeches, to support the syphilis claim. Jennings, however, who was dead when Harris recounted the story, was not a reliable source: his friendship with Churchill had ended acrimoniously after Randolph attacked the Tory party and several of its members in 1893. Jennings' account as reported by Harris has never been corroborated. By 1924, Harris had fallen out with Winston Churchill, for whom he had been a literary agent. Harris had made similar but false or unsubstantiated assertions about Oscar Wilde and Guy de Maupassant.[7]

Recent suggestions presented by London's Churchill Centre and Museum call into question Harris' veracity and offer the alternative theory of a "left side brain tumour", which they claim would be more consistent with Churchill's observed afflictions. The Centre noted that "There is no indication that Lady Randolph or her sons were infected with syphilis. If it is accepted, as reported, that both boys were born prematurely, this was more likely to have been due to a weak opening to the womb than to the disease. If the boys were not born prematurely, that would cast even greater doubt on a diagnosis of syphilis. Neither son was born with the infections that resemble secondary syphilis, nor did they have late hereditary syphilis, commonest between the ages of 7 and 15, manifested by deafness, partial blindness and/or notched teeth."[7]

The "Fourth Party"

It was not until 1878 that he came to public notice as the exponent of independent Conservatism. He made a series of furious attacks on Sir Stafford Northcote, R. A. Cross, and other prominent members of the "old gang". George Sclater-Booth (afterwards 1st Baron Basing), President of the Local Government Board, was a specific target, and the minister's County Government Bill was fiercely denounced as the "crowning dishonour to Tory principles", and the "supreme violation of political honesty". Lord Randolph's attitude, and the vituperative fluency of his invective, made him a parliamentary figure of some importance before the dissolution of the 1874 parliament, though he was not yet taken quite seriously, owing to his high-pitched hysterical laugh.[8]

In the new parliament of 1880 he speedily began to play a more notable role. Along with Sir Henry Drummond-Wolff, Sir John Gorst and occasionally Arthur Balfour, he made himself known as the audacious opponent of the Liberal administration and the unsparing critic of the Conservative front bench. The "fourth party", as it was nicknamed, at first did little damage to the government, but awakened the opposition from its apathy; Churchill roused the Conservatives by leading resistance to Charles Bradlaugh, the member for Northampton, who, though an avowed atheist or agnostic, was prepared to take the parliamentary oath. Sir Stafford Northcote, the Conservative leader in the Lower House, was forced to take a strong line on this difficult question by the energy of the fourth party.

The long controversy over Bradlaugh's seat showed that Lord Randolph Churchill was a parliamentary champion who added to his audacity much tactical skill and shrewdness. He continued to play a conspicuous part throughout the parliament of 1880 to 1885, targeting William Ewart Gladstone as well as the Conservative front bench, some of whose members, particularly Sir Richard Cross and William Henry Smith, he singled out for attack when they opposed the reduced Army estimates. This would be the cause for his resignation because Salisbury failed to support his Chancellor in cabinet. They opposed his unionist politics of 'economising' by Tory tradition making Randolph grow to hate cabinet meetings.[9]

From the beginning of the Egyptian imbroglio Lord Randolph was emphatically opposed to almost every step taken by the government. He declared that the suppression of Urabi Pasha's rebellion was an error, and the restoration of the khedive's authority a crime. He called Gladstone the "Moloch of Midlothian", for whom torrents of blood had been shed in Africa. He was equally severe on the domestic policy of the administration, and was particularly bitter in his criticism of the Kilmainham Treaty and the rapprochement between the Gladstonians and the Parnellites.

Tory Democracy

By 1885 he had formulated the policy of progressive Conservatism which was known as "Tory Democracy". He declared that the Conservatives ought to adopt, rather than oppose, popular reforms, and to challenge the claims of the Liberals to pose as champions of the masses. His views were largely accepted by the official Conservative leaders in the treatment of the Gladstonian Franchise Bill of 1884. Lord Randolph insisted that the principle of the bill should be accepted by the opposition, and that resistance should be focused on the refusal of the government to combine with it a scheme of redistribution. The prominent, and on the whole judicious and successful, part he played in the debates on these questions, still further increased his influence with the rank and file of the Conservatives in the constituencies.

At the same time he was actively spreading the gospel of democratic Toryism in a series of platform campaigns. In 1883 and 1884 he invaded the radical stronghold of Birmingham, and in the latter year took part in a Conservative garden party at Aston Manor, at which his opponents paid him the compliment of raising a serious riot. He gave constant attention to the party organisation, which had fallen into considerable disorder after 1880, and was an active promoter of the Primrose League.

Central Office & National Union

In 1884 progressive Toryism won out. At the conference of the Central Union of Conservative Associations, Lord Randolph was nominated chairman, despite the opposition of the parliamentary leaders. A split was averted by Lord Randolph's voluntary resignation which he had done his best to engineer; but the episode had confirmed his title to a leading place in the Tory ranks.[10] He built up Tory Democracy in the towns reinforcing the urban middle classes part n the party, while simultaneously including a working-class element. His unsuccessful bid for the party leadership was inextricably part of the National Union's attempt to control the party organization.[11] It had originally been founded by Tory peers to organize propaganda to attract working men's votes, registration, choose candidates, conduct elections; associations were linked to provincial unions. Lord Randolph was not the originator but his campaign of 1884 encouraged the leadership to improve on their designs. For the first time since 1832 the Conservatives won in the majority of English boroughs in November 1885.[12]

It was strengthened by the prominent part he played in the events immediately preceding the fall of the Liberal government in 1885; and when Hugh Childers's budget resolutions were defeated by the Conservatives, aided by about half the Parnellites, Lord Randolph Churchill's admirers were justified in proclaiming him to have been the "organiser of victory".

His services were, at any rate, far too important to be refused recognition; and in Lord Salisbury's 'caretaker' cabinet he was made Secretary of State for India on 24 June 1885.[13] As the price of entry he demanded that Sir Stafford Northcote be removed from the Commons, despite being the Conservative leader there. Salisbury was more than willing to concede this and Northcote went to the Lords as the Earl of Iddlesleigh. During his tenure at the India Office during the short-lived minority Conservative administration, Churchill reversed policy over Burma. He sided with commercial interests and directed the Viceroy, Lord Dufferin, to invade Upper Burma in November 1885. With little discussion, Churchill then decided to annexe the final remnant of the once great Burmese kingdom, adding it as a new province of the Indian Raj as a "New Year present" for Queen Victoria on New Year's Day 1886. Soldier and explorer Sir Francis Younghusband considered Churchill the best Secretary of State the India Office ever had.[14]

In the autumn election of 1885 he contested Birmingham Central against John Bright, and though defeated here, was at the same time returned by a very large majority for South Paddington. In the contest which arose over William Ewart Gladstone's Home Rule bill, Lord Randolph again bore a conspicuous part, and in the electioneering campaign his activity was only second to that of some of the Liberal Unionists, Lord Hartington, George Goschen and Joseph Chamberlain. He was now the recognised Conservative champion in the Lower Chamber, and when the second Salisbury administration was formed after the general election of 1886 he became Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons.

Eclipse

His management of the House was largely successful, marked by tact, discretion and temper. But he resigned suddenly on 20 December 1886. Various motives influenced him in taking this surprising step; but the only ostensible cause was put forward in his letter to Lord Salisbury, which was read in the House of Commons on 27 January. In this document he stated that his resignation was the result of his inability, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, to concur in the demands made on the Treasury by the ministers at the head of the naval and military establishments. It was commonly supposed that he expected his resignation to be followed by the unconditional surrender of the cabinet, and his restoration to office on his own terms. The cabinet was reconstructed with Goschen as Chancellor of the Exchequer. For the next few years there was some speculation about a return to front-line politics but Churchill's own career as a Conservative chief was over; even so his ideas survived yet in the Dartford Programme of September 1886.[15]

Although he continued to sit in Parliament, his health was in serious decline throughout the 1890s. He was an ardent supporter of horse-racing, and, in 1889, he won the Epsom Oaks with a mare named the Abbesse de Jouarre. In 1891, he went to South Africa, in search both of health and relaxation. He traveled for some months through Cape Colony,[16] the Transvaal and Rhodesia, making notes on the politics and economics of the countries, shooting lions, and recording his impressions in letters to a London newspaper, which were afterwards republished under the title of Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa. He attacked Gladstone's Second Home Rule Bill with energy, and gave fiery pro-Union speeches in Ireland.

During this time he coined the phrase "Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right", echoing his earlier remark that in opposing Irish Home Rule "the Orange card would be the one to play". But it was soon apparent that his powers were undermined by the illness which took his life at the age of 45. As the session of 1893 wore on, his speeches lost their old effectiveness. His last speech in the House was delivered in the debate on Uganda in June 1894, and was a painful failure. An attempted round-the-world journey failed to cure him. Lord Randolph started in the autumn of 1894, accompanied by his wife, but his health soon became so feeble that he was brought back hurriedly from Cairo. He reached England shortly before Christmas and died in London. The gross value of his personal estate was entered in the Probate Registry at £75,971.[17] This is the financial equivalent of over £6.45 million in 2008 terms, using the retail price index.[18] He is buried near his wife and sons at St Martin's Church, Bladon, near Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Rosebery described his old friend and political opponent's death as one of "his nervous system was always tense and highly strung; ...he seems to have had no knowledge of men, no consideration of their feelings, no give and take." But he continued, "in congenial society, his conversation was wholly delightful. He would then display his mastery of pleasant irony and banter; for with those playthings he was at his best." Lord Randolph's charm undoubtedly appealed to Jennie Jerome, attracting her considerable emotional intelligence.[19]

His widow, Lady Randolph Churchill, married George Cornwallis-West in 1900, when she became known as Mrs. George Cornwallis-West. After that marriage was dissolved, she resumed by deed poll her prior married name, Lady Randolph Churchill. (Lord Randolph was her husband's courtesy title as the younger son of a duke and in English law does not qualify as a noble title in its own right.) Lord Randolph's son, Sir Winston Churchill, died on 24 January 1965, aged 90, exactly 70 years after the death of his father, having lived twice as long.

Family

- Parents

- John Spencer-Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough

- Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane (15 April 1822 – 16 April 1899), the eldest daughter of the 3rd Marquess of Londonderry and Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane-Tempest.

- Siblings

- George Charles Spencer-Churchill, 8th Duke of Marlborough (13 May 1844 – 9 November 1892)

- Lord Frederick John Winston Spencer-Churchill (2 February 1846 – 5 August 1850)

- Lady Cornelia Henrietta Maria Spencer-Churchill (17 September 1847 – Upper Brook Street, Mayfair, London, 22 January 1927), married 25 May 1868 Ivor Bertie Guest, 1st Baron Wimborne, by whom she had issue.

- Lady Rosamund Jane Frances Spencer-Churchill (1851– 3 December 1920), married 12 July 1877 William Fellowes, 2nd Baron de Ramsey, by whom she had issue

- Lady Fanny Octavia Louise Spencer-Churchill (29 January 1853 – 5 August 1904), married 9 June 1873 Edward Marjoribanks, 2nd Baron Tweedmouth, by whom she had issue.

- Lady Anne Emily Spencer-Churchill (Lower Brook Street, Mayfair, London, 14 November 1854 – South Audley Street, Mayfair, London, 20 June 1923), married 11 June 1874 James Innes-Ker, 7th Duke of Roxburghe, by whom she had issue.

- Lord Charles Ashley Spencer-Churchill (1856 – 11 March 1858)

- Lord Augustus Robert Spencer-Churchill (4 July 1858 – 12 May 1859)

- Lady Georgiana Elizabeth Spencer-Churchill (10 St James's Square, St James's, London, 14 May 1860 – 9 February 1906), married 4 June 1883 Richard George Penn Curzon, 4th Earl Howe, by whom she had issue.

- Lady Sarah Isabella Augusta Spencer-Churchill (1865 – 22 October 1929), a war correspondent during the Boer War; married 21 November 1891 Lt. Col. Gordon Chesney Wilson (son of Sir Samuel Wilson, MP)

- Spouse

- Children

Film, television and literary depictions

The character Randolph Churchill has appeared in numerous films and television productions about his son Winston. He is generally portrayed as a cold and distant man, although perhaps was no worse than many other fathers of his time and class.

He was featured in the ITV historical drama series Edward the Seventh as a more natural character, played by Derek Fowlds, sociably similar to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and his other friends. His downfall is represented when he confronted Alexandra, Princess of Wales and demanded her to use her influence with the Prince to stop Lord Aylesford proceeding with a divorce from his wife, Lady Aylesford, after she had planned to elope with Lord Randolph's elder brother, the Marquess of Blandford. He threatens to expose letters from the Prince to Lady Aylesford, so scandalous, so he says, that if they were to be exposed, "the Prince of Wales would never sit on the throne of England." Outraged, the Princess goes to see the Queen, who is equally indignant. The Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, informs the Prince, who is so angry that he challenges Lord Randolph to a duel in the South of France. Eventually, Lord Aylesford does not attempt to seek a divorce from his wife, and Lord Blandford does not elope with Lady Aylesford. Lord Randolph sends a note of apology to the Prince, which is merely acknowledged. Disgraced, Lord Randolph and his wife leave for America.

Other notable appearances include the film Young Winston, in which he was portrayed by Robert Shaw, and the miniseries, Jennie, The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, in which he was portrayed by actor Ronald Pickup, as the English aristocrat who falls in love with the daughter of an American billionaire property developer.

Sir Winston referred to his father's career in several of the last chapters of A History of the English-Speaking Peoples written in Winston's 'wilderness years' in the inter-war years before he was recalled to the cabinet.

Fiction

He is the target of an assassination attempt in the J.M. Barrie novella about a secret society of killers, Better Dead.

See also

References

- ↑ Churchill, Winston C. 1906. Lord Randolph Churchill. 2 vols, Macmillan, London.

- ↑ Frank Harris, My Life and Loves, 1922-27; p. 483

- ↑ McKinstry, Rosebery, pp. 23, 33

- ↑ Rosebery, Ld Randolph, (1906);McKistry, p. 58

- ↑ Churchill, Randolph. "Masonic Papers". The Development of the Craft in England. freemasons-freemasonary.com. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Ted Morgan, Churchill: Young Man in a Hurry, 1874–1915 (1984), p. 23

- 1 2 "Lord Randolph Churchill: Maladies et Mort". Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ↑ Blake, pp. 134-35

- ↑ W S Churchill, Life of Lord Randolph Churchill, 2 vols, chap XIV

- ↑ Blake, p.145

- ↑ Blake, p. 152

- ↑ R.R. James; Blake, pp. 152-53

- ↑ Dictionary of Indian Biography. Ardent Media. 1906. p. 259. GGKEY:BDL52T227UN.

- ↑ Younghusband, Francis (1910). India and Tibet: a history of the relations which have subsisted between the two countries from the time of Warren Hastings to 1910; with a particular account of the mission to Lhasa of 1904. London: John Murray. p. 47.

- ↑ Blake, pp.158-9, 161

- ↑ http://www.matjiesfontein.com/About/index.htm Visit to Matjiesfontein.

- ↑ "RANDOLPH CHURCHILL'S WILL; Details of the Estate Bequeathed to His Wife and Children". New York Times. 5 March 1895.

- ↑ "Measuring Worth – Measures of worth, inflation rates, saving calculator, relative value, worth of a dollar, worth of a pound, purchasing power, gold prices, GDP...". measuringworth.com. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Lord Randolph, was probably historian Rosebery's best book (1906); McKinstry, p.207-8. TLS (1906) described is as "every page, attracts, instructs, inspires".

Archives

- Lord Randolph Churchill (University Library, Cambridge)

Primary sources

- Beach, Lady Victorian (1932). The Life of Sir Michael Hicks Beach. 2 vols.

- Churchill, Peregrine; Mitchell, Julian (1974). Jennie: Lady Randolph Churchill.

- Lord Randolph Churchill. 2 vols. 1906.

- Winston Churchill (1905). Lord Randolph Churchill. London: Odhams Press.

- Volume I (Full text at Archive.org

- Volume II ( Full text at Archive.org

- Winston Churchill (1905). Lord Randolph Churchill. London: Odhams Press.

- Churchill, Randolph S. (1968). Winston S. Churchill. Youth 1874-1900. London.

- Cornwallis-West, Mrs (1908). The Reminiscences of Lady Randolph Churchill.

- Drummond-Wolff, Sir Henry (1908). Rambling Recollections. 2 vols.

- Foster, R F (1988). Lord Randolph Churchill: A Political Life.

- Jennings, Louis J. (1889). Speeches of Lord Randolph Churchill 1880-88. 2 vols.

- Martin, Ralph G. (1972) [1969]. Lady Randolph Churchill. 2 vols.

- Rosebery, Lord (1906). Lord Randolph Churchill.

- Williams, Robin Harcourt (1899). The Salisbury-Balfour Correspondence 1869-1892.

Secondary sources

- Blake, Robert (1985). The Conservative Party from Peel to Thatcher. London. pp. 135–6, 143–5, 148, 151–9, 161, 193, 207.

- Burke, Bernard; Burke, A.P. (1931). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Peerage, Baronetage, the Privy Council and Knightage (89th edition. ed.). London: Burke's Peerage Ltd.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1892). Marlborough. The Complete Peerage of Great Britain and Ireland extant, abeyant and dormant. vol.4. London: George Bell & Sons; Exeter: William Pollard & Co.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1893). The Complete Peerage. vol 5. London: George Bell & Sons; Exeter: William Pollard & Co.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1906). The Complete Baronetage. vol 5. London: William Pollard & Co.

- James, Robert Rhodes (1986) [1959]. Lord Randolph Churchill. London.

- Jenkins, Roy (2010). The Chancellors. London.

- Jenkins, Roy (2009). Churchill. London.

- Leslie, Anita (1969). Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill.

- Leslie, Anita (1972). Edwardians in Love.

- Quinault, R.E. (1976). "The Fourth Party and Conservative Opposition to Bradlaugh 1880-1888". EHR. xci.

- Roberts, Andrew (2009). Salisbury. London.

- Shannon, Richard (1999). Gladstone: Heroic Minister 1865-1898. London. pp. 254–5, 263, 336, 366–72, 399, 429, 433, 444, 459, 563.

- Weston, Corinne C. (1991). "Disunity on the Front Bench 1884". EHR. cvi.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lord Randolph Churchill. |

| Simple English Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Lord Randolph Churchill |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Lord Randolph Churchill |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Lord Randolph Churchill

- Lord Randolph Churchill at Find a Grave

- "Archival material relating to Lord Randolph Churchill". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Randolph Churchill at the National Portrait Gallery, London

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry Barnett |

Member of Parliament for Woodstock 1874–1885 |

Succeeded by Francis William Maclean |

| New constituency | Member of Parliament for Paddington South 1885–1895 |

Succeeded by Sir Thomas George Fardell |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Earl Percy |

Chairman of the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations (jointly with Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Bt) 1884 |

Succeeded by Lord Claud Hamilton |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Kimberley |

Secretary of State for India 1885–1886 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Kimberley |

| Preceded by Sir William Harcourt |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1886 |

Succeeded by George Goschen |

| Preceded by Sir Michael Hicks-Beach, Bt |

Commons Leader of the Conservatives 1886 |

Succeeded by William Henry Smith |

| Preceded by William Gladstone |

Leader of the House of Commons 1886 | |

.svg.png)