Korçë

| Korçë | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | ||||||||

Korça Photomontage | ||||||||

| ||||||||

Korçë | ||||||||

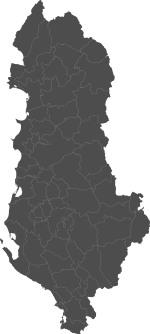

| Coordinates: 40°37′N 20°46′E / 40.617°N 20.767°ECoordinates: 40°37′N 20°46′E / 40.617°N 20.767°E | ||||||||

| Country |

| |||||||

| County | Korçë | |||||||

| Government | ||||||||

| • Mayor | Sotiraq Filo (SP) | |||||||

| Area | ||||||||

| • Municipality | 805.99 km2 (311.19 sq mi) | |||||||

| Elevation | 850 m (2,790 ft) | |||||||

| Population (2011) | ||||||||

| • Municipality | 75,994 | |||||||

| • Municipality density | 94/km2 (240/sq mi) | |||||||

| • Administrative Unit | 51,152 | |||||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |||||||

| Postal Code | 7001–7004 | |||||||

| Area Code | (0)82 | |||||||

| Vehicle registration | AL | |||||||

| Website | Official Website | |||||||

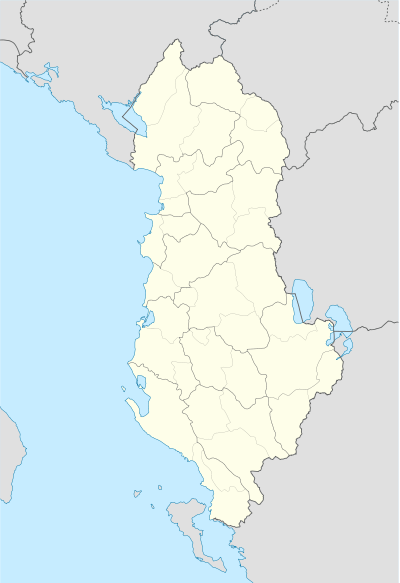

Korçë (IPA: [kɔɾtʃə]; (definite Albanian form: Korça, other names see below) is a city and municipality in southeastern Albania, and the seat of Korçë County. It was formed at the 2015 local government reform by the merger of the former municipalities Drenovë, Korçë, Lekas, Mollaj, Qendër Bulgarec, Vithkuq, Voskop and Voskopojë, that became municipal units. The seat of the municipality is the city Korçë.[1] The total population is 75,994 (2011 census), in a total area of 805.99 km2 (311.19 sq mi).[2] The population of the former municipality at the 2011 census was 51,152.[3] It is the sixth largest city in Albania. It stands on a plateau some 850 m (2,789 ft) above sea level, surrounded by the Morava Mountains.

Name

Korçë is named differently in other languages: Aromanian: Curceaua or Corceao; Bulgarian and Macedonian form: Горица, Goritsa; Greek: Κορυτσά, Korytsá; Italian: Coriza; Turkish: Görice; Romanian: Korça. The current name is obviously of Slavic origin. The name "Gorica", meaning hill in Slavic, is a very common toponym in Albania and Slavic countries.

History

Antiquity

The Copper Age lasted from 3000 BC to 2100 BC. Mycenean pottery was introduced in the plain of Korçë during the late Bronze Age (Late Helladic IIIc),[4] and has been claimed that the tribes living in this region before the Dark Age migrations, probably spoke a northwestern Greek dialect.[5] The area was on the border between Illyria and Epirus and according to a historical reconstruction was ruled by an Illyrian dynasty until 650 BC, while after 650 BC a Chaonian dynasty.[6][7][8] During this period the area was inhabited by Greek tribes of the northwestern (Epirote) group, possibly Chaonians or Molossians, which were two of the three major Epirote tribes inhabiting the region of Epirus.[9] Archaeologists have found a gravestone of the 2nd or 3rd century AD depicting two Illyrian blacksmiths working iron on an anvil near modern Korçë.[10]

Middle Ages and Ottoman rule

From the 13th century it was a small settlement called Episkopi (Greek: Επισκοπή, "bishopric").[11] The modern town dates from the 1480s, when Iljaz Hoxha, during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II, developed Korçë.[12] The Ottoman occupation began in 1440, and after Hoxha's role in the siege of Constantinople, in 1453; he was awarded the title, 'Iljaz Bey Mirahor'. Korçë was a sandjak of the Manastir Vilayet in the Ottoman Empire as Görice.[13] The city started to flourish when the nearby town of Moscopole was raided by the Albanian troops of Ali Pasha at 1788.[14] [15]

In the late 1880s Gjerasim Qiriazi began his Protestant mission in the city. He and fellow members of the Kyrias family established Albanian speaking institutions in Korçë, with his sister Sevasti Qiriazi founding the first Albanian girls school in 1891.

20th century

Early 20th century

Ottoman rule over Korçë lasted until 1912; although the city and its surroundings were supposed to become part of the Principality of Bulgaria according to the Treaty of San Stefano in 1878, the Treaty of Berlin of the same year returned the area to Ottoman rule.[16] In 1910 the Orthodox Alliance of Korçë led by Mihal Grameno proclaimed the establishment of an Albanian church, but the Ottoman authorities refused to recognize it.[17] Korçë's proximity to Greece, which claimed the entire Orthodox population as Greek, led to its being fiercely contested in the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913. Greek forces captured Korçë from the Ottomans on 6 December 1912 and afterwards proceeded to imprison the Albanian nationalists of the town.[18] Its incorporation into Albania in 1913 was disputed by Greece, who claimed it as part of a region called 'Northern Epirus', and resulted in a rebellion by the local Greek population that asked the intervention of the Greek army.[19] This rebellion was initially suppressed by the Dutch commanders of the Albanian gendarmerie, that consisted of 100 Albanians led by Themistokli Gërmenji, as a result the local Greek-Orthodox bishop Germanos and other members of the town council were arrested and expelled by the Dutch.[20][21] However, under the terms of the Protocol of Corfu (May 1914), the city became part of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus inside the borders of the principality of Albania,[22] while on 10 July 1914 the Greek Northern Epirote forces took over the city.[23]

In October 1914 the city came again under Greek administration. During the period of the National Schism (1916) a local revolt broke out and with military and local support Korçë came under the control of Eleftherios Venizelos' Movement of National Defence, overthrowing the royalist forces.[24] However, due to developments in the Macedonian Front of World War I the city came soon under French control (1916–1920). During this time fourteen representatives of Korçë and Colonel Descoins signed a protocol that proclaimed the Autonomous Albanian Republic of Korçë under the military protection of the French army and with Themistokli Gërmenji as president.[20][25] It ultimately remained part of Albania, as determined by the International Boundary Commission, which affirmed the country's 1913 borders.

World War II

Italian forces occupied Korçë in 1939, along with the rest of the country. During the Greco-Italian War it became the main forward base of the Italian air force. Nevertheless, the city came under the control of the advancing Greek forces, on November 22, 1940, during the first phase of the Greek counter-offensive.[26] Korçë remained under Greek control until the German invasion of Greece in April 1941. After Italy's withdrawal from the war in 1943, the Germans occupied the town until October 24, 1944.

During the occupation, the city became a major centre of Communist-inspired resistance to the Axis occupation of Albania. The establishment of the Albanian Party of Labour—the Communist Party—was formally proclaimed in Korçë in 1941. Albanian rule was restored in 1944 following the withdrawal of German forces.

Socialist era

The period of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania was a difficult time in the region. President Enver Hoxha targeted the rich, despite the fact that they had fought for the creation of the communist state by fighting against the Fascist occupations. Right after World War II many people fled to Boston, United States joining a community of the Albanian-Americans, who had previously emigrated there.

After 1990 Korçë was one of the six cities where the New Democratic Party won all the constituencies. Popular revolts in February 1991 ended with the tearing down of Hoxha's statue.

Post-communism and rebirth

After the fall of communism, the city fell into disregard in many aspects. However following the 2000s, the city experienced a makeover as main streets and alleys started to be reconstructed, locals began to renovate their historic villas, a calendar of events was introduced, building façades painted, and city parks reinvigorated. The European Union is financing the renovation of the Korca Old Bazaar while the city centre was redesigned, and a watch tower constructed.

Climate

Korçë has a transitional Mediterranean climate (or continental Mediterranean climate) with high temperature amplitudes. The hottest month is August (25 °C (77 °F)) while January (2 °C (36 °F)) is the coldest. The city receives around 710 millimeters (28 in) annual precipitation with summer minimum and winter maximum, which makes it easily the driest major city in generally humid Albania, owing to the rain shadow of the coastal mountains. The temperatures in Korçë generally remain cooler than the western part of Albania, due to the middle altitude of the plain in which it is situated, but it receives about 2300 hours of solar radiation per year, so its temperatures are higher than those in Northeastern Albania. Temperatures can still reach up to 40 °C (104 °F) or higher on occasions.

| Climate data for Korçë | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4 (40) |

7 (45) |

8 (46) |

14 (57) |

19 (66) |

24 (75) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

22 (72) |

17 (62) |

10 (50) |

6 (43) |

16 (60) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3 (27) |

−2 (29) |

−1 (30) |

4 (39) |

9 (48) |

12 (53) |

14 (57) |

15 (59) |

11 (51) |

7 (44) |

3 (38) |

−1 (31) |

6 (42) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58 (2.3) |

89 (3.5) |

50 (2) |

53 (2.1) |

99 (3.9) |

30 (1) |

18 (0.7) |

10 (0.4) |

50 (2) |

81 (3.2) |

132 (5.2) |

53 (2.1) |

719 (28.3) |

| Source: Weatherbase [27] | |||||||||||||

Religion

For centuries Korçë has been an important religious centre for Orthodox Christians and Muslims.[28] The city is host to a large Orthodox community. There is also a large Sunni community in and around the city. A Bektashi community is also present in the city. The main centre of the Bektashis of the area is the Turan Tekke.

The city was initially part of the Metropolis of Kastoria (15th century), but in the early 17th century became the seat of an Orthodox bishop and in 1670 was elevated to metropolitan bishopric.[29][30] The city remained entirely Christian until the first half of the 16th century.[30] The Orthodox cathedral of saint George, a significant landmark in the city, was demolished by the authorities of the People's Republic of Albania during the atheistic campaign.[31]

Islam entered the city in the 15th century through Iljaz Hoxha, an Albanian jannissary, who actively participated in the Fall of Constantinople.[32] One of the oldest mosques in Albania was built by Iljaz Hoxha in 1484, the Iliaz Mirahori Mosque.[33]

Museums and culture

Korçë is referred to as the city of museums. The National Museum of Medieval Art of Albania has rich archives of ca. 6500 icons and 500 other objects in textile, stone and metal. The National Museum of Archeology is located in Korçë. The first Albanian School as well as the residence and gallery of painter Vangjush Mio function as museums. The Bratko Museum and the Oriental Museum are also located in the city.

Korçë has a city theatre, the Andon Zako Çajupi Theatre, which started its shows in 1950 and has been working uninterruptedly since.[34]

Education

The first school, a Greek language school, in the city was established in 1724 with the support of residents of nearby Vithkuq.[35][36] This school was destroyed during the Greek War of Independence but it reopened in 1830. In 1857 a Greek school for girls was operating in the city.[37] During the 19th century various local benefactors such as Ioannis Pangas donated money for the promotion of Greek education and culture in Korçë, such as the Bangas Gymnasium.[38][39] Similarly, kindergartens, boarding and urban schools, were also operating in the city during this period.[35] Under these developments, a special community fund, named the Lasso fund, was established in 1850 by the local Orthodox bishop Neophytos,[40] in order to support Greek cultural activity in Korçë.[41]

At the end of the 19th century local Albanians expressed a growing need to be educated in their native language.[42] The Albanian intellectual diaspora from Istanbul and Bucharest initially tried to avoid antagonism towards the notables of Korçë, who were in favor of Greek culture. Thus they suggested the introduction of Albanian language in the existing Greek Orthodox schools, a proposal which was discussed with the local bishop and the city council; the Demogeronteia (Greek: Δημογεροντεία) and finally rejected by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[43] As a result, the first Albanian language school was established in 1887 by the Drita (English: Light) organization and funded by notable local individuals. Its first director was Pandeli Sotiri.[43][44] Naim Frashëri, the national poet of Albania played a great role in the opening of the school. As a high-ranking statesman in the ministry of education of the Ottoman Empire he managed to get official permission for the school. The Ottoman authorities gave permission only for Christian children to be educated in Albanian, but the Albanians did not follow this restriction and allowed also Muslim children to attend. As a result, the school was closed in 1902 by the Ottoman authorities.[45]

The school was followed by Albania's first school for girls in 1891. It started by Gjerasim Qiriazi and was later run by his sisters, Sevasti and Parashqevi Qiriazi, together with Polikseni Luarasi (Dhespoti). Later collaborators were the Rev. & Mrs. Grigor Çilka and Rev & Mrs. Phineas Kennedy of the Congregational Mission Board of Boston.

When the city was under French administration in 1916 (the Republic of Korçë), Greek schools were closed and 200 Albanian and French language schools were opened. A few months later Greek schools were reopened as a reward and result of Greece's adhesion to the Entente alliance, part of which was France.[46] Particularly relevant was the opening in 1917 of the Albanian National Lyceum.

The city is home to Fan Noli University, founded in 1971, which offers several degrees in the humanities, sciences and business. The University includes a school in Agriculture, Teaching, Business, Nursing, and Tourism.

After the collapse of the Socialist Republic, part of the local communities expressed a growing need to revive their cultural past, in particular with the reopenning of Greek schools.[35] In April 2005 the first bilingual Greek-Albanian school opened in Korçë after 60 years of prohibition of Greek education.[47] In addition, a total of 17 Greek language institutes are functioning in the city.[35]

Economy

During the 20th century, Korçë gained a substantial industrial capacity in addition to its historic role as a commercial and agricultural centre. The plateau on which the city stands is highly fertile and is one of Albania's main wheat-growing areas. Local industries include the manufacture of knitwear, rugs, textiles, flour-milling, brewing, and sugar-refining. Deposits of lignite coal are mined in the mountains nearby such as Mborje-Drenovë. The city is home to the nationally famous Birra Korça.

According to official reports the city enjoys one of the lowest unemployment rates in the country. The majority of foreign investment comes from Greeks, as well as joint Albanian-Greek enterprises.[35][48]

Sport

- The football club is KS Skënderbeu Korçë, Albanian Champions in 1933 and recently, in 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016.

Panorama

Notable people from Korçë

In alphabetical order by last name:

- Thoma Abrami, poet and activist of the Albanian National Awakening

- Iosiph Adamidis, politician

- Servet Tefik Agai, football player

- Lejla Agolli, composer

- Anthony Athanas, multi-millionaire restaurateur and philanthropist.

- Anastas Avramidhi-Lakçe (1821–1890), businessman and benefactor.

- Olsi Baze, politician

- Dhimitër Berati, signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence.

- Ridvan Bode, politician

- Pandeli Cale, rilindas and signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence

- Epameinondas Charisiadis, revolutionary and politician

- Mariela Cingo, pianist

- Dhimiter Çani, sculptor

- Kostika Çollaku, composer

- Christo Dako, minister of education and political activist

- Visar Dodani, journalist and activist of the Albanian National Awakening.

- Milo Duçi, publisher and entrepreneur

- Pandeli Evangjeli, twice Prime Minister of Albania

- Pavlina Evro, mid-distance runner, winner of the 1500 meter race at the "Grand Prix" International Athletic Meeting in Nice (France)

- Kristo Floqi, patriot, playwright, politician, and lawyer

- Thanas Floqi, rilindas and signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence

- Eshref Frashëri, politician

- Stivi Frashëri, footballer

- Llazar Fundo, member of the Albanian Communist Party during WWII.

- Pandi Geço, geographer

- Themistokli Gërmenji, nationalist and guerrilla fighter

- Mihal Grameno, rilindas, freedom fighter along Çerçiz Topulli, journalist, and writer.

- Eduard Halimi, politician

- Gertin Hoxhalli, footballer

- Dhimitër Ilo, patriot

- Spiro Ilo, signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence

- Ergys Kaçe, footballer

- Jani Kaçi, footballer

- Alfred Karamuço, judge

- Kristo Kirka, nationalist

- Idhomene Kosturi, former Prime Minister of Albania

- Kostaq Kota, politician, former Prime Minister of Albania

- Panteleimon Kotokos (1890–1969), Greek Orthodox cleric, bishop of Gjirokastër (1937–1941).

- Koçi Bey, 17th-century high-ranking Ottoman bureaucrat

- Ermal Kuqo, basketball player, member of the Albanian national basketball team

- Pandi Laço, journalist, songwriter and presenter

- Sabien Lilaj, footballer

- Loni Logori, entrepreneur and poet

- Rita Marko, communist and politician, member of the Politburo

- Devis Mema, footballer

- Gjon Mili, fotographer

- Vangjush Mio, painter

- Thimi Mitko, nationalist and folklorist

- Dhimitër Orgocka, actor and screenplayer, People's Artist of Albania

- Thoma Orollogaj, Minister of Justice of Albania, and Balli Kombëtar leader.

- Petros Orologas (1892–1958), journalist and newspaper publisher

- Tefik Osmani, football soccer player, capped with the Albania

- Ioannis Pangas (1814–1895), entrepreneur and benefactor.

- Niko Peleshi, politician

- Pilo Peristeri, politiian

- Servet Pëllumbi, politician

- Marigo Posio, nationalist

- Foqion Postoli, novelist

- Aleko Prodani, actor

- Alma Qeramixhi, athlete

- Bleona Qereti, singer

- Pandi Raidhi, actor

- Leonidas Sabanis, weightlifter

- Aristotel Samsuri, football player

- Llazi Sërbo, film and stage actor

- Bledi Shkëmbi, footballer

- Behar Shtylla, diplomat and Foreign Minister from 1953 to 1970

- Konstantinos Skenderis, author and politician

- Stavro Skëndi, historian and linguist

- Euclidis Somos, politician

- Koulis Sterikas, painter.

- Donald Suxho, volleyball player

- Arthur Tashko, painter

- Koço Theodhosi, politician

- Roland Trebicka, actor

- Misto Treska, judge

- Mihal Turtulli, politician

- Kristi Vangjeli, football player

- Dhimitër Zografi, signatory of Albanian Declaration of Independence

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Korçë is twinned with:

Ioannina, Greece[49]

Ioannina, Greece[49] Thessaloniki, Greece[50]

Thessaloniki, Greece[50] Cluj-Napoca, Romania[51]

Cluj-Napoca, Romania[51] Mitrovica, Kosovo

Mitrovica, Kosovo Verona, Italy[51]

Verona, Italy[51] Los Alcázares, Spain[51]

Los Alcázares, Spain[51] Shepparton, Australia

Shepparton, Australia

See also

- Autonomous Albanian Republic of Korçë

- Tourism in Albania

- Albanian diaspora

- Music of Albania

- List of castles in Albania

Further reading

- Blocal, Giulia (29 September 2014). "Korça and the hinterlands of South-Eastern Albania". Blocal Travel blog.

- Municipality of Korçë

- N.G.L Hammond, Alexander's Campaign in Illyria, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, pp 4–25. 1974

- James Pettifer, Albania & Kosovo, A & C Black, London (2001, ISBN 0-7136-5016-8)

- François Pouqueville, Voyage en Morée, à Constantinople, an Albanie, et dans plusieurs autres parties de l'Empire othoman, pendant les années 1798, 1799, 1800 et 1801. (1805)

- T.J. Winnifrith Badlands-Borderlands A History of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania (2003)

References

- ↑ Law nr. 115/2014

- ↑ Interactive map administrative territorial reform

- ↑ 2011 census results

- ↑ Carol Zerner, Peter Zerner, John Winder, John Winder. Wace and Blegen: pottery as evidence for trade in the Aegean Bronze age, 1939–1989. J.C. Gieben, 1993, ISBN 978-90-5063-089-4, p. 222

- ↑ Hammond Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière. Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas. Noyes Press, 1976, p. 153.

- ↑ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, page 47, "According to one reconstruction (Hammond) we have the evidence of an Illyrian dynasty being replaced by a Chaonian regime from Northern Epirus"

- ↑ The Cambridge ancient history: The expansion of the ..., Tome 3, Part 3, bt John Boardman,Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond, page 263, "In the plain of Korçë Illyrian rule ended c. 650 BC, when the burials of "

- ↑ The Cambridge ancient history, Tome 3, Part 3, by John Bagnell Bury, "In the plain of Korçë Illyrian rule ended c. 650 BC, when the burials of their chieftains in Tumulus I at Kuci Zi came to an end"

- ↑ John Boardman. The Cambridge Ancient History: pt. 1. The prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. Cambridge University Press, p. 266: "We may conclude, then, that the archaeological division corresponded to a tribal division : the Illyrian tribes holding northern Illyris, and the Epirotic tribes, whether Chaonian or Molossian, holding the plain of Korçë"

- ↑ Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: history and culture. Noyes Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-8155-5052-5. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ Taylor, Stephen (1932). Handbook of Central and East Europe: 1932–33. Zürich: Central European Times Publishing Company. p. 21.

"It was an unimportant little village, named Episkopi until in 1487, when the Albanian Kodja Mirahor Ilias Bey became its administrator and founded the mosque called after him

- ↑ "Korçë". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Masud, Muhammad (2006). Dispensing justice in Islam: Qadis and their judgements. BRILL. p. 283. ISBN 90-04-14067-0.

- ↑ Princeton University. Dept. of Near Eastern Studies. Princeton papers: interdisciplinary journal of Middle Eastern studies. Markus Wiener Publishers, 2002. ISSN 1084-5666, p. 100.

- ↑ Fleming Katherine Elizabeth. The Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4, p. 36: "...Moschopolis, destroyed by resentful Muslim Albanians in 1788"

- ↑ "History of Albania, 1878–1912". World History at KMLA. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ Blumi, Isa (2001). "Teaching Loyalty in the Late Ottoman Balkans: Educational Reform in the Vilayets of Manastir and Yanya, 1878–1912". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 21 (1–2): 19. doi:10.1215/1089201x-21-1-2-15.

- ↑ Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania and King Zog: independence, republic and monarchy 1908–1939. Albania in the twentieth century. 1. I. B. Tauris. p. 35. ISBN 1-84511-013-7.

- ↑ Roudometof, Victor (2002). Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian question. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 155. ISBN 0-275-97648-3.

- 1 2 Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania and King Zog: independence, republic and monarchy 1908–1939. I.B.Tauris. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-84511-013-0. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ↑ Kondis Basil. Greece and Albania, 1908–1914. Institute for Balkan Studies, 1976, p. 130: "The Dutch, having proof that Metropolitan Germanos was chuef instigator of the rising, arrested him and other members of the town council and sent them to Elbasan."

- ↑ Valeria Heuberger; Arnold Suppan; Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus (in German). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-486-56182-1.

- ↑ The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927. William Miller, 1966. ISBN 0-7146-1974-4

- ↑ Kondis Basil. The Greeks of Northern Epirus and Greek-Albanian relations. Hestia, 1995, p. 32: ""a rebellion broke out in Korytsa... their loyalty to the National Defence movement."

- ↑ Schmidt-Neke, Michael (1987). Enstehung und Ausbau der Königsdiktatur in Albanien, 1912–1939. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-486-54321-6. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ↑ Jr, Samuel W. Mitcham, (2007). Eagles of the Third Reich men of the Luftwaffe in World War II. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 114. ISBN 9780811744515.

On the 22d they routed the Italian ninth Army at Koritsa (Korçë) and overran their principal forward air base

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Korçë, Albania". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on November 24, 2011.

- ↑ John Paxton (1 January 2000). The Penguin encyclopedia of places. Penguin. p. 489. ISBN 978-0-14-051275-5.

Cap. of the Korce region and district in the SE. Pop. (1991) 67,100. Market town in a cereal-growing area. Industries inc. knitwear, flour-milling, brewing and sugar-refining. It was an important Orthodox and Muslim religious centre. The fifth .

- ↑ Christopoulos], [publ.: George A. (2000). The splendour of Orthodoxy. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. p. 492. ISBN 9789602133989.

Even before the town itself was built, in 1490, the district of Korytsa belonged the metropolis of Kastoria, which had itself subordinate to the archbishopric of Ohrid. The metropolis of Korytsa was established early in the seventeenth century, incorporating the sees of Kolonia, Debolis, and Selasphoro (Sevdas). The first well- known bishop of Korytsa (1624 and 1628) was Neophytos. In the year 1670 Parthenios, archbishop of Ohrid, a native of Korytsa, elevated his mother town to a metropolitan seat, its occupant bearing the title of bishop of Korytsa, Selapsphoro and Moshopolis

- 1 2 Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2010). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa (1 ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Lang. pp. 37, 79. ISBN 9783631602959.

- ↑ Leustean, Lucian; Leustean, Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations Lucian. Eastern Christianity and the Cold War, 1945-91. Routledge. p. 151. ISBN 9781135233822.

Some landmark churches such as the Saint George Orthodox Cathedral in Korce were raized.1

- ↑ "Iljaz Bej Mirahori". Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- ↑ Petersen, Andrew (1994). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 0-415-06084-2. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- ↑ History of the A. Z. Çajupi Theatre (Korçë municipality website)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Καγιά, Έβις (2006). Το Ζήτημα της Εκπαίδευσης στην Ελληνική Μειονότητα και οι Δίγλωσσοι Μετανάστες Μαθητές στα Ελληνικά Ιδιωτκά Σχολεία στην Αλβανία (in Greek). University of Thessaloniki. pp. 118–121. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ↑ Basil Kondis. The Greeks of Northern Epirus and Greek-Albanian relations. Hestia, 1995, p. 9: ""The first school of the Hellenic type in Korytsa opened in 1724"

- ↑ Sakellariou M. V., Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotikē Athēnōn, 1997, ISBN 978-960-213-371-2, p. 308

- ↑ Basil Kondis. The Greeks of Northern Epirus and Greek-Albanian relations. Hestia, 1995, p. 9 "With the money bequeathed by An. Avramidis two schools of the Hellenic type, a girls' school, and three primary schools were founded"

- ↑ Ismyrliadou, Adela; Karathanasis, Athanasios (1999). "Koritsa: Education-Benefactors-Economy 1850–1908". Balkan Studies. 1 (40): 224–228.

Among them benefactors Ioanis Bangas (1814–1895) and Anastasios Avramidis Liaktsis have a definite place...", "General Rules for Public Institutions in the town of Koritsa were drawn up and changed for the better the functioning of the educational estamblishments.

- ↑ Ismyrliadou, Adela (1996). "Educational and Economic Activities in the Greek Community of Koritsa during the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century". Balkan Studies. 1 (37): 235–255.

- ↑ Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. p. 255. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- ↑ The question of educating Albanians in their mother tongue was raised frequently in the reports of American religious missionaries in the Balkans. In June 1896 Reverend Lewis Bond reported that lessons at the Korça (Korcë) school were conducted in modern Greek, while the local people loved their own tongue, only spoken at home. "Can we do anything for them", asked Reverend Bond. His question obviously remained rhetorical, because three years later he sent another, much more extensive, statement on the issues of the language and education of the Albanians in Korçë. He wrote that only at the girls' school, set up by the Protestant community, the training was in Albanian and once more claimed there was no American who would not sympathise with the Albanians and their desire to use their own language Source : Antonina Zhelyazkova Albanian identities. International centre for minority study and intercultural relations. Sofia. Bulgaria 1999

- 1 2 Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening, 1878–1912. Princeton University Press. p. 134.

- ↑ Clayer, Natalie (2007). Aux origines du nationalisme albanais: la naissance d'une nation majoritairement musulmane en Europe (in French). KARTHALA Editions. pp. 301–10. ISBN 2-84586-816-2.

- ↑ Özdalga, Elisabeth (2005). SOAS/Routledge Curzon studies on the Middle East. 3. Routledge. pp. 264–265. ISBN 0-415-34164-7.

- ↑ Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1924). Southern Albania, 1912–1923. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9780804761710.

several months later, Greek schools were reopened as a result of Greek influence

- ↑ "Albanische Hefte. Parlamentswahlen 2005 in Albanien" (PDF) (in German). Deutsch-Albanischen Freundschaftsgesellschaft e.V. 2005. p. 32.

- ↑ Hermine De Soto (2002). Poverty in Albania : a qualitative assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 32. ISBN 9780821351093.

- ↑ "Twinning Cities". City of Ioannina. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ "Twinning Cities". City of Thessaloniki. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- 1 2 3 Korçë Municipality. "Twin cities" (in Albanian). Korçë Municipality. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Korçë. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Korçë. |