Humber River (Ontario)

| Humber River | |

| River | |

The Humber, as seen from a point near the northern border of Toronto | |

| Country | Canada |

|---|---|

| Province | Ontario |

| Region | Southern Ontario |

| Districts | Dufferin County, Regional Municipality of Peel, Simcoe County, Regional Municipality of York |

| Municipalities | Toronto, Adjala–Tosorontio, Brampton, Caledon, King, Mono, Vaughan |

| Part of | Great Lakes Basin |

| Source | Humber Springs Ponds |

| - location | Mono, Dufferin County |

| - elevation | 421 m (1,381 ft) |

| - coordinates | 43°56′36″N 80°00′14″W / 43.94333°N 80.00389°W |

| Mouth | Humber Bay, Lake Ontario |

| - location | Toronto |

| - elevation | 74 m (243 ft) |

| - coordinates | 43°37′56″N 79°28′19″W / 43.63222°N 79.47194°WCoordinates: 43°37′56″N 79°28′19″W / 43.63222°N 79.47194°W |

| Length | 100 km (62 mi) |

| Basin | 903 km2 (349 sq mi) |

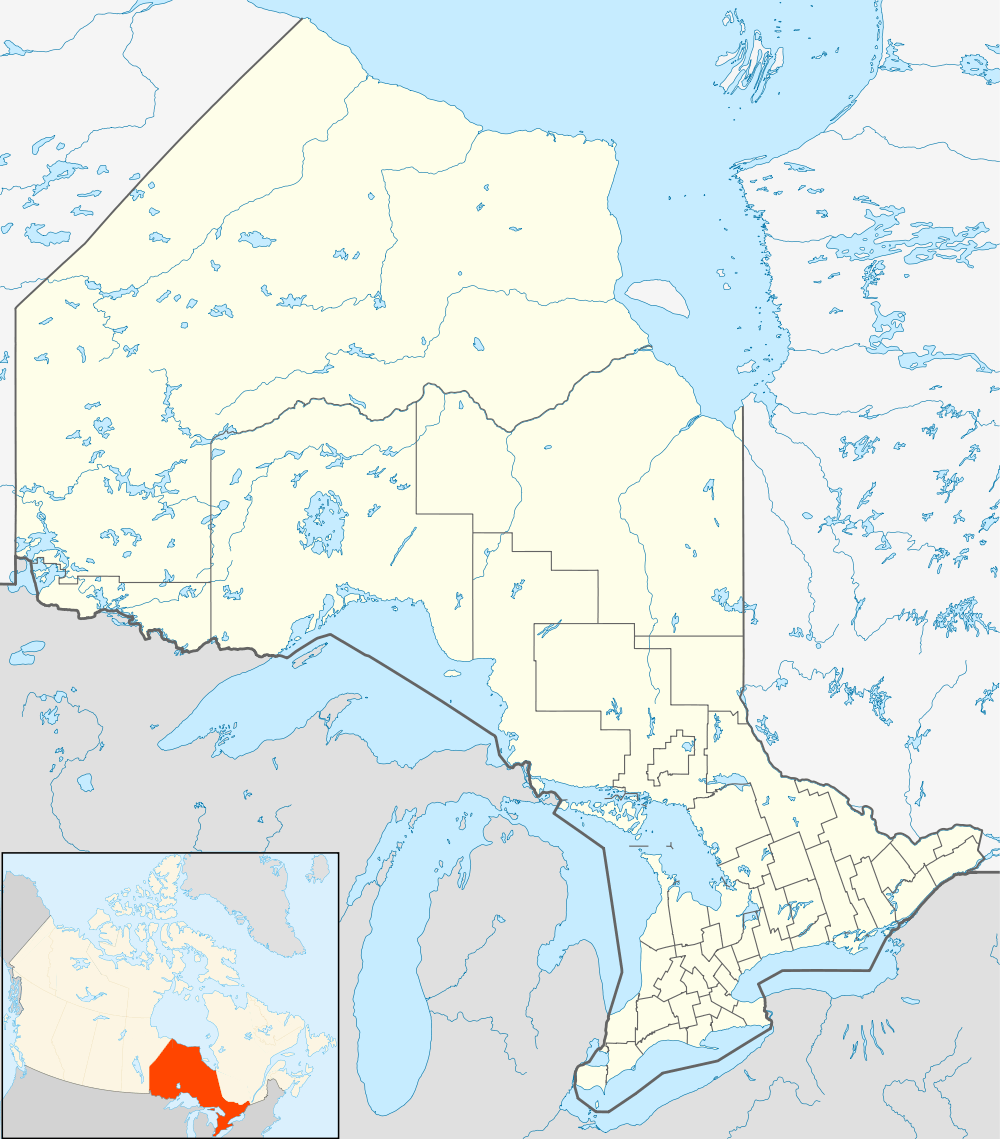

Location of the mouth of the Humber River in Ontario | |

The Humber River (French: Rivière Humber) is a river in Southern Ontario, Canada.[1] It is in the Great Lakes Basin, is a tributary of Lake Ontario and is one of two major rivers on either side of the city of Toronto, the other being the Don River to the east. It was designated a Canadian Heritage River on September 24, 1999.[2]

The Humber collects from about 750 creeks and tributaries in a fan-shaped area north of Toronto that encompasses portions of Dufferin County, the Regional Municipality of Peel, Simcoe County, and the Regional Municipality of York. The main branch runs for about 100 kilometres (60 mi)[2] from the Niagara Escarpment in the northwest, while another other major branch, known as the East Humber River, starts at Lake St. George in the Oak Ridges Moraine near Aurora to the northeast. They join north of Toronto and then flow in a generally southeasterly direction into Lake Ontario at what was once the far western portions of the city.[3] The river mouth is flanked by Sir Casimir Gzowski Park and Humber Bay Park East.

Naming

The Anishinaabe, the most recent native inhabitants of the area, refer to the river as Cobechenonk, for “leave the canoes and go back.”[4] During the 1600s and 1700s, the river was known by several names before it was given the official name of Humber. Popple's map of 1733 shows a prominent river beside the native settlement "Tejajagon" assumed to be the Humber. Its name is given as the Tanaovate River.[5] The river was also known as the "Toronto River." Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe gave the river the name of Humber, likely after the Humber estuary in England.[6]

History

The Humber has a long history of human settlement along its banks. Native settlement of the area is well documented archaeologically and occurred in three waves. The first settlers were the Palaeo-Indians who lived in the area from 10,000 to 7000 BC. The second wave, people of the Archaic period, settled the area between 7000 and 1000 BC and began to adopt seasonal migration patterns to take advantage of available plants, fish, and game. The third wave of native settlement was the Woodland period, which saw the introduction of the bow and arrow and the growing of crops which allowed for larger, more permanent villages. The Woodland period was also characterized by movement of native groups along what is known today as the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail, running from Lake Ontario up the Humber to Lake Simcoe and eventually to the northern Great Lakes.[2]

Étienne Brûlé was the first European to encounter the Humber while travelling the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail. Brûlé passed through the watershed in 1615 on a mission from Samuel de Champlain to build alliances with native peoples. The Trail became a convenient shortcut to the upper Great Lakes for traders, explorers, and missionaries. A major landmark on the northern end of the trail in Lake Simcoe was used to describe the trail as a whole, and eventually the southern end became known simply as "Toronto" to the Europeans.[2]

A fort, Fort Toronto, was constructed about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) inland from the mouth of the Humber to protect the Trail. During the 1660s this was the site of Teiaiagon, a permanent settlement of the Seneca used for trading with the Europeans. Popple's map of 1733 shows a prominent river beside "Tejajagon" which is assumed to be the Humber. French missionaries used the area for many years, including Jean de Brébeuf and Joseph Chaumonot in 1641, Louis Hennepin in 1678, and Rene-Robert Cavelier de La Salle in 1680.[2]

However, no permanent European settlement occurred until the arrival of Jean-Baptiste Rousseau (not to be confused with Jean-Jacques, the famous author) in the late 18th century. Rousseau piloted John Graves Simcoe's ship into Toronto Bay to officially begin the British era of control in 1793. Most of the British attention was focussed to the east of the Humber, around the protected Toronto Bay closer to the Don River. Settlement was scattered until after the War of 1812 when many loyalists moved to the area, who were joined by immigrants from Ireland and Scotland who chose to remain in British lands.[2]

Upon his arrival in York, Simcoe was keenly aware of the need for a lumber mill and grist mill in the area. He had constructed a sawmill on the west bank of the river near present-day Bloor Street in 1793, which was operated by John Wilson. In 1797 Simcoe managed to get a grist mill established on the Humber River. It was owned and operated by John Lawrence. Over the years, numerous mills have been operated along the river by such men as William Cooper, W. P. Howland, Thomas Fisher, John Scarlett, William Gamble and Joseph Rowntree. The last grist mill on the Humber, Hayhoe Mills in Woodbridge, closed in 2007.

By 1860 the Humber Valley was extensively deforested. This decreased the stability of the river banks and increased damages done by periodic flooding. In 1878 a disastrous flood destroyed the remaining water powered mills. As the Toronto area grew, the lands around the Humber became important farming areas; in addition, some areas of the river's flood plain were developed as residential. This led to serious runoff problems in the 1940s, which the Humber Valley Conservation Authority was established to address. But in 1954, Hurricane Hazel raised the river to devastating flood levels, destroying buildings and bridges; on Raymore Drive, 60 homes were destroyed and 35 people were killed.

The Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA later TRCA) succeeded the Humber Valley authority in 1957 (the word "Metropolitan" was dropped in 1998).[2] More recently, a task force within the Authority was formed to further clear the Humber as a part of the Great Lakes 2000 Cleanup Fund.

Course

For a map showing the river course, see this reference.[3]

The Humber River begins at Humber Springs Ponds on the Niagara Escarpment in Mono, Dufferin County[2] and reaches its mouth at Humber Bay on Lake Ontario in the city of Toronto.

Watershed

The Humber watershed is a hydrological feature of south-central Ontario, Canada, principally in north and west Toronto. It has an area of 903 square kilometres (349 sq mi), flowing through numerous physio-graphic regions, including the Oak Ridges Moraine and the Niagara Escarpment.[7] The watershed is bounded on the west by the Credit River, Etobicoke Creek and Mimico Creek watersheds, and on the east by the Garrison Creek, Don River and Rouge River watersheds, all six of which empty into Lake Ontario; on the north by the Nottawasaga River which empties into Lake Huron; and on the northeast by the Holland River, which empties into Lake Simcoe.[2]

Unlike the Don to the east, the Humber remained relatively free from industrialization as Toronto grew. Since the flooding of Hurricane Hazel, it has been largely developed or redeveloped as parkland, with the extensive and important wetlands on its southern end remaining unmolested. Whereas the mouth of the Don is often clogged with flotsam and is obstructed by low bridges, the Humber is navigable and used for recreation and fishing.

Today the majority of the Toronto portion of the Humber is parkland, with paved trails running from the lake shore all the way to the northern border of the city some 30 km away. Trails following the various branches of the river form some 50 km of bicycling trails, much of which are in decent condition. Similar trails on the Don tend to be narrower and in somewhat worse condition, but the complete set of trails is connected along the lake shore, for some 100 km of off-road paved trails.

Tributaries

- Albion Creek - The Albion Creek is a tributary of the West Humber. It flows south-west from east of Bolton, meeting the West Humber from the north, between Islington Avenue and Martin Grove Road. It is approximately 9 km long.

- Berry Creek - Berry Creek originates at Martin Grove Road just north of Rexdale Boulevard. It flows south-east to meet the main Humber from the west, west of the intersection of Albion Road and Weston Road, where Albion Road crosses the Humber. It is about 3.8 km long.

- Black Creek - The Black Creek originates north of Toronto in Vaughan and meanders southerly to meet the lower Humber from the east about 800 m north of Dundas Street, in Lambton Park.

- Centreville Creek

- East Humber - The East Humber flows from north of Toronto, meeting the main branch of the Humber in Woodbridge, just north of Highway 7. Its watershed extends east to Yonge Street and north to King City. Its source is Wilcox Lake and its wetlands east of Yonge Street and the village of Oak Ridges.

- Emery Creek - Emery Creek flows from its source west of Finch Avenue and Weston Road, south to meet the main Humber 500 metres west of Weston Road, about 1 km south of Finch Avenue. It is about 2.4 km long.

- Humber Creek - The Humber Creek runs south east, from its source near Islington Avenue and Dixon Road through residential areas, meeting the lower Humber from the west about 750 metres north of Eglinton Avenue. It is about 3.8 km long.

- King Creek - King Creek is a tributary of the East Humber. It flows southerly from near Highway 27 and 16th Side Road to meet the East Humber south of King Road, east of Nobleton. The settlement of King Creek is located to the east of the confluence.

- Purpleville Creek

- Rainbow Creek

- Salt Creek

- Silver Creek - The Silver Creek runs south-westerly from its source about 300 metres west of Eglinton Avenue and Royal York Road, partly within a golf course, through residential areas to meet the lower Humber from the west about 1.2 km south of Eglinton Avenue. It is about 2 km long.

- West Humber - The West Humber meets the main branch of the Humber east of Albion Road and about 800 metres west of Sheppard Avenue and Weston Road. The West Humber itself has several branches flowing from north-west of Toronto.

Source: Toronto and Region Conservation Authority,[8] The Atlas of Canada.[9]

See also

- Bolton

- Etienne Brule Park

- Etobicoke

- Humber Bay Arch Bridge

- Humber Valley Village

- Lambton Mills

- List of Ontario rivers

- Weston

References

- ↑ "Humber River". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Humber River". The Canadian Heritage Rivers System. 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- 1 2 "Humber River". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2010-02-04. Retrieved 2012-03-15. Shows the course of the river highlighted on a map.

- ↑ Roberts, Wayne (July 11, 2013). "Whose land?". Toronto, ON: Now.

- ↑ http://ontarioroots.com/content/04/04_02/article_008.html

- ↑ "The real story of how Toronto got its name". Natural Resources Canada.

- ↑ "Humber river watershed plan: Pathways to a healthy Humber" (PDF). Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. June 2008. p. iii. ISBN 978-0-9811107-1-4. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ↑ Humber River: State of the Watershed Report – Aquatic System (PDF) (Report). Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. p. 27.

- ↑ "Natural Resources Canada: Toporama". Natural Resources Canada.

Other map sources:

- Map 3 (PDF) (Map). 1 : 700,000. Official road map of Ontario. Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- Restructured municipalities - Ontario map #6 (Map). Restructuring Maps of Ontario. Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. 2006. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Humber River (Ontario). |

- The Humber Watershed at the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority

- Flooding events in Canada - Ontario, an Environment Canada page