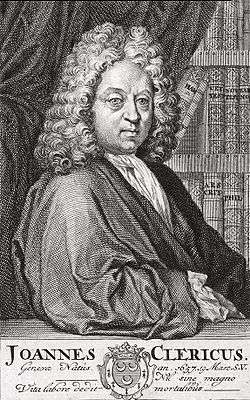

Jean Leclerc (theologian)

Jean Le Clerc, also Johannes Clericus (March 19, 1657 in Geneva – January 8, 1736 in Amsterdam), was a Swiss theologian and biblical scholar. He was famous for promoting exegesis, or critical interpretation of the Bible, and was a radical of his age. He parted with Calvinism over his interpretations and left Geneva for that reason.

Early life

His father, Stephen Le Clerc, was professor of Greek in Geneva. The family originally belonged to the neighborhood of Beauvais in France, and several of its members acquired some name in literature. Jean Le Clerc applied himself to the study of philosophy under Jean-Robert Chouet (1642-1731) the Cartesian, and attended the theological lectures of Philippe Mestrezat, Franz Turretin and Louis Tronchin (1629-1705). In 1678-1679 he spent some time in Grenoble as tutor in a private family; on his return to Geneva he passed his examinations and received ordination. Soon afterwards he went to Saumur.

In 1682 he went to London, where he remained for six months, preaching on alternate Sundays in the Walloon church and in the Savoy Chapel. Due to political instability, he moved to Amsterdam, where he was introduced to John Locke and to Philipp van Limborch, professor at the Remonstrant college. He later included Locke in the journals he edited; and the acquaintance with Limborch soon ripened into a close friendship, which strengthened his preference for the Remonstrant theology, already favorably known to him by the writings of his grand-uncle, Stephan Curcellaeus (d. 1645) and by those of Simon Episcopius.

A last attempt to live at Geneva, made at the request of relatives there, satisfied him that the theological atmosphere was uncongenial, and in 1684 he finally settled in Amsterdam, first as a moderately successful preacher, until ecclesiastical jealousy reportedly shut him out from that career, and afterwards as professor of philosophy, belles-lettres and Hebrew in the Remonstrant seminary. This appointment, which he owed to Limborch, he held from 1684, and in 1725 on the death of his friend he was called to occupy the chair of church history also.

Apart from literary work, Le Clerc's life at Amsterdam was uneventful. In 1691 he married a daughter of Gregorio Leti. From 1728 onward he was subject to repeated strokes of paralysis, and he died 8 years later, on 8 January.

Views

His suspected Socinianism was the cause, it is said, of his exclusion from the chair of dogmatic theology.

Published works

In 1679 in Saumur were published Literii de Sancto Amore Epistolae Theologicae (Irenopoli: Typis Philalethianis), usually attributed to Leclerc. They deal with the doctrine of the Trinity, the Hypostatic union of the two natures in Jesus Christ, original sin, and other topics, in a manner unorthodox for the period. In 1685 he published with Charles Le Cène Entretiens sur diverses matières de théologie.[1]

In 1685 he published Sentimens de quelques theologiens de Hollande sur l'histoire critique du Vieux Testament composée par le P. Richard Simon, in which, while pointing out what he believed to be Richard Simon's faults, he advanced views of his own. These included: arguments against the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch; his views as to the manner in which the five books were composed; and his opinions on the subject of divine inspiration in general, in particular on the Book of Job, Book of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Canticles. Simon's Réponse (1686) drew from Le Clerc a Defence des sentimens in the same year, which was followed by a new Réponse (1687).

In 1692 appeared his Logica sive Ars Ratiocinandi, and also Ontologia et Pneumatologia; these, with the Physica sive de rebus corporeis (1696), are incorporated with the Opera Philosophica, which have passed through several editions. In his Logica, Le Clerc rewrites the Catholic Port-Royal Logique from a protestant Remonstrant perspective and supplements the Logique with analyses taken the Essay of his friend, John Locke.[2][3] In turn, Charles Gildon published a partial and unattributed translation of Le Clerc's Logica as the treatise "Logic; or, The Art of Reasoning" in the second (1712) and subsequent editions of John Brightland's Grammar of the English Tongue.[4] In 1728, Ephraim Chambers used Gildon's translation of Le Clerc's version of the Port-Royal Logique as one of his sources when he compiled his Cyclopaedia.[5] John Mills and Gottfried Sellius later translated Chambers's Cyclopaedia into French. Their translation was appropriated by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert as the starting point for their Encyclopédie.[6] In particular, the article on définition (1754) in the Encyclopédie can be traced through this chain of writers, editors, translators, and compilers to the Port-Royal Logique through the Logica of Jean Le Clerc.[7]

In 1693 his series of Biblical commentaries began with that on the Book of Genesis; the series was not completed until 1731. The portion relating to the New Testament books included the paraphrase and notes of Henry Hammond. Le Clerc's commentary challenged traditional views and argued the case for inquiry into the origin and meaning of the biblical books, It was hotly attacked on all sides.

His Ars Critica appeared in 1696, and, in continuation, Epistolae Criticae et Ecclesiasticae in 1700. Le Clerc produced a new edition of the Apostolic Fathers of Cotelerius (Jean-Baptiste Cotelier, 1627-1686), published in 1698. He also edited journals of book notices and reviews: the Bibliothèque universelle et historique (Amsterdam, 25 vols, 1686-1693), begun with J. C. de la Croze; the Bibliothèque choisie (Amsterdam, 28 vols, 1703-1713); and the Bibliothèque ancienne et moderne, (29 vols, 1714-1726).

Other works were Le Clerc's Parrhasiana ou penses sur des matires de critique, d'histoire, de morale, et de politique: avec la defense de divers ouvrages de M. L. C. par Théodore Parrhase (Amsterdam, 1699); and Vita et opera ad annum MDCCXL, amici ejus opusculu in philosophicis Clerici operibus subjiciendum, also attributed to himself. The supplement to Hammond's notes was translated into English in 1699, Parrhesiana, or Thoughts on Several Subjects, in 1700, the Harmony of the Gospels in 1701, and Twelve Dissertations out of 211. Other works include Editionen von Texten der Kirchenväter, and Harmonia evangelica, 1700.

Notes

- ↑ Larminie, Vivienne. "Le Cène. Charles". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16260. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Arnauld, Antoine; Nicole, Pierre (1662). La logique ou l'Art de penser. Paris: Jean Guignart, Charles Savreux, & Jean de Lavnay.

- ↑ Locke, John (1690). An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. London: Thomas Bassett.

- ↑ Gildon, Charles (1714). A Grammar of the English Tongue (3 ed.). London: John Brightland.

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. London: James and John Knapton, John Darby, and others.

- ↑ Diderot, Denis; d'Alembert, Jean le Rond (1751–1772). Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une société de gens de lettres. Paris: Briasson, David l'aîné, Le Breton, and Durand.

- ↑ Bocast, Alexander K (2016). Chambers on Definition. McLean: Berkeley Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-945208-00-3.

References

- Vincent, Benjamin (1877) "Leclerc, Jean (1657-1736)" A Dictionary of Biography, Past and Present: Containing the chief events in the lives of eminent persons of all ages and nations Ward, Lock, & Co., London;

- Hargreaves- Mawdsley, W.N. (1968) "Leclerc, Jean (1657-1736)" Everyman's Dictionary of European Writers Dutton, New York, ISBN 0-460-03019-1 ;

- Watson, George (ed.) (1972) "Leclerc, Jean (1657-1736)" The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, ISBN 0-521-07255-7 ;

- Lueker, Erwin L. (ed.) (1975) "Arminianism" Lutheran Cyclopedia, accessed November 7, 2006 ;

- Pitassi, Maria Cristina (1987) Entre croire et savoir. Le problème de la méthode critique chez Jean Le Clerc, E.J. Brill, Leiden ;

- Le Clerc, Jean (1987-1997) "Epistolario", 4 vols., ed. M. e M.G. Sina, Leo S. Olschki, Firenze, ISBN 88-222-3495-2, 88 222 3872 9, 88 222 4211 4, 88 222 4536 9 ;

- Yolton, John W. et al. (1991) "Leclerc, Jean (1657-1736)" The Blackwell Companion to the Enlightenment Basil Blackwell, Cambridge, MA, ISBN 0-631-15403-5 ;

- Walsh, Michael (ed.) (2001) "Leclerc, Jean (1657-1736)" Dictionary of Christian Biography Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN, ISBN 0-8146-5921-7 ;

- Asso, Cecilia (2004) "Erasmus redivivus. alcune osservazioni sulla filologia neotestamentaria di Jean Le Clerc" Vico nella storia della filologia, ed. Silvia Caianiello e Amadeu Viana, Alfredo Guida, Napoli, ISBN 88-7188-860-X ;

- Bocast, Alexander K (2016). Chambers on Definition. McLean: Berkeley Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-945208-00-3

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.