1912 Lawrence textile strike

| 1912 Lawrence textile strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Massachusetts militiamen with fixed bayonets surround a group of strikers | |||

| Date | January–March 1912 | ||

| Location | Lawrence, Massachusetts | ||

| Goals | 54-hour week | ||

| Methods | Strikes, Protest, Demonstrations | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

| |||

| Arrests, etc | |||

| |||

The Lawrence textile strike was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Prompted by a two-hour pay cut corresponding to a new law shortening the workweek, the strike spread rapidly through the town, growing to more than twenty thousand workers and involving nearly every mill in Lawrence.[1]

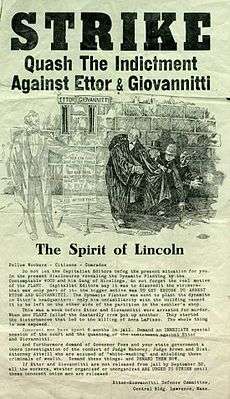

The strike united workers from more than 40 different nationalities.[2] Carried on throughout a brutally cold winter, the strike lasted more than two months, defying the assumptions of conservative trade unions within the American Federation of Labor (AFL) that immigrant, largely female and ethnically divided workers could not be organized. In late January, when a bystander was killed during a protest, IWW organizers Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovannitti were arrested on charges of being accessories to the murder.[2]

IWW leaders Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn came to Lawrence to run the strike. Together they masterminded its signature move, sending hundreds of the strikers' hungry children to sympathetic families in New York, New Jersey, and Vermont. The move drew widespread sympathy, especially after police stopped a further exodus, leading to violence at the Lawrence train station.[2] Congressional hearings followed, resulting in exposure of shocking conditions in the Lawrence mills and calls for investigation of the "wool trust." Mill owners soon decided to settle the strike, giving workers in Lawrence and throughout New England raises of up to 20 percent. Within a year, however, the IWW had largely collapsed in Lawrence.[2]

The Lawrence strike is often referred to as the "Bread and Roses" strike. It has also been called the "strike for three loaves".[3] The phrase "bread and roses" actually preceded the strike, appearing in a poem by James Oppenheim published in The Atlantic Monthly in December 1911. A 1916 labor anthology, The Cry for Justice: An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest by Upton Sinclair, attributed the phrase to the Lawrence strike, and the association stuck. "Bread and roses" has also been attributed to socialist union organizer Rose Schneiderman.[2][4]

History of the event

The background to the strike

Founded in 1845, Lawrence was a flourishing but deeply troubled textile city. By 1900, the mechanization and deskilling of labor in the textile industry enabled factory owners to eliminate skilled workers and employ large numbers of unskilled immigrant workers, the majority of whom were women. Work in a textile mill took place at a grueling pace and the labor was repetitive and dangerous. In addition, a number of children under the age of 14 worked in the mills.[5] Half of the workers in the four Lawrence mills of the American Woolen Company, the leading employer in the industry and the town, were females between the ages of 14 and 18. By 1912, the Lawrence mills at maximum capacity employed about 32,000 men, women, and children.[6] Conditions had grown even worse for workers in the decade before the strike. The introduction of the two-loom system in the woolen mills led to a dramatic speedup in the pace of work. The increase in production enabled the factory owners to lay off large numbers of workers. Those who kept their jobs earned, on average, $8.76 for 56 hours of work.[7][8]

The workers in Lawrence lived in crowded and dangerous apartment buildings, often with many families sharing each apartment. Many families survived on bread, molasses, and beans; as one worker testified before the March 1912 congressional investigation of the Lawrence strike, "When we eat meat it seems like a holiday, especially for the children". The mortality rate for children was 50% by age six; 36 out of every 100 men and women who worked in the mill died before they reached 25. The average life expectancy was 39.[9][10][11][5]

The mills and the community were divided along ethnic lines: most of the skilled jobs were held by native-born workers of English, Irish, and German descent, while Québécois, Italian, Slavic, Hungarian, Portuguese and Syrian immigrants made up most of the unskilled workforce. Several thousand skilled workers belonged, in theory at least, to the American Federation of Labor-affiliated United Textile Workers, but only a few hundred paid dues. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had also been organizing for five years among workers in Lawrence, but also had only a few hundred actual members.[2]

The strike

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On January 1, 1912, a new labor law took effect in Massachusetts reducing the fifty-six-hour workweek to fifty-four hours for women and children. Workers welcomed the two-hour reduction, provided that it did not reduce their weekly take home pay. The first two weeks of 1912, Labor tried to learn how the owners of the mills would deal with the new law.[12] On January 11, a group of Polish women textile workers in Lawrence discovered that their employer at the Everett Mill had reduced about $0.32 from their total wages. They walked out. The next day, January 12, workers in the Washington Mill of the American Woolen Company also found that their wages had been cut. Prepared for the events by weeks of discussion, they walked out, calling “short pay, all out.”[13]

Joseph Ettor of the IWW had been organizing in Lawrence for some time before the strike; he and Arturo Giovannitti of the Italian Socialist Federation of the Socialist Party of America quickly assumed leadership of the strike, forming a strike committee of 56 people—four representatives of fourteen nationalities—which took responsibility for all major decisions.[14] The committee, which arranged for its strike meetings to be translated into 25 different languages, put forward a set of demands: a 15% increase in wages for a 54-hour work week, double time for overtime work, and no discrimination against workers for their strike activity.[15]

The city responded to the strike by ringing the city's alarm bell for the first time in its history; the Mayor ordered a company of the local militia to patrol the streets. The strikers responded with mass picketing. When mill owners turned fire hoses on the picketers gathered in front of the mills,[16] they responded by throwing ice at the plants, breaking a number of windows. The court sentenced 24 workers to a year in jail for throwing ice; as the judge stated, "The only way we can teach them is to deal out the severest sentences".[17] Governor Eugene Foss then ordered out the state militia and state police. Mass arrests followed.[18][19]

At the same time, the United Textile Workers (UTW) attempted to break the strike, claiming to speak for the workers of Lawrence. The striking operatives ignored the UTW. The IWW had successfully united the operatives behind ethnic based leaders. These leaders, members of the strike committee, were able to communicate the message of Joseph Ettor to stage only peaceful demonstrations. Ettor did not consider intimidating operatives trying to enter the mills as breaking the peace. The IWW was successful, even with AFL affiliated operatives, because it defended the grievances of all operatives from all the mills. Conversely, the AFL and the mill owners preferred to keep negotiations between each mill and its own operatives. But in a move that frustrated the UTW, Oliver Christian, national secretary of the Loomfixers Association—an AFL affiliate itself—said he believed John Golden—Massachusetts UTW president—was a detriment to the cause of labor. This statement and missteps by William M. Wood quickly shifted public sentiment to favor the strikers.[20]

A local undertaker and a member of the Lawrence school board attempted to frame the strike leadership by planting dynamite in several locations in town a week after the strike began. He was fined $500 and released without jail time. It later came to light that William M. Wood, president of the American Woolen Company, had made a large payment to the defendant under unexplained circumstances shortly before the dynamite was found.[21][22][23]

The authorities later charged Ettor and Giovannitti as accomplices to murder for the death of striker Anna LoPizzo,[24] likely shot by the police. Ettor and Giovannitti had been 3 mi (4.8 km) away, speaking to another group of workers at the time. They and a third defendant—who had not even heard of either Ettor or Giovannitti at the time of his arrest—were held in jail for the duration of the strike and several months thereafter.[25] The authorities declared martial law,[26] banned all public meetings and called out twenty-two more militia companies to patrol the streets.

The IWW responded by sending Bill Haywood, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and a number of other organizers to Lawrence. Haywood participated little in the daily affairs of the strike. Instead, he set out for other New England textile towns in an effort to raise funds for the strikers in Lawrence. This tactic proved very successful. The union established an efficient system of relief committees, soup kitchens, and food distribution stations, while volunteer doctors provided medical care. The IWW raised funds on a nationwide basis to provide weekly benefits for strikers and dramatized the strikers' needs by arranging for several hundred children to go to supporters' homes in New York City for the duration of the strike. When city authorities tried to prevent another 100 children from going to Philadelphia on February 24 by sending police and the militia to the station to detain the children and arrest their parents, the police began clubbing both the children and their mothers while dragging them off to be taken away by truck; one pregnant mother miscarried. The press, there to photograph the event, reported extensively on the attack. Moreover, when the women and children were taken to the Police Court, most of them refused to pay the fines levied and opted for a jail cell, some with babies in arms.[27]

The police action against the mothers and children of Lawrence attracted the attention of the nation, and in particular that of Helen Herron Taft, the wife of President Taft. Soon after, both the House and Senate set out to investigate the strike. In the early days of March a special house committee heard testimony from some of the strikers' children, various city, state and union officials. In the end both House and Senate published reports detailing the conditions at Lawrence.[28][8]

The national attention had an effect: the owners offered a 5% pay raise on March 1; the workers rejected it. American Woolen Company agreed to most of the strikers' demands on March 12, 1912. The strikers had demanded an end to the Premium System, where a portion of their earnings were subject to month-long production and attendance standards. The mill owners only concession on this point was to change the award of the premium from once every four weeks to once every two weeks. The rest of the manufacturers followed by the end of the month; other textile companies throughout New England, anxious to avoid a similar confrontation, followed suit.[1]

The aftermath

Ettor and Giovannitti remained in prison even after the strike ended. Haywood threatened a general strike to demand their freedom, with the cry "Open the jail gates or we will close the mill gates". The IWW raised $60,000 for their defense and held demonstrations and mass meetings throughout the country in their support; the authorities in Boston, Massachusetts arrested all of the members of the Ettor and Giovannitti Defense Committee. Fifteen thousand Lawrence workers went on strike for one day on September 30 to demand that Ettor and Giovannitti be released. Swedish and French workers proposed a boycott of woolen goods from the United States and a refusal to load ships going to the U.S.; Italian supporters of the Giovannitti men rallied in front of the U.S. consulate in Rome.[29]

In the meantime, Ernest Pitman—a Lawrence building contractor who had done extensive work for the American Woolen Company—confessed to a district attorney that he had attended a meeting in the Boston offices of Lawrence textile companies where the plan to frame the union by planting dynamite had been made. Pitman committed suicide shortly thereafter when subpoenaed to testify. Wood—the owner of the American Woolen Company—was formally exonerated.[30][31]

When the trial of Ettor and Giovannitti, and a third defendant—Giuseppe Caruso, accused of firing the shot that killed the picketer—began in September 1912 in Salem, Massachusetts before Judge Joseph F. Quinn, the three defendants were kept in steel cages in the courtroom. Witnesses testified without contradiction that Ettor and Giovannitti were miles away while Caruso, the third defendant, was at home eating supper at the time of the killing.[25][29]

Ettor and Giovannitti both delivered closing statements at the end of the two-month trial. In Joe Ettor's closing statement, he turned and faced the District Attorney:

"Does Mr. Ateill believe for a moment that...the cross or the gallows or the guillotine, the hangman's noose, ever settled an idea? It never did. If an idea can live, it lives because history adjudges it right. And what has been considered an idea constituting a social crime in one age has in the next age become the religion of humanity. Whatever my social views are, they are what they are. They cannot be tried in this courtroom." [32]

All three defendants were acquitted on November 26, 1912.[33]

The strikers, however, lost nearly all of the gains they had won in the next few years. The IWW disdained written contracts, holding that such contracts encouraged workers to abandon the daily class struggle. The mill owners proved more persistent, slowly chiseling away at the improvements in wages and working conditions, while firing union activists and installing labor spies to keep an eye on workers. A depression in the industry, followed by another speedup, led to further layoffs.[29]

By that time, the IWW had turned its attention to supporting the silk industry workers in Paterson, New Jersey. The Paterson strike ended in defeat.

Casualties

The strike had at least three casualties:[34]

- Anna LoPizzo, an Italian immigrant who was shot in the chest during a clash between strikers and police[35][36]

- John Ramey, a Syrian youth who was bayoneted in the back by the militia[37][38][39]

- Jonas Smolskas, a Lithuanian immigrant beaten to death several months after the strike ended for wearing a pro-labor pin on his lapel[40][41]

See also

- Bread and Roses Heritage Festival in Lawrence

- Carmela Teoli, a teenage mill worker who testified before Congress about being scalped by a machine

- William M. Wood, co-founder of the American Woolen Company

- Ralph Fasanella, an artist who depicted the strike in a series of paintings

- Murder of workers in labor disputes in the United States

References

- 1 2 Sibley, Frank P. (March 17, 1912). "Lawrence's Great Strike Reviewed: Cost $3,000,000, Lasted Nine Weeks--27,000 Workers Out". The Boston Daily Globe. (subscription required (help)).

Tomorrow morning ends officially the strike of the textile operatives at Lawrence, in nearly all the mills.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Weir, Robert E. (2013). Workers in America: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 418–420. ISBN 9781598847185.

- ↑ Milkman, Ruth (2013). Women, Work, and Protest: A Century of U.S. Women's Labor History. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 9781136247682.

- ↑ Zwick, Jim (2003). "Behind the Song: Bread and Roses". Sing Out! The Folk Song Magazine. 46: 92–93. ISSN 0037-5624. OCLC 474160863.

- 1 2 Moran, William (2002). "Fighting for Roses". The Belles of New England: The Women of the Textile Mills and the Families Whose Wealth They Wove. Macmillan. p. 183. ISBN 9780312301835.

Elizabeth Shapleigh, a physician in the city, made a mortality study among mill workers and found that one-third of them, victims of the lint-filled air of the mills, died before reaching the age of 25.

- ↑ Foner, Philip (1965). History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 4. New York: International Publishers. p. 307. LCCN 47-19381.

- ↑ Forrant, Robert (2014). The Great Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912: New Scholarship on the Bread & Roses Strike (PDF). Baywood Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 9780895038647.

- 1 2 Neill, Charles P. (1912). Report on Strike of Textile Workers in Lawrence, Mass. in 1912 (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 19.

- ↑ Neill Report (1912), "Housing and Rents", pp. 23-25

- ↑ Wertheimer, Barbara M. (1977). We were there: the story of working women in America. Pantheon Books. p. 358. ISBN 9780394495903.

- ↑ Forrant (2014), p. 4

- ↑ Watson, Bruce (2005). Bread & Roses: Mills, Migrants, and the Struggle for the American Dream. New York: Penguin Group. p. 12.

- ↑ Ross, Robert F.S. (March 2013). "Bread and Roses: Women Workers and the Struggle for Dignity and Respect". Working USA: The Journal of Labor & Society. Immanuel News and Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 16: 59–68.

- ↑ Watson (2005), p. 59

- ↑ Watson (2005), p. 71

- ↑ Forrant, Robert (2013). Lawrence and the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike. Arcadia Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 9781439643846. (See photograph)

- ↑ Watson (2005), p. 55

- ↑ "FOSS URGES ARMISTICE. Asks Strikers to Return and Mill Owners to Pay Old Wages". The New York Times. January 29, 1912.

- ↑ Neill Report, p. 15

- ↑ Ayers, Edward L. (2008). American Passages: A History of the United States. Cengage Learning. p. 616. ISBN 9780547166292.

- ↑ Watson (2006), pp. 109-110, 222, 249-250

- ↑ "ON TRIAL FOR 'PLANT' IN LAWRENCE STRIKE; Wm. Wood, Boston Manufacturer, and Others Face Jury in Dynamite Case". The New York Times. May 20, 1913.

- ↑ "Approval In Wood's Name". The Boston Daily Globe. May 24, 1913. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years, Fred W. Thompson & Patrick Murfin, 1976, page 56.

- 1 2 "Lawrence Police Break Up Attempt at Parade". The Boston Daily Globe. November 27, 1912. (subscription required (help)).

All three, after imprisonment of nearly ten months, are now free.

- ↑ Forrant (2013), p. 50

- ↑ Watson, p. 291 (see headlines); see also p. 186

- ↑ The strike at Lawrence, Mass.: Hearings before the Committee on Rules of the House of Representatives on House Resolutions 409 and 433, March 2-7, 1912. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1912.

- 1 2 3 Kornbluh, Joyce L. (2011). Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology. PM Press. pp. 160, 163. ISBN 9781604864830.

- ↑ Forrant (2014), p. 41

- ↑ "Wood Found Not Guilty By Jury". The Boston Daily Globe. June 8, 1913. (subscription required (help)).

An interesting problem growing out of the trial, which remains unsettled, is the charge by Morris Shuman, one of the jurors, that someone tried to bribe him...telling him that he could get a good job with the American Woolen Company or $200 if he would 'vote right.'

- ↑ Ebert, Justus (1913). The Trial of a New Society. Cleveland: I.W.W. p. 38.

- ↑ "ACQUITTED, THEY KISSED.; Ettor and Giovannitti, and Caruso Thanked Judge and Jury". The New York Times. November 27, 1912.

- ↑ "Bread and Roses Strike of 1912: Two Months in Lawrence, Massachusetts, that Changed Labor History: Remembering the Fallen". Digital Public Library of America.

- ↑ Arnesen, Eric (2007). Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. pp. 793–794. ISBN 9780415968263.

- ↑ Neill Report (1912), p. 44

- ↑ Forrant (2013), p. 69 (see photograph)

- ↑ Sibley, Frank P. (January 31, 1912). "DEAD NOW NUMBER TWO--ETTOR AND HIS RIGHT HAND MAN ARRESTED ON MURDER CHARGE Each Accused of Being Accessory To Killing of Lopizzo Woman. State Police Take Them in Custody in Middle of Night and Bail is Refused. John Ramey, Syrian Youth, Bayoneted in Back By Soldier, Dies of His Wounds.". The Boston Daily Globe. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Neill Report (1912), p. 45

- ↑ Watson (2006), p. 232

- ↑ Cole, Caroline L. (September 1, 2002). "Lawrence Strike Hero Brought Out of History's Shadows". The Boston Globe. (subscription required (help)).

Further reading

- Cole, Donald B. Immigrant City: Lawrence, Massachusetts 1845-1921. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963.

- Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. Revised Edition. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

- Bread and Roses, Too a young adult historical novel about the Lawrence strike by Katherine Paterson

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lawrence Textile Strike. |

- Bread and Roses Centennial 1912–2012 Extensive collection of background information, photos, primary documents, bibliographies, testimonies, events, and more.

- Testimony of Camella Teoli before Congress

- Lawrence Strike of 1912 on Marxists.org

- Resources for teaching about the Lawrence Strike in K-12 Classrooms listed on the Zinn Education Project website