Ibex Cave

| Ibex Cave | |

|---|---|

|

Entrance to Ibex Cave. | |

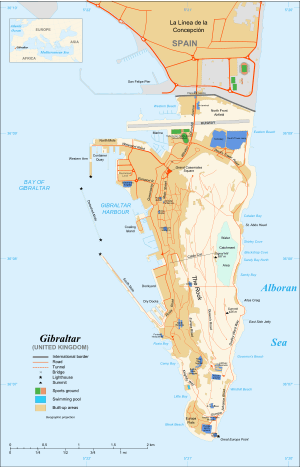

Map showing location of Ibex Cave in Gibraltar. | |

| Location | Eastern face of the Rock of Gibraltar, Gibraltar |

| Coordinates | 36°07′55″N 5°20′39″W / 36.131971°N 5.344149°W |

| Discovery | 1975 [1] |

| Geology | Limestone |

| Entrances | 1 |

Ibex Cave is a limestone cave on the Rock of Gibraltar which has yielded stone artefacts of Mousterian tradition. It was discovered in 1975.[1] It is so named as an ibex skull was found within the cave which would have been hunted by the Neanderthals of Gibraltar thousands of years ago. Ibex Cave was named and excavated by the Gibraltar Museum in 1994. Its first formal description was in 1999.[2]

History

Ibex Cave was named and excavated by the Gibraltar Museum in 1994. Before this, a sand collection operation had been ongoing on the Eastside of the Rock of Gibraltar. The sand from the slopes that was then beneath the water catchments was extracted and transported along a conveyor belt system to the road below for industrial use. The decaying skeleton of this conveyor system was visible from Sir Herbert Miles Road until very recently.[3]

Discovery and rediscovery

In 1985, when workers began removing sand from above the water catchments, they discovered the entrance to a small cave. They recovered stone artefacts and bones until ordered to stop by George Palao of the Public Works Department. Palao gathered the collected items and arranged for the cave to be sealed according to notes found years later in a vault at the Gibraltar Museum. These finds were rediscovered in a bag in 1991 by Prof. Clive Finlayson, Director of the Gibraltar Museum. They included stone tools, made mainly of red jasper and many mammal bones including the almost complete skull of an ibex, a wild mountain goat. In the bag was Palao's report and thus was able to establish where the finds came from. The stone artefacts were of Mousterian tradition, i.e. Neanderthal. A museum collaborator, Julio Gafan, was aware of this find and introduced Prof. Finlayson to one of the former workers at the site who agreed to take them to the site where the artefacts had been recovered.[3]

Writing about the rediscovery, Prof. Finlayson and his wife Dr. Geraldine Finlayson stated:[3]

"Getting to the site was not easy even though we started with the advantage of being able to drive to a middle height on the Rock. This we did by obtaining permission to enter via the Waterworks. Mr Manolo Perez and his deputy, Mr Derek Cano, and their staff have always been most helpful to the Gibraltar Museum and this time was no exception. Having left the car on the west side of the Rock we walked the long and straight tunnel which leads to the huge reservoirs which hold Gibraltar's water supply. Some are the size of two football pitches and during the Second World War one of them housed the Blackwatch Regiment! The moment you enter this quarter-mile long tunnel you literally see the light at the other end. As you walk along it, on the tracks of a small railway system, the opening gets larger and the light brighter. Having got used to the darkness of the inner depths of the Rock you are suddenly confronted with the bright blue of the Mediterranean on the other side.The other side of the Rock is literally another world. Having got there the early morning sun, contrasting with the deep shade of the west side, is then quite warm and agreeable. You look around and you see Catalan Bay below you and the slopes around are covered in a curious mix of introduced caHottentot Figs from South Africa used to stabilise the loose sands, Canary Palms, Tamarisks and native matorral dominated by Lentisc and Olive. The old corrugated sheets of the watercatchments were still prevalent in those early days of 1992.

From the exit to the tunnel we walked south along a passage on the side of which was the channel which used to carry the rainwater into the reservoirs. Throughout the walk we would hear the rattle of stones as they fell onto the sheets from the cliffs above, perhaps disturbed by a gull landing, perhaps accomplices in the millennial process of erosion which, one day, will reduce the Rock to a flat land. We reached a point where we had to abandon the luxury of the passage and start to climb towards the cliff face. The steps here were narrow and a railing to hold onto was not always there. In fact, when there was it was so precarious that it was best not to hold on to it at all! The situation was not for one who suffered from vertigo. The higher we went the smaller Catalan Bay became below us. On either side of us we had corrugated iron sheets so to stumble would have meant a long fall down. A large Tamarisk half-way up right across the steps did little to help as we had to struggle through its branches to get to the other side.

Eventually we conquered the 700 or so steps and reached a sandy platform which had been created by the workers as they removed the sand. We peered over the top and the view was surreal. We can only describe it as a small forest of tobacco plants that had spread and grown here. In the centre of this, then was a bulldozer, apparently taken up there in parts and assembled on site! There were lots of boulders. In many ways getting from here to the cave was the most dangerous part. The boulders were left-overs of the sand removal. Among them were remnants of rusty sheets so there was no guarantee of stability. The cave was a small opening on the cliff side. When we got to it we soon found some prehistoric stone tools and more bones on the surface and we were convinced that this was just the tip of the iceberg. It was at that moment that we knew we had to excavate here.

The cave needed a name. No matter how much we debated we could not reach agreement. Our son, Stewart, then nine years old, stated the obvious – we had found the complete skull of an Ibex (wild mountain goat) so it should be called Ibex Cave. As parents we were not sure. Months later Andy Currant, in his inimical style settled it for us – Stewart named it Ibex Cave, here is the Ibex skull, therefore you must call it Ibex Cave! Who would argue? Two years later, in May 1994, we were digging..."

It is now known that Ibex Cave would have been a hunting station for the Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago, a site where they went to hunt the ibexes. Other fauna associated with the site included the now rare lammergeyer or bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus).[3]

References

- 1 2 "Ibex Cave". NESPOS.org. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ Barton, N. and Currant, A. and Fernandez-Jalvo, Y. and Finlayson, C. and Goldberg, P. and Macphail, R. and Pettitt, P. and Stringer, C. (1999).Gibraltar Neanderthals and results of recent excavations in Gorham's, Vanguard and Ibex Caves.

- 1 2 3 4 Finlayson, Clive; Finlayson, Geraldine (1999). Gibraltar at the end of the Millennium: A Portrait of a Changing Land. Gibraltar: Aquila Services.

- Barton, N. (2000).Gibraltar during the Quaternary: the southernmost part of Europe in the last two million years.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ibex Cave. |