Jungle Carbine

| Rifle No 5 Mk I (aka Lee–Enfield No 5 Mk I, aka Lee–Enfield Jungle Carbine) | |

|---|---|

Rifle No 5 Mk I at the Yad Mordechai battlefield reconstruction site | |

| Type | Service rifle |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1944–Present |

| Used by |

United Kingdom Commonwealth of Nations |

| Wars |

World War II Korean War Malayan Emergency Bougainville Civil War[1] British Post-WWII colonial conflicts |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Royal Ordnance Factory Fazakerley, Birmingham Small Arms Company |

| Designed | 1944 |

| Produced | 1944–1947 |

| Number built | 251,368 total; 81,329 (BSA Shirley), 169,807 (ROF Fazakerley)[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 7 lb 1 oz (3.20 kg), unloaded |

| Length | 39.5 in (1,003 mm) |

| Barrel length | 18.8 in (478 mm) |

|

| |

| Cartridge | .303 Mk VII SAA Ball |

| Calibre | .303 British |

| Action | Bolt action |

| Rate of fire | 20–30 rounds/minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,250 ft/s (686 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 500 yd (457 m) |

| Maximum firing range | 200–800 yd (183–732 m) sight adjustments |

| Feed system | 10-round magazine, loaded with 5-round charger clips |

| Sights | Flip-up rear aperture sights, fixed-post front sights |

Jungle Carbine was an informal term used for the Rifle No. 5 Mk I[3] which was a derivative of the British Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk I, designed not for jungle fighting but in response to a requirement for a "Shortened, Lightened" version of the No.4 rifle for airborne forces in the European theatre of operations. The end of the war in Europe overtook widespread issue of the No.5 and most of the operational use of this rifle occurred in post-war colonial campaigns such as the Malayan emergency, where engagement ranges tended to be shorter and its handier size and reduced weight were an advantage. This is where the "Jungle Carbine" nickname comes from. Production began in March 1944, and finished in December 1947.[4]

Military service

The term "Jungle Carbine" was colloquial and never officially applied by the British Armed Forces,[5] but the Rifle No. 5 Mk I was informally referred to as the "Jungle Carbine" by British and Commonwealth troops during World War II and the Malayan Emergency.[3]

The No. 5 was about 100 mm shorter and nearly a kilogram lighter than the No. 4 from which it was derived. A number of "lightening cuts" were made to the receiver body and the barrel, the bolt knob drilled out, woodwork cut down to reduce weight and had other new features like a flash suppressor and a rubber buttpad to help absorb the increased recoil and to prevent slippage on the shooters clothing while aiming.[6] Unlike modern recoil pads the No. 5 buttpad significantly reduced the contact area with the users shoulder increasing the amount of felt recoil of the firearm. According to official recoil tests the No. 4 rifle yielded 10.06 ft·lbf (13.64 J) free recoil energy and the No. 5 carbine 14.12 ft·lbf (19.14 J). Of the No. 5 carbine 4.06 ft·lbf (5.50 J) extra recoil energy 1.44 ft·lbf (1.95 J) was caused by adding the conical flash suppressor.[7] The No. 5 iron sight line was also derived from the No. 4 marks and featured a rear receiver aperture battle sight calibrated for 300 yd (274 m) with an additional ladder aperture sight that could be flipped up and was calibrated for 200–800 yd (183–732 m) in 100 yd (91 m) increments. It was used in the Far East and other Jungle-type environments (hence the "Jungle Carbine" nickname) and was popular with troops because of its light weight (compared to the SMLE and Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk I rifles then in service) and general ease of use,[8] although there were some concerns from troops about the increased recoil due to the lighter weight.[3]

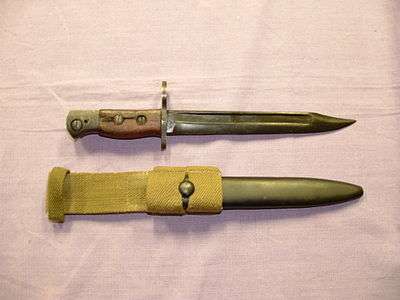

Due to the large conical flash suppressor, the No 5 Mk I could only mount the No. 5 blade bayonet, which was also designed to serve as a combat knife if needed.[9]

A No. 5 Mk 2 version (or, more accurately, versions, as several were put forward) of the rifle was proposed (including changes such as strengthening the action to enable grenade-firing, and mounting the trigger from the receiver instead of on the trigger guard), but none of them was ever put into production and there was subsequently no No. 5 Mk 2 rifle in service.[10] Similarly, a number of "takedown" models of No. 5 Mk I rifle intended for Airborne use were also trialled, but were not put into production.[11]

Wandering Zero

One of the complaints leveled against the No. 5 Mk I rifle by soldiers was that it had a "wandering zero" — i.e., the rifle could not be "sighted in" and then relied upon to shoot to the same point of impact later on.[3]

Tests conducted during the mid to late 1940s appeared to confirm that the rifle did have some accuracy issues, most likely relating to the lightening cuts made in the receiver, combined with the presence of a flash suppressor on the end of the barrel.,[12] and the British Government officially declared that the Jungle Carbine's faults were "inherent in the design" and discontinued production at the end of 1947.[13]

However, modern collectors and shooters have pointed out that no Jungle Carbine collector/shooter on any of the prominent internet military firearm collecting forums has reported a confirmed "wandering zero" on their No. 5 Mk I rifle,[3] leading to speculation that the No. 5 Mk I may have been phased out largely because the British military did not want a bolt-action rifle when most of the other major militaries were switching over to semi-automatic longarms[3] such as the M1 Garand, SKS, FN Model 1949 and MAS-49.

Nonetheless, it has also been pointed out by historians and collectors that the No. 5 Mk I must have had some fault not found with the No. 4 Lee–Enfield (from which the Jungle Carbine was derived), as the British military continued with manufacture and issue of the Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk 2 rifle until 1957,[14] before finally converting to the L1A1 SLR.[15]

Post-war non-military conversions

Though they did not invent the name, the designation "Jungle Carbine" was used by the Golden State Arms Corporation in the 1950s and 1960s to market commercially sporterised military surplus Lee–Enfield rifles under the "Santa Fe" brand.[16] Golden State Arms Co. imported huge numbers of SMLE Mk III* and Lee–Enfield No. 4 rifles and converted them to civilian versions of the No. 5 Mk I and general sporting rifles for the hunting and recreational shooting markets in the US, marketing them as "Santa Fe Jungle Carbine" rifles and "Santa Fe Mountaineer" rifles, amongst other names.[16]

This has led to a lot of confusion regarding the identification of actual No. 5 Mk I "Jungle Carbine" rifles, as opposed to the post-war civilian sporting rifles marketed under the same name.[3] The easiest way to identify a "Jungle Carbine" rifle is to look for the markings on the left hand side of the receiver; a genuine No. 5 will have "Rifle No 5 Mk I" electrostencilled there,[17] while a post-war conversion will generally have either no markings or markings from manufacturers who did not make the No. 5 Mk I (for example, Savage or Long Branch).[3] Santa Fe "Jungle Carbine" rifles are so marked on the barrel.[16]

Companies such as the Gibbs Rifle Company and Navy Arms in the U.S. have produced and sold completely re-built Enfields of all descriptions, most notably their recent "#7 Jungle Carbine" (made from Ishapore 2A1 rifles) and the "Bulldog" or "Tanker" carbine rifles, which are also fashioned original SMLE and No. 4 rifles.[18]

Notes

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NOJIw672aA

- ↑ Skennerton (2007) p.244

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wilson (2006)

- ↑ Skennerton (2007), p.246

- ↑ Skennerton (1994), p.5

- ↑ Skennerton (1994), p.7

- ↑ Lee Enfield No.5 "jungle carbine"

- ↑ Skennerton (1994) p.7

- ↑ Skennerton (2007), p. 406

- ↑ Skennerton (2007) p.245

- ↑ Skennerton (2007) p. 204

- ↑ Skennerton (1994) p.8

- ↑ Skennerton (1994), p.8

- ↑ Skennerton (2007), p.559

- ↑ Skennerton (2001), p.5

- 1 2 3 Skennerton (2007) p.380

- ↑ Skennerton (2007) p.499

- ↑ Skennerton (2007), p.382

References

- Skennerton, Ian (2007). The Lee-Enfield. Gold Coast QLD (Australia): Arms & Militaria Press. ISBN 0-949749-82-6.

- Skennerton, Ian (1994). Small Arms Identification Series No. 4: .303 Rifle, No. 5 Mk I. Gold Coast QLD (Australia): Arms & Militaria Press. ISBN 0-949749-21-4.

- Skennerton, Ian (2001). Small Arms Identification Series No. 12: 7.62mm L1 & C1 F.A.L. Rifles. Gold Coast QLD (Australia): Arms & Militaria Press. ISBN 0-949749-21-4.

- Wilson, Royce (May 2006). Jungle Fever- The Lee-Enfield .303 Rifle. Australian Shooter Magazine.