Italian colonists in the Dodecanese

Italian colonists were settled in the Dodecanese Islands of the Aegean Sea in the 1930s by the Fascist Italian government of Benito Mussolini, Italy having been in occupation of the Islands since the Italian-Turkish War of 1911.

By 1940 the number of Italians settled in the Dodecanese was almost 8,000, concentrated mainly in Rhodes. In 1947, after the Second World War, the islands came into the possession of Greece: as a consequence most of the Italians were forced to emigrate and all of the Italian schools were closed. However, their architectural legacy is still evident, especially in Rhodes and Leros.

History

The Kingdom of Italy occupied the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean sea during the Italian-Turkish war of 1911. In the 1919 Venizelos-Tittoni Agreement, Italy promised to cede the overwhelmingly Greek-inhabited islands, except Rhodes, to Greece, but this treaty was never implemented due to the Greek catastrophe in Asia Minor. With the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, the Dodecanese was formally annexed by Italy, as the Possedimenti Italiani dell'Egeo.

In the 1930s, Mussolini embarked on a program of Italianization, hoping to make the island of Rhodes a modern transportation hub that would serve as a focal point for the spread of Italian culture in Greece and the Levant. The Fascist program did have some positive effects in its attempts to modernize the islands, resulting in the eradication of malaria, the construction of hospitals, aqueducts, a power plant to provide Rhodes' capital with electric lighting and the establishment of the Dodecanese Cadastre.

The main castle of the Knights of St. John was also rebuilt. The concrete-dominated architectural style blended in with the islands' picturesque scenery (and also reminded the inhabitants of Italian rule), but has consequently been largely demolished or remodeled, apart from the famous example of the Leros town of Lakki (founded by the Italians as Portolago), which remains a prime example of Italian Rationalism.

From 1923 to 1936 governor Mario Lago was able to integrate the Greek, Turkish and Ladino Jewish communities of the island of Rhodes with the Italian colonists. Lago's term of office constituted what might in retrospective be called the "Golden Period" of the Italian Dodecanese, with the economy booming and a relatively harmonious society.[1]

In the 1936 Italian census of the Dodecanese islands, the total population was 129,135, of which 7,015 were Italians. Nearly 80% of the Italian colonists lived in the island of Rhodes. Approximately 40,000 Italian soldiers and sailors were on military duty in the Dodecanese islands in 1940.

The appointment of Fascist quadrumvir Cesare Maria De Vecchi as governor of the Italian Aegean Islands in 1936 marked a turning point. De Vecchi promoted a more vigorous and forceful program of Italianization, which was only interrupted by Italy's entry in World War II in 1940.[2]

Indeed, he promoted the possible unification of the islands to Italy as part of the fascist ideal of an Imperial Italy.

During World War II, Italy joined the Axis Powers, and used the Dodecanese as a naval staging area for its invasion of Crete in 1940. After the surrender of Italy in September 1943, the islands briefly became a battleground between the Germans, British and the Italians (the Dodecanese Campaign). The Germans prevailed, and although they were driven out of mainland Greece in 1944, the Dodecanese remained occupied until the end of the war in 1945, during which time nearly the entire Jewish population of 6,000 was deported and killed. Only 1200 of these Ladino-speaking Jews survived, thanks to their lucky escape to the nearby coast of Turkey with some help from the Italian colonists of Rhodes. In the Treaty of Paris in 1947, the islands were ceded to Greece.

Disappearance of the Italian community

For the nearly 8,000 Italian colonists, after the Italian defeat in World War II, started a process of return to Italy and successive disappearance. The Dodecanese officially passed from Italy to Greece in 1947, and in that year all the Italian schools were closed. Some of the Italian colonists remained in Rhodes and were quickly assimilated. Actually only a few dozen old colonists remain, but the influence of their legacy is evident in the relative diffusion of the Italian language mainly in Rhodes and Leros.

Architectural legacy

The citadel of Rhodes city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site thanks in great part to the large-scale restoration work carried out by the Italian authorities. The Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes formed the centerpiece of this project, after being largely destroyed by an ammunition explosion in 1856.

In the 1920s, the Italians demolished the houses that were built in and around the city walls during the Ottoman period. They also turned the Jewish and Ottoman cemeteries into a green zone surrounding the Medieval Town. The Italians preserved what was left from the Knights' period, and destroyed all other Ottoman buildings that weren't of importance. Furthermore, in those years an "Institute for the study of the History and Culture of the Dodecanese region" was established, and major infrastructure work was done to modernize Rhodes. Buildings like the Aquarium were built, mainly in art deco style.

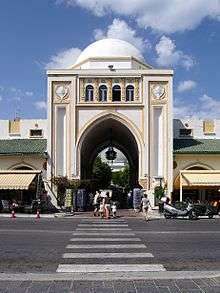

Indeed, in all the Dodecanese islands remains a huge architectural legacy[3] from the Italian colonists. Here are some examples:

- The Grande Albergo delle Rose (now "Casino Rodos") built by Florestano Di Fausto and Michele Platania in 1927, with a mix of Arab, Byzantine and Venetian styles.

- The Casa del Fascio of Rhodes, built in 1939 in typical fascist style. It serves now as the City Hall.

- The Catholic church of San Giovanni, built in 1925 by Rodolfo Petracco, as a reconstruction of the medieval cathedral church of the Knights of St. John.

- The Teatro Puccini of the city of Rhodes, now called "National Theater", built in 1937 with 1,200 seats.

- The Palazzo del Governatore in downtown Rhodes, built in 1927 in Venetian style. It now houses the offices of the Prefecture of the Dodecanese.

- The Villaggio rurale San Benedetto, now Kolymbia village, built in 1938 as a planned model village with all modern services.

- The Community of Portolago (now Lakki) in the island of Leros, built in 1938 in typical Italian Deco style.

Notes

- ↑ "Gli anni dorati 1923 - 1936" (in Italian). Dodecaneso.

- ↑ Dubin, Marc Stephen (2002). Rough Guide to the Dodecanese & East Aegean islands. Rough Guides. p. 436. ISBN 978-1-85828-883-3.

- ↑ "Architettura" (in Italian). Dodecaneso.

Bibliography

- Antonicelli, Franco. Trent'anni di storia italiana 1915 - 1945. Mondadori. Torino, 1961.

- Clogg, Richard. A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 2002.

- Doumanis, Nicholas. Italians as "Good" Colonizers: Speaking Subalterns and the Politics of Memory in the Dodecanese, in Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Mia Fuller, Italian Colonialism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2005. ISBN 0-312-23649-2.

- Manicone, Gino. Italiani in Egeo La Monastica. Casamari, 1989.

- Pignataro, Luca. Le Isole Italiane dell'Egeo dall'8 settembre 1943 al termine della seconda guerra mondiale in "Clio. Rivista internazionale di studi storici", 3 (2001)

- Pignataro, Luca. Il tramonto del Dodecaneso italiano 1945-1950 in "Clio. Rivista internazionale di studi storici", 4 (2001)

- Pignataro, Luca Ombre sul Dodecaneso italiano in "Nuova Storia Contemporanea" 3 (2008)

- Pignataro, Luca Il Dodecaneso italiano, con appendice fotografica, in "Nuova Storia Contemporanea" 2 (2010)

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fascist architecture in Rhodes. |

- Website about the history of Italian Dodecanese (Italian)

- Photos of the Palace of the Grand Master (of the Knights of St. John) in the city of Rhodes, rebuilt by the Italians in the 1930s