James Sowerby

| James Sowerby | |

|---|---|

.jpg) James Sowerby painted by Thomas Heaphy (1816) | |

| Born |

21 March 1757 Lambeth, London, England |

| Died |

25 October 1822 (aged 65) Lambeth, London, England |

| Education | Royal Academy in London |

| Occupation | Illustrator, naturalist, publisher |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Brettingham De Carle |

| Children | James de Carle, George Brettingham, Charles Edward |

| Parent(s) | John Sowerby, Arabella Goodspeed |

James Sowerby (21 March 1757 – 25 October 1822) was an English naturalist and illustrator. Contributions to published works, such as A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland or English Botany, include his detailed and appealing plates. The use of vivid colour and accessible texts were intended to reach a widening audience in works of natural history.[1]

Biography

James Sowerby was born in Lambeth, London, his parents were named John and Arabella. Having decided to become a painter of flowers his first venture was with William Curtis, whose Flora Londinensis he illustrated. Sowerby studied art at the Royal Academy and took an apprenticeship with Richard Wright. He married Anne Brettingham De Carle and they were to have three sons: James De Carle Sowerby (1787–1871), George Brettingham Sowerby I (1788–1854) and Charles Edward Sowerby (1795–1842), the Sowerby family of naturalists. His sons and theirs were to contribute and continue the enormous volumes he was to begin and the Sowerby name was to remain associated with illustration of natural history.

An early commission for Sowerby was to lead to his prominence in the field when the botanist L'Hértier de Brutelle invited Sowerby to provide the plates for his monograph, Geranologia, and two later works. He also came to the notice of William Curtis, who was undertaking a new type of publication. Early volumes of the first British botany journal, The Botanical Magazine, contained fifty-six of his illustrations.

In 1790, he began the first of several huge projects: a 36-volume work on the botany of England that was published over the next 24 years, contained 2592 hand-colored engravings and became known as Sowerby's Botany. An enormous number of plants were to receive their formal publication, but the authority for these came from the unattributed text written by James Edward Smith.[2]

It was the inclusion of science in the form of natural history, such as the thousands of botanical supplied by Smith or his own research, that distinguished Sowerby's art from early forms of still life. This careful description of the subjects, drawing from specimens and research, was in contrast to the flower painting of the Rococo period found illuminating the books and galleries of a select audience. Sowerby intended to reach an audience whose curosity for gardening and the natural world could be piqued by publishing the attractive and more affordable works. The appealing hand coloured engravings also became highly valued by researchers into the new fields of science.[2]

His next project was of similar scale: the Mineral Conchology of Great Britain, a comprehensive catalog of many invertebrate fossils found in England, was published over a 34-year time-span, the latter parts by his sons James De Carle Sowerby and George Brettingham Sowerby I. The finished worked contains 650 colored plates distributed over 7 volumes.

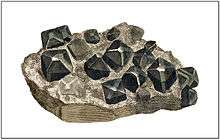

He also developed a theory of colour and published two landmark illustrated works on mineralogy: the British Mineralogy (1804–1817) and as a supplement to it the Exotic Mineralogy (1811–1820).

.jpg)

Sowerby retained the specimens used in the expansive volumes he helped to produce. Many notable geologists, and other scientists of the day were to lend or donate specimens to his collection. He had intended that his

some thousands of minerals, many not known elsewhere, a great variety of fossils, most of the plants of English Botany about 500 preserved specimens or models of fungi, quadrupeds, birds, insects, &c. all the natural production of Great Britain[3]

become the foundation of a museum. The addition of a room at the rear of his residence, housing this collection, was to see visits from the president of the Royal Society, Joseph Banks, and Charles Francis Greville who also lent to the informal institution. A much sought exhibit, one that was frequently chipped for samples, was the Yorkshire meteorite; this was sighted and collected in 1795, the first recorded English meteorite.[4]

Legacy

James' great grandson, the explorer and naturalist Arthur de Carle Sowerby continued the family tradition, providing many specimens for the British Museum and museums in Shanghai and Washington D.C.[5]

Bibliography

James Sowerby produced a large corpus of work that appeared in many different publications and journals. Some of the works begun by the paterfamilias of the Sowerby's was to be completed only by the generations that followed. His illustrations, publication and publishing concerns embraced many of the emergent fields of science. Besides the renowned botanical works, Sowerby produced extensive volumes on mycology, conchology, mineralogy and a seminal work on his colour system. He also wrote an instruction called A botanical drawing-book, or an easy introduction to drawing flowers according to nature.

- Florist's luxurians or the florist's delight, and;

- Sibthrop's Flora Graeca, 10 vols. 1806-40.

- Sowerby also supplied plates for Curtis's Flora Londinensis.

- English Botany or, Coloured Figures of British Plants, with their Essential Characters, Synonyms and Places of Growth, descriptions supplied by Sir James E. Smith, was issued as a part work over 23 years until its completion in 1813. This work was issued in 36 volumes with 2,592 hand-colored plates of British plants. He also published Exotic Botany in 1804.

- Smith's comprehensive work did not include Kingdom Fungi, Sowerby set out to supplement English Botany with his own text and descriptions. Coloured figures of English fungi or mushrooms, 4 vols. both appeared between 1789 and 1791.

- A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland Written by James Edward Smith and illustrated by James Sowerby, it was published by Sowerby between 1793 and 1795, becoming the first monograph on the Flora of Australia. It was prefaced with the intention of meeting the general interest in, and propagation of, the flowering species of the new antipodean colonies, while also containing a Latin and botanical description of the sample. Sowerby's own hand coloured engravings, based upon original sketches and specimens brought to England, were both descriptive and striking in depiction.

- Mineral Conchology of Great Britain Digital version

- British Mineralogy: Or Coloured figures intended to elucidate the mineralogy of Great Britain (R. Taylor and co., London) was published as parts between 1802 and 1817.

- Exotic Mineralogy: Or Coloured Figures of Foreign Minerals, as a Supplement to British Mineralogy[6] (1811), followed British Mineralogy and the scope was extended to include American specimens. Issued by subscription, the work ran to two volumes that comprised an incomplete 27 parts. Descriptions of rarities held in the 'mineral cabinets' of many notable collectors included 167 plates, brilliantly coloured by Sowerby and his family.

- A New Elucidation of Colours, Original Prismatic and Material: Showing Their Concordance in the Three Primitives, Yellow, Red and Blue: and the Means of Producing, Measuring and Mixing Them: with some Observations on the Accuracy of Sir Isaac Newton, London 1809. This work, given in homage to Isaac Newton, was to establish the importance of 'light and dark' in colour theory. He presents a theory of colour being composed of three basic colours: red, yellow and blue. Yellow, or gamboge as he had it, would become substituted by green in the later colour systems on which is what was based.[7]

- Familiar Lessons on Mineralogy and Geology (digital version), and other publications by John Mawe.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Henderson, Paul (2015). James Sowerby; the Enlightenment's natural historian. London: Kew Publishing with the Natural History Museum. ISBN 9781842465967.

- 1 2 Walsh, Huber M. (2003). "James Sowerby". Rare book - Authors. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

Unlike other flower painters of the time, whose work tended toward pleasing wealthy patrons, he worked directly with scientists.

- ↑ Sowerby's description. Conklin citing letter at British museum (Natural History)

- ↑ Conklin gives "Yorkshire meteorite". see Wold Newton meteorite (also called the Wold Cottage meteorite after a nearby house)

- ↑ Stevens, Keith (1998). Naturalist, Author, Artist, Explorer and Editor. Hong Kong Branch Royal Asiatic Society.

- ↑ Two variants of the title exist, this and Exotic Mineralogy: Or Coloured Figures of Such Foreign Minerals as are Not Likely to he Found in Great Britain, as a Supplement to British Mineralogy, Making Together a Complete Mineralogical Cabinet.

- ↑ "James Sowerby". colour systems. echo productions. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

he wishes to re-emphasise the significance of brightness and darkness, which after Newton had fallen into obscurity; and he wishes to clarify the difference which exists between colours.

- ↑ "James Sowerby (1757-1822)". The Mineralogical Record Museum of Art. Mineralogical Record Inc. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ IPNI. Sowerby.

- Conklin Lawrence H. (1995). "James Sowerby, his publications and works". Reprints of Conklin articles. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

N.B.: This article appeared in Mineralogical Record, volume 26, July–August, 1995.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Sowerby. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: James Sowerby |

- James Sowerby's Mineralogy

- Mineral conchology of Great Britain (digital reproduction)

- Original Pattern Plates for Mineral Conchology of Great Britain

- portrait

- Digital Scans of Sowerby's "English Botany, or, Coloured Figures of British Plants, with their Essential Characters, Synonyms, and Places of Growth" from History of Science Digital Collection: Utah State University