Jajce

| Jajce Јајце | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Top left:Pliva Waterfall, Top right:Panrama view eastern Marsala Tita area, from Jajca Fortress, Middle right:Jajca Fortress and ancient area, Bottom left:View of Sejh Mustafe area, Bottom right:Meadow Gate and Omer Bey's Native House | ||

| ||

| ||

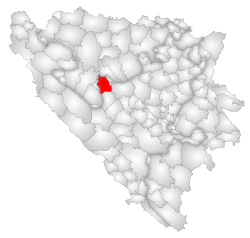

Jajce Location of Jajce in Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||

| Coordinates: 44°20′30″N 17°16′10″E / 44.34167°N 17.26944°ECoordinates: 44°20′30″N 17°16′10″E / 44.34167°N 17.26944°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Entity | Federation of BiH | |

| Canton | Central Bosnia | |

| Government | ||

| • Municipality president | Edin Hozan (SDA) | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 339 km2 (131 sq mi) | |

| Population (2013 census)[2] | ||

| • Total | 30,758 | |

| • Density | 91/km2 (240/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Area code(s) | +387 30 | |

| Website | http://www.opcina-jajce.ba | |

Jajce is a city and municipality located in the central part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the Bosanska Krajina region. It is part of the Central Bosnia Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity. It is on the crossroads between Banja Luka, Mrkonjić Grad and Donji Vakuf, on the confluence of the rivers Pliva and Vrbas.

History

Jajce was first built in the 14th century and served as the capital of the independent Kingdom of Bosnia during its time. The town has gates as fortifications, as well as a castle with walls which lead to the various gates around the town. About 10–20 kilometres from Jajce lies the Komotin Castle and town area which is older but smaller than Jajce. It is believed the town of Jajce was previously Komotin but was moved after the Black Death.

The first references to the name of Jajce in written sources is from the year 1396, but the fortress had already existed by then. Jajce was the residence of the last Bosnian king Stjepan Tomasevic; the Ottomans besieged the town and executed him, but held it only for six months, before the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus seized it at the siege of Jajce and established the Banovina of Jajce.[3]:36

Skenderbeg Mihajlović besieged Jajce in 1501, but without success because he was defeated by Ivaniš Korvin assisted by Zrinski, Frankopan, Karlović and Cubor.[4]

During this period, Queen Catherine restored the Saint Mary's Church in Jajce, today the oldest church in town. Eventually, in 1527, Jajce became the last Bosnian town to fall to Ottoman rule.[5] The town then lost its strategic importance, as the border moved further North. There are several churches and mosques built in different times during different rules, making Jajce a rather diverse town in this aspect.

Jajce passed with the rest of Bosnia and Herzegovina under the administration of Austria-Hungary in 1878. The Franciscan monastery of Saint Luke was completed in 1885.

From 1929-41, Jajce was part of the Vrbas Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. During the Second World War, Jajce gained importance as centre of a large swath of free territory, and on 29 November 1943 it hosted the second convention of the Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ). There, representatives from throughout Yugoslavia decided to establish a federal Yugoslavia in equality of its nations, and established that Bosnia and Herzegovina would be one of its constitutive Republics. Post-war economy of Jajce in socialist times was based on industry and tourism.[3]:36

At the beginning of the Bosnian War, Jajce was inhabited by people from all ethnic groups, and was situated at a junction between areas of Serb majority to the north, Bosnian Muslim majority areas to the south-east and Croatian majority areas to the south-west.

Bosnian war

At the end of April and the beginning of May 1992, almost all Serbs left the city and fled to territory under the Republika Srpska control. In the summer of 1992, the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) started heavy bombardment of the city; the town, that was defended by Croat (HVO) and Bosniak (ARBiH) forces with two separate command lines, fell to the superior Serbs forces on 29 October. Retreating forces where joined by a column of 30,000 to 40,000 civilian refugees, stretching 16 kilometres (10 miles) towards Travnik, under VRS sniping and shelling. Shrader defined it as "the largest and most wretched single exodus" of the Bosnian War.[6] Bosniak refugees re-settled in Central Bosnia, while Croats move out towards Croatia due to rising tensions. By November 1992 the pre-war population of Jajce had shrunk from 45,000 to just several thousand.[7]

In the following weeks, all of the mosques and Roman Catholic churches in Jajce were demolished as retribution for the HVO's destruction of the town's only Serbian Orthodox monastery (Crkva Uspenja Presvete Bogorodice) on 10–11 October. The VRS converted the town's Franciscan monastery into a prison and its archives, museum collections and artworks were looted; the monastery church was completely destroyed. By 1992, all religious buildings in Jajce had been destroyed, save for two mosques whose perilous positioning on a hilltop made them unsuitable for demolition.[8]

Jajce was recaptured together with Bosanski Petrovac in mid-September 1995 during Operation Mistral 2 by the Croatian Defence Council (HVO),[9] after VRS forces had evacuated the Serb population. Jajce became part of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina according to the Dayton Agreement. Even returning Bosniaks were at start blocked by a mob of Croats in early August 1996, which according to US diplomat Robert Gelbard was personally directed by Bosnian Croat war criminal Dario Kordic. Bosniak refugees could return peacefully only few weeks after, being followed by many more, and Dario Kordic surrendered and flew to the Hague, after US pressures over Zagreb.[10] A significant portion of Serb refugees settled in Brčko while the rest settled in Mrkonjić Grad, Šipovo, and Banja Luka.[11]

Economy and culture

The economy of the Jajce municipality is nowadays weak. UNESCO has started to renovate the historical parts of the city together with Kulturarv utan gränser (Cultural Heritage without Borders), a Swedish organisation. The main project of the company was to renovate the old traditional houses which symbolised the panoramic view of the city and the waterfall. As of 2006, most of the houses were rebuilt.

Tourism

Jajce was a popular tourist destination in Yugoslav times, mostly due to the historical importance of the AVNOJ session. Tourism has restarted, and its numbers (20-55,000 tourists in 2012-2013) are relevant in relation with the municipality's population (25,000). Tourists from across former Yugoslavia still make up most of tourism in Jajce, but middle-eastern tourists have also increased since the early 2000s; organised school trips also are a significant portion of touristic influx. Spring and autumn are the main tourist seasons.[3]:40

The town is famous for its beautiful waterfall where the Pliva River meets the river Vrbas. It was thirty meters high, but during the Bosnian war, the area was flooded and the waterfall is now 20 meters high. The flooding may have been due to an earthquake and/or attacks on the hydroelectric power plant further up the river.

Jajce is situated in the mountains, there is a beautiful countryside near the city, rivers such as the Vrbas and Pliva, lakes like Pliva lake, which is also a popular destination for the local people and some tourists. This lake is called Brana in the local parlance. Not far from Jajce there are mountains that are over two thousand meters high like Vlasic near the city of Travnik. Travelling through the mountain roads to the city may not sit well with some visitors, because the roads are in poor condition, but the scenery is picturesque.[12][13][14]

Demographics

In 1931 today's municipality of Jajce was part of the much bigger Jajce County (together with today's municipalities of Jezero, Dobretići and Šipovo).

| Ethnic Composition | |||||||||||||

| Year | Serb | % | Bosniaks | % | Croats | % | Yugoslavs | % | Others | % | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 24,176 | 49.84% | 14,205 | 29.28% | 10,080 | 20.78% | - | - | - | - | 48,510 | ||

| 1961 | 8,670 | 25.14% | 7,545 | 21.88% | 13,733 | 39.82% | 4,342 | 12.59% | 198 | 0.57 | 34,488 | ||

| 1971 | 8,132 | 23.23% | 14,001 | 40.00% | 12,376 | 35.35% | 208 | 0.59% | 285 | 0.83% | 35,002 | ||

| 1981 | 7,954 | 19.31% | 15,145 | 36.76% | 14,418 | 35.00% | 3,177 | 7.71% | 503 | 1.22% | 41,197 | ||

| 1991 | 8,663 | 19.24% | 17,380 | 38.61% | 15,811 | 35.13% | 2,496 | 5.54% | 657 | 1.48% | 45,007 [15] | ||

365 Serbs from Jajce are documented to have been killed in Jasenovac concentration camp during World War II.[16]

1991

In the town itself, there was 13,579 people, with distribution by ethnic groups:

- Bosnian Muslims - 5,277 (38.86%)

- Bosnian Serbs - 3,797 (27.96%)

- Yugoslavs - 2,217 (16.32%)

- Bosnian Croats - 1,899 (13.98%)

- others and unknown - 389 (2.88%)

1995

In accordance with the Dayton agreement, municipality borders were changed, and included some villages with the Bosnian Croat majority before the war (Mrkonjić Grad and Kneževo municipalities) and excluded some villages with the Bosnian Serb or Bosniak majority before the war.

Settlements

- Bare

- Barevo

- Bavar

- Biokovina

- Bistrica

- Borci

- Božikovac

- Bravnice

- Brvanci

- Bučići

- Bulići

- Carevo Polje

- Cvitović

- Čerkazovići

- Ćusine

- Divičani

- Dogani

- Donji Bešpelj

- Doribaba

- Drenov Do

- Dubrave

- Đumezlije

- Gornji Bešpelj

- Grabanta

- Grdovo

- Ipota

- Jajce

- Jezero

- Kamenice

- Karići

- Kasumi

- Klimenta

- Kokići

- Kovačevac

- Krezluk

- Kruščica

- Kuprešani

- Lendići

- Lučina

- Lupnica

- Ljoljići

- Magarovci

- Mile

- Peratovci

- Perućica

- Podlipci

- Podmilačje

- Prisoje

- Prudi

- Pšenik

- Rika

- Selište

- Seoci

- Smionica

- Stare Kuće

- Šerići

- Šibenica

- Vinac

- Vrbica

- Vukićevci

- Zastinje

- Zdaljevac

- Žaovine

Twin towns

-

Piacenza, Italy

Piacenza, Italy -

Hallsberg, Sweden

Hallsberg, Sweden -

Alaçatı, Turkey

Alaçatı, Turkey -

Ottensheim, Austria

Ottensheim, Austria -

Virovitica, Croatia

Virovitica, Croatia -

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina -

Tomislavgrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Tomislavgrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina

References

- ↑ "Osnovne informacije o kantonu". Služba za statistiku za područje Srednjobosanskog kantona u Travniku. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Estimation of the population of the Federation Bosnia and Herzegovina, june 30, 2007 (PDF), Federalni zavod za statistiku, 2007-06-30, retrieved 2007-10-11

- 1 2 3 The wider benefits of investment in cultural heritage: Case studies in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. Council of Europe, 2015

- ↑ Enciclopedia Croatica (in Croatian) (III ed.). Zagrem: Naklada Hrvatskog Izdavalačkog Bibliografskog Zavoda. 1942. p. 157. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ↑ Pinson, Mark (1996) [1993]. The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Historic Development from Middle Ages to the Dissolution of Yugoslavia (Second ed.). United States of America: President and Fellows of Harvard College. p. 11. ISBN 0-932885-12-8. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

[...] in Bosnia Jajce under Hungarian garrison actually held until 1527

- ↑ Shrader, Charles R. (2003). The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia: A Military History, 1992–1994. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-261-4., p.3

- ↑ Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973036-0., p.126

- ↑ Walesek, Helen (2013). "Destruction of the Cultural Heritage in Bosnia-Herzegovina: An Overview". In Walasek, Helen. Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage. London, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-40943-704-8. pp=82, 292

- ↑ Richard Holbrooke, To end a war, Random House 1998, p. 158

- ↑ Richard Holbrooke, To end a war, Random House 1998, p. 350

- ↑ A Tale of Two Cities: Return of Displaced Persons to Jajce and Travnik (PDF) (Report). International Crisis Group. 3 June 1998. pp. 2–7.

- ↑ Visit Jajce

- ↑ BiH Tourism

- ↑ Bradt Guide

- ↑ "Stanovništvo prema općinama po mjesnim zajednicama po nacionalnoj pripadnosti". Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina:Federal Bureau of statistics. 2006-03-17. Archived from the original on 2007-09-25. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ cp13.heritagewebdesign.com; accessed 16 May 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jajce. |

- Everything about Jajce(Bosnian)(Croatian)

- Image of Town and Waterfall

- Official Website(Bosnian)(Croatian)

- Tourism in Jajce(Bosnian)(English) (Italian)(German)

- Agency for Cultural, Historical and Natural Heritage and Development of Tourist Potential of Town Jajce(Bosnian)(Croatian)(English)

- Tragovima bosanskog kraljevstva - Tourist route for medieval Bosnia (English)

- Trail of the Bosnian Kingdom - Cultural Tourism in Jajce

- Jajce Tours by Sarajevo Funky Tours - Jajce Tours (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

.jpg)