Hydroponics

|

| Agriculture |

|---|

| History |

| Farming |

| Other types |

| Related |

| Lists |

| Categories |

|

|

|

Hydroponics is a subset of hydroculture, the method of growing plants without soil, using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent.[1] Terrestrial plants may be grown with only their roots exposed to the mineral solution, or the roots may be supported by an inert medium, such as perlite or gravel. The nutrients in hydroponics can be from fish waste, duck manure, or normal nutrients.

History

The earliest published work on growing terrestrial plants without soil was the 1627 book Sylva Sylvarum by Francis Bacon, printed a year after his death. Water culture became a popular research technique after that. In 1699, John Woodward published his water culture experiments with spearmint. He found that plants in less-pure water sources grew better than plants in distilled water. By 1842, a list of nine elements believed to be essential for plant growth had been compiled, and the discoveries of German botanists Julius von Sachs and Wilhelm Knop, in the years 1859–1875, resulted in a development of the technique of soilless cultivation.[2] Growth of terrestrial plants without soil in mineral nutrient solutions was called solution culture. It quickly became a standard research and teaching technique and is still widely used. Solution culture is now considered a type of hydroponics where there is no inert medium.

In 1929, William Frederick Gericke of the University of California at Berkeley began publicly promoting that solution culture be used for agricultural crop production.[3][4] He first termed it aquaculture but later found that aquaculture was already applied to culture of aquatic organisms. Gericke created a sensation by growing tomato vines twenty-five feet high in his back yard in mineral nutrient solutions rather than soil.[5] He introduced the term hydroponics, water culture, in 1937, proposed to him by W. A. Setchell, a phycologist with an extensive education in the classics.[6] Hydroponics is derived from neologism ὑδρωρπονικά, constructed in analogy to γεωπονικά,[7] geoponica, that which concerns agriculture, replacing, γεω-, earth, with ὑδρω-, water.[2]

Reports of Gericke's work and his claims that hydroponics would revolutionize plant agriculture prompted a huge number of requests for further information. Gericke had been denied use of the University's greenhouses for his experiments due to the administration's skepticism, and when the University tried to compel him to release his preliminary nutrient recipes developed at home he requested greenhouse space and time to improve them using appropriate research facilities. While he was eventually provided greenhouse space, the University assigned Hoagland and Arnon to re-develop Gericke's formula and show it held no benefit over soil grown plant yields, a view held by Hoagland. In 1940, Gericke published the book, Complete Guide to Soil less Gardening, after leaving his academic position in a climate that was politically unfavorable.[8]

Two other plant nutritionists at the University of California were asked to research Gericke's claims. Dennis R. Hoagland[9] and Daniel I. Arnon[10] wrote a classic 1938 agricultural bulletin, The Water Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil,.[11] Hoagland and Arnon claimed that hydroponic crop yields were no better than crop yields with good-quality soils. Crop yields were ultimately limited by factors other than mineral nutrients, especially light. This research, however, overlooked the fact that hydroponics has other advantages including the fact that the roots of the plant have constant access to oxygen and that the plants have access to as much or as little water as they need. This is important as one of the most common errors when growing is over- and under- watering; and hydroponics prevents this from occurring as large amounts of water can be made available to the plant and any water not used, drained away, recirculated, or actively aerated, eliminating anoxic conditions, which drown root systems in soil. In soil, a grower needs to be very experienced to know exactly how much water to feed the plant. Too much and the plant will be unable to access oxygen; too little and the plant will lose the ability to transport nutrients, which are typically moved into the roots while in solution. These two researchers developed several formulas for mineral nutrient solutions, known as Hoagland solution. Modified Hoagland solutions are still in use.

One of the earliest successes of hydroponics occurred on Wake Island, a rocky atoll in the Pacific Ocean used as a refuelling stop for Pan American Airlines. Hydroponics was used there in the 1930s to grow vegetables for the passengers. Hydroponics was a necessity on Wake Island because there was no soil, and it was prohibitively expensive to airlift in fresh vegetables.

In the 1960s, Allen Cooper of England developed the Nutrient film technique. The Land Pavilion at Walt Disney World's EPCOT Center opened in 1982 and prominently features a variety of hydroponic techniques. In recent decades, NASA has done extensive hydroponic research for its Controlled Ecological Life Support System (CELSS). Hydroponics intended to take place on Mars are using LED lighting to grow in a different color spectrum with much less heat.

Plants that are not traditionally grown in a climate would be possible to grow using a controlled environment system like hydroponics. NASA has also looked to utilize hydroponics in the space program. Ray Wheeler, a plant physiologist at Kennedy Space Center’s Space Life Science Lab, believes that hydroponics will create advances within space travel. He terms this as a bioregenerative life support system.[12]

Techniques

There are two main variations for each medium, sub-irrigation and top irrigation. For all techniques, most hydroponic reservoirs are now built of plastic, but other materials have been used including concrete, glass, metal, vegetable solids, and wood. The containers should exclude light to prevent algae growth in the nutrient solution.

Static solution culture

In static solution culture, plants are grown in containers of nutrient solution, such as glass Mason jars (typically, in-home applications), plastic buckets, tubs, or tanks. The solution is usually gently aerated but may be un-aerated. If un-aerated, the solution level is kept low enough that enough roots are above the solution so they get adequate oxygen. A hole is cut in the lid of the reservoir for each plant. There can be one to many plants per reservoir. Reservoir size can be increased as plant− size increases. A home made system can be constructed from plastic food containers or glass canning jars with aeration provided by an aquarium pump, aquarium airline tubing and aquarium valves. Clear containers are covered with aluminium foil, butcher paper, black plastic, or other material to exclude light, thus helping to eliminate the formation of algae. The nutrient solution is changed either on a schedule, such as once per week, or when the concentration drops below a certain level as determined with an electrical conductivity meter. Whenever the solution is depleted below a certain level, either water or fresh nutrient solution is added. A Mariotte's bottle, or a float valve, can be used to automatically maintain the solution level. In raft solution culture, plants are placed in a sheet of buoyant plastic that is floated on the surface of the nutrient solution. That way, the solution level never drops below the roots.

Continuous-flow solution culture

In continuous-flow solution culture, the nutrient solution constantly flows past the roots. It is much easier to automate than the static solution culture because sampling and adjustments to the temperature and nutrient concentrations can be made in a large storage tank that has potential to serve thousands of plants. A popular variation is the nutrient film technique or NFT, whereby a very shallow stream of water containing all the dissolved nutrients required for plant growth is recirculated past the bare roots of plants in a watertight thick root mat, which develops in the bottom of the channel and has an upper surface that, although moist, is in the air. Subsequent to this, an abundant supply of oxygen is provided to the roots of the plants. A properly designed NFT system is based on using the right channel slope, the right flow rate, and the right channel length. The main advantage of the NFT system over other forms of hydroponics is that the plant roots are exposed to adequate supplies of water, oxygen, and nutrients. In all other forms of production, there is a conflict between the supply of these requirements, since excessive or deficient amounts of one results in an imbalance of one or both of the others. NFT, because of its design, provides a system where all three requirements for healthy plant growth can be met at the same time, provided that the simple concept of NFT is always remembered and practised. The result of these advantages is that higher yields of high-quality produce are obtained over an extended period of cropping. A downside of NFT is that it has very little buffering against interruptions in the flow (e.g. power outages). But, overall, it is probably one of the more productive techniques.

The same design characteristics apply to all conventional NFT systems. While slopes along channels of 1:100 have been recommended, in practice it is difficult to build a base for channels that is sufficiently true to enable nutrient films to flow without ponding in locally depressed areas. As a consequence, it is recommended that slopes of 1:30 to 1:40 are used. This allows for minor irregularities in the surface, but, even with these slopes, ponding and water logging may occur. The slope may be provided by the floor, or benches or racks may hold the channels and provide the required slope. Both methods are used and depend on local requirements, often determined by the site and crop requirements.

As a general guide, flow rates for each gully should be 1 liter per minute. At planting, rates may be half this and the upper limit of 2 L/min appears about the maximum. Flow rates beyond these extremes are often associated with nutritional problems. Depressed growth rates of many crops have been observed when channels exceed 12 metres in length. On rapidly growing crops, tests have indicated that, while oxygen levels remain adequate, nitrogen may be depleted over the length of the gully. As a consequence, channel length should not exceed 10–15 metres. In situations where this is not possible, the reductions in growth can be eliminated by placing another nutrient feed halfway along the gully and halving the flow rates through each outlet.

Aeroponics

Aeroponics is a system wherein roots are continuously or discontinuously kept in an environment saturated with fine drops (a mist or aerosol) of nutrient solution. The method requires no substrate and entails growing plants with their roots suspended in a deep air or growth chamber with the roots periodically wetted with a fine mist of atomized nutrients. Excellent aeration is the main advantage of aeroponics.

Aeroponic techniques have proven to be commercially successful for propagation, seed germination, seed potato production, tomato production, leaf crops, and micro-greens.[13] Since inventor Richard Stoner commercialized aeroponic technology in 1983, aeroponics has been implemented as an alternative to water intensive hydroponic systems worldwide.[14] The limitation of hydroponics is the fact that 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of water can only hold 8 milligrams (0.12 gr) of air, no matter whether aerators are utilized or not.

Another distinct advantage of aeroponics over hydroponics is that any species of plants can be grown in a true aeroponic system because the micro environment of an aeroponic can be finely controlled. The limitation of hydroponics is that only certain species of plants can survive for so long in water before they become waterlogged. The advantage of aeroponics is that suspended aeroponic plants receive 100% of the available oxygen and carbon dioxide to the roots zone, stems, and leaves,[15] thus accelerating biomass growth and reducing rooting times. NASA research has shown that aeroponically grown plants have an 80% increase in dry weight biomass (essential minerals) compared to hydroponically grown plants. Aeroponics used 65% less water than hydroponics. NASA also concluded that aeroponically grown plants requires ¼ the nutrient input compared to hydroponics. Unlike hydroponically grown plants, aeroponically grown plants will not suffer transplant shock when transplanted to soil, and offers growers the ability to reduce the spread of disease and pathogens. Aeroponics is also widely used in laboratory studies of plant physiology and plant pathology. Aeroponic techniques have been given special attention from NASA since a mist is easier to handle than a liquid in a zero-gravity environment.

Fogponics

Fogponics is a derivation of aeroponics wherein the nutrient solution is aerosolized by a diaphragm vibrating at ultrasonic frequencies. Solution droplets produced by this method tend to be 5-10 µm in diameter, smaller than those produced by forcing a nutrient solution through pressurized nozzles, as in aeroponics. The smaller size of the droplets allows them to diffuse through the air more easily, and deliver nutrients to the roots without limiting their access to oxygen.

Passive sub-irrigation

Passive sub-irrigation, also known as passive hydroponics or semi-hydroponics, is a method wherein plants are grown in an inert porous medium that transports water and fertilizer to the roots by capillary action from a separate reservoir as necessary, reducing labor and providing a constant supply of water to the roots. In the simplest method, the pot sits in a shallow solution of fertilizer and water or on a capillary mat saturated with nutrient solution. The various hydroponic media available, such as expanded clay and coconut husk, contain more air space than more traditional potting mixes, delivering increased oxygen to the roots, which is important in epiphytic plants such as orchids and bromeliads, whose roots are exposed to the air in nature. Additional advantages of passive hydroponics are the reduction of root rot and the additional ambient humidity provided through evaporations.

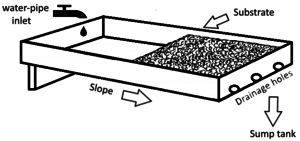

Ebb and flow or flood and drain sub-irrigation

In its simplest form, there is a tray above a reservoir of nutrient solution. Either the tray is filled with growing medium (clay granules being the most common) and planted directly or pots of medium stand in the tray. At regular intervals, a simple timer causes a pump to fill the upper tray with nutrient solution, after which the solution drains back down into the reservoir. This keeps the medium regularly flushed with nutrients and air. Once the upper tray fills past the drain stop, it begins recirculating the water until the timer turns the pump off, and the water in the upper tray drains back into the reservoirs.[16]

Run to waste

In a run-to-waste system, nutrient and water solution is periodically applied to the medium surface. The method was invented in Bengal in 1946, for this reason it is sometimes referred to as "The Bengal System".[17]

This method can be setup in various configurations. In its simplest form, a nutrient-and-water solution is manually applied one or more times per day to a container of inert growing media, such as rockwool, perlite, vermiculite, coco fibre, or sand. In a slightly more complex system, it is automated with a delivery pump, a timer and irrigation tubing to deliver nutrient solution with a delivery frequency that is governed by the key parameters of plant size, plant growing stage, climate, substrate, and substrate conductivity, pH, and water content.

In a commercial setting, watering frequency is multi-factorial and governed by computers or PLCs.

Commercial hydroponics production of large plants like tomatoes, cucumber, and peppers use one form or another of run-to-waste hydroponics.

In environmentally responsible uses, the nutrient rich waste is collected and processed through an on site filtration system to be used many times, making the system very productive.[18]

The majority of bonsai are now grown in soil-free substrates (typically consisting of akadama, grit, diatomaceous earth and other inorganic components) and have their water and nutrients provided in a run-to-waste form.

Deep water culture

The hydroponic method of plant production by means of suspending the plant roots in a solution of nutrient-rich, oxygenated water. Traditional methods favor the use of plastic buckets and large containers with the plant contained in a net pot suspended from the centre of the lid and the roots suspended in the nutrient solution. The solution is oxygen saturated by an air pump combined with porous stones. With this method, the plants grow much faster because of the high amount of oxygen that the roots receive.[19]

Top-fed deep water culture

Top-fed deep water culture is a technique involving delivering highly oxygenated nutrient solution direct to the root zone of plants. While deep water culture involves the plant roots hanging down into a reservoir of nutrient solution, in top-fed deep water culture the solution is pumped from the reservoir up to the roots (top feeding). The water is released over the plant's roots and then runs back into the reservoir below in a constantly recirculating system. As with deep water culture, there is an airstone in the reservoir that pumps air into the water via a hose from outside the reservoir. The airstone helps add oxygen to the water. Both the airstone and the water pump run 24 hours a day.

The biggest advantage of top-fed deep water culture over standard deep water culture is increased growth during the first few weeks. With deep water culture, there is a time when the roots have not reached the water yet. With top-fed deep water culture, the roots get easy access to water from the beginning and will grow to the reservoir below much more quickly than with a deep water culture system. Once the roots have reached the reservoir below, there is not a huge advantage with top-fed deep water culture over standard deep water culture. However, due to the quicker growth in the beginning, grow time can be reduced by a few weeks.[20]

Rotary

A rotary hydroponic garden is a style of commercial hydroponics created within a circular frame which rotates continuously during the entire growth cycle of whatever plant is being grown.

While system specifics vary, systems typically rotate once per hour, giving a plant 24 full turns within the circle each 24-hour period. Within the center of each rotary hydroponic garden is a high intensity grow light, designed to simulate sunlight, often with the assistance of a mechanized timer.

Each day, as the plants rotate, they are periodically watered with a hydroponic growth solution to provide all nutrients necessary for robust growth. Due to the plants continuous fight against gravity, plants typically mature much more quickly than when grown in soil or other traditional hydroponic growing systems.[21] Due to the small foot print a rotary hydroponic system has, it allows for more plant material to be grown per sq foot of floor space than other traditional hydroponic systems.

Substrates

One of the most obvious decisions hydroponic farmers have to make is which medium they should use. Different media are appropriate for different growing techniques.

Expanded clay aggregate

Baked clay pellets are suitable for hydroponic systems in which all nutrients are carefully controlled in water solution. The clay pellets are inert, pH neutral and do not contain any nutrient value.

The clay is formed into round pellets and fired in rotary kilns at 1,200 °C (2,190 °F). This causes the clay to expand, like popcorn, and become porous. It is light in weight, and does not compact over time. The shape of an individual pellet can be irregular or uniform depending on brand and manufacturing process. The manufacturers consider expanded clay to be an ecologically sustainable and re-usable growing medium because of its ability to be cleaned and sterilized, typically by washing in solutions of white vinegar, chlorine bleach, or hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), and rinsing completely.

Another view is that clay pebbles are best not re-used even when they are cleaned, due to root growth that may enter the medium. Breaking open a clay pebble after a crop has been shown to reveal this growth.

Growstones

Growstones, made from glass waste, have both more air and water retention space than perlite and peat. This aggregate holds more water than parboiled rice hulls.[22] Growstones by volume consist of 0.5 to 5% calcium carbonate[23] – for a standard 5.1 kg bag of Growstones that corresponds to 25.8 to 258 grams of calcium carbonate. The remainder is soda-lime glass.[23]

Coir peat

Coco peat, also known as coir or coco, is the leftover material after the fibres have been removed from the outermost shell (bolster) of the coconut. Coir is a 100% natural grow and flowering medium. Coconut coir is colonized with trichoderma fungi, which protects roots and stimulates root growth. It is extremely difficult to over-water coir due to its perfect air-to-water ratio; plant roots thrive in this environment. Coir has a high cation exchange, meaning it can store unused minerals to be released to the plant as and when it requires it. Coir is available in many forms; most common is coco peat, which has the appearance and texture of soil but contains no mineral content.

Rice husks

Parboiled rice husks (PBH) are an agricultural byproduct that would otherwise have little use. They decay over time, and allow drainage,[24] and even retain less water than growstones.[22] A study showed that rice husks did not affect the effects of plant growth regulators.[24]

Perlite

Perlite is a volcanic rock that has been superheated into very lightweight expanded glass pebbles. It is used loose or in plastic sleeves immersed in the water. It is also used in potting soil mixes to decrease soil density. Perlite has similar properties and uses to vermiculite but, in general, holds more air and less water. If not contained, it can float if flood and drain feeding is used. It is a fusion of granite, obsidian, pumice and basalt. This volcanic rock is naturally fused at high temperatures undergoing what is called "Fusionic Metamorphosis".

Vermiculite

Like perlite, vermiculite is a mineral that has been superheated until it has expanded into light pebbles. Vermiculite holds more water than perlite and has a natural "wicking" property that can draw water and nutrients in a passive hydroponic system. If too much water and not enough air surrounds the plants roots, it is possible to gradually lower the medium's water-retention capability by mixing in increasing quantities of perlite.

Pumice

Like perlite, pumice is a lightweight, mined volcanic rock that finds application in hydroponics.

Sand

Sand is cheap and easily available. However, it is heavy, does not hold water very well, and it must be sterilized between uses.

Gravel

The same type that is used in aquariums, though any small gravel can be used, provided it is washed first. Indeed, plants growing in a typical traditional gravel filter bed, with water circulated using electric powerhead pumps, are in effect being grown using gravel hydroponics. Gravel is inexpensive, easy to keep clean, drains well and will not become waterlogged. However, it is also heavy, and, if the system does not provide continuous water, the plant roots may dry out.

Wood fibre

Wood fibre, produced from steam friction of wood, is a very efficient organic substrate for hydroponics. It has the advantage that it keeps its structure for a very long time. Wood wool (i.e. wood slivers) have been used since the earliest days of the hydroponics research.[8] However, more recent research suggests that wood fibre may have detrimental effects on "plant growth regulators".[24]

Sheep wool

Wool from shearing sheep is a little-used yet promising renewable growing medium. In a study comparing wool with peat slabs, coconut fibre slabs, perlite and rockwool slabs to grow cucumber plants, sheep wool had a greater air capacity of 70%, which decreased with use to a comparable 43%, and water capacity that increased from 23% to 44% with use.[25] Using sheep wool resulted in the greatest yield out of the tested substrates, while application of a biostimulator consisting of humic acid, lactic acid and Bacillus subtilis improved yields in all substrates.[25]

Rock wool

Rock wool (mineral wool) is the most widely used medium in hydroponics. Rock wool is an inert substrate suitable for both run-to-waste and recirculating systems. Rock wool is made from molten rock, basalt or 'slag' that is spun into bundles of single filament fibres, and bonded into a medium capable of capillary action, and is, in effect, protected from most common microbiological degradation. Rock wool has many advantages and some disadvantages. The latter being the possible skin irritancy (mechanical) whilst handling (1:1000). Flushing with cold water usually brings relief. Advantages include its proven efficiency and effectiveness as a commercial hydroponic substrate. Most of the rock wool sold to date is a non-hazardous, non-carcinogenic material, falling under Note Q of the European Union Classification Packaging and Labeling Regulation (CLP).

Brick shards

Brick shards have similar properties to gravel. They have the added disadvantages of possibly altering the pH and requiring extra cleaning before reuse.

Polystyrene packing peanuts

Polystyrene packing peanuts are inexpensive, readily available, and have excellent drainage. However, they can be too lightweight for some uses. They are used mainly in closed-tube systems. Note that polystyrene peanuts must be used; biodegradable packing peanuts will decompose into a sludge. Plants may absorb styrene and pass it to their consumers; this is a possible health risk.

Nutrient solutions

Inorganic hydroponic solutions

The formulation of hydroponic solutions is an application of plant nutrition, with nutrient deficiency symptoms mirroring those found in traditional soil based agriculture. However, the underlying chemistry of hydroponic solutions can differ from soil chemistry in many significant ways. Important differences include:

- Unlike soil, hydroponic nutrient solutions do not have cation-exchange capacity (CEC) from clay particles or organic matter. The absence of CEC means the pH and nutrient concentrations can change much more rapidly in hydroponic setups than is possible in soil.

- Selective absorption of nutrients by plants often imbalances the amount of counterions in solution.[8][26][27] This imbalance can rapidly affect solution pH and the ability of plants to absorb nutrients of similar ionic charge (see article membrane potential). For instance, nitrate anions are often consumed rapidly by plants to form proteins, leaving an excess of cations in solution.[8] This cation imbalance can lead to deficiency symptoms in other cation based nutrients (e.g. Mg2+) even when an ideal quantity of those nutrients are dissolved in the solution.[26][27]

- Depending the on pH, and/or the presence of water contaminants, nutrients, such as iron, can precipitate from the solution and become unavailable to plants. Routine adjustments to pH, buffering the solution, and/or the use of chelating agents is often necessary.

As in conventional agriculture, nutrients should be adjusted to satisfy Liebig's law of the minimum for each specific plant variety.[26] Nevertheless, generally acceptable concentrations for nutrient solutions exist, with minimum and maximum concentration ranges for most plants being somewhat similar. Most nutrient solutions are mixed to have concentrations between 1,000 and 2,500 ppm.[8] Acceptable concentrations for the individual nutrient ions, which comprise that total ppm figure, are summarized in the following table. For essential nutrients, concentrations below these ranges often lead to nutrient deficiencies while exceeding these ranges can lead to nutrient toxicity. Optimum nutrition concentrations for plant varieties are found empirically by experience and/or by plant tissue tests.[26]

| Element | Role | Ionic form(s) | Low range (ppm) | High range (ppm) | Common Sources | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | Essential macronutrient | NO− 3 and/or NH+ 4 | 100[27] | 1000[26] | KNO3, NH4NO3, Ca(NO3)2, HNO3, (NH4)2SO4, and (NH4)2HPO4 | NH+ 4 interferes with Ca2+ uptake and can be toxic to plants if used as a major nitrogen source. A 3:1 ratio of NO− 3 to NH+ 4 is sometimes recommended to balance pH during nitrogen absorption.[27] |

| Potassium | Essential macronutrient | K+ | 100[26] | 400[26] | KNO3, K2SO4, KCl, KOH, K2CO3, K2HPO4, and K2SiO3 | High concentrations interfere with the function Fe, Mn, and Zn. Zinc deficiencies often are the most apparent.[27] |

| Phosphorus | Essential macronutrient | PO3− 4 | 30[27] | 100[26] | K2HPO4, KH2PO4, NH4H2PO4, H3PO4, and Ca(H2PO4)2 | Excess NO− 3 tends to inhibit PO3− 4 absorption. The ratio of iron to PO3− 4 can affect co-preciptiation reactions.[26] |

| Calcium | Essential macronutrient | Ca2+ | 200[27] | 500[26] | Ca(NO3)2, Ca(H2PO4), CaSO4, CaCl2 | Excess Ca2+ inhibits Mg2+ uptake.[27] |

| Magnesium | Essential macronutrient | Mg2+ | 50[26] | 100[26] | MgSO4 and MgCl2 | Should not exceed Ca2+ concentration due to competitive uptake.[27] |

| Sulfur | Essential macronutrient | SO2− 4 | 50[27] | 1000[26] | MgSO4, K2SO4, CaSO4, H2SO4, (NH4)2SO4, ZnSO4, CuSO4, FeSO4, and MnSO4 | Unlike most nutrients, plants can tolerate a high concentration of the SO2− 4, selectively absorbing the nutrient as needed.[8][26][27] Undesirable counterion affects still apply however. |

| Iron | Essential micronutrient | Fe3+ and Fe2+ | 2[27] | 5[26] | FeDTPA, FeEDTA, iron citrate, iron tartrate, FeCl3, and FeSO4 | pH values above 6.5 greatly decreases iron solubility. Chelating agents (e.g. DTPA, citric acid, or EDTA) are often added to increase iron solubility over a greater pH range.[27] |

| Zinc | Essential micronutrient | Zn2+ | 0.05[27] | 1[26] | ZnSO4 | Excess zinc is highly toxic to plants but is essential for plants at low concentrations. |

| Copper | Essential micronutrient | Cu2+ | 0.01[27] | 1[26] | CuSO4 | Plant sensitivity to copper is highly variable. 0.1 ppm can cause toxic to some plants[27] while a concentration up to 0.5 ppm for many plants is often considered ideal.[26] |

| Manganese | Essential micronutrient | Mn2+ | 0.5[26][27] | 1[26] | MnSO4 and MnCl2 | Uptake is enhanced by high PO3− 4 concentrations.[27] |

| Boron | Essential micronutrient | B(OH)− 4 | 0.3[27] | 10[26] | H3BO3, and Na2B4O7 | An essential nutrient, however, some plants are highly sensitive to boron (e.g. toxic affects are apparent in citrus trees at 0.5 ppm).[26] |

| Molybdenum | Essential micronutrient | MoO− 4 | 0.001[26] | 0.05[27] | (NH4)6Mo7O24 and Na2MoO4 | A component of the enzyme nitrate reductase and required by rhizobia for nitrogen fixation.[27] |

| Nickel | Essential micronutrient | Ni2+ | 0.057[27] | 1.5[26] | NiSO4 and NiCO3 | Essential to many plants (e.g. legumes and some grain crops).[27] Also used in the enzyme urease. |

| Chlorine | Variable micronutrient | Cl− | 0 | Highly variable | KCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, and NaCl | Can interfere with NO− 3 uptake in some plants but can be beneficial in some plants (e.g. in asparagus at 5 ppm). Absent in conifers, ferns, and most bryophytes.[26] |

| Aluminum | Variable micronutrient | Al3+ | 0 | 10[26] | Al2(SO4)3 | Essential for some plants (e.g. peas, maize, sunflowers, and cereals). Can be toxic to some plants below 10 ppm.[26] Sometimes used to produce flower pigments (e.g. by Hydrangeas). |

| Silicon | Variable micronutrient | SiO2− 3 | 0 | 140[27] | K2SiO3, Na2SiO3, and H2SiO3 | Present in most plants, abundant in cereal crops, grasses, and tree bark. Evidence that SiO2− 3 improves plant disease resistance exists.[26] |

| Titanium | Variable micronutrient | Ti3+ | 0 | 5[26] | H4TiO4 | Might be essential but trace Ti3+ is so ubiquitous that its addition is rarely warranted.[27] At 5 ppm favorable growth effects in some crops are notable (e.g. pineapple and peas).[26] |

| Cobalt | Non-essential micronutrient | Co2+ | 0 | 0.1[26] | CoSO4 | Required by rhizobia, important for legume root nodulation.[27] |

| Sodium | Non-essential micronutrient | Na+ | 0 | Highly variable | Na2SiO3, Na2SO4, NaCl, NaHCO3, and NaOH | Na+ can partially replace K+ in some plant functions but K+ is still an essential nutrient.[26] |

| Vanadium | Non-essential micronutrient | VO2+ | 0 | Trace, undetermined | VOSO4 | Beneficial for rhizobial N2 fixation.[27] |

| Lithium | Non-essential micronutrient | Li+ | 0 | Undetermined | Li2SO4, LiCl, and LiOH | Li+ can increase the chlorophyll content of some plants (e.g. potato and pepper plants).[27] |

Organic hydroponic solutions

Organic fertilizers can be used to supplement or entirely replace the inorganic compounds used in conventional hydroponic solutions.[26][27] However, using organic fertilizers introduces a number of challenges that are not easily resolved. Examples include:

- organic fertilizers are highly variable in their nutritional compositions. Even similar materials can differ significantly based on their source (e.g. the quality of manure varies based on an animal's diet).

- organic fertilizers are often sourced from animal byproducts, making disease transmission a serious concern for plants grown for human consumption or animal forage.

- organic fertilizers are often particulate and can clog substrates or other growing equipment. Sieving and/or milling the organic materials to fine dusts is often necessary.

- some organic materials (i.e. particularly manures and offal) can further degrade to emit foul odors.

Nevertheless, if precautions are taken, organic fertilizers can be used successfully in hydroponics.[26][27]

Organically sourced macronutrients

Examples of suitable materials, with their average nutritional contents tabulated in terms of percent dried mass, are listed in the following table.[26]

| Organic material | N | P2O5 | K2O | CaO | MgO | SO2 | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodmeal | 13.0% | 2.0% | 1.0% | 0.5% | – | – | |

| Bone ashes | – | 35.0% | – | 46.0% | 1.0% | 0.5% | |

| Bonemeal | 4.0% | 22.5% | – | 33.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% | |

| Hoof / Horn meal | 14.0% | 1.0% | – | 2.5% | – | 2.0% | |

| Fishmeal | 9.5% | 7.0% | – | 0.5% | – | – | |

| Wool waste | 3.5% | 0.5% | 2.0% | 0.5% | – | – | |

| Wood ashes | – | 2.0% | 5.0% | 33.0% | 3.5% | 1.0% | |

| Cottonseed ashes | – | 5.5% | 27.0% | 9.5% | 5.0% | 2.5% | |

| Cottonseed meal | 7.0% | 3.0% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% | – | |

| Dried locust or grasshopper | 10.0% | 1.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | – | – | |

| Leather waste | 5.5% to 22% | – | – | – | – | – | Milled to a fine dust.[27] |

| Kelp meal, liquid seaweed | 1% | – | 12% | – | – | – | Commercial products available. |

| Poultry manure | 2% to 5% | 2.5% to 3% | 1.3% to 3% | 4.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | A liquid compost which is sieved to remove solids and checked for pathogens.[26] |

| Sheep manure | 2.0% | 1.5% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 2.0% | 1.5% | Same as poultry manure. |

| Goat manure | 1.5% | 1.5% | 3.0% | 2.0% | – | – | Same as poultry manure. |

| Horse manure | 3% to 6% | 1.5% | 2% to 5% | 1.5% | 1.0% | 0.5% | Same as poultry manure. |

| Cow manure | 2.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 4.0% | 1.1% | 0.5% | Same as poultry manure. |

| Bat guano | 8.0% | 40% | 29% | Trace | Trace | Trace | High in micronutrients.[27] Commercially available. |

| Bird guano | 13% | 8% | 20% | Trace | Trace | Trace | High in micronutrients. Commercially available. |

Organically sourced micronutrients

Micronutrients can be sourced from organic fertilizers as well. For example, composted pine bark is high in manganese and is sometimes used to fulfill that mineral requirement in hydroponic solutions.[27] To satisfy requirements for National Organic Programs, pulverized, unrefined minerals (e.g. Gypsum, Calcite, and glauconite) can also be added to satisfy a plant's nutritional needs.

Additives

In addition to chelating agents, humic acids can be added to increase nutrient uptake.[27][28]

Tools

Common equipment

Managing nutrient concentrations and pH values within acceptable ranges is essential for successful hydroponic horticulture. Common tools used to manage hydroponic solutions include:

- Electrical conductivity meters, a tool which estimates nutrient ppm by measuring how well a solution transmits an electric current.

- pH meter, a tool that uses an electric current to determine the concentration of hydrogen ions in solution.

- Litmus paper, disposable pH indicator strips that determine hydrogen ion concentrations by color changing chemical reaction.

- Graduated cylinders or measuring spoons to measure out premixed, commercial hydroponic solutions.

Advanced equipment

Advanced equipment can also be used to perform accurate chemical analyses of nutrient solutions. Examples include:[26]

- Balances for accurately measuring materials.

- Laboratory glassware, such as burettes and pipettes, for performing titrations.

- Colorimeters for solution tests which apply the Beer–Lambert law.

Using advanced equipment for hydroponic solutions can be beneficial to growers of any background because nutrient solutions are often reusable.[29] Because nutrient solutions are virtually never completely depleted, and should never be due to the unacceptably low osmotic pressure that would result, re-fortification of old solutions with new nutrients can save growers money and can control point source pollution, a common source for the eutrophication of nearby lakes and streams.[29]

Software

Although pre-mixed concentrated nutrient solutions are generally purchased from commercial nutrient manufacturers by hydroponic hobbyists and small commercial growers, several tools exist to help anyone prepare their own solutions without extensive knowledge about chemistry. The free and open source tools HydroBuddy[30] and HydroCal[31] have been created by professional chemists to help any hydroponics grower prepare their own nutrient solutions. The first program is available for Windows, Mac and Linux while the second one can be used through a simple JavaScript interface. Both programs allow for basic nutrient solution preparation although HydroBuddy provides added functionality to use and save custom substances, save formulations and predict electrical conductivity values.

Mixing solutions

Often mixing hydroponic solutions using individual salts is impractical for hobbyists and/or small-scale commercial growers because commercial products are available at reasonable prices. However, even when buying commercial products, multi-component fertilizers are popular. Often these products are bought as three part formulas which emphasize certain nutritional roles. For example, solutions for vegetative growth (i.e. high in nitrogen), flowering (i.e. high in potassium and phosphorus), and micronutrient solutions (i.e. with trace minerals) are popular. The timing and application of these multi-part fertilizers should coincide with a plant's growth stage. For example, at the end of an annual plant's life cycle, a plant should be restricted from high nitrogen fertilizers. In most plants, nitrogen restriction inhibits vegetative growth and helps induce flowering.[27]

Advancements

With pest problems reduced and nutrients constantly fed to the roots, productivity in hydroponics is high; however, growers can further increase yield by manipulating a plant's environment by constructing sophisticated growrooms.

CO2 enrichment

To increase yield further, some sealed greenhouses inject CO2 into their environment to help improve growth and plant fertility.

See also

- Aeroponics

- Aquaponics

- Fogponics

- Folkewall

- Grow box

- Growroom

- Organoponics

- Passive hydroponics

- Plant factory

- Plant nutrition

- Plant pathology

- Root rot

- Vertical farming

- Xeriscaping

References

- ↑ Santos, J. D. et al (2013) Development of a vinasse nutritive solutions for hydroponics. Journal of Environmental Management 114: 8-12.

- 1 2 Douglas, James S., Hydroponics, 5th ed. Bombay: Oxford UP, 1975. 1–3

- ↑ Dunn, H. H. (October 1929). "Plant "Pills" Grow Bumper Crops". Popular Science Monthly: 29.

- ↑ G. Thiyagarajan, R. Umadevi & K. Ramesh, "Hydroponics," Science Tech Entrepreneur, (January 2007), Water Technology Centre, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641 003, India. Archived December 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bambi Turner, "How Hydroponics Works," HowStuffWorks.com. Retrieved: 29-05-2012

- ↑ Berkeley, biography Archived March 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Liddell & Scott, geoponikos

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gericke, William F. (1940). The Complete Guide to Soilless Gardening (1st ed.). London: Putnam. pp. 9–10, 38 & 84. ISBN 9781163140499.

- ↑ "Dennis Robert Hoagland from Encyclopaedia Britannica American Botanist".

- ↑ Archived April 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Water Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil

- ↑ Anna Heiney, "Farming for the Future", nasa.gov, 8-27-04

- ↑ Research News. "Commercial Aeroponics: The Grow Anywhere Story," In Vitro Report (Society for In Vitro Biology), Issue 42.2 (April – June 2008).

- ↑ "Stoner, R., "Aeroponics Versus Bed and Hydroponic Propagation", Florist Review, Vol 173 no.4477, September 22, 1983".

- ↑ Stoner, R.J (1983). Rooting in Air. Greenhouse Grower Vol I No. 11

- ↑ "Flood and Drain or Ebb and Flow". www.makehydroponics.com. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ↑ Douglas, James Sholto (1975). Hydroponics: The Bengal System (5th ed.). New Dehli: Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780195605662.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Newagehydro.com. Retrieved 2011-09-20.

- ↑ "Deep Water Culture". Growell. Archived from the original on 2010-04-13.

- ↑ "Growing Cannabis with Bubbleponics". GrowWeedEasy.com. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ [http:www.hydroponicbucket.com/uses

- 1 2 (2011). "Growstones ideal alternative to perlite, parboiled rice hulls". American Society for Horticultural Science http://esciencenews.com/articles/2011/12/14/growstones.ideal.alternative.perlite.parboiled.rice.hulls

- 1 2 . GrowStone MSDS. http://sunlightsupply.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/product/714230_MSDS.pdf

- 1 2 3 Wallheimer, Brian (October 25, 2010). "Rice hulls a sustainable drainage option for greenhouse growers". Purdue University. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- 1 2 M. Böhme; J. Schevchenko; I. Pinker; S. Herfort (2005). "Cucumber grown in sheepwool slabs treated with biostimulator compared to other organic and mineral substrates". ISHS Acta Horticulturae 779: International Symposium on Growing Media. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Sholto Douglas, James (1985). Advanced guide to hydroponics: (soiless cultivation). London: Pelham Books. pp. 169–187, 289–320, & 345–351. ISBN 9780720715712.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 J. Benton, Jones (2004). Hydroponics: A Practical Guide for the Soilless Grower (2nd ed.). Newyork: Taylor & Francis. pp. 29–70 & 225–229. ISBN 9780849331671.

- ↑ Adania, Fabrizio; Genevinia, Pierluigi; Zaccheoa, Patrizia; Zocchia, Graziano (1998). "The effect of commercial humic acid on tomato plant growth and mineral nutrition". Journal of Plant Nutrition. 21 (3): 561–575. doi:10.1080/01904169809365424.

- 1 2 Kumar, Ramasamy Rajesh; Cho, Jae Young (2014). "Reuse of hydroponic waste solution". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 21 (16): 9569–9577. doi:10.1007/s11356-014-3024-3.

- ↑ HydroBuddy : A crowd-sourced community platform which gives alerts about chemistry and new grow protocols Eddy An Open Source Multi-Platform Hydroponic Nutrient Calculator

- ↑ HydroCal : A JavaScript Hydroponic Nutrient Calculator

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Hydroculture |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hydroponics. |