Laccase

| Laccase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 1.10.3.2 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 80498-15-3 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / EGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Laccases (EC 1.10.3.2) are copper-containing oxidase enzymes found in many plants, fungi, and microorganisms. Laccases act on phenols and similar molecules, performing one-electron oxidations, which remain poorly defined. It is proposed that laccases play a role in the formation of lignin by promoting the oxidative coupling of monolignols, a family of naturally occurring phenols.[1] Laccases can be polymeric, and the enzymatically active form can be a dimer or trimer. Other laccases, such as those produced by the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus, play a role in the degradation of lignin, and can therefore be classed as lignin-modifying enzymes.[2]

Laccases require oxygen as a second substrate for their enzymatic action.

Spectrophotometry can be used to detect laccases, using the substrates ABTS, syringaldazine, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol, and dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine. Activity can also be monitored with an oxygen sensor, as the oxidation of the substrate is paired with the reduction of oxygen to water.

Laccase was first studied by Gabriel Bertrand[3] in 1894[4] in the sap of the Chinese lacquer tree, where it helps to form lacquer, hence the name laccase.

Laccases can catalyze ring cleavage of aromatic compounds.[5]

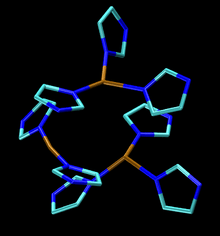

Copper binding

The copper bound by laccase is bound in several sites: type 1, type 2, and/or type 3. The ensemble of types 2 and 3 copper is called a trinuclear cluster (see figure). Type 1 copper is available to action of solvents, such as water. It can be displaced by mercury, substituted by cobalt or removed via a copper complexone. Removal of type 1 copper causes a decrease in laccase activity. Cyanide can remove all copper from the enzyme, and re-embedding with type 1 and type 2 copper has been shown to be impossible. Type 3 copper, however, can be re-embedded back into the enzyme.

Inhibition

Laccase can be inhibited by small ions such as: azide, halides, cyanide, and fluoride. These ions bind to type 2 and type 3 copper and disrupts electron transfer via copper centers, therefore reduces activity. Metal ions, fatty acids, hydroxyglycine, and kojic acid can also inhibit laccase by causing amino acid residue changes, conformational changes or copper chelation.[6]

Applications and potential utility

Laccases have been examined as the cathode in enzymatic biofuel cells. They can be paired with an electron mediator to facilitate electron transfer to a solid electrode wire.[7] Laccases are some of the few oxidoreductases commercialized as industrial catalysts. The enzymes can be used for textile dyeing/textile finishing, wine cork making, teeth whitening, and many other industrial, environmental, diagnostic, and synthetic uses.[8] Laccases can be used in bioremediation. Protein ligand docking can be used to predict the putative pollutants that can be degraded by laccase.[9]

Activity of Laccase in Wheat Dough

Laccases have the potential to cross link food polymers such as proteins and nonstarch polysaccharides in dough. In non starch polysaccharides, such as arabinoxylans (AX), laccase catalyzes the oxidative gelation of feruloylated arabinoxylans by dimerization of their ferulic esters.[10] These cross links have been found to greatly increased the maximum resistance and decreased extensibility of the dough. The resistance was increased due to the crosslinking of AX via ferulic acid and resulting in a strong AX and gluten network. Although laccase is known to cross link AX, under the microscope it was found that the laccase also acted on the flour proteins. Oxidation of the ferulic acid on AX to form ferulic acid radicals increased the oxidation rate of free SH groups on the gluten proteins and thus influenced the formation of S-S bonds between gluten polymers.[11] Laccase is also able to oxidize peptide bound tyrosine, but very poorly.[11] Because of the increased strength of the dough, it showed irregular bubble formation during proofing. This was a result of the gas (carbon dioxide) becoming trapped within the crust and could not diffuse out (like it would have normally) and causing abnormal pore size.[10] Resistance and extensibility was a function of dosage, but at very high dosage the dough showed contradictory results: maximum resistance was reduced drastically. The high dosage may have caused extreme changes in structure of dough, resulting in incomplete gluten formation. Another reason is that it may mimic overmixing, causing negative effects on gluten structure. Laccase treated dough had low stability over prolonged storage. The dough became softer and this is related to laccase mediation. The laccase mediated radical mechanism creates secondary reactions of FA-dervived radicals that result in breaking of covalent linkages in AX and weakening of the AX gel.[10]

Use in food industry

The hazing effect is a quality defect in beer. It is characterized by “cloudiness” in the final product. Laccase can be added to the wort or at the end of the process to remove the polyphenols that may still remain in beer. The polyphenol complexes, formed by laccases, can be separated via filtration and removes probability of the hazing effect from occurring.

Laccase can also remove excess oxygen in beer and increase the storage life of beer.

In fruit juices such as apple and grape, excess oxidation of phenolics causes negative effects on the taste, color, odour and mouthfeel. Laccase has been proposed to delay the oxidation of polyphenols and stabilize the juice.

References

- ↑ Edward I. Solomon, Uma M. Sundaram, Timothy E. Machonkin "Multicopper Oxidases and Oxygenases" Chemical Reviews, 1996, Volume 96, pp. 2563-2606.

- ↑ Cohen, R.; Persky, L.; Hadar, Y. (2002). "Biotechnological applications and potential of wood-degrading mushrooms of the genus Pleurotus" (PDF). Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 58 (5): 582–94. doi:10.1007/s00253-002-0930-y. PMID 11956739.

- ↑ Gabriel Bertrand on isimabomba.free.fr (French)

- ↑ Science and civilisation in China: Chemistry and chemical ..., Volume 5, Part 4 By Joseph Needham, Ping-Yü Ho, Gwei-Djen Lu and Nathan Sivin, p. 209

- ↑ Claus, H. (2004) Laccases: structure, reactions, distribution. Micron 35, 93-96.

- ↑ Alcalde, M. (2007) Laccases: Biological functions, molecular structure and industrial applications. In J. Polaina & A.P. MacCabe (Eds.), Industrial Enzymes (461-476). Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/content/x36265261wun1n36/fulltext.pdf

- ↑ Wheeldon, I.R.; Gallaway, J.W.; Calabrese Barton, S.; Banta, S. (2008). "Bioelectrocatalytic hydrogels from electron-conducting metallopolypeptides coassembled with bifunctional enzymatic building blocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 105 (40): 15275–15280. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805249105. PMC 2563127

. PMID 18824691.

. PMID 18824691. - ↑ Xu, Feng (Spring 2005). "Applications of oxidoreductases: Recent progress". Industrial Biotechnology. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 1 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1089/ind.2005.1.38. ISSN 1931-8421.

- ↑ Suresh PS, Kumar A, Kumar R, Singh VP (2008). "An in silico [correction of insilico] approach to bioremediation: laccase as a case study". J. Mol. Graph. Model. 26 (5): 845–9. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2007.05.005. PMID 17606396.

- 1 2 3 Selinheimo, E. (2008) Tyrosinase and laccase as novel crosslinking tools for food biopolymers. VTT Publications, 693, 114 – 162.

- 1 2 Selinheimo, E., Autio, K., Kruus, K. & Buchert, J. (2007) Elucidating the Mechanism of Laccase and Tyrosinase in Wheat Bread Making. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 55, 6357-6365.

External links

- BRENDA

- Laccase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)