Lemuria (continent)

| Lemuria | |

|---|---|

| Type | Hypothetical lost continent |

| Race(s) | Lemurians |

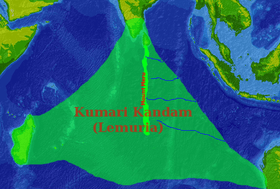

Lemuria /lᵻˈmjʊəriə/[1] is the name of a hypothetical "lost land" variously located in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The concept's 19th-century origins lie in attempts to account for discontinuities in biogeography; however, the concept of Lemuria has been rendered obsolete by modern theories of plate tectonics. Although sunken continents do exist – like Zealandia in the Pacific as well as Mauritia[2] and the Kerguelen Plateau in the Indian Ocean – there is no known geological formation under the Indian or Pacific Oceans that corresponds to the hypothetical Lemuria.[3]

Though Lemuria is no longer considered a valid scientific hypothesis, it has been adopted by writers involved in the occult, as well as by some Tamil writers in India. Accounts of Lemuria differ, but all share a common belief that a continent existed in ancient times and sank beneath the ocean as a result of a geological, often cataclysmic, change, such as pole shift.

Scientific origins

In 1864 the zoologist and biogeographer Philip Sclater wrote an article on "The Mammals of Madagascar" in The Quarterly Journal of Science. Using a classification he referred to as lemurs but which included related primate groups,[4] and puzzled by the presence of their fossils in both Madagascar and India but not in Africa or the Middle East, Sclater proposed that Madagascar and India had once been part of a larger continent (he was correct in this; though in reality this was the supercontinent Pangaea).

The anomalies of the Mammal fauna of Madagascar can best be explained by supposing that ... a large continent occupied parts of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans ... that this continent was broken up into islands, of which some have become amalgamated with ... Africa, some ... with what is now Asia; and that in Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands we have existing relics of this great continent, for which ... I should propose the name Lemuria![4]

Sclater's theory was hardly unusual for his time: "land bridges", real and imagined, fascinated several of Sclater's contemporaries. Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, also looking at the relationship between animals in India and Madagascar, had suggested a southern continent about two decades before Sclater, but did not give it a name.[5] The acceptance of Darwinism led scientists to seek to trace the diffusion of species from their points of evolutionary origin. Prior to the acceptance of continental drift, biologists frequently postulated submerged land masses in order to account for populations of land-based species now separated by barriers of water. Similarly, geologists tried to account for striking resemblances of rock formations on different continents. The first systematic attempt was made by Melchior Neumayr in his book Erdgeschichte in 1887. Many hypothetical submerged land bridges and continents were proposed during the 19th century, in order to account for the present distribution of species.

After gaining some acceptance within the scientific community, the concept of Lemuria began to appear in the works of other scholars. Ernst Haeckel, a Darwinian taxonomist, proposed Lemuria as an explanation for the absence of "missing link" fossil records. According to another source, Haeckel put forward this thesis prior to Sclater (but without using the name "Lemuria").[6] Locating the origins of the human species on this lost continent, he claimed the fossil record could not be found because it sunk beneath the sea.

Other scientists hypothesized that Lemuria had extended across parts of the Pacific oceans, seeking to explain the distribution of various species across Asia and the Americas.

Superseded

The Lemuria theory disappeared completely from conventional scientific consideration after the theories of plate tectonics and continental drift were accepted by the larger scientific community. According to the theory of plate tectonics (the current accepted paradigm in geology), Madagascar and India were indeed once part of the same landmass (thus accounting for geological resemblances), but plate movement caused India to break away millions of years ago, and move to its present location. The original landmass, the supercontinent Gondwana, broke apart; it did not sink beneath sea level.

In 1999, drilling by the JOIDES Resolution research vessel in the Indian Ocean discovered evidence[7] that a large island, the Kerguelen Plateau, was submerged about 20 million years ago by rising sea levels. Samples showed pollen and fragments of wood in a 90-million-year-old sediment. Although this discovery might encourage scholars to expect similarities in dinosaur fossil evidence, and may contribute to understanding the breakup of the Indian and Australian land masses, it does not support the concept of Lemuria as a land bridge for mammals.

In 2013, the study of grains of sand from the beaches of Mauritius led to the conclusion that a similar landmass would have existed between 2,000 and 85 million years ago.[2]

Kumari Kandam

Some Tamil writers such as Devaneya Pavanar have associated Lemuria with Kumari Kandam, a legendary sunken landmass mentioned in the Tamil literature, claiming that it was the cradle of civilization.

In popular culture

Since the 1880s, the legend of Lemuria has inspired many novels, television shows, films and music.

See also

- Atlantis

- Doggerland

- Evolution of lemurs, primate from Madagascar

- Kumari Kandam

- Lost city

- Legends of Mount Shasta

- Mauritia (microcontinent)

- Mu (lost continent)

- Phantom island

- Ramtha

- Jane Roberts

- Thule

References

- ↑ OED

- 1 2 Morelle, Rebecca (2013-02-25). "BBC News - Fragments of ancient continent buried under Indian Ocean". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Navigation News". Frontline.in. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- 1 2 Neild, Ted Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet pp.Harvard University Press (2 Nov 2007) ISBN 978-0-674-02659-9 pp. 38–39

- ↑ Neild, Ted Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet pp.Harvard University Press (2 Nov 2007) ISBN 978-0-674-02659-9 p.38

- ↑ L. Sprague de Camp, Lost Continents, 1954 (First Edition), p. 52

- ↑ "'Lost continent' discovered". BBC News. 27 May 1999. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

Further reading

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi (2004). The Lost Land of Lemuria: Fabulous Geographies, Catastrophic Histories. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24032-4.

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi. (1999). "Catastrophic Cartographies: Mapping the Lost Continent of Lemuria". Representations. 67: 92-129.

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi. (2000). "History at Land’s End: Lemuria in Tamil Spatial Fables". Journal of Asian Studies. 59(3): 575-602.

- Frederick Spencer Oliver, A Dweller on Two Planets, 1905

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)