István Tisza

| Count István Tisza de Borosjenő et Szeged | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Hungary | |

|

In office 3 November 1903 – 18 June 1905 | |

| Monarch | Francis Joseph I |

| Preceded by | Károly Khuen-Héderváry |

| Succeeded by | Géza Fejérváry |

|

In office 10 June 1913 – 15 June 1917 | |

| Monarch |

Francis Joseph I Charles IV |

| Preceded by | László Lukács |

| Succeeded by | Móric Esterházy |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

22 April 1861 Pest, Hungary |

| Died |

31 October 1918 (aged 57) Budapest, Hungary |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Political party |

Liberal Party National Party of Work |

| Religion | Calvinism |

Count István Tisza de Borosjenő et Szeged (archaically English: Stephen Tisza; 22 April 1861 – 31 October 1918) was a Hungarian politician, prime minister, political scientist and member of Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The prominent event in his life was Austria-Hungary's entry into the First World War when he was prime minister for the second time. He was later assassinated during the Chrysanthemum Revolution on 31 October 1918 - the same day that Hungary terminated its political union with Austria. Tisza supported the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary and was representative of the then liberal-conservative consent.

He had been a Member of Parliament since 1887 and had had abundant opportunities to see how the unyielding temper of the Emperor on the one hand, and the revolutionary spirit of the extremists on the other, were leading to a complete impasse. He himself supported the Compromise of 1867. A social reactionary to the end, Tisza stubbornly opposed on principle the break-up of the large landed estates as well as even the most modest reform proposals that would have granted the suffrage to soldiers fighting at the front[1] (before 1918 only 10% of the Hungarian population could vote and hold office). However, in economic affairs, he tended to be a modernizer who encouraged and supported industrialization and, in that respect, he was an opponent of anti-Semitism, which he feared could jeopardize Hungary's economic development.

Tisza's role model was Otto von Bismarck. As an economist he followed the concepts of English historical school of economics, as lawyer and political scientist, Tisza favored the societal and political development of England, which he considered as "ideal way of development".[2]

Early life and education

István Tisza was the son of Kálmán Tisza de Borosjenő, prime minister of Hungary between 1875–1890 from the Liberal Party. The Tiszas were originally a Calvinist untitled lower nobility (regarded as equivalent to the British gentry). His mother was a southern German aristocrat Ilona Degenfeld-Schomburg, from Baden-Württemberg (born: Helene Johanna Josepha Mathilde Gräfin von Degenfeld-Schonburg).

The young Stephen raised in a puritanical and authoritarian Calvinist environment with high expectations. Stephen has studied at home until the age of twelve, then he entered the Calvinist Gymnasium (a college-preparatory school) of Debrecen. Tisza took legal studies in Budapest, international law in Heidelberg University, economics in Humboldt University of Berlin, where he received PHD, and political science in Oxford University, where he received a doctorate in political science.

Political career

Tisza as member of the parliament

He then took care of the family land at Bihar County and Geszt for five years. He won his first parliamentary electoral mandate in 1886 with the Liberal Party in Vízakna (Now: Ocna Sibiului, Romania), a Transylvanian electoral district, and he represented the district until 1892. He won his second seat in 1892 as representative of Újbánya district (Now: Nová Baňa, Slovakia). In 1896 he won the seat of Ugra district (Now: Ungra, Romania) and he became also a member of the economic committee of Hungarian parliament, where he plunged himself into the macroeconomic discussions.

In the 1890s he served a number of sinecures which provided extraordinary income, a common situation among prestigious European politicians of the time. He was the president of the Hungarian Industrial and Commercial Bank (Magyar Ipar- és Kereskedelmi Bank) and was a member of the boards of numerous joint-stock companies and industrial enterprises. Despite the financial crisis of the 1890s, under his control many of these enterprises became the fastest emerging companies of the realm, some of them became unavoidable enterprises in their own sectors. His instructions and rule transformed the mediocre Hungarian Industrial and Commercial Bank into the largest Bank of Hungary within a decade.

His uncle, the childless Lajos Tisza received the title of Count from Emperor Franz Joseph in 1897. However, Lajos Tisza conferred his new title on his nephew Stephen with the consent of the Monarch.

Prime minister for first time, 1903–1905

Target of Leftist and socialist circles

In this period he managed to get the remains of Francis II Rákóczi repatriated from Turkey and interred in the cathedral of Kassa, today Košice. The Parliament approved the increase of conscriptees. As the minister of Internal Affairs he aggressively silenced the railway workers strike in 1904. The organisers were arrested and the strikers were recruited into the army. The police crushed a Socialist gathering for peasants in Bihar, leaving 33 dead and several hundred wounded.

Target of anti-Semite circles

Tisza often used his influence in parliament to grant titles to wealthy Jewish families, especially successful industrialists and bankers, and set them and their success as an example for the people. Many families of young middle class were Jews or baptized Jews. Tisza often gathered influential men of Jewish extraction to advise him. He even offered many positions in his cabinet to Jews. His first appointment was Samu Hazai. Two years later he picked János Teleszky as minister of finance. The third Jewish member of his cabinet was János Harkányi, minister of trade. Tisza appointed Samu Hazai as Minister of War during his second premiere. They all served for the duration of Tisza’s seven years in office. His philosemitic political attitude made him a target of anti-Semite politicians and political circles.

Target of radical nationalists

During the era, only 54.5% (1910 census[3]) of the population of kingdom of Hungary considered themselves as Hungarians. Tisza's party (The Liberal Party of Hungary) urgently needed the support of minorities to maintain the majority of the party in the Hungarian parliament. The liberal party was the most popular political force in the electoral districts where the ethnic minorities represented the local majority. However his main political opponents (The nationalist Party of Independence and '48 and Catholic People's Party) could collect mandates only from the Hungarian majority electoral districts.[4]

"Election by handkerchief" and electoral defeat in 1905

He passed a modification to the rules of the House of Parliament on 18 November 1904 to crush the obstruction of the opposition. In earlier era, the members of the parliament had unrestricted time to give speech or talk in the parliament.

From the first his ministry was exposed to the most unscrupulous opposition, exacerbated by the new and stringent rules of procedure which Tisza felt it his duty to introduce if any business were to be done. The motion for their introduction was made by the deputy Gábor Daniel, supported by the premier, and after scenes of unheard-of obstruction and violence (November 16-18) the speaker, in the midst of an ear-splitting tumult, declared that the new regulations had been adopted by the house, and produced a royal message suspending the session. But the Andrássy group, immediately afterwards, separated from the Liberal Party, and the rest of the year the Opposition made the legislation impossible. By January 1905 the situation had become ex lex or anarchical. Tisza stoutly stood by his rules, on the ground that this was a case in which the form must be sacrificed to the substance of parliamentary government.[5]

Dezső Perczel, the President of the House, called for immediate voting on the modification. It is not clear what exactly happened, but some sources say that the Speaker of the House of Parliament waved a handkerchief, signalling for the governing party to vote "yes"; this act later became known as the "election by handkerchief", which became a large scandal and, as a consequence, Kálmán Széll and Gyula Andrássy left the Liberal Party and the opposition unified into the "Federal Opposition". The political powers polarised and in new elections the 30 years of governing by the Liberal Party was ended, with the side effect that the party was dissolved.

National Party of Work, electoral victory in 1910

After that defeat Tisza only took part in the operations of the House of Parliament, staying away from political struggles. However, the governing Independence and '48 Party was unable to withhold positions to protect the interests of Hungary so it resigned on 25 April 1909. On 19 February 1910, Tisza established the National Party of Work (Nemzeti Munkapárt) which subsequently won the election of 1910. He did not desire to form a government, primarily due to his conflict with Franz Ferdinand who sought to centralise the Habsburg Empire with universal suffrage. Tisza opposed this initiative, as he believed that this would lead to the weakening of the Magyar supremacy over ethnic minorities in Hungary. In addition, he claimed "demagogues would manipulate peasants with the majority of the votes to put in power such groups whose aims are against democracy, supported by the urban intellectuals"[6] (i.e. Communists). Tisza was supported by Franz Josef, but he feared a repeat of the faults of his first prime ministry and thus called for Károly Khuen-Héderváry to form the new government.

Act of Protection

As Speaker of the House of Representatives from 22 May 1912 to 12 June 1913 Tisza supported the reform of the common Austro-Hungarian army to enhance the military power of the dual monarchy. The Hungarian side was fighting for more Hungarian interests (i.e. use of the Magyar language in the army). The Socialists strongly opposed his acts and organised a rebellion on 22 May 1912 (Blood-Red Thursday), calling for Tisza to resign as President of the House and calling for universal suffrage.

Tisza tried to solve the question of ethnic minorities based on a clerical approach (like the representation of Orthodox and Greek Catholic Church in The Upper House of the parliament).

He was convinced that the challenging foreign situation called for military preparation and he strongly pushed against opposition obstruction. He did not allow the opposition to speak up regarding rules of House of Parliament. Referring to an act of 1848, he called for the police force to force out numerous opposition representatives. He managed to pass the Act of Protection, resulting in the removal of some members of the opposition party.

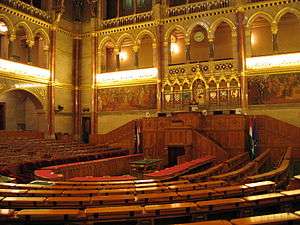

As a result, Gyula Kovács, an opposition party representative, tried to assassinate Tisza in the Parliament Building on 7 June 1912. His shots missed and the marks are still visible in the Hungarian Parliament Building to this day. With his last shot Kovács shot himself, but he survived. Tisza then continued the session.

Prime minister for second time, 1913–1917

Tisza became prime minister again on 7 June 1913. During this period of international insecurity, he wanted to solidify the government.

Freedom of the press

Inspired by the Western European model, Tisza's cabinet introduced first time the legal category of defamation, libel and "scare-mongering" in the history of Hungarian journalism, thus the press became actionable before the courts. Journalists and newspapers had to pay compensations for the victims of defamation and libel. Despite these institutions worked well in Western Europe and in the United States, the contemporary Hungarian newspapers and journalists considered it as the violation of the Freedom of Speech and the Freedom of Press.

Foreign policy and the Great War

A few days before the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, which resulted in World War I, Tisza supported a strong stand against Serbia. However, after the assassination he was against going to war against Serbia, a rare view in Austria-Hungary. He knew the army's strength, and he was afraid that with the increase of more Slavic territories the equilibrium inside the monarchy would be upset. Moreover, he was afraid that Romania would attack Transylvania.[7] The loss of the alliance with the German Empire would have meant the end of Austria-Hungary as a Great Power, so he gave in and supported the war. He then became a relentless supporter of the war until its end.

Tisza believed Romania to be an enemy from the beginning. He was afraid that if Romania attacked Hungary then the Romanians in Transylvania would revolt against Hungary. In the end, 40,000 soldiers were moved to protect Transylvania.

During the war, the reformists became more and more powerful, but he continued to oppose them. He opposed even the ideas of the new king, Karl I, and so he resigned on 23 May 1917. However, he retained great political influence, and was able to delay the enactment of universal suffrage.

Towards the end of the war, he wanted to convince the Serbs and Bosnians to achieve autonomy within Austria-Hungary. As a homo regius (“king's man”), he went to Sarajevo to attempt this, but without success.

His judgement from abroad during and after the war

It is clear that after the outbreak of World War I, all opposing sides pointed to the other side as the party guilty of initiating the greater war. Interestingly, the British newspaper “New Europe” printed a comment that Hungary was the only responsible party for the war, “where Hungary′s responsibility is greater than Austria′s” and that Tisza was the militaristic politician who dragged all sides into war. As a consequence the “Little Entente” took this view and pushed to punish Hungary at the end of the war. Later, the propaganda of these nations augmented and even invented Tisza's guilt, claiming that he took pains to point out in a report of 8 July that "there should at any rate be no question of the annihilation or annexation of Serbia, and that if Serbia gave way, Austria-Hungary must be content." According to recent findings these accusations are without merit.

The accusations are rooted in the common belief that Tisza carried out a policy of forced Magyarization towards the ethnic minorities in Hungary. His minority policy was (directly or indirectly) often confused with his radical nationalist political opponents (like the The Party of Independence and '48.

His view on the war

Tisza opposed the expansion of the empire on the Balkan (see Bosnian crisis in 1908), because "the Dual Monarchy already had too many Slavs", which would further threaten the integrity of the Dual Monarchy.[8]

In March 1914, Tisza wrote a memorandum to Emperor Francis Joseph. His letter had strongly apocalyptic predictive and embittered tone. He used exactly the hitherto unknown "Weltkrieg" (means World War) phrase in his letter. "It is my firm conviction that Germany's two neighbors [Russia and France] are carefully proceeding with military preparations, but will not start the war so long as they have not attained a grouping of the Balkan states against us that confronts the monarchy with an attack from three sides and pins down the majority of our forces on our eastern and southern front."[9]

On the day of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Tisza immediately traveled to Vienna where he met Minister of Foreign Affairs Count Berchtold and Army Commander Conrad von Hötzendorf. They proposed to solve the dispute with arms, attacking Serbia. Tisza proposed to give the government of Serbia time to take a stand as to whether it was involved in the organisation of the murder and proposed a peaceful resolution, arguing that the international situation would settle soon. Returning to Budapest, he wrote to Franz Joseph saying he would not take any responsibility for the armed conflict because there was no proof that Serbia had plotted the assassination. Tisza opposed a war with Serbia, stating (correctly, as it turned out) that any war with the Serbs was bound to trigger a war with Russia and hence a general European war.[10] He thought that even a successful Austro-Hungarian war would be disastrous for the integrity of Kingdom of Hungary, where Hungary would be the next victim of Austrian politics. After a successful war against Serbia, Tisza adumbrated a possible Austrian military attack against Kingdom of Hungary, where the Austrians want to break up the territory of Hungary.[11] He did not trust in the Italian alliance, due to the political aftermath of the Second Italian War of Independence. He felt the threat of Romania and Bulgaria after the Balkan wars and was afraid of Romanian attack from the east. He was also not sure about the stand of the Germans. Germany's stand was of ultimate importance due to the security of the state.

During a conversation between Franz Joseph and Conrad von Hötzendorf, Conrad asked, "If Germany's reply is that they are on our side, do we engage in war with Serbia?" The emperor replied, "Then yes", "But what if they reply differently?", "Then the Monarchy will be alone".

Kaiser Wilhelm II supported the war, promised to neutralize a Romanian attack, and put pressure on Sofia. After this, Tisza still sought a peaceful solution, but most of all he wanted to wait for the result of the official examination into the assassination. The only proposal of Tisza, which was accepted, was that the Monarchy should not annihilate Serbia completely in order to avoid Russian support for Serbia. The council finally addressed an ultimatum to the Serbian government and immediately started the mobilisation of troops.

After sending the ultimatum, his view changed. The ultimatum was obsolete within 48 hours, so Tisza wrote: "it was a difficult decision to take a stand to propose war, but now I am firmly convinced of its necessity"[12] He was, however, still opposed to the annexation of Serbia to the Monarchy, but failed. On 4 August 1914 Russia, Germany, Britain and France also entered the war, enlarging it to a world war.

Tisza did not resign from the Prime Ministry, as he thought this was the best way he could represent Hungarian interests inside Austria-Hungary, as he had connections in Vienna. Moreover, his resignation would have sent a message of weakness to the Entente at the outbreak of war.

His initial opposition to the conflict, only became public after the end of World War 1, on 17 October 1918, when he spoke in the Parliament. From this speech, the only thing which was remembered is when he said "We (Hungarians) have lost this war!". He said, "the Monarchy and the Hungarian nation was longing for peace all the way until there were some series of proofs found which we found that the enemy was systematically trying to humiliate and destroy us as soon as possible (...) As we have found proofs that the Serbian government took part in organising the assassination, we could not do but to address an ultimatum to Serbia ... where we fixed that the war is preventive."

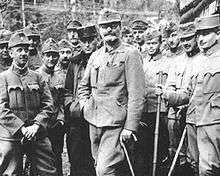

The struggle of a WW1 political leader in the trenches

The 57 years old Tisza joined to the 2nd Hussar Regiment of Hungary - which served on the Italian front - as a hussar colonel, and personally led his hussar units during the attacks.

Tisza at the front: "Tisza already felt the not too friendly atmosphere surrounding him at the first days of his joining up to the regiment and at first he tried to ease the general mood by informal behavior. (...) He has made an effort from the beginning to use an informal tone both with the staff of officers and -of course within the limits of the service regulations- with the rank and file. To better get to know each other with his fellow officers, every day he invited some young officers to his table, this way he tried to establish better personal relations with his environment. The troops had slowly started to recognize him as "tough to the upwards and humane to the downwards" kind of a commander. He distributed his tobacco provisions among the officers and he used his commander pay to improve the catering of the troops, and these of course left a good impression on everybody. Tisza's paternalistic attitude towards his subordinates also manifested itself in civil law cases: he helped with his personal influence in getting done of those petitions what he considered fair, he interceded with notaries, judges, alispáns (deputy-lieutenants) for advancing the home affairs of his men, due to this both the officers and the troops more and more came to like and embrace him. Tisza himself also felt that the front service had been quite useful and productive since on the one hand he could personally experience the dangers of the battleground an on the other hand-at least he was thinking that way and there is a lot of truth in it-he could truly become familiar with the real nature of the simple, peasant origin soldiers. He wrote about it in this way in a letter to Archduke Joseph: «I’ve got to truly know the ordinary/common people now. This is the most extraordinary race of the world that can only be loved and respected. How unfortunate that the political intelligentia doesn’t do anything else, just corrupts this great and God-blessed people.«” [13]

Assassination attempts against him

For many, he was the representative of the war policy in the Monarchy, so he was an assassination target. The fourth assassination attempt against him was successful.

The first attempt was made in the Hungarian parliament in 1912 by Gyula Kovács, an opposition politician. He shot two bullets, but missed Tisza. Kovács was arrested by the police, but he was acquitted by the court, the justification was "temporary insanity".

The second was made by a soldier when Tisza was returning from the front line during the war. The bullet missed him.

The third attempt came on 16 October 1918 when János Lékai, a member of the society Galilei-circle and an anti-military group led by Ottó Korvin, tried to kill Tisza while he was leaving the Hungarian Parliament, but the revolver malfunctioned and Tisza managed to flee.[14] The assassin was sent to prison but was released after 15 days during the Chrysanthemum Revolution.

The fourth and successful attempt came on 31 October 1918, when soldiers broke into his home, the Roheim villa in Budapest (Hermina út 35.) in front of his wife. Mihály Károlyi's government initiated an investigation but the killers were not found. However, the family members identified the killers in the trials. In the trial that followed the fall of the Communist regime and ended on 6 October 1921, Judge István Gadó established the guilt of Pál Kéri, who was exchanged with the Soviet Union; József Pogány, aka John Pepper, who fled to Vienna, then Moscow and the USA; István Dobó; Tivadar Horváth Sanovics, who also fled; Sándor Hüttner, who died in a prison hospital in 1923; and Tibor Sztanykovszky, who was the only one to serve his 18-year sentence, being released in 1938.

Sigmund Freud, Austrian neurologist – who knew the two politicians personally, wrote about the assassination of István Tisza and the appointment of Mihály Károlyi as new prime minister of Hungary:

I was certainly no adherent of the ancien régime, but it seems doubtful to me whether it is a sign of political shrewdness to beat to death the smartest of the many counts [Count István Tisza] and to make the stupidest one [Count Mihály Károlyi] president.[15]

Further reading about his political views

The detailed political views of Tisza about socialism atheism and class struggle, about parliamentarism and suffrage, about freedom of the press, about the question of nationality, about the land question, and about the Dual Monarchy and the world war: (by prof. Zoltán Maruzsa, Political scientist, ELTE University): http://tiszaistvan.hu/index.php/english

Notes

- ↑ Robert A. Kann, A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918, University of California Press, 1974, p. 494-495.

- ↑ Zoltán Maruzsa, Political scientist, ELTE University: "The standpoint of the Tisza István Friends Society concerning the historical figure of Count István Tisza". tiszaistvan.hu. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 1910. évi népszámlálás adatai. (Magyar Statisztikai Közlemények, Budapest, 1912. pp 30–33)

- ↑ See: Zoltán Maruzsa

- ↑ "Stephen Tisza" in the Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. 1911., VOLUME: XXVI, page:1017

- ↑ A magyar jobboldali hagyomány (Hungarian Right-Wing Heritage, 1900–1948. Edited by Ignác Romcsics, Osiris, 2009. pp. 65.

- ↑ Köpeczy-Makkai-Mócsy-Szász: History of Transylvania

- ↑ William Jannen: Lions of July: Prelude to War, 1914 - PAGE:456

- ↑ David G. Herrmann: The Arming of Europe and the Making of the First World War - PAGE: 211 , Princeton University Press, (1997) ISBN 9780691015958

- ↑ Fischer, Fritz: Germany’s Aims in the First World War, New York, W.W. Norton, 1967, ISBN 978-0-393-09798-6 (PAGE: 52)

- ↑ Duffy, Michael. "Who's Who - Count Istvan Tisza de Boros-Jeno". firstworldwar.com.

- ↑ Tschirschky's report to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 14 July 1914

- ↑ Peter Strausz: (Hungarian) "István Tisza and the Second Hussar Regiment"

- ↑ András Siklós. Revolution in Hungary and the Dissolution of the Multinational State. 1918. Studia Historica. Vol. 189. Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Budapest, 1988; p.32-33

- ↑ Sigmund Freud; Sándor Ferenczi; Eva Brabant; Ernst Falzeder; Patrizia Giampieri-Deutsch (1993). " The Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 2: 1914-1919. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674174191.

References

- Deák, Istvan "The Decline and Fall of Habsburg Hungary, 1914–18" pages 10–30 from Hungary in Revolution edited by Ivan Volgyes Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971.

- Menczer, Béla "Bela Kun and the Hungarian Revolution of 1919" pages 299–309 from History Today Volume XIX, Issue #5, May 1969, History Today Inc: London.

- Vermes, Gábor "The October Revolution In Hungary" pages 31–60 from Hungary in Revolution edited by Ivan Volgyes Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971.

- "Tisza István Friends Society".

External links

- Works by or about István Tisza at Internet Archive

-

Wertheimer, Eduard von (1922). "Tisza, Stephen". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).

Wertheimer, Eduard von (1922). "Tisza, Stephen". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). -

Media related to István Tisza at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to István Tisza at Wikimedia Commons

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Károly Khuen-Héderváry |

Prime Minister of Hungary 1903–1905 |

Succeeded by Géza Fejérváry |

| Minister of the Interior 1903–1905 |

Succeeded by József Kristóffy | |

| Minister besides the King 1903–1904 |

Succeeded by Károly Khuen-Héderváry | |

| Preceded by Lajos Návay |

Speaker of the House of Representatives 1912–1913 |

Succeeded by Pál Beőthy |

| Preceded by László Lukács |

Prime Minister of Hungary 1913–1917 |

Succeeded by Móric Esterházy |

| Preceded by Gejza Josipović |

Minister of Croatian Affairs Acting 1913 |

Succeeded by Teodor Pejačević |

| Preceded by Teodor Pejačević |

Minister of Croatian Affairs Acting 1914–1916 |

Succeeded by Imre Hideghéthy |

| Preceded by István Burián |

Minister besides the King Acting 1915 |

Succeeded by Ervin Roszner |