House of Zhao

| Zhao | |

|---|---|

| Country | Song Empire (China) |

| Estates | Palaces in Kaifeng and Hanzhou |

| Titles | Emperor of the Song Empire |

| Founded | 960 |

| Founder | Zhao Kuangyin |

| Final ruler | Zhao Bing |

| Deposition | 1279 |

| Ethnicity | Han Chinese |

The House of Zhao (traditional Chinese: 趙; simplified Chinese: 赵; pinyin: Zhào; Wade–Giles: Chao) was the imperial clan of the Song Empire (960–1279) of China.

Family history

Origin

The House of Zhao originated from the Zhao family of Zhuo Commandery (涿郡; Zhuó Jùn),[1] which is located around present-day Zhuozhou, Hebei Province in China. This Zhao family has a long history since the Spring and Autumn period (roughly 771–476 BCE).

The Tianshui Zhao 天水趙氏. The Song dynasty Emperors hailed from the Guandong Zhao while the Longxi Li produced the Tang Emperors.[2]

The founder of the Song Empire, Zhao Kuangyin, was born in a military family. His father, Zhao Hongyin, moved from Zhuo Commandery to Luoyang. Zhao Kuangyin also had an elder brother Zhao Guangji, two younger brothers Zhao Kuangyi and Zhao Guangmei, and two younger sisters.

During the reign of Emperor Zhenzong, the Yellow Emperor was claimed to be as an ancestor of the Song emperors.[3]

Rise of the Zhao family

Zhao Kuangyin started his military career under the Later Han dynasty. However, he quickly changed his stance, and came to serve Chai Rong, an enemy of the Later Han. He also persuaded his father, who was a Later Han general, to serve Chai Rong. This caused the decline and collapse of the Later Han. With Chai Rong's trust, Zhao Kuangyin was assigned to be a guardian for Chai Rong's seven-year-old son, Guo Zongxun, before Chai's death.

However, with great accomplishment, ambition, and followers' loyalties and supports, Zhao Kuangyin eventually replaced Guo Zongxun during a peaceful military coup, and became the emperor of a new dynasty, the Song dynasty. Through years of effort, Zhao Kuangyin conquered other rival states in the south and unified them under his newly established Song Empire. In order to prevent a similar military coup from happening again and to strengthen civilian control over the military, Zhao Kuangyin dismissed his generals and sent them home. This inadvertently resulted in the Song Empire having a weak military later.

Zhao Kuangyin reigned for 17 years and died suddenly and suspiciously in 976 at the age of 49. His younger brother, Zhao Kuangyi (Emperor Taizong) became the new emperor. It was suspected that Zhao Kuangyi murdered his brother for the throne, and did the same to his two nephews to prevent them from seizing the throne. The subsequent emperors – Emperor Zhenzong through Emperor Gaozong – were all descendants of Zhao Kuangyi, until Emperor Gaozong passed the throne to Zhao Shen (a descendant of Zhao Kuangyin), and adopted him as his son.

Decline after the Jingkang Incident

Nevertheless, the Song Empire still thrived under Zhao Kuangyi (Emperor Taizong)'s reign. But the threats of northern nomadic empires, such as the Khitan-led Liao Empire, Jurchen-led Jin Empire and Tangut-led Western Xia still posed threats to the Song Empire. On 20 March 1127, the Song capital, Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng) fell to Jin forces during the Jin–Song Wars. After several days' looting and raping, the Emperors Huizong and Qinzong, along with most of their family members, were captured and taken to the Jin capital, Shangjing, in present-day Harbin. This event is historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Many of these nobles died from illness, hunger, torture and rape during the journey or after arriving in Shangjing. Some of them committed suicide to avoid being humiliated by the Jurchens.[4]

Emperor Huizong's ninth son, Zhao Gou (Emperor Gaozong), escaped from Bianjing and fled to southern China, where he reestablished the Song Empire (as the Southern Song dynasty) with its capital at Lin'an (present-day Hangzhou) and himself as the new emperor. As his only son died prematurely, Emperor Gaozong had to pass his throne to Zhao Shen (Emperor Xiaozong), a descendant of Zhao Kuangyin (Emperor Taizu). The imperial lineage now went back to Zhao Kuangyin's line.

In 1234, the Song Empire allied with the Mongol Empire against the Jin Empire to regain their lost pride in the Jingkang Incident, but the alliance allowed the Mongols to discover Song's military weaknesses. After the fall of the Jin Empire in 1234, the Song–Mongol alliance quickly broke up, and the two empires went to war.

Fall of the Song Empire

On 19 March 1279, the Song chancellor Lu Xiufu committed suicide with the eight-year-old Zhao Bing after the remaining Song forces were completely wiped out by Mongol forces at the Battle of Yamen. The Song Empire ended, and the House of Zhao completely lost control over China. China came under Mongol rule (the Yuan dynasty) for nearly a century before the Han Chinese-led Ming dynasty, founded by the House of Zhu, was established.[5]

Descendants

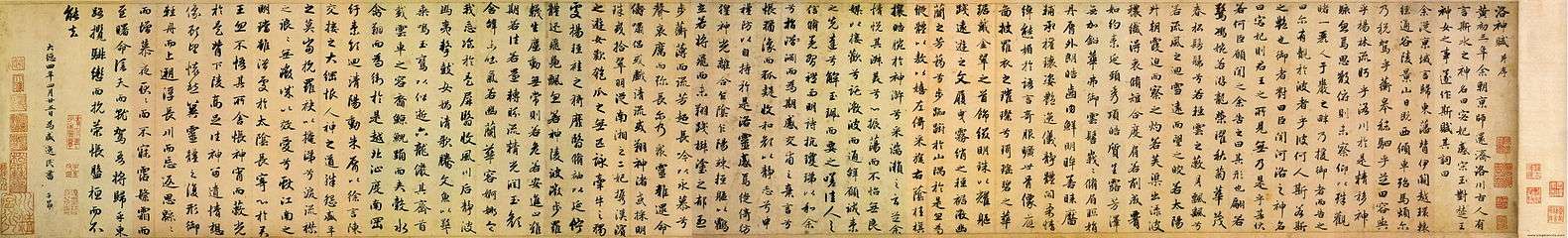

Zhao Mengfu,[6][7] a descendant of the House of Zhao, became a famous painter during the Yuan dynasty. He met the Yuan emperor Kublai Khan on one occasion. He was also the father Zhao Yong and maternal grandfather of Wang Meng, both were also accomplished scholars and painters.

Other descendants of the House of Zhao included Zhao Yiguang (1559-1625), who lived during the Ming dynasty. His wife was Lu Qingzi, who was also an intellectual and member of the scholar-gentry class.[8][9] Zhao patronised his wife's books with his money.[10] Zhao Yiguang and Lu had a son, Zhao Jun, who married Wen Congjian's daughter, who was also from a gentry family and literati who wrote poems.[11]

Two of his works are housed in the Wang Qishu. They were the Jiuhuan Shitu (九圜史圖) and the Liuhe Mantu (六匌曼圖). They were part of the Siku Quanshu.[12]

The Zhao Imperial family survived into the Ming and Qing dynasties.[13][14][15]

Currently the descendants of the Zhao Imperial family are split across more than 20 different branches.[16]

Currently, there are many known members of the House of Zhao living in the Zhao Family Fort (趙家堡) in Zhangpu County, Fujian Province, where they taken up a residence since the Yuan dynasty, and in Hua'an County. There are some members residing in Guangdong Province.

Descendants of the Song emperors live in Chengcun Village near the Wuyi Mountains in Fujian Province.[17]

The surname Zhao was also adopted by the Nong family, who are not related to the House of Zhao.[18][19]

Family tree of emperors

The Generation poem used by the Zhao family was "若夫,元德允克、令德宜崇、師古希孟、時順光宗、良友彥士、登汝必公、不惟世子、與善之從、伯仲叔季、承嗣由同。"[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28] The 42 characters were split into three groups of 14 for the offspring of Song Taizu and his two brothers.[29]

Notable members

- Song dynasty emperors

- Zhao Mengfu, Yuan dynasty artist

- Zhao Yong, artist, Zhao Mengfu's son

- Wang Meng, artist, Zhao Mengfu's maternal grandson

- Zhao Yiguang, Ming dynasty writer, related to Zhao Mengfu

Gallery

-

Emperor Huizong of Song, Ting Qin Tu (Chinese: 聽琴圖, literally "Listening to the Qin"

-

Emperor Huizong of Song (Poem and Calligraphy)

-

Emperor Huizong of Song, Plum and Birds

-

Emperor Huizong of Song, Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers

-

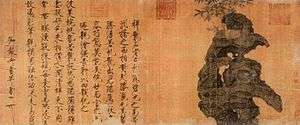

Emperor Huizong of Song, Dragon Stone

-

Emperor Huizong of Song, Cranes 1112

-

Emperor Huizong of Song, Classic Thousand-character Grass script

-

Handscroll%2C_ink_and_colors_on_paper%2C_28.4_x_93.2_cm_National_Palace_Museum%2C_Taipei.jpg)

Autumn colors on the Qiao and Hua mountains, by Zhao Mengfu

-

A Man and His Horse in the Wind, by Zhao Mengfu

-

Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees, by Zhao Mengfu

-

A Sheep and Goat, by Zhao Mengfu

-

Old Tree and Horses, by Zhao Mengfu

-

Zhao Mengfu writes the Tale of the Goddess of Luo River.

See also

References

- ↑ 陳邦瞻【宋史紀事本末】卷一

- ↑ Revue bibliographique de sinologie. Éditions de l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales. 1960. p. 88.

- ↑ Patricia Buckley Ebrey (2003). Women and the family in Chinese history. Psychology Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-415-28823-1.

- ↑ "Moaning Words" 宋人無名氏【呻吟語】

- ↑ Rossabi 1988, p. 76

- ↑ http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp110_wuzong_emperor.pdf p. 15.

- ↑ John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- ↑ Ellen Widmer; Kang-i Sun Chang (1997). Ellen Widmer; Kang-i Sun Chang, eds. Writing women in late imperial China (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-8047-2872-0.

Lu Qingzi married a man who led an equally idyllic life, Zhao Yiguang (1559-1625 ), a descendant of the Song imperial family. Zhao fancied himself a recluse but often busied himself entertaining powerful and learned friends.

- ↑ Ellen Widmer, Kang-i Sun Chang (1997). Ellen Widmer, Kang-i Sun Chang, ed. Writing women in late imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-8047-2872-0.

At age 15 sui, she married a literatus, Zhao Yiguang (zi Fanfu, 1559-1625) with whom she lived in seclusion in Hanshan.

- ↑ Dorothy Ko (1994). Teachers of the inner chambers: women and culture in seventeenth-century China. Stanford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 0-8047-2359-1.

- ↑ Marsha Smith Weidner (1988). Marsha Smith Weidner, Indianapolis Museum of Art, ed. Views from Jade Terrace: Chinese women artists, 1300-1912. Indianapolis Museum of Art. p. 31. ISBN 0-8478-1003-8.

She married ZhaoJun, scion of an old Suzhou family, which traced its ancestry back to the imperial family of the Song dynasty and which counted among its sons the famous official and artist Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322). Zhao Jun's father was the recluse-scholar Zhao Yiguang (1559- 1625), and his mother was a daughter of Lu Shidao (1511-74), another Suzhou literatus. Zhao Jun studied the classics with Wen Congjian; thus a more permanent liaison between the two families was perhaps inevitable.

- ↑ Florence Bretelle-Establet (2010). Florence Bretelle-Establet, ed. Looking at it from Asia: the processes that shaped the sources of history of science. Volume 265 of Boston studies in the philosophy of science (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 90-481-3675-X.

- ↑ John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- ↑ John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- ↑ John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 247–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- ↑ John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 272–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- ↑ http://www.china.org.cn/english/culture/50676.htm

- ↑ Katherine Palmer Kaup (2000). Creating the Zhuang: Ethnic Politics in China. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-55587-886-3.

- ↑ James A. Anderson (20 December 2012). The Rebel Den of Nung Tri Cao: loyalty and identity along the Sino-Vietnamese frontier. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80077-6.

- ↑ http://blog.sina.com.cn/zjf895

- ↑ 梁永樂、趙公梃 (1 July 2014). 八爪魚家長──孩子愛玩不是罪. 明窗. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-988-8287-38-3.

- ↑ http://gzdaily.dayoo.com/html/2015-07/26/content_2976755.htm

- ↑ http://wiki.zupulu.com/topic.php?action=resumesview&topicid=15469

- ↑ https://book.douban.com/reading/10139098/

- ↑ http://tieba.baidu.com/p/2257773932?see_lz=1

- ↑ http://blog.renren.com/share/259684396/8724489897

- ↑ http://guangdong.kaiwind.com/yyfh/201506/02/t20150602_2547276.shtml

- ↑ John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- ↑ Thomas H. C. Lee (January 2004). The New and the Multiple: Sung Senses of the Past. Chinese University Press. pp. 357–. ISBN 978-962-996-096-4.