James Clark McReynolds

| James McReynolds | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office August 29, 1914 – January 31, 1941[1] | |

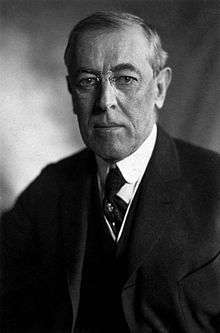

| Nominated by | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Horace Lurton |

| Succeeded by | James Byrnes |

| 48th United States Attorney General | |

|

In office March 15, 1913 – August 29, 1914 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | George Wickersham |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Gregory |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

February 3, 1862 Elkton, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died |

August 24, 1946 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater |

Vanderbilt University University of Virginia |

| Religion | Disciples of Christ |

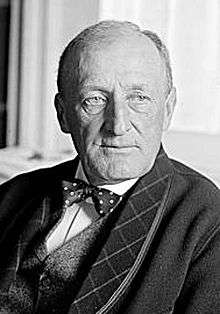

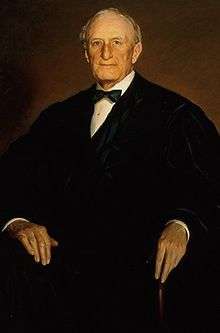

James Clark McReynolds (February 3, 1862 – August 24, 1946) was an American lawyer and judge who served as United States Attorney General under President Woodrow Wilson and as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He served on the Court from October 12, 1914 to his retirement on January 31, 1941, during the presidencies of Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was best known for his sustained opposition to the actions by Roosevelt and his overt anti-semitism. In his twenty-six years on the bench, McReynolds wrote more than 506 majority opinions for the court and 93 minority opinions against the New Deal. He was one of the "Four Horsemen" (together with Willis Van Devanter, George Sutherland, and Pierce Butler), who represented the opposition to Roosevelt's New Deal.

Early life

Born in Elkton, Kentucky, the county seat of Todd County, he was the son of John Oliver and Ellen (née Reeves) McReynolds, both members of the Disciples of Christ church.[2] The house in which he was born still stands;[3][upper-alpha 1] it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.[5] He graduated from the prestigious Green River Academy[6] and later matriculated at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, graduating with status one year later as a valedictorian in 1882. At the University of Virginia School of Law, where he studied under John B. Minor, "a man of stern morality and firm conservative convictions," McReynolds completed his studies in fourteen months and, again, graduated at the head of his class.[2] McReynolds received his law degree in 1884.

He was secretary to Senator Howell Edmunds Jackson, who later became an associate justice himself. McReynolds practiced law in Nashville and served for three years as an Adjunct professor of Commercial Law, Insurance, and Corporations at Vanderbilt University Law School,[2][7] and ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1896 as a "Goldbug" Democrat.[upper-alpha 2] As head of the Tennessee delegation to the 1896 Democratic Convention, he wrote the party's "sound money" plank.[7] Under Theodore Roosevelt he was Assistant Attorney General from 1903 to 1907, when he resigned to take up private practice with the noted law firm of Guthrie, Cravath, and Henderson in New York City.

Attorney General and Supreme Court tenure

While in private practice, he was retained by the Government in matters relating to enforcement of antitrust laws, particularly in proceedings against the "Tobacco trust" (see United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106 (1911))[8][9] and the combination of the anthracite coal railroads.[10] The case which brought him to the attention of President Wilson was the government's case against the American Tobacco Company, in which McReynolds presented the government's case, while the company was represented by Clarence Darrow and 17 other attorneys.[11]

On March 15, 1913, following the successful conclusion of this case, with Attorney General Wickersham's recommendation, Wilson appointed McReynolds as the 48th United States Attorney General where he remained until August 29, 1914. During his time in private practice, McReynolds earned a reputation as an ardent 'trust buster'[10][12] and continued working against trusts during his time as the US Attorney General.[10][12][13] In spite of his views on corporate monopolies, McReynolds was also very supportive of laissez-faire economic policies[14] and Wilson found him difficult to work with.[2][13][15][16]

On August 19, 1914, Wilson appointed him to the Supreme Court, to a seat vacated by Horace H. Lurton. McReynolds was confirmed by the United States Senate and received his commission the same day, starting with the new term on October 12, 1914.

When the Supreme Court Building opened in 1935, McReynolds, like most of the other justices, refused to move his office into the new building; he continued to work out of the office he maintained in his apartment. His reason was that with the country in the turmoil of the Great Depression, it was unconscionable to have spent so much money on a single building.[17]

Important opinions

In his 27 years on the bench, he authored 506 decisions, an average of just under 19 opinions for each term of the Court during his tenure. In addition, he authored 93 minority opinions against the New Deal.[18][19]

His fierce opposition in the face of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal legislation to fight the Great Depression led to his being labeled one of the "Four Horsemen", along with George Sutherland, Willis Van Devanter and Pierce Butler.[15] McReynolds voted to strike down the Tennessee Valley Authority in Ashwander v. TVA, the National Industrial Recovery Act in Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 in United States v. Butler, the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 in Carter v. Carter Coal Co., and the Social Security Act 42 U.S.C.A. § 301 et seq. in Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548, 57 S. Ct. 883, 81 L. Ed. 1279 (1937).[2] He continued to vote against New Deal measures after the Court's 1937 "switch" to upholding New Deal legislation. Howard Ball called McReynolds "the most strident Court critic of Roosevelt's New Deal programs".[20]

As a confirmed opponent of federal authority aimed toward social ends or economic regulation, he had the "single-minded passion of a zealot".[2] McReynolds was a "firm believer in laissez-faire economic theory" which he said was constitutionally enshrined.[2] See Lochner v New York. After the Lochner era ended in 1937—the Court's "switch in time that saved nine"—McReynolds became a dissenter.[16] Unrepentant after the court's about face through his 1941 retirement, his dissents decried the federal government's exercises of power. In Steward Machine Co. v. Davis 301 U.S. 548 (1937), he dissented from a decision of the Court upholding the Social Security Act. He wrote: "I can not find any authority in the Constitution for making the Federal Government the great almoner of public charity throughout the United States" (p. 603).[2]

Justice McReynolds wrote two early decisions using the Fourteenth Amendment to protect civil liberties: Meyer v. Nebraska 262 U.S. 390 (1923), and Pierce v. Society of Sisters 268 U.S. 510 (1925). Meyer involved a state law that prohibited the teaching of modern foreign languages in public schools. Meyer, who taught German in a Lutheran school, was convicted under this law. McReynolds wrote that the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment included an individual's right "to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, to establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his conscience, and generally to enjoy privileges, essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men". These two decisions survived the post-Lochner era.[16]

Pierce involved a challenge to a law forbidding parents to send their children to any but public schools. Justice McReynolds wrote the opinion for a unanimous Court, holding that the Act violated the liberty of parents to direct the education of their children. McReynolds wrote that "the fundamental liberty upon which all governments in this Union repose excludes any general power of the State to standardize its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only". These decisions were revived long after McReynolds departed from the bench, to buttress the Court's announcement of a constitutional right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut 381 U.S. 479 (1965), and later the constitutional right to abortion in Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

McReynolds authored the decision in United States v. Miller 307 U.S. 174 (1939), which was the only Supreme Court case that directly involved the Second Amendment until District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008.[19] Text of United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939) is available from: Findlaw Justia In the field of tax law, McReynolds wrote for the Court in Burnet v. Logan, 283 U.S. 404 (1931), a significant decision setting out the Court's doctrine regarding "open transactions".

McReynolds also wrote the dissent in the Gold Clause Cases, which required the surrender of all gold coins, gold bullion, and gold certificates to the government by May 1, 1933 under Executive Order 6102, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt.

Personality and conflicts

McReynolds was labeled "Scrooge" by journalist Drew Pearson.[upper-alpha 3] Chief Justice William Howard Taft thought him selfish, prejudiced, "and someone who seems to delight in making others uncomfortable … [H]e has a continual grouch, and is always offended because the court is doing something that he regards as undignified".[21][22] Taft also wrote that McReynolds was the most irresponsible member of the Court, and that "[i]n the absence of McReynolds everything went smoothly."[23]

Early on, his temperament affected his performance in the court.[15] For example, he deemed John Clarke, another Wilson appointee to the court, to be "too liberal" and refused to speak with him.[15] Clarke made an early decision to leave the Court, and McReynolds's antipathy was a factor given by Clarke.[24] However, another possible reason was his hope of an appointment by President Wilson as his representative to the nascent League of Nations, and writing to the President that he felt it was his "duty to devote what might remain to me of life and health and strength to doing what I could to cultivate public opinion in our country to having our government take some share in the effort which many other nations are making to devise some rational substitute for irrational war".[17] Indeed, McReynolds refused to sign the customary joint memorial letter given to departing members.[25] In a letter, Taft commented that "[t]his is a fair sample of McReynolds's personal character and the difficulty of getting along with him."[26]

Taft wrote that although he considered McReynolds an "able man", he found him to be "selfish to the last degree... fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known … one who delights in making others uncomfortable. He has no sense of duty … really seems to have less of a loyal spirit to the Court than anybody".[27] In 1929 McReynolds asked Taft to announce opinions assigned to him (McReynolds), explaining that "an imperious voice has called me out of town. I don't think my sudden illness will prove fatal, but strange things some time [sic] happen around Thanksgiving".[28] Duck hunting season had opened and McReynolds was off to Maryland for some shooting. In 1925, he left so suddenly on a similar errand that he had no opportunity to notify the Chief Justice of his departure. Taft was infuriated as two important decisions he wanted to deliver were delayed because McReynolds had not handed in a dissent before leaving.[29]

He would go into tirades about "un-Americans" and "political subversives."[2]

A blatant bigot,[15][upper-alpha 4][31] McReynolds would not accept "Jews, drinkers, blacks, women, smokers, married or engaged individuals" as law clerks.[32] Time "called him 'Puritanical', 'intolerably rude', 'savagely sarcastic', 'incredibly reactionary', and 'anti-Semitic'".[33][34][35] McReynolds refused to speak to Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish member of the Court, for three years following Brandeis's appointment and, when Brandeis retired in 1939, did not sign the customary dedicatory letter sent to justices on their retirement.[34][36] He habitually left the conference room whenever Brandeis spoke.[34] When Benjamin Cardozo's appointment was being pressed on President Herbert C. Hoover, McReynolds joined with fellow justices Pierce Butler and Willis Van Devanter in urging the White House not to "afflict the Court with another Jew".[37] When news of Cardozo's appointment was announced, McReynolds is claimed to have said "Huh, it seems that the only way you can get on the Supreme Court these days is to be either the son of a criminal or a Jew, or both."[38][39] During Cardozo's swearing-in ceremony, McReynolds pointedly read a newspaper,[38] and would often hold a brief or record in front of his face when Cardozo delivered an opinion from the bench.[40] Likewise, he refused to sign opinions authored by Brandeis.[13]

According to John Frush Knox (1907–1997), McReynolds's law clerk for one term, 1936–1937, following the seven-year clerkship of Maurice Mahoney, and one author of a memoir of his service, McReynolds never spoke to Cardozo at all.[32] McReynolds even absented himself from the memorial ceremonies held at the Supreme Court in honor of Cardozo.[39][41][42] He did not attend Felix Frankfurter's swearing-in, exclaiming "My God, another Jew on the Court!"[43]

In 1922, Taft proposed that members of the Court accompany him to Philadelphia on a ceremonial occasion, but McReynolds refused to go, writing: "As you know, I am not always to be found when there is a Hebrew abroad. Therefore, my 'inability' to attend must not surprise you."[44] McReynolds refused to sit next to Brandeis (where he belonged on the basis of seniority) for the Court photograph in 1924. "The difficulty is with me and me alone," McReynolds wrote Taft. "I have absolutely refused to go through the bore of picture-taking again until there is a change in the Court, and maybe not even then."[45] Taft capitulated, and no photograph was taken that year.[16][46]

Once, when another colleague, Harlan Fiske Stone, remarked to him of an attorney's brief: "That was the dullest argument I ever heard in my life," McReynolds replied: "The only duller thing I can think of is to hear you read one of your opinions."[33]

McReynolds's rudeness was not confined to colleagues on the Court. Once, when called before the chairman of the Golf Committee at the Chevy Chase club after complaints were filed against him, McReynolds said: "I've been a member of this club a good many years, and no one around here has ever shown me any courtesy, so I don't intend to show any to anyone else." The indignant chairman replied: "Mr Justice, you wouldn't be a member of this club if it wasn't for your official position. The members of this club have put up with your discourtesy for years, merely because you are a member of the Supreme Court. But I'm telling you now that the next time there is a complaint against you, you'll be suspended from the privileges of the golf course."[47] Justices Pierce Butler and Willis Van Devanter transferred from the Chevy Chase club to Burning Tree because McReynolds "got disagreeable even beyond their endurance".[48]

When a female lawyer appeared in the courtroom, McReynolds would reportedly mutter: "I see the female is here again." He would often leave the bench when a woman lawyer rose to present a case.[34] He thought the wearing of wrist watches by men to be effeminate, and the use of red fingernail polish by women to be vulgar.[33]

He forbade smoking in his presence. He is said to have been responsible for the "No Smoking" signs in the Supreme Court building, inaugurated during his tenure.[49] He would announce to any Justice who attempted to smoke in Conference that "tobacco smoke is personally objectionable to me". Any who tried "were stopped at the threshold".[50]

McReynolds's long-suffering domestic help – black, and subject to the Justice's views on race relations – gave him a nickname. They called him "Pussywillow."[51]

However, he was reportedly "extremely charitable" to the pages who worked at the Court,[50] and had a great love of children.[2] For example, he gave very generous assistance and adopted thirty-three children who were victims of the German bombing of London in 1940, and left a sizable fortune to charity.[33][34] When Oliver Wendell Holmes's wife died, McReynolds broke down and wept at her funeral.[47] Holmes wrote in 1926: "Poor McReynolds is, I think, a man of feeling and of more secret kindliness than he would get credit for."[33] He would often entertain at his apartment, and even passed cigarettes to his guests on occasion.[50] He often invited people for brunch on Sunday mornings. According to William O. Douglas, "On these informal occasions in his own home he was the essence of hospitality and a very delightful companion".[52] Once, when riding to his office on a street car, a drunk got on board and fell out in the aisle. McReynolds picked him up, helped him back to his seat, and sat beside him until they reached the top of Capitol Hill, leaving him only after giving explicit instructions to the conductor.[53] And when due to absence of more senior justices it fell on him to preside in court, "he was the soul of courtesy, graciously greeting and raptly listening to the arguments by lawyers of both sexes".[34] The public Justice McReynolds was noted for his hospitality. He entertained frequently at the Willard Hotel with guest lists of 150 people, including his fellow justices, and at an annual eggnog party which was one of the social highlights of the Christmas season. Alice Roosevelt, one of many friends, requested the services of his cook, Mrs. Parker, for her wedding breakfast to Nicholas Longworth.[54]

Retirement and death

After a substantial hearing loss in 1925, he strongly intended to resign from the Court, and was only dissuaded by requests from many friends to continue, pronouncing him "one of the few who have courageously stood for the rights of property and of the citizen."[55] He assumed senior status on January 31, 1941, effectively resigning from the court. He lived at the Rochambeau apartment complex in Washington, D.C. from 1915 until Roosevelt requisitioned the Beaux Arts building in 1935 for his New Deal requirements. McReynolds found a new apartment at 2400 Sixteenth Street, where he lived until his death on August 24, 1946. McReynolds never married,[2][16] which places him in the company of four other justices in the Court's history.[upper-alpha 5]

Legacy

McReynolds was buried in the Elkton Cemetery in Elkton, Kentucky.[56] Elkton residents fondly remember Justice McReynolds, pointing out both his home and office "with great pride and respect".[57]

Knox wrote "... in 1946 he [McReynolds] died a very lonely death in a hospital – without a single friend or relative at his bedside. He was buried in Kentucky, but no member of the Court attended his funeral though one employee of the Court traveled to Kentucky for the services." In contrast, as the clerk noted, when McReynolds's aged African-American messenger, Harry Parker, died in 1953, his funeral was attended by five or six Justices, including the Chief Justice. McReynolds' brother, Robert, had visited him in the hospital shortly before his death. In his will, McReynolds requested "let there be no service in Washington"; however the U.S. Marshal for the Supreme Court traveled to Elkton for the funeral. The Christian Science Monitor hailed McReynolds in tribute as: '"the last and lone champion on the Supreme Bench battling the steady encroachment of Federal powers on State and individual rights ... standing these later years at the Pass of Thermopylae."[58]

McReynolds bequeathed his entire estate to charity.[2][33][34] Among these bequests were additional funds to Children's Hospital in Washington, which he had supported for years, adding a new elevator, $10,000 and the residue of his estate. His books and opinions were left to the Library of Congress, and $10,000 and his judicial robe to Vanderbilt University, where he had served for 30 years on the Board of Trust.[59]

Papers

McReynolds' papers are held at many libraries around the country, namely: mainly at the University of Virginia Law School in Charlottesville, Virginia;[60] Harvard University Law School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Felix Frankfurter papers; John Knox papers (1920–80), available at the University of Virginia and Northwestern University; University of Kentucky at Lexington, Kentucky, William Jennings Price (1851–1952) papers; University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library at Ann Arbor, Michigan, Frank Murphy papers; Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota Pierce Butler papers; Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville, Tennessee, Robert Boyte Crawford Howell papers; University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, Homer Stille Cummings papers.[61][62]

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Taft Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the White Court

Further reading

- James Clark McReynolds at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- "McReynolds, James Clark," Dictionary of American Biography.

- "McReynolds, James Clark," American National Biography.

- Biographical Dictionary of the Federal Judiciary. Detroit: Gale Research, 1976.

- Bibliography on James Clark McReynolds at 6th Circuit United States Court of Appeals.

- Bond, James Edward, 1992. I dissent: the legacy of Chief [sic] Justice James Clark McReynolds. Lanham, MD: George Mason University Press. Distributed by arrangement with University Pub. Associates (The designation "Chief Justice" in the title is an error.)

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L, eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Knox, John, 1984, "A Personal Recollection of Justice Cardozo", Supreme Court Historical Society Quarterly 6

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

Notes

- ↑ One block from the Todd County courthouse, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places Inventory.[4]

- ↑ See free silver.

- ↑ This is the title of the chapter dedicated to McReynolds in Pearson & Allen (1936).

- ↑ "[McReynolds] was a headache... He would not speak to Brandeis, was clearly anti-Semitic, and was a disruptive force."[30]

- ↑ See Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States.

References

- ↑ "James Clark McReynolds". Federal Judicial Center. 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hall (2005)

- ↑ Jones (1983)

- ↑ National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: McReynolds House. National Park Service, 1976-06, 3.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Smith, Megan (Summer 2006). "Supreme Court Associate Justice James Clark McReynolds (1862-1946): Principled Defender of the Federal Constitution" (PDF). The Upsilonian. Upsilon Sigma Phi. 17: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- 1 2 "James C. McReynolds". Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ↑ "United States vs. American Tobacco, 221 U.S. 106, syllabus". Justia.com. 1911. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ↑ "United States vs. American Tobacco, 221 U.S. 106 full text opinion". Justia.com. 1911. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "James Clark McReynolds, Attorney General". Department of Justice. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ↑ U.S. vs. American Tobacco Company, 221 U.S. 106. Argued January 3, 4, 5 6, 1910; re-argued January 6, 9, 11, 12, 1911.

- 1 2 Bush, Cornelia. "James Clark McReynolds". footnote.com. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Fox, John. "James Clark McReynolds". Capitalism and Conflict: Supreme Court History, Law, Power & Personality, Biographies of the Robes. Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.infoplease.com?ce6/people/A0831041.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 "James C. McReynolds". Oyez Project Official Supreme Court media. Chicago Kent College of Law. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ariens, Michael (2002–2005). "James Clark McReynolds". Michael Ariens website. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- 1 2 Bush (2010)

- ↑ Burner (1969), p. 2026

- 1 2 Lucas, Roy (2004). "The Forgotten Justice James Clark McReynolds & The Neglected First, Second & Fourteenth Amendments". Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ↑ Ball (2006), p. 89

- ↑ Letter from Taft to Horace Taft, December 26, 1924; quoted in Pringle (1939), p. 971

- ↑ Schlesinger (1960), p. 456

- ↑ Letter from Taft to Helen Taft Manning, June 11, 1923, quoted in Mason (1964), p. 215

- ↑ Bickel & Schmidt (1985), p. 413

- ↑ Warner (1959), p. 115

- ↑ Letter from Taft to R.A. Taft, October 26, 1922, quoted in Mason (1964), p. 217

- ↑ Letter from William Howard Taft to Helen Taft Manning, June 11, 1923; Mason (1964), pp. 215–216

- ↑ Letter from J.C. McReynolds to Taft, November 23, 1929, quoted in Mason (1964), p. 216

- ↑ Letter from William Howard Taft to R.A. Taft, February 1, 1925, quoted in Mason (1964), p. 216

- ↑ Taft, Charles P. Swindler, William F., ed. My Father the Chief Justice Yearbook 1977. The Supreme Court Historical Society. p. 8.

- ↑ Burner (1969)

- 1 2 Abraham (1999), pp. 133–135

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burner (1969), p. 2024

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Baker (1991), p. 465

- ↑ Hall (1992), p. 543

- ↑ Baker (1984), p. 370

- ↑ Quoted in Pearson & Allen (1936), p. 225

- 1 2 Pearson & Allen (1936), p. 225

- 1 2 Kaufman (1998), p. 480

- ↑ Kaufman (1998), p. 480, attributed to Paul A. Freund at a talk delivered before the Harvard Law School Forum, March 7, 1977, from Kaufman's notes.

- ↑ Atkinson (1999), p. 111

- ↑ Baker (1984), p. 357

- ↑ Abraham (2008), p. 140

- ↑ Letter from McReynolds to Taft, ca. February 1922, quoted in Mason (1964), pp. 216–217

- ↑ Letter from McReynolds to Taft, ca. March 1924, quoted in Mason (1964), p. 217

- ↑ Letter from Taft to McReynolds, March 28, 1924, quoted in Mason (1964), p. 217

- 1 2 Pearson & Allen (1936), p. 226

- ↑ Pearson & Allen (1936), p. 131

- ↑ Burner (1969), pp. 2023–2024

- 1 2 3 Douglas (1980), p. 13

- ↑ Knox (2002)

- ↑ Douglas (1980), p. 14

- ↑ Pearson & Allen (1936), pp. 226–227

- ↑ Bush (2010), p. 75

- ↑ Bush (2010), p. 110

- ↑ James Clark McReynolds at Find a Grave.

- ↑ Christensen, George A. (1983). "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices". Journal of the Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. at Wayback machine.

- ↑ Christian Science Monitor, August 27, 1946, p. 16.

- ↑ Bush (2010), p. 238

- ↑ "Inventory of the Papers of Justice James Clark McReynolds 1819-1967". Collection Number Mss 85-1, A Collection in The Arthur J. Morris Law Library, Special Collections. University of Virginia. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- ↑ Location of Papers, 6th Circuit United States Court of Appeals.

- ↑ Federal Judicial Center, James Clark McReynolds Resources.

Bibliography

- Abraham, Henry J. (1999). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Clinton. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9604-9.

- Abraham, Henry J. (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II (5th ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5894-6.

- Atkinson, David (1999). Leaving the Bench: Supreme Court Justices at the End. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1058-7.

- Baker, Leonard (1984). Brandeis and Frankfurter: A Dual Biography. New York, NY: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-015245-1.

- Ball, Howard (2006). Hugo L. Black: Cold Steel Warrior. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507814-4.

- Baker, Liva (1991). The Justice from Beacon Hill: the Life and Times of Oliver Wendell Holmes. New York, NY: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-016629-0.

- Bickel, Alexander C.; Schmidt, Benno C., Jr. (1985). "The Judiciary and Responsible Government 1910–21". History of the Supreme Court of the United States. 8. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Burner, David (1969). "James C. McReynolds". In Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court 1789-1969: Their Lives and Major Opinions. New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8352-0217-6.

- Bush, Ann McReynolds (2010). Executive Disorder: The Subversion of the United States Supreme Court, 1914–1940. Cornelia Wendell Bush. ISBN 9781453652640.

- Douglas, William O. (1980). The Court Years 1939–1975: The Autobiography of William O. Douglas. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 0-394-49240-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Hall, Kermit L. (2005). "McReynolds, James Clark". The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-641-99779-2.

- Jones, Calvin P. (1983). "Kentucky's irascible conservative: Supreme Court Justice James Clark McReynolds". Filson Club History Quarterly. 57: 20–30.

- Kaufman, Andrew L. (1998). Cardozo. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-09645-2.

- Knox, John (2002). The Forgotten Memoir of John Knox: a Year in the Life of a Supreme Court Clerk in FDR's Washington. Edited by Dennis J. Hutchinson & David J. Garrow. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-44862-6.

- Mason, Alpheus Thomas (1964). William Howard Taft: Chief Justice. London: Oldbourne.

- Pearson, Drew; Allen, Robert S. (1936). The Nine Old Men. New York, NY: Doubleday, Doran, and Company, Inc.

- Pringle, Henry F. (1939). The Life and Times of William Howard Taft: A Biography. 2. New York, NY: Farrack and Rinehart, Inc.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. (1960). The Politics of Upheaval: 1935–1936, the Age of Roosevelt. 3. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Warner, Hoyt Landon (1959). The Life of Mr. Justice Clarke. Cleveland, OH: Western Reserve University Press.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Clark McReynolds. |

- Biography, James Clark McReynolds at Federal Judicial Center.

- Supreme Court Historical Society, James C. McReynolds.

- Authorized Biography, James Clark McReynolds, Defender of the Constitution

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Wickersham |

United States Attorney General 1913–1914 |

Succeeded by Thomas Gregory |

| Preceded by Horace Lurton |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1914–1941 |

Succeeded by James Byrnes |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||