Ken Adam

| Sir Ken Adam | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg) Adam in 2012 | |

| Born |

Klaus Hugo Adam 5 February 1921 Berlin, Germany |

| Died |

10 March 2016 (aged 95) London, UK |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | Kenneth Hugo Adam |

| Education | St. Paul's School, London |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Years active | 1940–2003 |

| Known for | Air force pilot, production designer |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Letitzia (m. 1952–2016; his death) |

| Awards |

BAFTA for Dr. Strangelove (1964) BAFTA for The IPCRESS File (1965) Academy Award for Barry Lyndon (1975) Academy Award for The Madness of King George (1994) |

|

Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Rank | Flight lieutenant |

| Unit | No. 609 Squadron |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Sir Kenneth Hugo Adam, OBE (born Klaus Hugo Adam; 5 February 1921 – 10 March 2016) was a British movie production designer, best known for his set designs for the James Bond films of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as for Dr. Strangelove. He won two Academy Awards for Best Art Direction. Born in Berlin, he relocated to England with his Jewish family at the age of 13 soon after the Nazis came to power, and was one of only three German-born pilots in the British Royal Air Force during the Second World War.

Early life and education

Adam was born in Berlin to a Jewish family, the son of a former Prussian cavalryman.[1] He was the son of Lilli (née Saalfeld), who operated a boarding house, and Fritz Adam, who ran a successful high-fashion clothing store.[2] The company S.Adam (Berlin, Leipziger Straße/Friedrichstraße) was established in 1863 by Saul Adam.[3] Adam was educated at the Französisches Gymnasium Berlin (Berlin French school), and the family had a summer house on the Baltic.[1]

The same year the Nazi Party rose to power, the family's shop went bankrupt.[4] Adam watched the Reichstag fire from the Tiergarten. The family relocated to England in 1934.[1]

England

Adam was 13 years old when his family moved to England.[5] He went to St. Paul's School in London, and then attended University College London and Bartlett School of Architecture, training to be an architect.[6]

Career

RAF service

When World War II began, the Adam family were German citizens and could have been interned as enemy aliens. Adam was able to join the Pioneer Corps, a support unit of the British Army open to citizens of Axis countries resident in the UK and other Commonwealth countries, provided they were not considered a risk to security. Adam was seconded to design bomb shelters.[4] In 1940, Adam successfully applied to join the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve as a pilot. Adam was trained as a pilot by British actor Michael Rennie, and was one of only three German-born pilots in the wartime RAF.[7] As such, if he had been captured by the Germans, he was liable to execution as a traitor, rather than being treated as a prisoner of war.[8] Flight Lieutenant Adam joined No. 609 Squadron at RAF Lympne on 1 October 1943.[9][10] He was nicknamed “Heinie the tank-buster” by his comrades for his daring exploits.[4] The squadron flew the Hawker Typhoon, initially in support of USAAF long-range bombing missions over Europe.[10] Later they were employed in support of ground troops, including at the battle of the Falaise Gap, in Normandy after D-Day.[4] In 1944, his brother Denis joined No. 183 Squadron, joining Adam in No. 123 Wing.[10]

Career, honors and death

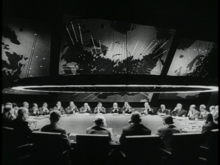

Adam entered the film industry as a draughtsman on This Was a Woman (1948). He met his Italian wife Maria Letizia while filming in Ischia, and they married on 16 August 1952.[1] His first major screen credit was as production designer on the British thriller Soho Incident (1956). In the mid-1950s, he worked (uncredited) on the epics Around the World in 80 Days (also 1956) and Ben-Hur (1959), directed by William Wyler. His first major credit was for the horror film, Night of the Demon (1957), directed by Jacques Tourneur, and he was also the production designer on several films directed by Robert Aldrich. He was hired for the first James Bond film, Dr. No (1962). For Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964), his work was described by the British Film Institute (BFI) as "gleaming and sinister."[1][11] Steven Spielberg even called it, "the best set that's ever been designed."[12] He turned down the opportunity to work on Kubrick's next project, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), after he found out that Kubrick had been working with NASA for a year on space exploration, and that would put him at a disadvantage in developing his art.[1]

This enabled Adam to make his name with his innovative, semi-futuristic sets for further James Bond films, such as Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967), and Diamonds Are Forever (1971). The supertanker set for The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) was constructed in the largest sound stage in the world, at the time. It was lit by Stanley Kubrick in secret.[13] His last Bond film was Moonraker (1979). Writing for The Guardian in 2005, journalist Johnny Dee claimed: "His sets for the seven Bond films he worked on [...] are as iconic as the movies themselves and set the benchmark for every blockbuster".[14]

Adam's other film credits include The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), the Michael Caine espionage thriller The Ipcress File (1965) and its sequel Funeral in Berlin (1966), the Peter O'Toole version of Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969), Sleuth (1972), Salon Kitty (1976), Agnes of God (1985), Addams Family Values (1993), and The Madness of King George (1994).[11][15] He was also a visual consultant on the film version of Pennies from Heaven (1981), adapted from Dennis Potter's television serial.[15]

Adam returned to work with Kubrick on Barry Lyndon (1975), for which he won his first Oscar. The BFI noted the film's "contrastingly mellow Technicolor beauties" in its depiction of the 18th century.[11][16] He also designed the famous car for the film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), which was produced by the same team as the James Bond film series.[16] During the late 1970s, he worked on storyboards and concept art for Star Trek: Planet of the Titans, then in pre-production. The film was eventually shelved by Paramount Pictures.[17]

Adam was a jury member at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival and the 49th Berlin International Film Festival.[18] In 1999, during the Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition "Ken Adam – Designing the Cold War", Adam spoke on his role in the design of film sets associated with the 1960s through the 1980s.[1]

Adam was naturalised as a British citizen, and was awarded the OBE for services to the film industry. In 2003, Adam was knighted for services to the film industry and Anglo-German relations.[10]

Adam died on 10 March 2016 at his home in London, following a short illness. He was 95 years old.[19]

Ken Adam Archive at the Deutsche Kinemathek

In September 2012, Adam handed over his entire body of work to the Deutsche Kinemathek. The collection comprises approximately 4,000 sketches for films from all periods, photo albums to individual films, storyboards of his employees, memorabilia, military medals, and identity documents, as well as all cinematic awards, including Adam's two Academy Awards.[7][20]

Awards

- 1964 – British Film Academy Award for Dr. Strangelove.[21]

- 1965 – British Film Academy Award for The IPCRESS File.[21]

He was also BAFTA-nominated for Goldfinger, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Sleuth, Barry Lyndon, The Spy Who Loved Me, and The Madness of King George.[21]

- 1975 – Academy Award for Best Art Direction, for his recreation of 18th century England in Barry Lyndon.[19]

- 1994 – Academy Award for Best Art Direction, for his work on The Madness of King George.[22]

He was also nominated for Academy Awards for his work on Around the World in Eighty Days, The Spy Who Loved Me, and Addams Family Values.[23]

He received the Art Directors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001.[24]

- 2003 – Ciak di Corallo, a career award from the Ischia Film Festival.[25]

Bibliography

- Adam, Ken; Sylvester, David (1999). Moonraker, Strangelove and Other Celluloid Dreams: The Visionary Art of Ken Adam. London: Phillip Galgiani. ISBN 978-1-870814-27-0.

- Adam, Ken; Frayling, Christopher (2008). Ken Adam Designs the Movies: James Bond and Beyond. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51414-6.

- Frayling, Christopher (2005). Ken Adam and the Art of Production Design. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22057-1.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Harrod, Horatia (28 September 2008). "Ken Adam: the man who drew the Cold War". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ http://www.filmreference.com/film/23/Ken-Adam.html

- ↑ "S. Adam Fashion House". Beuth University of Applied Sciences Berlin. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Phillips, Martin (25 April 2009). "Sir Ken Adam". The Sun. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ↑ Madigan, Nick (21 February 2002). "Ken Adam: designer behind 'Bond' movies". Variety. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Monahan, Mark (14 January 2006). "Film-makers on film: Ken Adam". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- 1 2 Farber, Stephen (14 March 2015). "Production designer Ken Adam looks back at 'Goldfinger,' other films". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Vishnevetsky, Ignatiy (10 March 2016). "R.I.P. Ken Adam, production designer for James Bond and Stanley Kubrick". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Frayling (2005): p. 23-41

- 1 2 3 4 "Ken Adam". 609 (West Riding) Squadron Archive. 2002. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Adam, Ken (1921–)". BFI. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ "Kubrick recalled by influential set designer Sir Ken Adam". BBC.com. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Frayling (2005): p. 131

- ↑ Dee, Johnny (17 September 2005). "Licensed to drill". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Ken Adam – Filmography". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- 1 2 Frayling (2005): p. 165-171

- ↑ Reeves-Stevens, Judith; Reeves-Stevens, Garfield (1997). Star Trek: Phase II: The Lost Series (2nd ed.). New York: Pocket Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0671568399.

- ↑ "1999 Juries". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- 1 2 "Sir Ken Adam, James Bond production designer, dies aged 95". BBC News. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Conrad, Andreas (4 September 2012). "James Bonds Chefdesigner". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 "BAFTA Awards Search: Ken Adam". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ "The 67th Academy Awards (1995) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "The 66th Academy Awards (1994) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ↑ "6th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards". Art Directors Guild. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ "Roll of honour (by year) – I edizione 2003". Ischia Film Festival. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

Further reading

- Smoltczyk, Alexander (2002). James Bond, Berlin, Hollywood – Die Welten des Ken Adam (in German). Berlin: Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung. ISBN 978-3-87584-069-8.

- Kissling-Koch, Petra (2012). Macht(t)räume: Der Production Designer Ken Adam und die James-Bond-Filme (in German). Berlin: Bertz + Fischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86505-396-1.

- Christie, Ian; Adam, Ken (2012). "Architect of Dreams". Patek Philippe International Magazine. III (7): 56.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ken Adam. |

- Ken Adam at the Internet Movie Database

- Ken Adam at BFI Screenonline

- Ken Adam at Web of Stories

- Imperial War Museum Interview from 1997

- Imperial War Museum Interview from 1997

- Imperial War Museum Interview from 2009