Hursag

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

|

Demigods and heroes |

| Related topics |

Hursag (transcribed cuneiform: ḫur.saḡ(HUR.SAG)) is a Sumerian term variously translated as meaning "mountain", "hill", "foothills" or "piedmont".[1] Thorkild Jacobsen extrapolated the translation in his later career to mean literally, "head of the valleys".[2]

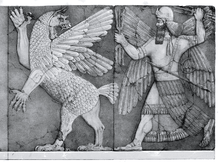

Mountains play a certain role in Mesopotamian mythology and Assyro-Babylonian religion, associated with deities such as Anu, Enlil, Enki and Ninhursag.

Some scholars also identify hursag with an undefined mountain range or strip of raised land outside the plain of Mesopotamia.[3][4]

In a myth variously entitled by Samuel Noah Kramer as “The Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta” and later Ninurta Myth Lugal-e by Thorkild Jacobsen, Hursag is described as a mound of stones constructed by Ninurta after his defeat of a demon called Asag. Ninurta’s mother Ninlil visits the location after this great victory. In return for her love and loyalty, Ninurta gives Ninlil the hursag as a gift. Her name is consequentially changed from Ninlil to Ninhursag or the “mistress of the Hursag”.[5][6]

The hursag is described here in a clear cultural myth as a high wall, levee, dam or floodbank, used to restrain the excess mountain waters and floods caused by the melting snow and spring rain. The hursag is constructed with Ninurta's skills in irrigation engineering and employed to improve the agriculture of the surrounding lands, farms and gardens where the water had previously been wasted.[6]

Ninurta Myth Lugal-e describes the abundance of the Hursag:

| “ | ”I, a warrior have heaped up be Hursag, and be you it’s owner!” -At once, by Ninurta’s decree, thus it verily became; she is today to be spoken of (as) Ninhursaga- ”May its meadows grow herbs for you, may its ledges grow grapevines and (yield) grape sirop for you, may its slopes grow cedar, cypress, supalu-trees and box for you, with tree fruit like an orchard, may the foothills make great scent of godliness for you, may gold and silver be mined for you and may HI-IB-LAL be made for you. May it smelt copper and tin for you may it pay you its tribute, may the highland make goats and wild asses numerous for you, may the Hursag have the four-legged beasts bring forth offspring for you.[6] |

” |

Notes

- ↑ Thorkild Jacobsen; I. Tzvi Abusch (2002). Riches hidden in secret places: ancient Near Eastern studies in memory of Thorkild Jacobsen. Eisenbrauns. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-57506-061-3. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ↑ Biggs, Robert D., Studies presented to Robert D. Biggs, June 4, 2004, , Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, p.223, 30 Jan 2008

- ↑ Richard J. Clifford (1972). The cosmic mountain in Canaan and the Old Testament. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ M. Mindlin; Markham J. Geller; John E. Wansbrough (1987). Figurative language in the ancient Near East. Psychology Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-7286-0141-3. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (January 1979). From the Poetry of Sumer: Creation, Glorification, Adoration. University of California Press. pp. 38, 39–. ISBN 978-0-520-03703-8.

- 1 2 3 The Harps that Once--: Sumerian Poetry in Translation. Yale University Press. 1 September 1997. pp. 234–235, 254–255. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5.