Iddin-Dagan

| Iddin-Dagān | |

|---|---|

| King of Isin | |

| |

| Reign | ca. 1910 BC – 1890 BC |

| Predecessor | Šu-ilišu |

| Successor | Išme-Dagān |

| House | 1st Dynasty of Isin |

Iddin-Dagān, inscribed di-din dda-gan, ca. 1910 BC – 1890 BC (short chronology) or ca. 1975-1954 BC (middle chronology), was the 3rd king of the 1st dynasty of Isin, succeeding his father, Šu-ilišu, and reigned 21 years according to the Sumerian King List.[i 2] He is best known for his participation in the sacred marriage rite and the risqué hymn that describes it.[1]

Biography

His titles included: mighty king, king of Isin (sometimes king of Ur), king of the land of Sumer and Akkad.[nb 1] The first year name recorded on a receipt for flour and dates[i 3] reads: “Year Iddin-Dagān (was) king and (his) daughter Matum-Niatum (“the land which belongs to us”) was taken in marriage by the king of Anshan.”[nb 2][2] Vallat suggests it was to Imazu, son of Kindattu, who was the groom, as he is described as king of Anshan in a seal inscription, although elsewhere unattested. Kindattu, possibly the 6th king of the region of Shimashki,[i 4] had been driven from Ur by Išbi-Erra,[i 5] the founder of the dynasty of Isin, but relations had apparently thawed sufficiently for Tan-Ruhurarter, the 8th king to wed the daughter of Bilalama, the ensi of Eshnunna.[3]

There is only one contemporary monumental text extant for this king and another two known from later copies. A fragment of a stone statue[i 6] has a votive inscription which invokes Ninisina and Damu to curse those who foster evil intent against it. Two later clay tablet copies[i 7] of an inscription recording an unspecified object fashioned for the god Nanna were found by Leonard Woolley in a scribal school house in Ur. A tablet[i 8] from the Enunmaḫ at Ur dated to the 14th year of Gungunum, (ca, 1868 BC to 1841 BC) of Larsa, after his conquest of the city, bears the seal impression of a servant of his. A tablet[i 9] describes Iddin-Dagān’s fashioning of two copper festival statues for Ninlil, which were not delivered to Nippur until 117 years later by Enlil-bāni.[4] Belles-lettres preserve the correspondence from Iddin-Dagān to his general Sîn-illat about Kakkulātum and the state of his troops, and from his general describing an ambush by the Martu (Amorites).

The continued fecundity of the land was ensured by the annual performance of the sacred marriage ritual in which the king impersonated Dumuzi-Ama-ušumgal-ana and a priestess substituted for the part of Inanna. According to the šir-namursaḡa, the hymn composed describing it in ten sections (Kiruḡu), this ceremony seems to have entailed the procession of male prostitutes, wise women, drummers, priestesses and priests bloodletting with swords, to the accompaniment of music, followed by offerings and sacrifices for the goddess Inanna, or Ninegala. The ceremony reached its climax with the assembly of the “black-headed people” around a dais specially erected for the occasion when the king and priestess copulated to gawking onlookers[5] and is described thus:

She bathes (her) loins for the king. She bathes (her) loins for Iddin-Dagān. Holy Inanna bathes with soap, and sprinkles the floor with aromatic resin. The king then approached (her) loins with head raised high. Iddin-Dagān approached (her) loins with head raised high. Ama-ušumgal-ana lies down beside her and {caresses her holy thighs} (says:) "O my holy thighs! O my holy Inanna!." After the lady has made him rejoice with her holy thighs on the bed, after holy Inanna has made him rejoice with her holy thighs on the bed, she relaxes (?) with him on her bed: "Iddin-Dagān, you are indeed my beloved!"[6]— šir-namursaḡa to Inanna for Iddin-Dagān, 9th Kiruḡu

There are four extant hymns addressed to this monarch, which, apart from the Sacred Marriage Hymn, include a praise poem to the king, a war song and a dedicatory prayer.

Inscriptions

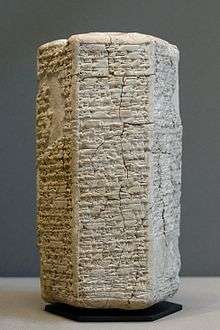

- ↑ Prism AO 8864, Louvre.

- ↑ Sumerian King List extant in 16 copies.

- ↑ Tablet UM 55-21-102, University Museum, Philadelphia.

- ↑ Dynastic list of the kings of Awan and Simashki, Sb 17729 in the Louvre.

- ↑ Išbi-Erra and Kindattu, tablets N 1740 + CBS 14051.

- ↑ MM 1974.26 Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm.

- ↑ Tablets IM 85467 and IM 85466, National Museum of Iraq.

- ↑ Excavation number U 2682.

- ↑ Tablet UM L-29-578, University Museum Philadelphia.

Notes

- ↑ lugal-kala-ga, lugal-i-si-in-KI-ga (lugal-KI-úri-ma), lugal-KI-en-gi-KI-uri-ke4.

- ↑ mu dI-dan dDa-gan lugal-e [Ma]-tum-ni-a-tum [dumu-mí]-a-ni lugal An-ša-an(a)[ki] ba-an-tuk-a.

External links

- Iddin-Dagān year-names at CDLI.

- Inanna and Iddin-Dagān at ETCSL.

- A praise poem of Iddin-Dagān at ETCSL.

- An adab to Ningublaga for Iddin-Dagān at ETCSL.

- A namerima (?) for Iddin-Dagān at ETCSL.

References

- ↑ D. O. Edzard (1999). Erich Ebeling; Bruno Meissner, eds. Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie: Ia - Kizzuwatna. 5. Walter De Gruyter Inc. pp. 30–31.

- ↑ David I Owen (October 1971). "Incomplete date formulae of Iddin-Dagān again". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. XXIV (1–2): 17. doi:10.2307/1359342.

- ↑ Daniel T. Potts (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 149, 162.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 BC): Early Periods, Volume 4 (RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia). University of Toronto Press. pp. 77–90.

- ↑ Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson; Gabor Zolyomi, eds. (2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. pp. 262–267.

- ↑ Piotr Michalowski (2008). "The mortal kings of Ur: A short century of divine kingship in ancient Mesopotamia". In Nicole Brisch. Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond. The University of Chicago. pp. 40–41.