Klondike Gold Rush

Coordinates: 64°3′25″N 139°26′10″W / 64.05694°N 139.43611°W

| Klondike Gold Rush | |

|---|---|

|

Prospectors ascending the Chilkoot Pass, 1898 | |

| Other names | Alaska Gold Rush, Yukon Gold Rush |

| Centre | Dawson City at Klondike River, Yukon Canada |

| Duration | 1896–99 (stampede: 1897–98) |

| Discovery | August 16, 1896, Bonanza Creek |

| Discoverers | George Carmack and Skookum Jim |

| Prospectors | 100,000 of whom 30,000 arrived |

| Routes | Dyea/Skagway route and others |

| Legacy | The Call of the Wild, The Gold Rush |

The Klondike Gold Rush[n 1] was a migration by an estimated 100,000 prospectors to the Klondike region of the Yukon in north-western Canada between 1896 and 1899. Gold was discovered there by local miners on August 16, 1896 and, when news reached Seattle and San Francisco the following year, it triggered a stampede of would-be prospectors. Some became wealthy, but the majority went in vain. It has been immortalized in photographs, books, films, and artifacts.

To reach the gold fields most took the route through the ports of Dyea and Skagway in Southeast Alaska. Here, the Klondikers could follow either the Chilkoot or the White Pass trails to the Yukon River and sail down to the Klondike. Each of them was required to bring a year's supply of food by the Canadian authorities in order to prevent starvation. In all, their equipment weighed close to a ton, which for most had to be carried in stages by themselves. Together with mountainous terrain and cold climate this meant that those who persisted did not arrive until summer 1898. Once there, they found few opportunities and many left disappointed.

Mining was challenging as the ore was distributed in an uneven manner and digging was made slow by permafrost. As a result, some miners chose to buy and sell claims, building up huge investments and letting others do the work. To accommodate the prospectors, boom towns sprang up along the routes and at their end Dawson City was founded at the confluence of the Klondike and the Yukon River. From a population of 500 in 1896, the hastily constructed town came to house around 30,000 people by summer 1898. Built of wood, isolated and unsanitary, Dawson suffered from fires, high prices, and epidemics. Despite this, the wealthiest prospectors spent extravagantly gambling and drinking in the saloons. The Native Hän people, on the other hand, suffered from the rush, being moved into a reserve to make way for the stampeders, and many died.

From 1898, the newspapers that had encouraged so many to travel to the Klondike lost interest in it. In the summer of 1899, gold was discovered around Nome in west Alaska, and many prospectors left the Klondike for the new goldfields, marking the end of the rush. The boom towns declined and the population of Dawson City fell. Gold mining activity lasted until 1903 when production peaked after heavier equipment was brought in. Since then the Klondike has been mined on and off, and today the legacy draws tourists to the region and contributes to its prosperity.[n 2]

Background

The indigenous peoples in north-west America had traded in copper nuggets prior to European expansion. Most of the tribes were aware that gold existed in region but the metal was not valued by them.[2][3][4] The Russians and the Hudson's Bay Company had both explored the Yukon in the first half of the 19th century, but ignored the rumours of gold in favour of fur trading, which offered more immediate profits.[2][n 3]

In the second half of the 19th century, American prospectors began to spread into the area.[6] Making deals with the Native Tlingit and Tagish tribes, the early prospectors opened the important routes of Chilkoot and White Pass, and reached the Yukon valley between 1870 and 1890.[7] Here, they encountered the Hän people, semi-nomadic hunters and fishermen who lived along the Yukon and Klondike Rivers.[8] The Hän did not appear to know about the extent of the gold deposits in the region.[n 4]

In 1883, Ed Schieffelin identified gold deposits along the Yukon River, and an expedition up the Fortymile River in 1886 discovered considerable amounts of it and founded Fortymile City.[9][10] The same year gold had been found on the banks of the Klondike River, but in small amounts and no claims were made.[5] By the late 1880s, several hundred miners were working their way along the Yukon valley, living in small mining camps and trading with the Hän.[11][12][13] On the Alaskan side of the border Circle City, a logtown, was established 1893 on the Yukon River. In three years it grew to become "the Paris of Alaska", with 1,200 inhabitants, saloons, opera houses, schools, and libraries. In 1896, it was so well known that a correspondent from the Chicago Daily Record came to visit. At the end of the year, it became a ghost town, when large gold deposits were found upstream on the Klondike.[14]

Discovery (1896)

On August 16, 1896, an American prospector named George Carmack, his Tagish wife Kate Carmack (Shaaw Tláa), her brother Skookum Jim (Keish), and their nephew Dawson Charlie (K̲áa Goox̱) were travelling south of the Klondike River.[15] Following a suggestion from Robert Henderson, another prospector, they began looking for gold on Bonanza Creek, then called Rabbit Creek, one of the Klondike's tributaries.[16] It is not clear who discovered the gold: George Carmack or Skookum Jim, but the group agreed to let George Carmack appear as the official discoverer because they feared that mining authorities would be reluctant to recognize a claim made by a Native American.[17][18][n 5]

In any event, gold was present along the river in huge quantities.[20] Carmack measured out four claims, strips of ground that could later be legally mined by the owner, along the river; these including two for himself—one as his normal claim, the second as a reward for having discovered the gold—and one each for Jim and Charlie.[21] The claims were registered next day at the police post at the mouth of the Fortymile River and news spread rapidly from there to other mining camps in the Yukon River valley.[22]

By the end of August, all of Bonanza Creek had been claimed by miners.[23] A prospector then advanced up into one of the creeks feeding into Bonanza, later to be named Eldorado Creek. He discovered new sources of gold there, which would prove to be even richer than those on Bonanza.[24] Claims began to be sold between miners and speculators for considerable sums.[25] Just before Christmas, word of the gold reached Circle City. Despite the winter, many prospectors immediately left for the Yukon by dog-sled, eager to reach the region before the best claims were taken.[26] The outside world was still largely unaware of the news and although Canadian officials had managed to send a message to their superiors in Ottawa about the finds and influx of prospectors, the government did not give it much attention.[27] The winter prevented river traffic, and it was not until June 1897 that the first boats left the area, carrying the freshly mined gold and the full story of the discoveries.[28]

Beginning of the stampede (July 1897)

In the Klondike stampede, an estimated 100,000 people tried to reach the Klondike goldfields, of whom only around 30,000 to 40,000 eventually did.[29][n 6] It formed the height of the Klondike gold rush from the summer of 1897 until the summer of 1898. It began on July 15, 1897 in San Francisco and was spurred further two days later in Seattle, when the first of the early prospectors returned from the Klondike, bringing with them large amounts of gold on the ships Excelsior and Portland.[34] The press reported that a total of $1,139,000 (equivalent to $1,000 million at 2010 prices) had been brought in by these ships, although this proved to be an underestimate.[35][n 7] The migration of prospectors caught so much attention that it was joined by outfitters, writers and photographers.[37]

Various factors lay behind this sudden mass response. Economically, the news had reached the US at the height of a series of financial recessions and bank failures in the 1890s. The gold standard of the time tied paper money to the production of gold and shortages towards the end of the 19th century meant that gold dollars were rapidly increasing in value ahead of paper currencies and being hoarded.[38] This had contributed to the Panic of 1893 and Panic of 1896, which caused unemployment and financial uncertainty.[39] There was a huge, unresolved demand for gold across the developed world that the Klondike promised to fulfil and, for individuals, the region promised higher wages or financial security.[38][39]

Psychologically, the Klondike, as historian Pierre Berton describes, was "just far enough away to be romantic and just close enough to be accessible." Furthermore, the Pacific ports closest to the gold strikes were desperate to encourage trade and travel to the region.[40] The mass journalism of the period promoted the event and the human interest stories that lay behind it. A worldwide publicity campaign engineered largely by Erastus Brainerd, a Seattle newspaper man, helped establish the city as the premier supply centre and the departure point for the gold fields.[41][42]

The prospectors came from many nations, although an estimated majority of 60 to 80 percent were Americans or recent immigrants to America.[43][44][n 8] Most had no experience in the mining industry, being clerks or salesmen.[46] Mass resignations of staff to join the gold rush became notorious.[47] In Seattle, this included the mayor, twelve policemen, and a significant percentage of the city's streetcar drivers.[48]

Some stampeders were famous: John McGraw, the former governor of Washington joined, together with the prominent lawyer and sportsman A. Balliot. Frederick Burnham, a well-known American scout and explorer, arrived from Africa, only to be called back to take part in the Second Boer War.[49][50] Among those who documented the rush were the Swedish-born photographer Eric Hegg, who took some of the iconic pictures of Chilkoot Pass, and reporter Tappan Adney, who afterwards wrote a first-hand history of the stampede.[51][n 9] Jack London, later a famous American writer, left to seek for gold but made his money during the rush mostly by working for prospectors.[53][n 10]

Seattle and San Francisco competed fiercely for business during the rush, with Seattle winning the larger share of trade.[54] Indeed, one of the first to join the gold rush was William D. Wood, the mayor of Seattle, who resigned and formed a company to transport prospectors to the Klondike.[41] The publicity around the gold rush led to a flurry of branded goods being put onto the market. Clothing, equipment, food, and medicines were all sold as "Klondike" goods, allegedly designed for the north-west.[55][n 11] Guidebooks were published, giving advice about routes, equipment, mining, and capital necessary for the enterprise.[58][59] The newspapers of the time termed this phenomenon "Klondicitis".[55]

-

_(cropped).jpg)

Klondikers buying miner's licenses at the Custom House in Victoria, BC, on February 12, 1898

-

The S/S Excelsior leaves San Francisco on July 28, 1897, for the Klondike.[n 1]

-

SS Islander leaving Vancouver, bound for Skagway, 1897

- ^ Berton 2001, pp. chp. 4.6 & chp. 7.2.

Cite error: There are <ref group=n> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=n}} template (see the help page).

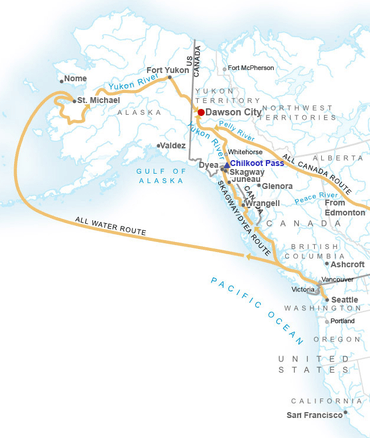

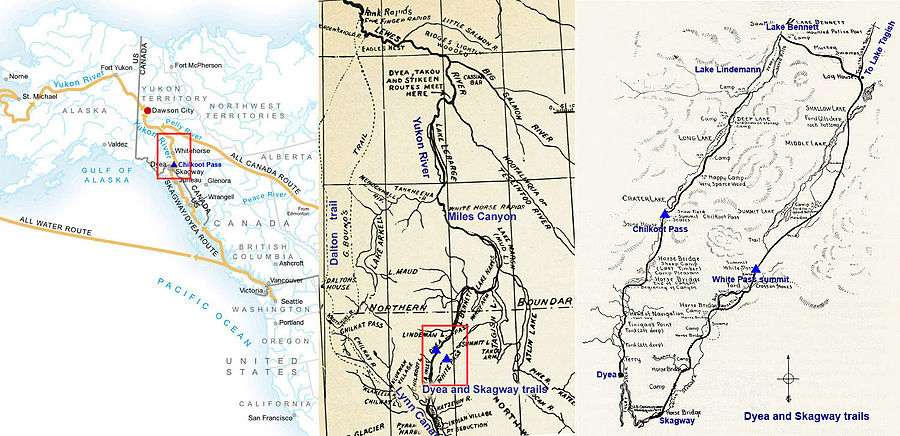

Routes to the Klondike

The Klondike could only be reached by the Yukon River either upstream from its delta, downstream from its head or from somewhere in the middle through its tributaries. River boats could navigate the Yukon in the summer from the delta until a point called Whitehorse, above the Klondike. Travel in general was made difficult by both the geography and climate. The region was mountainous, the rivers winding and sometimes impassable; the short summers could be hot, while from October to June, during the long winters, temperatures could drop below −50 °C (−58 °F).[60][61][n 12]

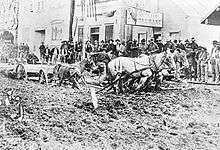

Aids for the travellers to carry their supplies varied; some had brought dogs, horses, mules, or oxen, whereas others had to rely on carrying their equipment on their backs or on sleds pulled by hand.[64] Shortly after the stampede began in 1897, the Canadian authorities had introduced rules requiring anyone entering Yukon Territory to bring with them a year's supply of food; typically this weighed around 1,150 pounds (520 kg).[65] By the time camping equipment, tools and other essentials were included, a typical traveller was transporting as much as a ton in weight.[65] Unsurprisingly, the price of draft animals spiralled; at Dyea, even poor quality horses could sell for as much as $700 ($19,000), or be rented out for $40 ($1,100) a day.[66][n 13]

From Seattle or San Francisco, prospectors could travel by sea up the coast to the ports of Alaska.[68] The route following the coast is now referred to as the Inside Passage. It led to the ports of Dyea and Skagway plus ports of nearby trails. The sudden increase in demand encouraged a range of vessels to be pressed into service including old paddle wheelers, fishing boats, barges, and coal ships still full of coal dust. All were overloaded and many sank.[69]

All water route

It was possible to sail all the way to the Klondike, first from Seattle across the northern Pacific to the Alaskan coast. From St. Michael, at the Yukon River delta, a river boat could then take the prospectors the rest of the way up the river to Dawson, often guided by one of the Native Koyukon people who lived near St. Michael.[70][71] Although this all-water route, also called "the rich man's route", was expensive and long, 4,700 miles (7,600 km) in total, it had the attraction of speed and avoiding overland travel.[70] At the beginning of the stampede a ticket could be bought for $150 ($4,050) while during the winter 1897–98 the fare settled at $1,000 ($27,000).[72][n 14]

In 1897, 1,800 travellers attempted this route but the vast majority were caught along the river when the region iced over in October.[70] Only 43 successfully reached the Klondike before winter and of those 35 had to return, having thrown away their equipment en route to reach their destination in time.[70] The remainder mostly found themselves stranded in isolated camps and settlements along the ice-covered river often in desperate circumstances.[74][n 15]

Dyea/Skagway routes

Most of the prospectors landed at the southeast Alaskan towns of Dyea and Skagway, both located at the head of the natural Lynn Canal at the end of the Inside Passage. From there, they needed to travel 30 miles (48 km) over the mountain ranges into Canada's Yukon Territory, and then down the river network to the Klondike.[76] Along the trails, tent camps sprung up at places where prospectors had to stop to eat or sleep or at obstacles such as the icy lakes at the head of the Yukon.[77][78] At the start of the rush, a ticket from Seattle to the port of Dyea cost $40 ($1,100) for a cabin. Premiums of $100 ($2,700), however, were soon paid and the steamship companies hesitated to post their rates in advance since they could increase on a daily basis.[79]

White Pass trail

Those who landed at Skagway made their way over the White Pass before cutting across to Bennett Lake.[80] Although the trail began gently, it progressed over several mountains with paths as narrow as 2 feet (0.61 m) and in wider parts covered with boulders and sharp rocks.[81] Under these conditions horses died in huge numbers, giving the route the informal name of Dead Horse Trail.[76][n 16] The volumes of travellers and the wet weather made the trail impassable and, by late 1897, it was closed until further notice, leaving around 5,000 stranded in Skagway.[81]

An alternative toll road suitable for wagons was eventually constructed and this, combined with colder weather that froze the muddy ground, allowed the White Pass to reopen, and prospectors began to make their way into Canada.[81] Moving supplies and equipment over the pass had to be done in stages. Most divided their belongings into 65 pounds (29 kg) packages that could be carried on a man's back, or heavier loads that could be pulled by hand on a sled.[64] Ferrying packages forwards and walking back for more, a prospector would need about thirty round trips, a distance of at least 2,500 miles (4,000 km), before they had moved all of their supplies to the end of the trail. Even using a heavy sled, a strong man would be covering 1,000 miles (1,600 km) and need around 90 days to reach Lake Bennett.[83][n 17]

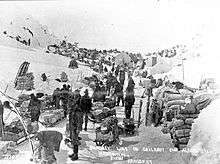

Chilkoot trail

Those who landed at Dyea, Skagway's neighbour town, travelled the Chilkoot Trail and crossed its pass to reach Lake Lindeman, which fed into Lake Bennett at the head of the Yukon River.[85] The Chilkoot Pass was higher than the White Pass, but more used it: around 22,000 during the gold rush.[86] The trail passed up through camps until it reached a flat ledge, just before the main ascent, which was too steep for animals.[87][n 19] This location was known as the Scales, and was where goods were weighed before travellers officially entered Canada. The cold, the steepness and the weight of equipment made the climb extremely arduous and it could take a day to get to the top of the 1,000 feet (300 m) high slope.[89]

As on the White Pass trail, supplies needed to be broken down into smaller packages and carried in relay.[90] Packers, prepared to carry supplies for cash, were available along the route but would charge up to $1 ($27) per lb (0.45 kg) on the later stages; many of these packers were natives: Tlingits or, less commonly, Tagish.[87][91][92] Avalanches were common in the mountains and, on April 3, 1898, one claimed the lives of more than 60 people travelling over Chilkoot Pass.[93][n 20]

Entrepreneurs began to provide solutions as the winter progressed. Steps were cut into the ice at the Chilkoot Pass which could be used for a daily fee, this 1,500 step staircase becoming known as the "Golden Steps".[95] By December 1897, Archie Burns built a tramway up the final parts of the Chilkoot Pass. A horse at the bottom turned a wheel, which pulled a rope running to the top and back; freight was loaded on sledges pulled by the rope. Five more tramways soon followed, one powered by a steam engine, charging between 8 and 30 cents ($2 and $8) per 1 pound (0.45 kg).[96] An aerial tramway was built in the spring of 1898, able to move 9 tonnes of goods an hour up to the summit.[96][62]

Head of Yukon River

At Lakes Bennett and Lindeman, the prospectors camped to build rafts or boats that would take them the final 500 miles (800 km) down the Yukon to Dawson City in the spring.[97][n 21] 7,124 boats of varying size and quality left in May 1898; by that time, the forests around the lakes had been largely cut down for timber.[99][100] The river posed a new problem. Above Whitehorse, it was dangerous, with several rapids along the Miles Canyon through to the White Horse Rapids.[101]

After many boats were wrecked and several hundred people died, the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) introduced safety rules, vetting the boats carefully and forbidding women and children to travel through the rapids.[102][53][n 22] Additional rules stated that any boat carrying passengers required a licensed pilot, typically costing $25 ($680), although some prospectors simply unpacked their boats, let them drift unmanned through the rapids with the intent of walking down to collect them on the other side.[53] During the summer, a horse-powered rail-tramway was built by Norman Macaulay, capable of carrying boats and equipment through the canyon at $25 ($680) a time, removing the need for prospectors to navigate the rapids.[103]

-

Prospectors in a tent camp at Bennett Lake waiting for the ice on Yukon River to break up, May 1898

-

Klondikers sailing toward Dawson on the upper Yukon River, 1898.

Parallel trails

There were a few more trails established during 1898 from South-east Alaska to the Yukon River. One was the Dalton trail: starting from Pyramid Harbour, close to Dyea, it went across the Chilkat Pass some miles west of Chilkoot and turned north to the Yukon River, a distance of about 350 miles (560 km). This was created by Jack Dalton as a summer route, intended for cattle and horses, and Dalton charged a toll of $250 ($6,800) for its use.[104]

The Takou route started from Juneau and went north-east to Teslin Lake. From here, it followed a river to the Yukon, where it met the Dyea and Skagway route at a point halfway to the Klondike.[105] It meant dragging and poling canoes up-river and through mud together with crossing a 5,000 feet (1,500 m) mountain along a narrow trail. Finally, there was the Stikine route starting from the port of Wrangell further south-east of Skagway. This route went up the uneasy Stikine River to Glenora, the head of navigation. From Glenora, prospectors would have to carry their supplies 150 miles (240 km) to Teslin Lake where it, like the Takou route, met the Yukon River system.[106]

All-Canadian routes

An alternative to the South-east Alaskan ports were the All-Canadian routes, so-called because they mostly stayed on Canadian soil throughout their journey.[107] These were popular with British and Canadians for patriotic reasons and because they avoided American customs.[107] The first of these, around 1,000 miles (1,600 km) in length, started from Ashcroft in British Columbia and crossed swamps, river gorges, and mountains until it met with the Stikine River route at Glenora.[106][n 23] From Glenora, prospectors would face the same difficulties as those who came from Wrangell.[106] At least 1,500 men attempted to travel along the Ashcroft route and 5,000 along the Stikine.[109] The mud and the slushy ice of the two routes proved exhausting, killing or incapacitating the pack animals and creating chaos amongst the travellers.[110]

Three more routes started from Edmonton, Alberta; these were not much better - barely trails at all - despite being advertised as "the inside track" and the "back door to the Klondike".[111][112] One, the "overland route", headed north-west from Edmonton, ultimately meeting the Peace River and then continuing on overland to the Klondike, crossing the Liard River en route.[113] To encourage travel via Edmonton, the government hired T.W. Chalmers to build a trail, which became known as the Klondike Trail or Chalmers Trail.[114] The other two trails, known as the "water routes", involved more river travel. One went by boat along rivers and overland to the Yukon River system at Pelly River and from there to Dawson.[115] Another went north of Dawson by the Mackenzie River to Fort McPherson, before entering Alaska and meeting the Yukon River at Fort Yukon, downstream to the Klondike.[115][116] From here, the boat and equipment had to be pulled up the Yukon about 400 miles (640 km). An estimated 1,660 travellers took these three routes, of whom only 685 arrived, some taking up to 18 months to make the journey.[117]

"All-American" route

An equivalent to the All-Canadian routes was the "All-American route", which aimed to reach the Yukon from the port of Valdez, which lay further along the Alaskan coast from Skagway.[118] This, it was hoped, would evade the Canadian customs posts and provide an American-controlled route into the interior.[119] 3,500 men and women attempted it from late 1897 onwards; delayed by the winter snows, fresh efforts were made in the spring.[120]

In practice, the huge Valdez glacier that stood between the port and the Alaskan interior proved almost insurmountable and only 200 managed to climb it; by 1899, the cold and scurvy was causing many deaths amongst the rest.[121] Other prospectors attempted an alternative route across the Malaspina Glacier just to the east, suffering even greater hardships.[122] Those who did manage to cross it found themselves having to negotiate miles of wilderness before they could reach Dawson. Their expedition was forced to turn back the same way they had come with only four men surviving.[123]

Border control

The borders in South-east Alaska were disputed between the US, Canada and Britain since the American purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867.[125] The US and Canada both claimed the ports of Dyea and Skagway.[125] This, combined with the numbers of American prospectors, the quantities of gold being mined and the difficulties in exercising government authority in such a remote area, made the control of the borders a sensitive issue.[126]

Early on in the gold rush, the US Army sent a small detachment to Circle City, in case intervention was required in the Klondike, while the Canadian government considered excluding all American prospectors from the Yukon Territory.[127] Neither eventuality took place and instead the US agreed to make Dyea a sub-port of entry for Canadians, allowing British ships to land Canadian passengers and goods freely there, while Canada agreed to permit American miners to operate in the Klondike.[128] Both decisions were unpopular among their domestic publics: American businessmen complained that their right to a monopoly on regional trade was being undermined, while the Canadian public demanded action against the American miners.[128]

The North-West Mounted Police set up control posts at the borders of the Yukon Territory or, where that was disputed, at easily controlled points such as the Chilkoot and White Passes.[129] These units were armed with Maxim guns.[130] Their tasks included enforcing the rules requiring that travellers bring a year's supply of food with them to be allowed into the Yukon Territory, checking for illegal weapons, preventing the entry of criminals and enforcing customs duties.[131]

This last task was particularly unpopular with American prospectors, who faced paying an average of 25 percent of the value of their goods and supplies.[132] The Mounties had a reputation for running these posts honestly, although accusations were made that they took bribes.[133] Prospectors, on the other hand, tried to smuggle prize items like silk and whiskey across the pass in tins and bales of hay: the former item for the ladies, the latter for the saloons.[134]

Mining

Of the estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people who reached Dawson City during the gold rush, only around 15,000 to 20,000 finally became prospectors. Of these, no more than 4,000 struck gold and only a few hundred became rich.[29] By the time most of the stampeders arrived in 1898, the best creeks had all been claimed, either by the long-term miners in the region, or by the first arrivals of the year before.[135] The Bonanza, Eldorado, Hunker and Dominion Creeks were all taken, with almost 10,000 claims recorded by the authorities by July 1898; a new prospector would have to look further afield to find a claim of his own.[136]

Geologically, the region was permeated with veins of gold, forced to the surface by volcanic action and then worn away by the action of rivers and streams, leaving nuggets and gold dust in deposits known as placer gold.[137][n 25] Some ores lay along the creek beds in lines of soil, typically 15 feet (4.6 m) to 30 feet (9.1 m) beneath the surface.[138] Others, formed by even older streams, lay along the hilltops; these deposits were called "bench gold".[139] Finding the gold was challenging. Initially, miners had assumed that all the gold would be along the existing creeks, and it was not until late in 1897 that the hilltops began to be mined.[140] Gold was also unevenly distributed in the areas where it was found, which made prediction of good mining sites even more uncertain.[141] The only way to be certain that gold was present was to conduct exploratory digging.[142]

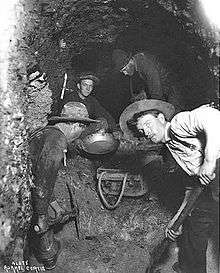

Methods

Mining began with clearing the ground of vegetation and debris.[143] Prospect holes were then dug in an attempt to find the ore or "pay streak".[143] If these holes looked productive, proper digging could commence, aiming down to the bedrock, where the majority of the gold was found.[143] The digging would be carefully monitored in case the operation needed to be shifted to allow for changes in the flow.[143]

In the sub-Arctic climate of the Klondike, a layer of hard permafrost lay only 6 feet (1.8 m) below the surface.[144][145] Traditionally, this had meant that mining in the region only occurred during the summer months, but the pressure of the gold rush made such a delay unacceptable.[142] Late 19th century technology existed for dealing with this problem, including hydraulic mining and stripping, and dredging, but the heavy equipment required for this could not be brought into the Klondike during the gold rush.[144][146]

Instead, the miners relied on wood fires to soften the ground to a depth of about 14 inches (360 mm) and then removing the resulting gravel. The process was repeated until the gold was reached. In theory, no support of the shaft was necessary because of the permafrost although in practice sometimes the fire melted the permafrost and caused collapses.[147] Fires could also produce noxious gases, which had to be removed by bellows or other tools.[148][149] The resulting "dirt" brought out of the mines froze quickly in winter and could only be processed during the warmer summer months.[149][n 26] An alternative, more efficient, approach called steam thawing was devised between 1897 and 1898; this used a furnace to pump steam directly into the ground, but since it required additional equipment it was not a widespread technique during the years of the rush.[150]

In the summer, water would be used to sluice and pan the dirt, separating out the heavier gold from gravel.[151] This required miners to construct sluices, which were sequences of wooden boxes 15 feet (4.6 m) long, through which the dirt would be washed; up to 20 of these might be needed for each mining operation.[152] The sluices in turn required lots of water, usually produced by creating a dam and ditches or crude pipes.[153] "Bench gold" mining on the hill sides could not use sluice lines because water could not be pumped that high up. Instead, these mines used rockers, boxes that moved back and forth like a cradle, to create the motion needed for separation.[154] Finally, the resulting gold dust could be exported out of the Klondike; exchanged for paper money at the rate of $16 ($430) per troy ounce (ozt) through one of the major banks that opened in Dawson City, or simply used as money when dealing with local traders.[155][n 27]

Business

Successful mining took time and capital, particularly once most of the timber around the Klondike had been cut down.[153] A realistic mining operation required $1,500 ($1.2 million) for wood to be burned to melt the ground, along with around $1,000 ($800,000) to construct a dam, $1,500 ($1.2 million) for ditches and up to $600 ($480,000) for sluice boxes, a total of $4,600.[153] The attraction of the Klondike to a prospector, however, was that when gold was found, it was often highly concentrated.[157] Some of the creeks in the Klondike were fifteen times richer in gold than those in California, and richer still than those in South Africa.[157] In just two years, for example, $230,000 ($1,840 million) worth of gold was brought up from claim 29 on the Eldorado Creek.[158][n 28]

Under Canadian law, miners first had to get a license, either when they arrived at Dawson or en route from Victoria in Canada.[160] They could then prospect for gold and, when they had found a suitable location, lay claim to mining rights over it.[161] To stake a claim, a prospector would drive stakes into the ground a measured distance apart and then return to Dawson to register the claim for $15 ($410).[161] This normally had to be done within three days, and by 1897 only one claim per person at a time was allowed in a district, although married couples could exploit a loophole that allowed the wife to register a claim in her own name, doubling their amount of land.[162][163]

The claim could be mined freely for a year, after which a $100 ($2,800) fee had to be paid annually. Should the prospector leave the claim for more than three days without good reason, another miner could make a claim on the land.[164] The Canadian government also charged a royalty of between 10 and 20 percent on the value of gold taken from a claim.[165]

Traditionally, a mining claim had been granted over a 500-foot (150 m) long stretch of a creek, including the land from one side of the valley to another. The Canadian authorities had tried to reduce this length to 150 feet (46 m), but under pressure from miners had been forced to agree to 250 feet (76 m). The only exception to this was a "Discovery" claim, the first to be made on a creek, which could be 500 feet (150 m) long.[166][n 29] The exact lengths of claims were often challenged and when the government surveyor William Ogilvie conducted surveys to settle disputes, he found some claims exceeded the official limit.[168] The excess fractions of land then became available as claims and were sometimes quite valuable.[168]

Claims could be bought. However, their price depended on whether they had been yet proved to contain gold.[169] A prospector with capital might consider taking a risk on an "unproved" claim on one of the better creeks for $5,000 ($4,000,000); a wealthier miner could buy a "proved" mine for $50,000 ($40,000,000).[169] The well known claim eight on Eldorado Creek was sold for as much as $350,000 ($280 million).[169] Prospectors were also allowed to hire others to work for them, either on their first claim or on later purchases.[170] Enterprising miners such as Alex McDonald set about amassing mines and employees.[171] Leveraging his acquisitions with short term loans, by the autumn of 1897 McDonald had purchased 28 claims, estimated to be worth millions.[171] Swiftwater Bill Gates famously borrowed heavily against his claim on the Eldorado creek, relying on hired hands to mine the gold to keep up his interest payments.[172]

The less fortunate or less well funded prospectors rapidly found themselves destitute. Some chose to sell their equipment and return south.[173] Others took jobs as manual workers, either in mines or in Dawson; the typical daily pay of $15 ($410) was high by external standards, but low compared to the cost of living in the Klondike.[173] The possibility that a new creek might suddenly produce gold, however, continued to tempt poorer prospectors.[173] Smaller stampedes around the Klondike continued throughout the gold rush, when rumours of new strikes would cause a small mob to descend on fresh sites, hoping to be able to stake out a high value claim.[174]

Life in the Klondike

The massive influx of prospectors drove the formation of boom towns along the routes of the stampede, with Dawson City in the Klondike the largest.[175][176] The new towns were crowded, often chaotic and many disappeared just as soon as they came.[177] Most stampeders were men but women also travelled to the region, typically as the wife of a prospector.[178] Some women entertained in gambling and dance halls built by business men and women who were encouraged by the lavish spending of successful miners.[179]

Dawson remained relatively lawful, protected by the Canadian NWMP, which meant that gambling and prostitution were accepted while robbery and murder were kept low. By contrast, especially the port of Skagway under US jurisdiction in Southeast Alaska became infamous for its criminal underworld.[180][181] The extreme climate and remoteness of the region in general meant that supplies and communication with the outside world including news and mail were scarce.[176][182]

Boom towns

The ports of Dyea and Skagway, through which most of the prospectors entered, were tiny settlements before the gold rush, each consisting of only one log cabin.[183] Because there were no docking facilities, ships had to unload their cargo directly onto the beach, where people tried to move their goods before high tide.[184] Inevitably cargos were smashed, stolen or lost in the process.[185] Some travellers had arrived intending to supply goods and services to the would-be miners; some of these in turn, realizing how difficult it would be to reach Dawson, chose to do the same.[184] Within weeks, storehouses, saloons, and offices lined the muddy streets of Dyea and Skagway, surrounded by tents and hovels.[175]

Skagway became famous in international media; the author John Muir described the town as "a nest of ants taken into a strange country and stirred up by a stick".[185] While Dyea remained a transit point throughout the winter, Skagway began to take on a more permanent character.[186] Skagway also built wharves out into the bay in order to attract a greater share of the prospectors.[187] The town was effectively lawless, dominated by drinking, gunfire and prostitution.[188] The visiting NWMP Superintendent Sam Steele noted that it was "little better than a hell on earth ... about the roughest place in the world".[189] Nonetheless, by the summer of 1898, with a population—including migrants—of between 15,000 and 20,000, Skagway was the largest city in Alaska.[190]

In late summer 1897 Skagway and Dyea fell under the control of Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith and his men, who arrived from Seattle shortly after Skagway began to expand.[191][192] He was an American confidence man whose gang, 200 to 300 strong, cheated and stole from the prospectors travelling through the region.[193][n 30] He maintained the illusion of being an upstanding member of the community, opening three saloons as well as creating fake businesses to assist in his operations.[195][196] One of his scams was a fake telegraph office charging to send messages all over the US and Canada, often pretending to receive a reply.[197] Opposition to Smith steadily grew and, after weeks of vigilante activity, he was killed in Skagway during the shootout on Juneau Wharf on July 8, 1898.[191][198]

Other towns also boomed. Wrangell, port of the Stikine route and boom town from earlier gold rushes, increased in size again, with robberies, gambling and nude female dancing commonplace.[199] Valdez, formed on the Gulf of Alaska during the attempt to create the "All-American" route to the Klondike during the winter of 1897–1898, became a tent city of people who stayed behind to supply the ill-fated attempts to reach the interior.[121] Edmonton in Canada increased from a population of 1,200 before the gold rush to 4,000 during 1898.[200] Beyond the immediate region, cities such as San Francisco, Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, Vancouver and Victoria all saw their populations soar as a result of the stampede and the trade it brought along.[200]

Dawson City

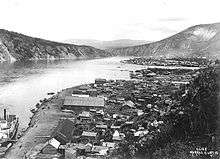

Dawson City was created in the early days of the Klondike gold rush, when prospector Joe Ladue and shopkeeper Arthur Harper decided to make a profit from the influx to the Klondike.[22][201] The two men bought 178 acres (72 ha) of the mudflats at the junction of the Klondike and Yukon rivers from the government and laid out the street plan for a new town, bringing in timber and other supplies to sell to the migrants.[202] The Hän village of Tr'ochëk along Deer Creek was considered to be too close to the new town, and the NWMP Superintendent Charles Constantine moved its inhabitants 3 miles (4.8 km) down-river to a small reserve.[203] The town, in the beginning simply known as "Harper and Ladue town site", was named Dawson City after the director of Canada's Geographical Survey.[176] It grew rapidly to hold 500 people by the winter of 1896, with plots of land selling for $500 ($400,000) each.[176]

In the spring of 1898, Dawson's population rose further to 30,000 as stampeders arrived over the passes.[176] The centre of the town, Front Street, was lined with hastily built buildings and warehouses, together with log cabins and tents spreading out across the rest of the settlement.[204] There was no running water or sewerage, and only two springs for drinking water to supplement the increasingly polluted river.[205] In spring, the unpaved streets were churned into thick mud and in summer the settlement reeked of human effluent and was plagued by flies and mosquitoes.[206] Land in Dawson was now scarce, and plots sold for up to $10,000 ($8 million) each; prime locations on Front Street could reach $20,000 ($16 million) while a small log cabin might rent for $100 ($2,700) a month.[207] As a result, Dawson's population spread south into the empty Hän village, renaming it Klondike City.[208] Other communities emerged closer to the mines, such as Granville on Dominion Creek and Grand Forks on Bonanza Creek.[209][210]

The newly built town proved highly vulnerable to fire. Houses were made of wood, heated with stoves and lit by candles and oil lamps; water for emergencies was wanting, especially in the frozen winters.[211] The first major fire occurred on November 25, 1897, started accidentally by dance-hall girl Belle Mitchell.[212] She also accidentally started a second major fire on October 14, 1898 which, in the absence of a fire brigade in Dawson, destroyed two major saloons, the post-office building and the Bank of British North America at a cost of $500,000 ($400 million).[213][214][n 31] The worst fire occurred on April 26, 1899 when a saloon caught fire in the middle of a strike by the newly established fire brigade.[215] Most of the major landmarks in the town were burned to the ground: 117 buildings were destroyed, with the damage estimated at over $1 million ($810 million).[216][217][n 32]

Logistics

The remoteness of Dawson proved an ongoing problem for the supply of food and as the population grew to 5,000 in 1897 this became critical.[176][182] When the rivers iced over, it became clear that there would not be enough food for that winter.[219] The NWMP evacuated some prospectors without supplies to Fort Yukon in Alaska from September 30 onwards, while others made their way out of the Klondike in search of food and shelter for the winter.[220][n 33]

Prices remained high in Dawson and supply fluctuated according to the season. During the winter of 1897 salt became worth its weight in gold, while nails, vital for construction work, rose in price to $28 ($760) per lb (0.45 kg).[222] Cans of butter sold for $5 ($140) each.[223] The only eight horses in Dawson were slaughtered for dog food as they could not be kept alive over the winter.[222][n 34] The first fresh goods arriving in the spring of 1898 sold for record prices, eggs reaching $3 ($81) each and apples $1 ($27).[226]

Under these conditions scurvy, a potentially fatal illness caused by the lack of vitamin C, proved a major problem in Dawson City, particularly during the winter where supply of fresh food was not available. English prospectors gave it the local name of "Canadian black leg", on account of the unpleasant effects of the condition.[227][228] It struck, among others, writer Jack London and, although not fatal in his case, brought an end to his mining career.[229] Dysentery and malaria were also common in Dawson, and an epidemic of typhoid broke out in July and ran rampant throughout the summer.[230] Up to 140 patients were taken into the newly constructed St Mary's Hospital and thousands were affected.[231] Measures were taken by the following year to prevent further outbreaks, including the introduction of better sewage management and the piping in of water from further upstream.[230] These gave improvements in 1899, although typhoid remained a problem.[230] The new Hän reserve, however, lay downstream from Dawson City, and here the badly contaminated river continued to contribute to epidemics of typhoid and diphtheria throughout the gold rush.[232][n 35]

Conspicuous consumption

Despite these challenges, the huge quantities of gold coming through Dawson City encouraged a lavish lifestyle amongst the richer prospectors. Saloons were typically open 24 hours a day, with whiskey the standard drink.[234] Gambling was popular, with the major saloons each running their own rooms; a culture of high stakes evolved, with rich prospectors routinely betting $1,000 ($27,000) at dice or playing for a $5,000 ($140,000) poker pot.[234][n 36] The establishments around Front Street had grand facades in a Parisian style, mirrors and plate-glass windows and, from late 1898, were lit by electric light.[236] The dance halls in Dawson were particularly prestigious and major status symbols, both for customers and their owners.[237] Wealthy prospectors were expected to drink champagne at $60 ($1,600) a bottle, and the Pavilion dancehall cost its owner, Charlie Kimball, as much as $100,000 ($80 million) to construct and decorate.[238] Elaborate opera houses were built, bringing singers and specialty acts to Dawson.[239]

Tales abounded of prospectors spending huge sums on entertainment — Jimmy McMahon once spent $28,000 ($760,000) in a single evening, for example.[240] Most payments were made in gold dust and in places like saloons, there was so much spilled gold that a profit could be made just by sweeping the floor.[227] Some of the richest prospectors lived flamboyantly in Dawson. Swiftwater Bill Gates, a gambler and ladies man who rarely went anywhere without wearing silk and diamonds, was one of them. To impress a woman who liked eggs—then an expensive luxury—he was alleged to have bought all the eggs in Dawson, had them boiled and fed them to dogs.[241] Another miner, Frank Conrad, threw a sequence of gold objects onto the ship when his favourite singer left Dawson City as tokens of his esteem.[242][243] The wealthiest dance-hall girls followed suit: Daisy D'Avara had a belt made for herself from $340 ($9,200) in gold dollar coins; another, Gertie Lovejoy, had a diamond inserted between her two front teeth.[244] The miner and businessman Alex McDonald, despite being styled the "King of the Klondike", was unusual amongst his peers for his lack of grandiose spending.

Law and order

Unlike its American equivalents, Dawson City was a law-abiding town.[180][181] By 1897, 96 members of the NWMP had been sent to the district and by 1898 this had increased to 288, an expensive commitment by the Canadian government.[245][n 37] By June 1898 the force was headed by Colonel Sam Steele, an officer with a reputation for firm discipline.[246] In 1898, there were no murders and only a few major thefts; in all, only about 150 arrests were made in the Yukon for serious offenses that year.[247] Of these arrests, over half were for prostitution and resulted from an attempt by the NWMP to regulate the sex industry in Dawson: regular monthly arrests, $50 ($1,400) fines and medical inspections were imposed, with the proceeds being used to fund the local hospitals.[247][248] The so-called blue laws were strictly enforced. Saloons and other establishments closed promptly at midnight on Saturday, and anyone caught working on Sunday was liable to be fined or set to chopping firewood for the NWMP.[249][n 38] The NWMP are generally regarded by historians to have been an efficient and honest force during the period, although their task was helped by the geography of the Klondike which made it relatively easy to bar entry to undesirables or prevent suspects from leaving the region.[182][251]

In contrast to the NWMP, the early civil authorities were criticized by the prospectors for being inept and potentially corrupt.[252] Thomas Fawcett was the gold commissioner and temporary head of the Klondike administration at the start of the gold rush; he was accused of keeping the details of new claims secret and allowing what historian Kathryn Winslow termed "carelessness, ignorance and partiality" to reign in the mine recorder's office.[253] Following campaigns against him by prospectors, who were backed by the local press, Fawcett was relieved by the Canadian government.[254] His successor, Major James Walsh, was considered a stronger character and arrived in May 1898 but fell ill and returned east in July.[253] It was left to his replacement, William Ogilvie, supported by a Royal Commission, to conduct reforms.[253] The Commission, in lack of evidence, cleared Fawcett of all charges, which meant that he was not punished further than being relieved.[253] Ogilvie proved a much stronger administrator and subsequently revisited many of the mining surveys of his predecessors.[255]

News and mail

In the remote Klondike, there was a great demand for news and contact with the world outside. During the first months of the stampede in 1897, it was said that no news was too old to be read. In the lack of newspapers, some prospectors would read can labels until they knew them by heart.[256] The following year, two teams fought their way over the passes to reach Dawson City first, complete with printing-presses, with the aim of gaining control of the newspaper market.[257] Gene Kelly, the editor of the Klondike Nugget arrived first, but without his equipment, and it was the team behind the Midnight Sun who produced the first daily newspaper in Dawson.[257][258][259] The Dawson Miner followed shortly after, bringing the number of daily newspapers in the town during the gold rush up to three.[260] The Nugget sold for $24 ($680) as an annual subscription, and became well known for championing popular causes associated with miners and for its lucid coverage of scandals.[261] Paper was often hard to find and during the winter of 1898–99, the Nugget had to be printed on butcher's wrapping paper.[262] In the lack of paper, news could be told. In June, 1898, a prospector bought an edition of the Seattle Post-Intellinger at an auction and charged spectators a dollar each to have it read aloud in one of Dawson's halls.[263]

The mail service was chaotic and ill-organised, not at least because government had not anticipated the stampede of prospectors from the United States to the region.[264] Two major problems stood in the way of an effective system. To begin with, any mail from America to Dawson City was sent to Juneau in South-east Alaska before being sent through Dawson and then down the Yukon to Circle City. From here it was then distributed by the US Post Office back up to Dawson.[265] The huge distances involved resulted in delays of several months and frequently the loss of protective envelopes and their addresses.[265] The second problem was in Dawson itself, which initially lacked a post office and therefore relied on two stores and a saloon to act as informal delivery points.[265] The NWMP were tasked to run the mail system by October 1897, but they were ill-trained to do so.[265] Up to 5,700 letters might arrive in a single shipment, all of which had to be collected in person from the post office. This resulted in huge queues, with claimants lining up outside the office for up to three days.[265] Those who had no time and could afford it would pay others to stand in line for them, preferably a woman since they were allowed to get ahead in line out of politeness.[266] Postage stamps, like paper in general, were scarce and rationed to two per customer.[265] By 1899, trained postal staff took over mail delivery and relieved the NWMP of this task.[267]

Role of women

In 1898 eight percent of those living in the Klondike territory were women, and in towns like Dawson this rose to 12 percent.[178] Many women arrived with their husbands or families, but others travelled alone.[268] Most came to the Klondike for similar economic and social reasons as male prospectors, but they attracted particular media interest.[269] The gender imbalance in the Klondike encouraged business proposals to ship young, single women into the region to marry newly wealthy miners; few, if any, of these marriages ever took place, but some single women appear to have travelled on their own in the hope of finding prosperous husbands.[270] Guidebooks gave recommendations for what practical clothes women should take to the Klondike: the female dress code of the time was formal, emphasising long skirts and corsets, but most women adapted this for the conditions of the trails.[271] Regardless of experience, women in a party were typically expected to cook for the group.[272] Few mothers brought their children with them to the Klondike, due to the risks of the travel and the remote location.[273]

Once in the Klondike, very few women—less than one percent—actually worked as miners.[274] Many were married to miners; however, their lives as partners on the gold fields were still hard and often lonely. They had extensive domestic duties, including thawing ice and snow for water, breaking up frozen food, chopping wood and collecting wild foods.[275] In Dawson and other towns, some women took in laundry to make money.[276] This was a physically demanding job, but could be relatively easily combined with child care duties.[276] Others took jobs in the service industry, for example as waitresses or seamstresses, which could pay well, but were often punctuated by periods of unemployment.[277] Both men and women opened roadhouses, but women were considered to be better at running them.[278] A few women worked in the packing trade, carrying goods on their backs, or became domestic servants.[279]

Wealthier women with capital might invest in mines and other businesses.[280] One of the most prominent businesswomen in the Klondike, was Belinda Mulrooney. She brought a consignment of cloth and hot water bottles with her when she arrived in the Klondike in early 1897 and with the proceeds of those sales she first built a roadhouse at Grand Forks and later a grand hotel in Dawson.[281] She invested widely, including acquiring her own mining company, and was reputed to be the richest woman of the Klondike.[282][283] The wealthy Martha Black was abandoned by her husband early in the journey to the Klondike, but continued on without him, reaching Dawson City where she became a prominent citizen, investing in various mining and business ventures with her brother.[284][285]

A relatively small number of women worked in the entertainment and sex industries.[286] The elite of these women were the highly paid actresses and courtesans of Dawson; beneath them were chorus line dancers, who usually doubled as hostesses, and other dance hall workers.[287] While still better paid than white-collar male workers, these women worked very long hours and had significant expenses.[288] The entertainment industry merged into the sex industry, where women made a living as prostitutes. The sex industry in the Klondike was concentrated on Klondike City and in a backstreet area of Dawson.[289] A hierarchy of sexual employment existed, with brothels and parlour houses at the top, small independent "cigar shops" in the middle, and, at the bottom, the prostitutes who worked out of small huts called "hutches".[290] Life for these workers was a continual struggle and the suicide rate was high.[291][292]

The degree of involvement between Native women and the stampeders varied. Many Tlingit women worked as packers for the prospectors, for example, carrying supplies and equipment, sometimes also transporting their babies as well.[293] Hän women had relatively little contact with the white immigrants, however, and there was a significant social divide between local Hän women and white women.[294] Although before 1897 there had been a number of Native women who married western men, including Kate Carmack, the Tagish wife of one of the discoverers, this practice did not survive into the stampede.[295] Very few stampeders married Hän women, and very few Hän women worked as prostitutes.[296] "Respectable" white women would avoid associating with Native women or prostitutes: those that did could cause scandal.[297]

End of the gold rush

By 1899 telegraphy stretched from Skagway, Alaska to Dawson City, Yukon, allowing instant international contact.[298] In 1898, the White Pass and Yukon Route railway began to be built between Skagway and the head of navigation on the Yukon.[299] When it was completed in 1900, the Chilkoot trail and its tramways were obsolete.[299] Despite these improvements in communication and transport, the rush faltered from 1898 on.[300] It began in summer 1898 when many of the prospectors arriving in Dawson City found themselves unable to make a living and left for home.[300] For those who stayed, the wages of casual work, depressed by the number of men, fell to $100 ($2,700) a month by 1899.[300] The world's newspapers began to turn against the Klondike gold rush as well.[300] In the spring of 1898 the Spanish–American War removed Klondike from the headlines.[301] "Ah, go to the Klondike!" became a popular phrase to express disgust with an idea.[300] Unsold, Klondike-branded goods had to be disposed of at special rates in Seattle.[300]

Another factor in the decline was the change in Dawson City, which had developed throughout 1898, metamorphosing from a ramshackle, if wealthy, boom town into a more sedate, conservative municipality.[298] Modern luxuries were introduced, including the "zinc bath tubs and pianos, billiard tables, Brussels carpets in the hotel dining rooms, menus printed in French and invitational balls" noted by historian Kathryn Winslow.[298] The visiting Senator Jerry Lynch likened the newly paved streets with their smartly dressed inhabitants to the Strand in London.[262] It was no longer as attractive a location for many prospectors, used to a wilder way of living.[300][298] Even the formerly lawless town of Skagway had become a stable and respectable community by 1899.[300]

The final trigger, however, was the discovery of gold elsewhere in Canada and Alaska, prompting a new stampede, this time away from the Klondike. In August 1898, gold had been found at Atlin Lake at the head of the Yukon River, generating a flurry of interest, but during the winter of 1898–99 much larger quantities were found at Nome at the mouth of the Yukon.[135][302][303] In 1899, a flood of prospectors from across the region left for Nome, 8,000 from Dawson alone during a single week in August.[135][302] The Klondike gold rush was over.[304]

Legacy

People

Only a handful of the 100,000 people who left for the Klondike during the gold rush became rich.[29] They typically spent $1,000 ($27,000) each reaching the region, which when combined exceeded what was produced from the gold fields between 1897 and 1901.[200] At the same time, most of those who did find gold lost their fortunes in the subsequent years.[305] They often died penniless, attempting to reproduce their earlier good fortune in fresh mining opportunities.[305] Businessman and miner Alex McDonald, for example, continued to accumulate land after the boom until his money ran out; he died in poverty, still prospecting. Antoine Stander, who discovered gold on Eldorado Creek, abused alcohol, dissipated his fortune and ended working in a ship's kitchen to pay his way.[306] The three discoverers had mixed fates. George Carmack left his wife Kate—who had found it difficult to adapt to their new lifestyle—remarried and lived in relative prosperity; Skookum Jim had a huge income from his mining royalties but refused to settle and continued to prospect until his death in 1916; Dawson Charlie spent lavishly and died in an alcohol-related accident.[307][n 39]

The richest of the Klondike saloon owners, businessmen and gamblers also typically lost their fortunes and died in poverty.[309] Gene Allen, for example, the editor of the Klondike Nugget, became bankrupt and spent the rest of his career in smaller newspapers; the prominent gambler and saloon owner Sam Bonnifield suffered a nervous breakdown and died in extreme poverty.[309] Nonetheless, some of those who joined the gold rush prospered. Kate Rockwell, "Klondike Kate", for example, became a famous dancer in Dawson and remained popular in America until her death. Dawson City was also where Alexander Pantages, her business partner and lover, started his career, going on to become one of America's greatest theatre and movie tycoons.[310] The businesswoman Martha Black remarried and ultimately became the second female member of the Canadian parliament.[284][311]

The impact of the gold rush on the Native peoples of the region was considerable.[312] The Tlingit and the Koyukon peoples prospered in the short term from their work as guides, packers and from selling food and supplies to the prospectors.[71] In the longer term, however, especially the Hän people living in the Klondike region suffered from the environmental damage of the gold mining on the rivers and forests.[71] Their population had already begun to decline after the discovery of gold along Fortymile River in the 1880s but dropped catastrophically after their move to the reserve, a result of the contaminated water supply and smallpox.[232] The Hän found only few ways to benefit economically from the gold rush and their fishing and hunting grounds were largely destroyed; by 1904 they needed aid from the NWMP to prevent famine.[313]

Places

Dawson City declined after the gold rush. When journalist Laura Berton (future mother of Pierre Berton) moved to Dawson in 1907 it was still thriving, but away from Front Street, the town had become increasingly deserted, jammed, as she put it, "with the refuse of the gold rush: stoves, furniture, gold-pans, sets of dishes, double-belled seltzer bottles ... piles of rusting mining machinery—boilers, winches, wheelbarrows and pumps".[314] By 1912, only around 2,000 inhabitants remained compared to the 30,000 of the boom years and the site was becoming a ghost town.[315] By 1972, 500 people were living in Dawson whereas the nearby settlements created during the gold rush had been entirely abandoned.[316] The population has grown since the 1970s, with 1,300 recorded in 2006.[317]

During the gold rush, transport improvements meant that heavier mining equipment could be brought in and larger, more modern mines established in the Klondike, revolutionising the gold industry.[318][319] Gold production increased until 1903 as a result of the dredging and hydraulic mining but then declined; by 2005, approximately 1,250,000 pounds (570,000 kg) had been recovered from the Klondike area.[318][319][320] In the 21st century Dawson City still has a small gold mining industry, which together with tourism, drawing on the legacy of the gold rush, plays a role in the local economy. Many buildings in the center of the town reflect the style of the era.[321] Klondike River valley is affected by the gold rush by the heavy dredging that occurred after it.[322]

The port of Skagway also shrank after the rush, but remains a well-preserved period town, centered on the tourist industry and sight-seeing trips from visiting cruise ships.[323] Restoration work by the National Park Service began in 2010 on Jeff Smith's Parlor, from which the famous con man "Soapy" Smith once operated.[324] Skagway also has one of the two visitor centres forming the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park; the other is located in Seattle, and both focus on the human interest stories behind the gold rush.[325] By contrast, Dyea, Skagway's neighbour and former rival, was abandoned after the gold rush and is now a ghost town.[326] The railway built for prospectors through White Pass in the last year of the rush reopened in 1988 and is today only used by tourists, closely linked to the Chilkoot trail which is a popular hiking route.[327]

Culture

The events of the Klondike gold rush rapidly became embedded in North American culture, being captured in poems, stories, photographs and promotional campaigns long after the end of the stampede.[328] In the Yukon, Discovery Day is celebrated on the third Monday in August as a holiday, and the events of the gold rush are promoted by the regional tourist industries.[329][330] The events of the gold rush were frequently exaggerated at the time and modern works on the subject similarly often focus on the most dramatic and exciting events of the stampede, not always accurately.[331][332] Historian Ken Coates describes the gold rush as "a resilient, pliable myth", which continues to fascinate and appeal.[333]

Several novels, books and poems were generated as a consequence of the Klondike gold rush. The writer Jack London incorporated scenes from the gold rush into his novels set in the Klondike, including The Call of the Wild, a novel about a sledge dog.[53][334] His colleague, poet Robert W. Service, did not join the rush himself, although he made his home in Dawson City in 1908. Service created well-known poems about the gold rush, among them Songs of a Sourdough, one of the bestselling books of poetry in the first decade of the 20th century, along with his novel, The Trail of '98, which was written by hand on wallpaper in one of Dawson's log cabins.[53][335][336] The Canadian historian Pierre Berton grew up in Dawson where his father had been a prospector, and wrote several historical books about the gold rush, such as The Last Great Gold Rush.[337] The experiences of the Irish Micí Mac Gabhann resulted the posthumous work Rotha Mór an tSaoil (translated into English as The Hard Road to Klondike in 1962), a vivid description of the period.[338]

Some terminology from the stampede made its way into North American English like "Cheechakos", referring to newly arrived miners, and "Sourdoughs", experienced miners.[339][n 40] The photographs taken during the Klondike gold rush heavily influenced later cultural approaches to the stampede.[341] The gold rush was vividly recorded by several early photographers, for instance Eric Hegg; these stark, black-and-white photographs showing the ascent of the Chilkoot pass rapidly became iconic images and were widely distributed.[342] These pictures in turn inspired Charlie Chaplin to make the The Gold Rush, a silent movie, which uses the background of the Klondike to combine physical comedy with its character's desperate battle for survival in the harsh conditions of the stampede.[343] The photographs reappear in the documentary City of Gold from 1957 which, narrated by Pierre Berton, won prizes for pioneering the incorporation of still images into documentary film-making.[344] The Klondike gold rush, however, has not been widely covered in later fictional films; even The Far Country, a Western from 1955 set in the Klondike, largely ignores the unique features of the gold rush in favour of a traditional Western plot.[345] Indeed, much of the popular literature on the gold rush approaches the stampede simply as a final phase of the expansion of the American West, a perception critiqued by modern historians such as Charlene Porsild.[346]

Appendix

Maps of routes and goldfields

Dyea/Skagway routes and Dalton trail

-

Overview and close up of Dyea/Skagway route (middle route on left section of map). Each red frame represents the map to the nearest right. Dalton trail is shown to the left on the midsection of the map

Takou, Stikine and Edmonton routes

-

Takou and Stikine route. Red frame: Position of map on map of northern America. Lower right: Stikine route branch from Wrangell meets with branch from Ashcroft at Glenora. They continue along dashed lines. Middle: Takou route meets Stikine route at Teslin Lake. Both routes meet Dyea/Skagway route (dotted line) at upper left

-

Edmonton routes. Red frame: Position of map on map of northern America. Big arrow: All-Canadian route from Edmonton by rivers and portage to Yukon River via Pelly River. Small arrows: Back door route. Black solid line: McKenzie River most of the way. Upper left corner: Yukon River from Fort Yukon to Dawson City

Goldfields

-

Map of goldfields with Dawson City and Klondike River at top. Red dot: discovery on Bonanza Creek.

Chart of gold production in Yukon 1892-1912

-

Production of gold in Yukon around the Klondike Gold Rush.[1] 1896-1903: Increase after discovery at Klondike. 1903-1907: claims are sold; big scale methods take over.

Population growth of west coast cities 1890-1900

| City | 1890 | 1900 | Difference | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco | 298,997 | 342,782 | 43,785 | 15 |

| Portland | 46,385 | 90,426 | 44,041 | 95 |

| Tacoma | 36,006 | 37,714 | 1,708 | 5 |

| Seattle | 42,837 | 80,671 | 37,834 | 88 |

| Vancouver | 13,709 | 27,010 | 13,301 | 97 |

| Victoria | 16,841 | 20,919 | 4,078 | 24 |

Source: Alexander Norbert MacDonald, "Seattle, Vancouver and the Klondike," The Canadian Historical Review (September 1968), p. 246.[347]

Klondikers supply list

- 150 pounds (68 kg) bacon

- 400 pounds (180 kg) flour

- 25 pounds (11 kg) rolled oats

- 125 pounds (57 kg) beans

- 10 pounds (4.5 kg) tea

- 10 pounds (4.5 kg) coffee

- 25 pounds (11 kg) sugar

- 25 pounds (11 kg) dried potatoes

- 25 pounds (11 kg) dried onions

- 15 pounds (6.8 kg) salt

- 1 pound (0.45 kg) pepper

- 75 pounds (34 kg) dried fruits

- 8 pounds (3.6 kg) baking powder

- 8 pounds (3.6 kg) soda

- 0.5 pounds (0.23 kg) evaporated vinegar

- 12 ounces (340 g) compressed soup

- 1 can of mustard

- 1 tin of matches (for four men)

- Stove for four men

- Gold pan for each

- Set of granite buckets

- Large bucket

- Knife, fork, spoon, cup, and plate

- Frying pan

- Coffee and teapot

- Scythe stone

- Two picks and one shovel

- One whipsaw

- Pack strap

- Two axes for four men and one extra handle

- Six 8-inch (200 mm) files and two taper files for the party

- Draw knife, brace and bits, jack plane, and hammer for party

- 200 feet (61 m) 0.375-inch (9.5 mm) rope

- 8 pounds (3.6 kg) of pitch and 5 lb (2.3 kg). of oakum for four men

- Nails, 5 pounds (2.3 kg) each of 6, 8, 10 and 12 penny, for four men

- Tent, 10 by 12 feet (3.0 m × 3.7 m) for four men

- Canvas for wrapping

- Two oil blankets to each boat

- 5 yards (4.6 m) of mosquito netting for each man

- 3 suits of heavy underwear

- 1 heavy Mackinaw coat

- 2 pairs heavy woollen trousers

- 1 heavy rubber-lined coat

- 12 heavy wool socks

- 6 heavy wool mittens

- 2 heavy over shirts

- 2 pairs of heavy, snag proof rubber boots

- 2 pairs of shoes

- 4 pairs of blankets (for two men)

- 4 towels

- 2 pairs of overalls

- 1 suit of oil clothing

- Several changes of summer clothing

- Small assortment of medicines

The list was a suggestion of equipment and supplies sufficient to support a prospector for one year, generated by the Northern Pacific Railroad company in 1897. The total weight is approximately 1 ton, and the estimated cost amounted to $140 ($3,800).[348]

Timeline

1896

- Aug. 16 : Gold is discovered on Bonanza Creek by George Carmack and Skookum Jim

- Aug. 31 : First claim on Eldorado Creek by Antone Stander

1897

- Jan. 21: Wiliam Ogilvie sends news of Klondike gold to Ottawa

- Jul. 14: Excelsior arrives at San Francisco with first gold from Klondike and starts stampede

- Jul. 15: Portland arrives at Seattle

- Jul. 19: First ship leaves for Klondike

- Aug. 16: Ex-mayor Wood from Seattle leaves San Francisco on his ship Humboldt with prospectors for Klondike (reaches St. Michael Aug. 29 but is forced to spend the winter on Yukon River)

- Sep. 11: 10% royalty is established on gold mined in Yukon

- Sep. 27: People without supplies for the winter leave Dawson in search of food

- Nov. 8: Work begins on Brackett wagon road through White Pass

1898

- Feb. 25: Troops arrive at Skagway to maintain order. Collection of costums begins at Chilkoot summit

- Mar. 8: Vigilante activity against Soapy Smith starts at Skagway

- Apr. 3: Avalanche kills more than 60 at Chilkoot Pass

- Apr. 24: Spanish-American war begins

- May 1: Soapy Smith stages a military parade in Skagway

- May 27: Klondike Nugget begins publication in Dawson

- May 29: Ice goes out on Yukon River and flotilla of boats sets out for Dawson

- Jun. 8: First boat reaches Dawson

- Jun. 24: Sam Steele (NWMP) arrives at Dawson

- Jul. 28: Soapy Smith shot to death in Skagway

- Sep. 22: Gold found at Nome, Alaska

1899

- Jan. 27: The remnants of a relief expedition send out in winter 1897 finally reaches Dawson

- Feb. 16: First train from Skagway reaches the White Pass summit

- Apr. 26: Fire destroys business district in Dawson

- Aug.: 8000 prospectors leave Dawson for Nome ending the Klondike Gold Rush

Source: Berton, 2001, Chronology

Notes

- ↑ Also called the Yukon Gold Rush, the Alaska Gold Rush, the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush, the Canadian Gold Rush, and the Last Great Gold Rush.

- ↑ An estimated 14,000,000 ounces (400,000,000 g) of gold has been taken from the area (until 2013) of which half came from Bonanza Creek, and a quarter from Hunker Creek.[1]

- ↑ Some of the first prospectors had to supplement their income with fur trading in order to survive.[5]

- ↑ One member of the Hän later commented that "my people knew all the Klondike, but they never know nothing about gold."[4]

- ↑ To add even more confusion to the question of who deserved credit for the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek, Robert Henderson and many of his contemporaries threw his name into the ring. Recent historiography discusses the efforts of Henderson to obtain compensation for his missed opportunity. Despite the fact Henderson made disparaging remarks about Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie, there were many proponents in favor of a Canadian (i.e. Henderson) receiving credit for the strike instead of the American Carmack.[19]

- ↑ The initial broad estimates of the numbers involved in the stampede were produced by Pierre Berton, the classic secondary historian of the period, drawing on a number of sources, including the NWMP statistics generated along the trails.[30][31] The most recent academic work continues to accept these estimates, but further detailed analysis has been carried out, using the first, limited Yukon census by the NWMP that occurred in 1898 and the more detailed Federal census in 1901.[32] Historian Charlene Porsild has conducted extensive work on these records, comparing them to other documentary accounts of the period. This has generated improved statistics for the nationality and gender of those involved in the gold rush.[33]

- ↑ Prices in this article are given in US dollars throughout; at the time of the gold rush, the US and Canadian dollars were each attached to the gold standard and held equal value. For this reason the academic literature and contemporary accounts do not usually differentiate between gold rush prices quoted in US or Canadian dollars. Equivalent modern prices have been given in 2010 US dollars, to two significant digits. The equivalent prices of modern goods and services have been calculated using the Consumer Price Index (1:27). Larger sums, for example gold shipments, and all capital investment projects, including land prices, have been calculated using the relative share of GDP index (1:800).[36]

- ↑ Traditional historical analysis, as outlined by George Fetherling, has suggested around 80 percent were US citizens or recent immigrants to America. The 1898 census data suggests that 63 percent of Dawson City inhabitants at the time were American citizens, with 32 percent Canadian or British. As Charlene Porsild has described, however, the census data for the period is inconsistent in how it asked questions about citizenship and place of birth. Porsild argues that the level of participation from those born in the US, as opposed to recent immigrants or temporary residents, may have been as low as 43 percent, with Canadian and British born members of the gold rush in the majority.[43][45]

- ↑ Although Adney's work was not well-known at the time, his 1900 work The Klondike Stampede has become highly regarded by modern historians as a relatively accurate and modest account of the gold rush.[52]

- ↑ For example, he worked as a river pilot on the rapids of Whitehorse during the summer of 1898.[53]

- ↑ The range of Klondike-themed goods was huge, from special food to glasses, boots, cigars, medicines, soup, blankets, and stoves.[56] It included some unusual offers such as a special Klondike bicycle, "ice bicycles", a wind-powered "boat sled", a "snow train", clockwork gold pans, and an X-ray gold detector designed by Nikola Tesla.[57]

- ↑ The weather could both be a help and an obstacle. Winter travel meant deep snow and treacherous ice. However, the mud that formed each spring and fall would be frozen and snow would cover the sharp, jagged rocks that the traveller would have to avoid in the summer.[62] In theory, it was possible to travel even during winter using teams of dogs, but if the temperature dropped significantly even dog sled teams would have to pause and take shelter.[63]

- ↑ Before the rush the price of such animals was $3–5 ($81–135).[67]

- ↑ On the other hand, competition among railways to attract Klondikers led to a reduction in train fares.[73]

- ↑ Former mayor of Seattle W. D. Wood led a party that tried to reach Dawson by this route. They too had to spend the winter along the frozen Yukon River, eating the supplies that Wood had hoped to sell at a profit in Dawson. Now he was forced to sell at his purchase price.[75]

- ↑ Jack London, who took the White Pass trail, has one of his fictional characters describe how the prospectors treated their horses: "Men shot them, worked them to death and when they were gone, went back to the beach and bought more ... Their hearts turned to stone—those which did not break—and they became beasts, the men on the Dead Horse Trail."[82]

- ↑ A typical prospector would carry around 65 pounds (29 kg) each time, moving it forward in five-mile stages before returning to pick up the next load. Once the whole ton of supplies had been moved, the next stage could begin. A prospector carrying the equipment alone would need thirty round journeys for each stage. In total, this would have come to 2,500 miles (4,000 km) by the end of the trail at Lake Bennett.[64]

- ↑ Though not seen on the picture, prospectors, who were going back down from the Chilkoot Pass for more equipment, would use slides carved in the ice near the stairs.[84]

- ↑ Horses abandoned before the summit were later rounded up and shot.[88]

- ↑ Around 70 people were initially believed to have been buried by the snow with between six and nine people subsequently rescued; however, the final toll remains uncertain.[94]