London lobsters

- See also: Royal Horse Guards

The London lobsters, Haselrig's Lobsters or just "Lobsters" were the name given to the cavalry unit raised and led by Sir Arthur Haselrig, a Parliamentarian who fought in the English Civil War.

Background

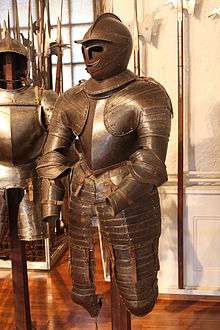

Haselrig was a prominent leader of Parliament's opposition to King Charles, and when the quarrel broke into open warfare he formed this unit, outfitting it with his own money. The unit received its name because, unusually for the time, they were cuirassiers, wearing extensive armour that covered most of their body (except for the lower legs) making them appear somewhat like lobsters. Only two cuirassier regiments were raised during the English Civil War, the other being the Lifeguard of the Earl of Essex, however, individual cavalrymen within other regiments also served in complete armour.[1] Full armour had largely been abandoned at this time, with cuirasses and helmets only worn by some cavalry (harquebusiers), commanders and pike units. The armour of a cuirassier was very expensive; in England, in 1629, a cuirassier's equipment cost four pounds and 10 shillings, whilst a harquebusier's (a lighter type of cavalry) was a mere one pound and six shillings.[2]

War service

The "lobsters" were probably the last unit to fight on English soil wearing full armour, and one of the last in Europe. They were credited with being "the first that made any impression upon the King's horse [the Royalist cavalry], who being unarmed [unarmoured], were not able to bear the shock with them; besides they were secure from hurts of the sword..."[3][4]

Haselrig's regiment formed the heavy cavalry in the army of Sir William Waller. The "lobsters" distinguished themselves at Lansdown on July 5, 1643. [5] However, at the Battle of Roundway Down, on July 13, they met a Royalist cavalry charge at the halt and after a brief clash, retreated in disorder, the Parliamentarian army losing the battle. Though they were defeated the armour they wore apparently served them well; Haselrig was shot three times at Roundway Down, with the bullets apparently bouncing off his armour. After firing a pistol at Haselrig's helmeted head at close range without any effect Richard Atkyns described how he attacked him with his sword, but it too caused no visible damage; Haselrig was under attack from a number of people and only succumbed when Atkyns attacked his unarmoured horse. After the death of his horse Haselrig tried to surrender; but as he fumbled with his sword, which was tied to his wrist, he was rescued. He suffered only minor wounds from his ordeal.[6]

This incident was related to Charles I and elicited one of his rare attempts at humour. The king said that if Haselrig had been as well supplied as he was fortified he could have withstood a siege.

At the Cheriton on March 29, 1644 the unit attacked a royalist regiment of infantry under Sir Henry Bard. Bard's unit had advanced towards the Parliamentary cavalry, but had moved too fast and were no longer in formation with the rest of the Royalist infantry. The Lobsters saw this and Haselrig led 300 of them against Bard's regiment. It was completely destroyed, with all infantry either killed or taken prisoner. Parliament eventually won the battle.[7]

Legacy

Haselrig's regiment was the lineal predecessor of the Royal Horse Guards, ironically for a Parliamentarian foundation one of the household regiments of the British monarchy.

"Sir William Waller having received from London [in June 1643] a fresh regiment of five hundred horse, under the command of sir Arthur Haslerigge, which were so prodigiously armed that they were called by the other side the regiment of lobsters, because of their bright iron shells with which they were covered, being perfect curasseers." [8]

Notes

- ↑ Haythornthwaite, p. 46.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite, pp. 45 and 49.

- ↑ Clarendon, "History of the Rebellion," 1647, vol. 4, p. 111

- ↑ Haythornthwaite, p. 28.

- ↑ Battle of Lansdown bcw-project http://bcw-project.org/military/english-civil-war/west-country/battle-of-lansdown

- ↑ Haythornthwaite, p. 49.

- ↑ "Cheriton 1644" (PDF). English Heritage. p. 8. Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Clarendon, "History of the Rebellion," vol. 4, p. 120

References

- Denton, Barry, Only in Heaven: The Life and Campaigns of Sir Arthur Hesilrige, 1601-1661, Bloomsbury, 1997. ISBN 978-1850756453.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (1983) The English Civil War, An Illustrated History Blandford Press. ISBN 1-85409-323-1.

- Clarendon, Edward Earl of, The history of the rebellion and civil wars in England, 1647 (reprinted 1839).

External links

- Arthur Haselrig

- - An account of the battle (1)

- http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/upload/pdf/Lansdown.pdf